Was John the Baptist an Essene?

018

The Dead Sea Scrolls, found between 1947 and 1956 in caves on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, provide us with a picture of a first-century Jewish community that could well have been the home of John the Baptist. At the very least, the possibility is worth exploring.

Whether or not the possibility is probable, however, is a question not easily answered. My own view is that the Baptist was raised in this community by the Dead Sea and was strongly influenced by it, but that he later left it to preach directly to a wider community of Jews.

Paradoxically, our sources in some ways portray John the Baptist more clearly than Jesus. It is certainly easier to place John in relationship to the contemporaneous Jewish community. Moreover, for 020John, we have an additional, non-biblical witness—the first-century Jewish historian Josephus.a Even among hypercritical exegetes, there is little doubt about who John was and what he stood for.

The Dead Sea Scrolls give us an extraordinary contemporary picture of a Jewish sect, living in the wilderness, with an outlook, customs and laws that seem to be very much like John’s.

Most scholars, including myself, identify the Dead Sea Scroll community as Essene—a separatist Jewish sect or philosophy described, along with the Pharisees and Sadducees, by Josephus.

Recently some few scholars have questioned whether the Dead Sea Scroll community was Essene.b They contend that the library of scrolls found in the Dead Sea caves represents broader Jewish thought. However this may be, it is clear that the library’s core documents—to which I shall refer—are, at the least, Essenic and represent the commitment of a Jewish community quite distinct from—even opposed to—the Jerusalem authorities.

Moreover, in the Judean wilderness, archaeologists have identified and excavated a settlement near the caves where the scrolls were found. According to Pliny the Elder (Historia Naturalis), the Essenes lived in just this location. Indeed, of the 11 caves with inscriptional material, the one with the greatest number of documents—Cave 4—could be entered from the adjacent settlement. It is difficult for me to understand the contention, recently put forward by one scholar,c that the settlement is unrelated to the library.

In any event, we shall assume that this settlement, which overlooks the Wadid Qumran, was Essene and that the sectarian documents found in the Qumran caves are also Essene.

As portrayed in the Gospels, John the Baptist stands at the threshold of the Kingdom. He marks the transition from Judaism to Christianity. Not only is the Gospel picture generally consistent with Josephus, but the four canonical Gospels are themselves in general agreement. In the case of John, there is little room for historical skepticism.

The Gospels portray John as a prophet who came out of the Judean wilderness to proclaim the Kingdom of God and to call for repentance. It seems clear that he had a successful ministry of his own, baptizing With water those who repented.

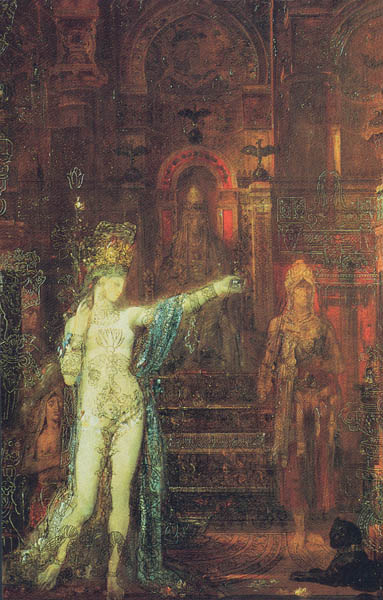

After Herod the Great died in 4 B.C., his son Herod Antipas became tetrarch of Galilee. John denounced Antipas’ marriage to Herodias, his half-niece, who had abandoned her previous husband. Antipas threw John into prison for his criticism. Antipas’ new wife Herodias, however, was to go one step further. At Antipas’ birthday party, Salome—Herodias’ daughter by her previous marriage and now Antipas’ stepdaughtere—danced for Antipas, who was so delighted with her 021performance that he promised on oath to give Salome whatever she desired. Induced by her mother Herodias, Salome asked for the head of John the Baptist on a platter. Antipas was unhappy at the request but was bound by his oath. He had John beheaded in prison, which Josephus locates at the fortress of Machaerus, east of the Jordan (Antiquities of the Jews 18:119), and his head was duly delivered to Salome on a platter (Matthew 14:3–12; Mark 6:17–29).

John’s stature is reflected in the fact that when Antipas is informed of Jesus’ ministry and wondrous deeds, his first thought is that John had been resurrected and had come back to life (Matthew 14:1–2; Mark 6:14–16; Luke 9:7–9).

The Gospels portray John as the forerunner of Jesus. Jesus himself proclaims John’s stature: “Truly, I say to you, among those born of women there has risen no one greater than John the Baptist” (Matthew 11:11; compare Luke 7:28). John, Jesus tells the crowd, is “more than a prophet” (Matthew 11:9; Luke 7:26). Indeed, “he is Elijah to come” (Matthew 11:14), the traditional precursor of the Messiah. Jesus himself was baptized by John (Matthew 3:13–17; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–22). It is clear that the populace considered John a true prophet (Matthew 21:26; Mark 11:32; Luke 20:6).

According to Josephus, John “was a good man and had commanded the Jews to lead a virtuous life” (Antiquities of the Jews 18:117).

Years after Jesus’ death, Paul encountered a man in faraway Ephesus (in Asia Minor) who “knew only the baptism of John” (Acts 18:25). John’s movement apparently endured (see Acts 19:3).

