Using Ancient Near Eastern Parallels in Old Testament Study

003

Isaiah 40:18 asks: “To whom can you liken El? What likeness can you compare him to?” (Similar questions are posed in Isaiah 40:25 and 46:5.) The questions are rhetorical. The prophet’s point is that God is incomparable. As the verses following Isaiah 40:18 explain, it is absurd to make an image of God. Many Old Testament passages echo these sentiments (see Exodus 8:10; 15:11; Deuteronomy 33:26; 1 Samuel 2:2; 2 Samuel 7:22; 1 Kings 8:23; Micah 7:18; Psalm 89:7 [6 in English]; 1 Chronicles 17:20).

But if there is nothing to which God can be compared, how can a person know anything about Him or worship Him? Even the poet who penned these verses compared God’s attributed to what his readers could conceive and understand: “He will feed his flock like a shepherd” (Isaiah 40:11).

What cannot be compared cannot be understood. Human experience is a matter of image-making and comparison—from the most sophisticated scientific to the most elemental physical response to the world. The question is: What kind of comparisons will give us the most accurate understanding of our images?

The data for comparison—either positive or negative—constitute “parallels.” In the broadest sense, parallels are simply comparative material which helps to better understand the Old Testament.

There are two ways to use parallels in Old Testament study. The folklorist Theodore H. Gaster exemplifies the first. In Myth, Legend, and Custom in the Old Testament, Gaster collects parallels from any place and any time. He is not concerned with whether there were any direct or even indirect cultural contacts or borrowings between the Israelites and the people who supply the parallel. He will draw as easily on a contemporary culture as on an ancient one for comparative purposes. But Gaster is simply a collector. He attempts to illustrate patterns of thought and feeling. His parallels show the varied expressions of basic ideas. He expects the cumulative evidence to unveil the true, or original, significance of things which are inevitably distorted in any one historical tradition. In this way he hopes to interpret Old Testament passages in the light of the parallels he assembles. To those who suggest that this path is frivolous, he replies that the diversity of his comparisons enhances, rather than diminishes, their significance.

Another approach looks for comparisons connected by a historical thread. The unique nature and purpose of a text appears in its context. Its uniqueness consists of the differing ways it employs traditions it shares with neighboring texts or in original contributions to these traditions. The study of parallels emphasizes the individuality of the text by exploring its differences from and similarities to comparable texts.

Most contemporary scholars agree that parallels must be studied. The problem is how and what to compare. Some comparisons tell us something about the Old Testament. Others do not; they have no generalizable significance. In his 1961 Presidential Address to the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Samuel Sandmel warned his audience of a dangerous scholarly disease which he called “Parallelomania.” Sandmel described parallelomania as “that extravagance among scholars which first overdoes the supposed similarity in passages and then proceeds to describe source and derivation as if implying literary connection flowing in an inevitable or predetermined direction.”

Sandmel’s purpose was not to discourage the study of parallels, but to stem the exaggerated claims being made about supposed parallels. Taken out of context, two passages may sound the same. But their contexts may 004show that they are more different than alike. Excerpts alone can be very dangerous.

For example, the Ugaritic phrase ymlk ‘ttr ‘rz (49 1:27)a looks exactly parallel to the Hebrew phrase ymlk yhwh (Psalm 146:10). The first word of each phrase is the same verb, followed by a divine name which is the subject of the verb. But the immediate context of the Hebrew expression shows that it is a proclamation: “Yahweh will reign.” The Ugaritic phrase is a proposal by Atrt to El to make ‘Attr king after Baal’s death: “Let ‘Attr the terrible reign.” Different situations lie behind the two phrases, and they are not parallel at all.

Does this mean that correspondence in wording is unimportant? No, just that similar language does not necessarily indicate similar meaning. Substance determined by context is the key.

But the search for context must go beyond the immediate passage, because the meaning of the immediate passage depends on the whole fabric of thought which forms the context of a particular text.

Unfortunately, the ancient world has not passed this fabric on to us whole. The materials are accidental and fragmentary. The ancients did not record all the vital information. In the course of transmission much was perverted or lost. We have not yet uncovered much that is available. Indeed, what we don’t know about the context of the ancient world far exceeds what we do know.

Given these limitations, the scholar must cast a wide net in the quest for parallels.

