In the waning years of the first century A.D., one of the six Vestal virgins who guarded Rome’s sacred flame was accused of breaking her vow of chastity. Sentenced to death by the emperor Domitian (81–96 A.D.), she was dragged to an underground chamber just inside the city walls and buried alive. Her alleged lovers were hung upon forked sticks and beaten to death in the Forum.

Soon after the executions, the author and lawyer Pliny the Younger (61–112 A.D.) wrote to his friend Cornelius Minicianus that the accused Vestal, a senior priestess named Cornelia, was probably innocent (Epistle 4.11). She had been executed merely because the emperor wished to demonstrate his rigorous justice, however tyrannical. Punishing a Vestal signaled that he would maintain the purity and prosperity of Rome.

As Domitian’s use of Cornelia’s death shows, the Vestal virgins were much more than just a group of cloistered young priestesses. They were, in fact, key political players, who personally embodied the health and well-being of the Roman state. In their role as guardians of the city’s sacred flame, the Vestals enjoyed greater political influence (and endured harsher scrutiny) than any other group of women in the ancient world.

In myths about the founding of Rome, the cult of the Vestals can be traced back to the eighth century B.C., when an Etruscan king, Numa Pompilius, built a temple to the hearth goddess Vesta (Hestia) in the area that would later become the Roman Forum. Numa paid homage to the goddess whose priestess was the unwitting mother of Rome’s founder: The Vestal virgin Rhea Silvia gave birth to Romulus after being raped by Mars, the god of war. In fact, archaeological evidence shows a cult of Vesta or activity by the Vestals in the Forum by the sixth century B.C.1

Traditionally, there were six Vestals who served the cult. They took turns caring for Vesta’s flame so that the temple had one priestess in attendance at all times. Each new Vestal was carefully chosen in a rigorous process of selection: She had to be a young virgin (between the ages of 6 and 10), perfect in body and the daughter of a traditional, intact Roman family. Once she was accepted into the cult, the new Vestal was obliged to spend 30 years in Vesta’s service: 10 years as an apprentice learning her ritual duties, 10 years performing her duties and a final 10 years training new Vestals.

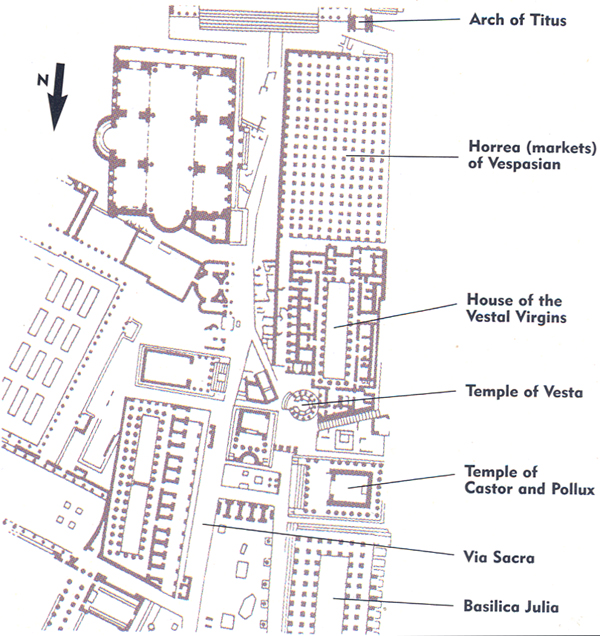

During their tenure with the cult, the Vestals lived next door to the temple, coming and going as their duties dictated. Under the direction of the city’s chief priest, the Pontifex Maximus, they were expected to officiate at various ceremonies throughout the Roman calendar year, including the Lupercalia (an annual fertility festival) and the Parilia (the annual celebration of the founding of Rome).

But the Vestals’ most important responsibility was the protection of the city’s sacred flame. Allowing the flame in the temple of Vesta to go out was a serious offense because it suggested that the goddess had withdrawn her protection from the city. Vestals who were on duty when the flame died were beaten, even when the extinction of the fire was recognized as an accident and not an explicit warning from the goddess.