In a recent review of the first volume of Ras Shamra Parallels: The Texts from Ugarit and the Hebrew Bible,b edited by Loren R. Fisher, Johannes C. De Moor accused the contributors of raising “The Spectre of Pan-Ugaritism.”c De Moor objected because the comparisons were limited to Ugarit. The search for common elements should take into account all the cultural remains of the ancient Near East, he said. 005The Ugaritic-Hebrew limitation creates “the false impression that there exists a rather special kind of relationship between Hebrew and Ugaritic.” Without the context of the entire ancient Near East, the indebtedness of one culture to another cannot be understood.

Second, said De Moor, similarities alone do not show much unless the differences too are explained; the differences illuminate the distinctive elements of Ugaritic or Israelite religion and culture.

Sandmel spoke of “significant” and “merely routine” parallels. The latter include parallels which are insignificant because their absence would be more surprising than their presence. Related populations can be expected to share certain features. Some characteristics appear in all populations. According to De Moor, Ras Shamra Parallels fails to make the distinction between routine and significant parallels in Ugaritic-Hebrew relationships because it excludes vital data from other ancient Near Eastern cultures.

That comparative studies must consider context and ultimately seek to discover the individuality of each tradition is of course true. Indeed, Loren Fisher stressed this himself in his introduction to Ras Shamra Parallels. He pointed out that the identification of the common not only certifies the unique aspects of one culture—it provides safeguards against an unrealistic view of a single tradition. For instance, many scholars had thought that Israelite ritual developed in a unilinear sequence from simple to complex. In this schema, ritual texts with exact dates and great detail should be late. The texts from Ugarit show that the presence or absence of exact dates and myriad details depends on the type of ritual text, not the age of the text. The wider context unveils the possibilities available to Israelite ritual from its beginnings and provides the basis for a sounder description of its development.

Fisher also stressed that while Ugaritic materials are important to Biblical studies, this same kind of study should be undertaken for other groups of texts as well. But De Moor’s criticism notwithstanding, it cannot all be done at once. The Ras Shamra Parallels are expected to fill three large volumes—and then still be incomplete! When similar studies are made of all the traditions of the ancient Near East, scholarship will be closer to the far-reaching conclusions that De Moor demands immediately.

The scholar is always in the midst of a process, drawing tentative conclusions both about the common and the unique elements of cultures being studied. Because the Ugaritic materials are so important to the study of the Old Testament, they do create a danger that other non-Israelite contexts will be ignored—the danger of “pan-Ugaritism,” against which De Moor warned.

Ugaritic scholars would not be the first to fall into this trap. From its beginnings in the mid-nineteenth century, Assyriology scanned its own texts for contributions to Old Testament interpretation. Hugo Winkler, the great German Assyriologist who early translated the Armarna letters and the Code of Hammurapi, turned some Assyriologists in the direction of “pan-Babylonianism” with his view that the fundamental outlook for the Israelites (as well as other ancient Near Eastern peoples) originated in Babylon and from there spread throughout the whole world.

On January 13, 1902, Friedrich Delitzsch whom many regard as the founder of Assyrian philology, delivered his notorious address “Babel and Bibel” before the German Oriental Society in Berlin. Delitzsch proposed that a philosophy of life satisfactory to the head as well as the heart could be found only by combining the best of Old Testament and Mesopotamian literature: Babel and Bible. During the next twenty years Delitzsch and his disciples continued to radicalize this position.

Delitzsch pointed out that prior to the opening of the pyramids and the excavation of the Assyrian palaces in Mesopotamia, the Christian church had accepted the Old Testament as a supernatural document reflecting the beginning of history. But times have changed, he said. The people of Israel and their writings turned out to be only younger 006cousins of the cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeological discoveries had removed the halo of timelessness and absoluteness from the Old Testament. The loss of the halo took away its authority. The treasures preserved in the Old Testament really derive from Mesopotamia, not Israel.

According to this view, Babylonian influence saturated the culture of Palestine giving the Israelites who settled there a literature (especially the Babylonian creation and flood stories), a language (Babylonian), a system of weights and measures, a system of coinage, laws, and the Sabbath. In every case examined by Delitzsch and his pan-Babylonians, the material from the East was the enlightening element; the Old Testament shone only in the reflected glow of the foreign texts.

Waves of protest eventually overwhelmed Delitzsch’s position. Critics of his “Babel and Bibel” address responded that the differences between Babel and Bible overshadowed the similarities. Delitzsch never retreated from his original pan-Babylonianism. In 1921 his work culminated in a book entitled Die grosse Tauschung—“The Big Fake.” There Delitzsch stated that the Old Testament had no religious meaning for modern man, especially for Christians, Judaism and Christianity had nothing to do with one another. Indeed, Judaism was one of the heathen religions. With this, Delitzsch’s anti-Semitism surfaced. The ultimate goal of his pan-Babylonianism was not so much the glorification of Mesopotamian traditions as the vilification of the Old Testament and Judaism.

Fortunately, this kind of thinking has no place in the current debate about the importance and direction of the study of Ugaritic parallels. Pan-Babylonianism was, in fact, an aberration in ancient Near Eastern scholarship. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the Babylonian literature of Israel’s neighbors significantly altered our understanding of the Old Testament.

Between 1850 and 1900, and especially after 1880, archaeological discoveries of important groups of ancient Near Eastern texts slowly turned Old Testament studies toward an examination of Israel’s environs. Historical and religious documents found in Egypt and Mesopotamia yielded new knowledge of Israel’s historical and cultural connections with its neighbors; this new knowledge shattered the romantic-idealistic conceptions of Israel’s primitive-natural-heathen-childish beginnings. Israel began late in the history of human civilization—not in its primitive stages. The notion of Israel’s simple origins as proposed by such 007scholars as Julius Wellhausend could no longer stand. The time when modern Arabic nomadism could provide the model for Israel’s early social organization had ended. To a gifted scholar like Wellhausen at home in classical Arabic, the new discoveries remained a foreign world which he could not enter. The Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts thrust Israel into a real world. Specific parallels, grounded on historical and cultural connections, replaced abstract speculation.

Palestinian archaeology came of age at the close of the nineteenth century. The Englishman William Flinders Petrie initiated the systematic investigation of the land of Israel in 1890 with his stratigraphic excavation of Tell el-Hesi. In the dating of pottery he found the basis for historical differentiation between recognizable levels of a site. The ability to make historical discriminations gave archaeology access to the culture of Palestine before the Israelite period. Previously, scholars could only speculate about this culture on the basis of Old Testament allusions to it. After 1900, Palestinian archaeology began to fill out the picture of the culture and religion of the ancient world.

Most of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts discovered in the 19th century were relatively remote from the Israelites in time and culture, but the texts found at Tell el Amarna in upper Egypt in 1887/88 provided direct access to the Palestinian situation shortly before the Israelite period. The Amarna tablets consisted in large part of diplomatic letters from petty rulers in Syria and Palestine to their Egyptian overlords in the 14th century B.C. They showed that politically Egypt controlled Syria and Palestine around 1400 B.C., but the star of the Pharaohs was sinking. They were powerless to bring order during a desperate period in Palestine. A feud of all against all characterized the political and social scene. Not only were the city-rulers at odds with one another, but lawless segments of society plundered and robbed the rest.

The Amarna letters indicated another influence operative in Palestine. They were written in Babylonian signs and language—a sort of cuneiform “pigeon-Babylonian” to be sure, but recognizable Babylonian. This 008suggested a strong Mesopotamian cultural influence in Syria-Palestine prior to 1400 B.C.

Old Testament research discovered in the Amarna evidence a new, two-sided orientation: Israel caught between the two great cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt. This initial picture, however, proved to be too simple. Other great powers also exerted periodic influence over Israel. But the new perception of ancient Near Eastern history provided by the Amarna letters and other texts from Mesopotamia as well as Egypt posed an entirely new problem of textual comparison for Old Testament scholarship.

The parallels appeared. The supposed originality of the Old Testament creation story in Genesis 1 fell before the parallels discovered in the Babylonian creation story, Enuma Elish. The eleventh tablet of the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic told of a great flood similar to that recounted in Genesis. The Code of Hammurapi proved that Israel’s “law” came not as an original revelation from God, but had appropriated some elements of the highly developed legal traditions of the ancient Near East.

Understandably, the similarities dominated the attention of the first comparative scholars. But soon other scholars highlighted the differences. Still others, like the pan-Babylonians, attempted to build artificial bridges between the Old Testament and the ancient Near East.

The ultimate goal of comparative studies is to understand the unique contribution of a single tradition.

Archaeology has now thrust the world of the Old Testament into the historical past, and there can be no retreat from the study of parallels. The Old Testament can no longer be understood in isolation. Old Testament research is inevitably historical-critical research. This is comparative research.