After her duty to maintain the sacred flame, the Vestal’s highest obligation was to maintain her chastity.2 The priestesses were not cloistered or cut off from human contact; in fact, they were the most publicly visible women in Rome. Although the Vestals served in Rome for at least a thousand years, we know of fewer than ten convictions for unchastity. Moreover, each of these trials came at a time when the state of Rome was under military or political attack—which suggests that the accused Vestals may have been used as scapegoats to ward off disaster from the state.3

Throughout Rome’s history, the sexual purity of the Vestals was closely linked to the health and well-being of the state. When Vestals were inducted into the cult, they were transferred from the authority of their fathers to the authority of the state, becoming daughters of the state. A sexual relationship between a citizen of Rome and a Vestal was therefore considered an act of incest (incestum), constituting both a violation of a social taboo and an act of treason against the city.4

Not surprisingly, Roman authors were fascinated by the trials of the Vestals, and several are recorded in careful detail. The execution of Cornelia was a scandal in its day. The priestess was tried in absentia and never given an opportunity to confront her accusers (most of whom appear to have been bribed or bullied into confessing by Emperor Domitian). Pliny tells us that at least one of her alleged accomplices, the Roman knight Celer, insisted on his ignorance of the crime and the illegal nature of his punishment.

After her conviction, Cornelia was led through the streets of Rome, protesting her innocence and asking how Domitian could suspect her of being unchaste when she had presided over the sacred rituals that accompanied his conquests and triumphs. The emperor’s own successes should have been sufficient proof of her purity and faithfulness.

As she walked down the stairs to her tomb, her robes caught on a step and she stooped to free herself. When her executioner reached out to assist her, Cornelia shuddered and withdrew from his touch in disgust, as if in a last proof of her chastity (Pliny, Epistle 4.11). The Vestal was then walled up alive with a token supply of food and left to die.a

Such unhappy endings, however, were not the rule. Most Vestals appear to have lived out their lives in contented service to the goddess. Despite the fact that all Vestals were free to leave the order and marry after their required 30 years of service, there is no recorded case of a Vestal marrying, and few are known to have retired. When one considers the substantial personal privileges that the Vestals enjoyed, their loyalty to the goddess is understandable.

In general, the political powers of women in ancient Rome were extremely limited: They were not allowed to vote, and they had no direct say in the policies of the state. They possessed little control over their persons, property and children, and they were kept under the supervision of a male relative—father, husband or guardian—throughout their lives. Wealthy Roman noblewomen were not even permitted to leave their houses unattended.

Only the Vestals, with their unique duties and privileges, stood apart. Upon joining the priesthood, they were emancipated from male control; they had the ability to inherit wealth, engage in business dealings, write wills and dispose of their property as they wished. Because they were the quintessential symbols of purity in the state, the Vestals were also permitted to testify in court without taking the traditional oath of honesty. And apparently they did testify—quite frequently. They became the guardians of wills and other important documents, guaranteeing that the documents were authentic and free from tampering.

Since it was customary to make the Vestal who secured a will a beneficiary of that document, some Vestals amassed very substantial fortunes, which they invested or bequeathed as they saw fit. The attraction of the priesthood simply from an economic standpoint was enormous, and indeed we hear of dynasties of Vestals—several generations of aunts and nieces—serving together in the cult.

The Vestals’ most important political privilege, however, was the right to pardon. When encountering a convicted criminal on the way to execution, the Vestals had the ability to absolve him of his crime and prevent his punishment. According to tradition, such a meeting had to be accidental in order to preserve the idea that the criminal’s pardon came at the hands of the gods. But the Vestals also had the power to beg for clemency more directly, by acting as intercessors for accused parties before the city magistrates or even before the emperor. The Vestals’ intercession appears to have been a powerful force. Throughout Rome’s history, numerous leaders sought to connect themselves to the Vestals’ clemency in the hopes of gaining popularity for their regimes.

The Vestals’ privileges and powers, however, were by no means static or unchanging. They developed and altered as the political and social climate of Rome changed.

In the early Republican period (fifth to third centuries B.C.), the Vestals were almost always depicted as victims. Ancient texts from this period mention them mostly in reference to their chastity trials. Not until the second century B.C., when Rome had conquered most of the Mediterranean, do the Vestals begin to appear as historical actors in their own right.

In 143 B.C., the Vestal Claudia assisted her brother or father (the sources vary on his identity but agree that he was a consul) by riding with him in his chariot as he made his triumphal entry into Rome after a military victory (Suetonius, Tiberius 2.4; Cicero, Pro Caelio 34). By doing this, she was defying a decision by the tribune of the people (one of the most powerful officers of the state), who had vetoed her relative’s request for a triumph. Apparently, at least in this case, the Vestals possessed a power superior even to that of the tribunes. At the very least, the sacred inviolability of a Vestal’s person made any attempts to stop or restrain her a crime of impiety. Claudia used her position to sanction a consul’s political celebration.

In the first century B.C., as Rome was torn asunder by brutal civil wars, the Vestals began to intercede in affairs of state with increasing frequency. When the dictator Sulla (138–78 B.C.) was sentencing his political opponents to death and seizing their property, a young Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.) was included on his list of victims; but the Vestals intervened on Caesar’s behalf and gained Sulla’s pardon (Suetonius, Julius Caesar 1.2).

Not surprisingly, when Caesar ascended to the position of Pontifex Maximus in 63 B.C., the Vestals attained a new degree of prominence. He renovated the house of the Vestals and placed his will—an object he knew would be contentious—in the hands of the head Vestal six months before his assassination in 44 B.C. (Suetonius, Julius Caesar 83).

Under the terms of his will, Caesar’s nephew Octavian (later Augustus [63 B.C.–14 A.D.]) was declared his adopted son and heir. Only 18 years old at the time of his uncle’s death, Octavian never forgot the debt he owed the Vestals, who had protected his legacy. In 42 B.C. he granted each of the Vestals the right to a lictor, a kind of government bodyguard cum personal attendant. Lictors traditionally preceded the two chief officials of the Roman state, clearing the way before them, announcing their presence and asserting the officials’ power to judge and condemn with a display of fasces (bundles of rods and axes symbolizing the authority to beat and behead). Granting the Vestals their own lictors suggested that they, too, were among the most important state officials.

As tensions built between Octavian and his chief political rival, Mark Antony, the Vestals continued to play an important role, often serving as guarantors of agreements of good faith and protectors of the innocent. In 41 B.C., when members of the Roman army forced Octavian and Antony to set aside their differences temporarily and draft a treaty of reconciliation, the Vestals were made the official guardians of their agreement. Two years later, after negotiating a difficult peace treaty with the pirate Sextus Pompey (the son of Pompey the Great), Antony and Octavian made a great show of having the document deposited with the Vestal virgins in Rome as a sign of the sacred inviolability of the accord (Cassius Dio 48.37.1).b The very next year, when the terms of the treaty were about to be violated, Octavian retrieved the document from the Vestals to display its conditions publicly.

After losing the battle of Actium to Octavian in 31 B.C., Mark Antony committed suicide, leaving Octavian without significant opposition. Octavian was now in control of all of Rome’s massive legions and in possession of enormous wealth (he took Egypt as his private property). When he returned to Rome in triumph, the senate—afraid of his power but glad for peace—voted to have him greeted by the Vestals as he stepped onto the shores of Italy. The senators also decreed that the condemned criminals throughout Italy who were to be executed on that day should receive amnesty—thus pointing out the value of clemency to the new regime.5

Following Octavian’s return, he was given the title “Augustus,” along with all the important powers of the state. As the first de facto emperor of Rome, Augustus continued to honor the Vestals. When he became Pontifex Maximus in 12 B.C., he gave the Vestals the public house traditionally inhabited by the chief priest. This was then incorporated into the Vestals’ own dwelling. With this addition, the house of the Vestals became one of the major public buildings in the city; it was apparently open to visitors, worshipers and public officials. Only the actual private chambers of the Vestals and the interior of the temple of Vesta were off-limits to the public.

With the participation of the Vestals, Augustus also dedicated a new shrine to Vesta in his own house on the Palatine Hill. Two sculptured reliefs illustrating the event have survived; both were found outside Rome, suggesting that the dedication was widely publicized. Augustus also included the Vestals in all important dedications and ceremonies. Their role in Rome’s new era of peace is commemorated on the great Augustan Altar of Peace.

In his continuing quest for legitimacy, Augustus called on the Vestals to play an increasingly prominent role. They received public honors and sat in especially desirable seats in the amphitheater for gladiatorial games and beast hunts. This honor was carefully chosen: During these spectacles, convicted criminals were executed in full view of the audience. Those who were killed had committed what Romans believed to be the worst sorts of crimes: theft from a temple, armed robbery, burglary at night, arson and the like. Their deaths represented the return of social order, and the Vestals’ willingness to withhold clemency and to witness the executions helped give divine sanction to the emperor’s harsh justice.

Augustus also changed the rules regarding membership in the cult. In the Republic, the sacred virgins were drawn at first from aristocratic families and later from the Roman citizen body as a whole, but as the Vestal cult became more closely associated with the emperor, fewer and fewer noble families volunteered their daughters for service. Augustus’s ongoing involvement with the cult may have tainted it with the politics of the civil war. Some old, established families were probably put off by the Vestals’ growing public role, which did not fit the traditional cloistered image of ideal womanhood that the elites espoused (though seldom practiced).

The entrenched nobility may also have resented Augustus’s attempts to reach out to populations that had not previously held power, such as provincial elites and businessmen (often freed slaves). When an opening in the cult occurred in 5 A.D., Augustus allowed the daughters of freedmen to apply for selection.