Strictly speaking, the term “parallel” does not refer to things which are identical. Parallel lines never intersect. Practically 009speaking, however, identities form an important aspect of comparative studies, especially at the level of individual words. Only by comparison did Ugaritic tb, “sweet,” reveal that Hebrew tob sometimes means “sweet” instead of the usual “good” (see Song of Songs 1:2). From the fact that Akkadian Gubla, Ugaritic Gbl, and Hebrew Gabal all designate the Phoenician city we call Byblos, we can appreciate the overlapping of geographic horizons in different bodies of literature, the existence of places before the Israelite period, and earlier pronunciations of Hebrew place names. Differences as well as similarities appear.

Beyond the comparison of words, other more inclusive categories of comparison—like literary phrases—reveal other kinds of parallels. For example, Ugaritic text 68:8–9 reads:

Now, your enemies, O Baal,

Now, your enemies you will smite,

Now, you will vanquish your foes.

Psalm 92:10 (9 in English) reads:

For now your enemies, Yahweh,

For now your enemies shall perish,

All evildoers shall be scattered.

The two texts show the same verse structure, and their content is strikingly similar, implying some literary contact. But there are difference, too. The Ugaritic text, refers to a definite mythological foe, Yamm, while in the psalm Yahweh’s enemies are also the psalmist’s. In the Ugaritic text, Baal is to strike the enemy; in the psalm, Yahweh’s enemies simply perish. The context is also different: Baal’s destruction of his enemies forms a prelude to his enthronement; the Ugaritic verse occurs in a mythological narrative in which Baal destroys an enemy to become the head of the pantheon. The psalm is a hymn of thanksgiving, sung to music in the cult (v. 3). The psalm appears to transpose a known mythological motif into a glorification of Yahweh as the victor over the power of evil and the enemies of His people. The parallel clarifies the background and intention of the psalm. As shown, v. 10 has a mythological background. That the psalmist uses a well-known expression in an entirely different meaning suggests a rejection of Baal mythology (where the enemy is a god) in favor of a different concept of the deity (Yahweh’s story relates to people, not other deities).

Ancient Near Eastern social customs often 010highlight the intention or practice recorded in the Old Testament. Ugaritic texts (2 Aqht I:27, 45; II:16e) tell is that the ideal son should make sure that a stelef is erected to the family deity in the sanctuary—as a mark of filial piety. This practice gives substance to 2 Samuel 18:18 where Absalom himself inexplicably erects a stele, saying: “I have no son to keep my name in remembrance.” Since Absalom was not childless (2 Samuel 14:27), it is particularly poignant that he had to erect the stele himself. No Old Testament passage specifically attributes the erection of a stele to filial piety, although the background stands out clearly with the help of the Ugaritic parallel.

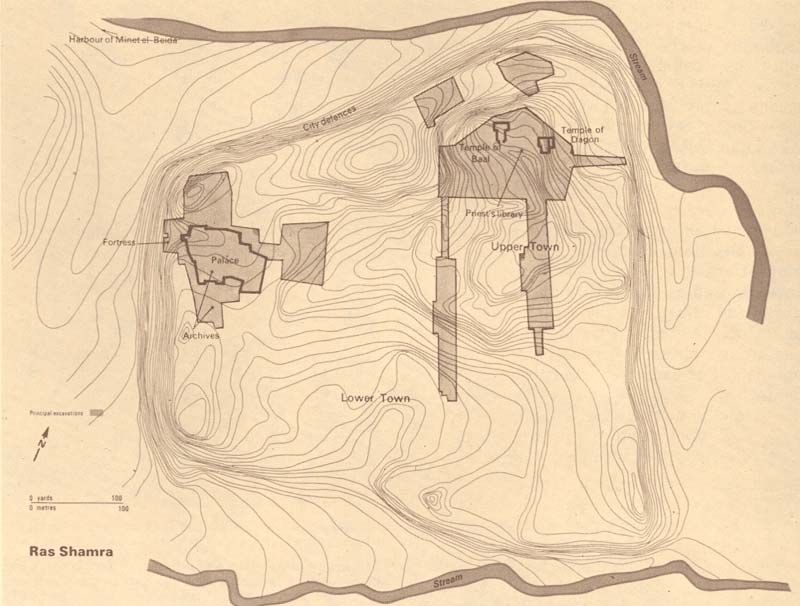

I have taken these examples from Ugarit partly because I know it best, and partly because, despite De Moor, a special kind of relationship does exist between the Ugaritic literature and the Old Testament. History and geography determined it. Ugarit formed part of an East Mediterranean geographical and cultural continuum with Palestine (see map). The Ugaritic period was historically close to that of Israel.g Of course, there are significant differences, too. For example, Ugarit was a port city—a trade center—unlike Jerusalem. And there is a time and geographical difference as well. Ugaritic materials are not direct evidence for the Canaanite society which the Hebrews entered, but they are the best evidence yet discovered. Although Ugarit entered its final days as the Israelite period began,h cultural and religious realities reflected in the Ugaritic texts continued to flourish in places like Jerusalem.