Augustus left his will, his records concerning the state of the empire’s treasury and military, and his summary of the achievements of his reign under the guardianship of the Vestals. When his stepson, Tiberius, assumed power in 14 A.D., all went smoothly.

Subsequent Roman emperors continued to ally their families with the Vestal cult and to offer the Vestals new honors and financial support. Tiberius (14–37 A.D.) left legacies to the Vestals in his will. Caligula (37–41 A.D.) granted to his sisters and grandmother all the privileges that the Vestals held. When the emperor Claudius (41–54 A.D.) established the cult of Livia (Augustus’s wife and Claudius’s grandmother), he decreed that the Vestals supervise sacrifices in her honor. Even the notorious emperor Nero (54–68 A.D.) involved the Vestals in the ceremony celebrating his coming of age, and he began rebuilding their sanctuary and household after the great fire of 64 A.D.

The house of the Vestals continued to be enlarged and made more luxurious by successive emperors as a sign of their devotion to the virgin priestesses. In the second century, the emperor Trajan (98–117 A.D.) established offices for the public distribution of grain right in the Vestals’ household. And in the third century, the Vestals’ atrium was used for public commemorations of the Vestals’ patronage of friends, family and dependents, advertising their power to advance people’s careers in the Roman government and military. It has been suggested that the large hall in their house also served as a site of the imperial cult, where worship of the divine emperors took place and thanks for imperial benefactions could be publicly registered.6

When a Vestal virgin converted to Christianity under the emperor Jovian (363–364 A.D.), there was much celebration by Christian writers. As the Roman empire became increasingly Christianized, pressure mounted to remove the Vestals. Despite the strong opposition of Roman pagans, the emperor Gratian stripped away the Vestals’ privileges and property in 375 A.D. There was, however, at least one practicing Vestal in 400 A.D. who carried out the traditional duties and protected the shrines of the state gods.

The Romans exported many aspects of their culture and encouraged the Romanization of new territories, but they never exported the cult of Vesta or the Vestal virgins. There were no other significant temples to Vesta and no other cults of her priestesses outside the city of Rome.7 The cult was simply too closely linked to the identity of Rome to be transplanted.

The Vestals, in many ways, were both a symbol of Rome and a means by which the city defined itself. It is no accident that as the civil wars broke out in the first century B.C., and as the Republic was transformed into the imperial monarchy, the Vestals were redefined: Their rights and privileges expanded as the number of Roman citizens increased. The role of the Vestals as intercessors between the emperor and his subjects served a vital function in an autocratic government in which official avenues for clemency were limited. Thus the Vestals embodied the chief qualities of the state: peace, prosperity and mercy.

In Book 6 of the Aeneid, Virgil describes the mission of Rome: parcere subiectis et debellare superbos, “to spare the subjected and subdue down the proud.” The emperors and their armies conquered proud enemies, but the Vestals upheld the Roman mission to spare the defeated and to incorporate them into the state. No wonder they were reluctant to retire from the cult. Why leave a position where, even as an unenfranchised woman, you possessed such power?

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Leaving the Vestal with food was supposed to absolve her executioners of any responsibility for her death; the virgin died not by human hands, but at the will of the gods.

Endnotes

Russell T. Scott, “Excavations in the Area Sacra of Vesta, 1987–1989,” in Eius Virtutis Studiosi: Classical and Postclassical Studies in Memory of Frank Edward Brown, ed. Russell T. Scott and Ann Reynolds-Scott (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1993), pp. 161–181.

Mary Beard, “The Sexual Status of Vestal Virgins,” Journal of Roman Studies 70 (1980), pp. 12–27. See her reconsideration of the problem, “Re-reading (Vestal) Virginity,” in Women in Antiquity, New Assessments, ed. Richard Hawley and Barbara Levick (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 166–177.

Tim Cornell, “Some Observations on the ‘Crimen Incesti’,” in Le Délit Religieux dans la Cité Antique (Rome: Ècole Française de Rome, 1981), pp. 27–37.

The severity of penalties the Vestals suffered has led one scholar to suggest that they actually lost full citizenship when inducted into the cult, taking on a unique status, not citizen, not alien, but fully sacred. See Ariadne Staples, From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion (London: Routledge, 1998).

On the development of Octavian’s propaganda of clemency and the role of the Vestals as agents of the emperor’s mercy, see my forthcoming book, Begging Pardon: Clemency and Cruelty in the Roman World (Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. of Michigan Press).

Arthur Darby Nock, “A Diis Electa: A Chapter in the Religious History of the Third Century,” Harvard Theological Review 23 (1930) pp. 251–274 (reprinted in Essays on Religion and the Ancient World, ed. Zeph Stewart [Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1972]).