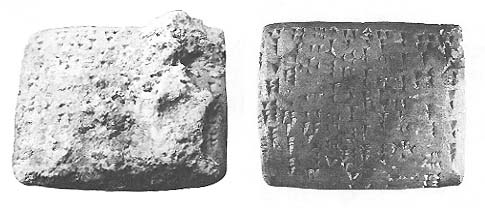

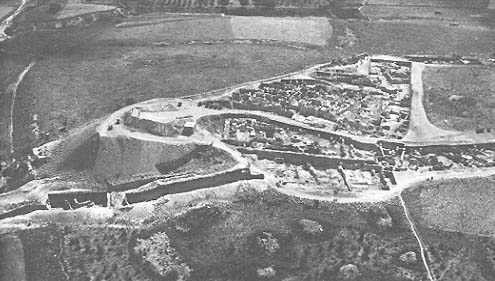

011Accident of discovery also determined the special relationship between Ugaritic literature and the Old Testament. In the first expedition to Ras Shamra in 1929, excavation director C. F. A. Schaeffer found in the northeast part of the tell temples of Baal and Dagan, and a great library. Texts from this library contain cultic and mythological rites and epics. Deities known only from the Old Testament as Yahweh’s enemies came to life: deities like Baal and Asherah. In the expedition of 1937, Schaeffer and his team of archaeologists uncovered a stables-arsenal archives-palace complex in the northwest section of the tell. Official documents from the royal archives told of the inner workings of the government and society. The Ugaritic economic system gradually took shape as the texts were read. The finds included metal and stone statues, reliefs of gods and goddesses, and an abundance of commodities. And all Ras Shamra’s treasures have not yet been excavated. Work on the tell will no doubt continue.

At the turn of the century the world of Old Testament scholarship buzzed with excitement over the finds from Mesopotamia and Egypt. No one then suspected that one day archaeology would produce such close and surprising connections to the world of Israel as the tablets from Ugarit. Innumerable threads tie the Old Testament to its milieu. The study of parallels places the Old Testament in an authentic context. We can no longer view the Old Testament as a miraculous document dropped by God from heaven. That a real people living in a real world developed an understanding of God that stands apart from, yet is connected to, the rest of that world—this is a genuine miracle.

Isaiah 40:18 asks: “To whom can you liken El? What likeness can you compare him to?” (Similar questions are posed in Isaiah 40:25 and 46:5.) The questions are rhetorical. The prophet’s point is that God is incomparable. As the verses following Isaiah 40:18 explain, it is absurd to make an image of God. Many Old Testament passages echo these sentiments (see Exodus 8:10; 15:11; Deuteronomy 33:26; 1 Samuel 2:2; 2 Samuel 7:22; 1 Kings 8:23; Micah 7:18; Psalm 89:7 [6 in English]; 1 Chronicles 17:20). But if there is nothing to which God can be compared, how can a […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Several systems have been devised for citing Ugaritic texts. The system I have used is that of Cyrus H. Gordon Ugaritic Textbook (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1965). The citation refers to text 49, column 1, line 27.

Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1972. Ras Shamra is the modern name of the site; Ugarit the ancient name.

Julius Wellhausen is widely known in connection with the so-called documentary hypothesis, according to which the Pentateuch is composed of separate strands—J (the Yahwist), E (the Elohist), P (the Priestly Code); and D (the Deuteronomist)—, which were later combined by a redactor(s). Wellhausen’s contribution to the documentary hypothesis grew out of his effort to relate the literature of the Old Testament to the actual history of the Israelites.

Some larger texts, like this one, have names. Aqht is the hero of the text. The “2” before the name indicates the second tablet.

The Ugaritic tablets date from the 14th–13th centuries, although the myths they contain probably reflect much older traditions and language. The Exodus from Egypt is generally considered to have occurred in the latter half of the 13th century.