According to the third- and fourth-century pseudo-Clementines (Recognitiones 1.60), John’s disciples claimed that their master had been greater than Jesus and that John was the true messiah.

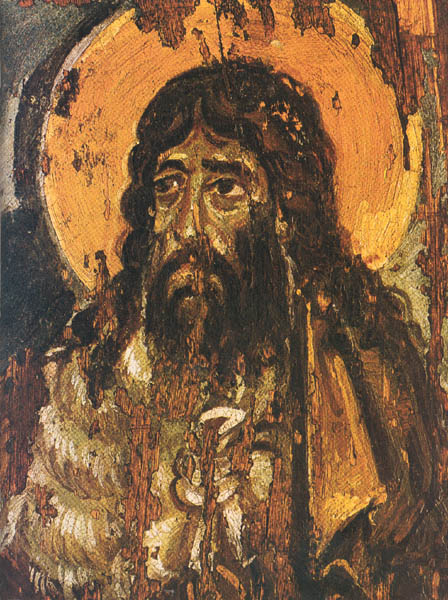

John the Baptist has been Immortalized through innumerable works of art-novels, operas, movies and especially paintings—showing the prophet preaching in the desert, baptizing in the Jordan River or pointing to the lamb of God We see him as a prisoner in a dark cell, or sometimes we see only his bloody head on a platter being delivered to the beautiful Salome. The Baptist was also a favorite of icon painters. As the prodromos, the precursor of Christ, he stands at the left hand of the Judge of the World.

More than 20 years ago, when I was teaching at the University of Chicago, one of my black students said to me, “I want to be like John: a voice in the desert, crying for the outcasts, unmasking the hypocrites, showing the sinners the way to righteousness!” A year later the wave of student revolts had reached my own university at Tübingen, where I had returned. I recall a good Christian student who suddenly declared: “Please, not Jesus! John the Baptist is my man!” And he gave up his theological studies.

It is not surprising that the discovery and partial publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls has led to speculation that John the Baptist was an Essene who lived at Qumran. The Essenes flourished at 022Qumran at the same time John was preaching and baptizing people in the nearby Jordan River. The Qumran settlement was destroyed by the Romans in about 68 A.D. as part of their effort to suppress the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 A.D.), which culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem.

The Dead Sea Scroll known as the Manual of Discipline, also called the Rule of the Community (designated by the scholarly siglum IQS, which stands for “Qumran Cave 1, Serekh ha-Yahad,” the Hebrew name given to the scroll text), appears to be the main organizational document of the Qumran community. There we read that the people of the community must separate themselves

“from the dwelling-place of the men of perversion [the Jerusalem authorities] in order to go to the wilderness to prepare there the way of HIM, as it is written [quoting Isaiah 40:3]: ‘In the wilderness prepare the way of …. [the divine name is marked in this scroll by four dots], make straight in the desert a road for our God!’—this (way) is the search of the Law” (Manual of Discipline 8:13–15).

The Essenes were thus led to the wilderness by the same scriptural directions that motivated the life and ministry of John. The early Christians understood John as “ ‘the voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight’ ” (Mark 1:3). This passage from Mark quotes the same words from Isaiah 40:3 that are quoted in the Qumran Manual of Discipline.

The Qumran settlement and the adjacent caves where the scrolls were found are located in the 023vicinity of the traditional place of John’s activity near Jericho.

Luke’s account of John’s birth ends with the astonishing remark: “And the child grew and became strong in spirit, and he was in the wilderness till the day of his manifestation to Israel” (Luke 1:80). How could this little child, the only son of aged parents, grow up in the wilderness? Well, the Essenes lived there, leading a kind of monastic life. According to Josephus, they would receive the children of other people when they were “still young and capable of instruction” and would care for these children as their own and raise them according to their way of life (The Jewish War 2:120). It would seem that John the Baptist was raised at Qumran—or at a place very much like it—until he became the voice of one crying in the wilderness, calling for repentance.

Correspondences between the life and teachings of the Qumran community and the life and teachings of John are often extraordinary.

John’s baptism, as we learn from the Gospels, is but the outward sign of the reality of repentance and the assurance of God’s forgiveness (Mark 1:14). After the penitent people had confessed their sins, John baptized them. This probably consisted of immersion in the waters of the Jordan River. However, without the “fruit worthy of repentance” (Matthew 3:8), this rite of purification was useless; as Josephus puts it: “The soul must be already thoroughly cleansed by righteousness” (Antiquities of the Jews 18:117). In the Manual of Discipline (3:3–8) we read that cleansing of the body must be accompanied by purification of the soul. Someone who is still guided by the stubborness of his heart, who does not want to be disciplined in the community of God, cannot become holy, but instead remains unclean, even if he should wash himself in the sea or in rivers; for he must be cleansed by the holy spirit and by the truth of God.

According to the Gospels, John the Baptist announced the coming of a “Stronger One” who would baptize with the Holy Spirit and with fire (Mark 1:7–8). The Qumran community had a similar expectation: They anticipated that their ritual washings would be superseded with a purification by the Holy Spirit at the end of time; then God himself would pour his spirit like water from heaven and remove the spirit of perversion from the hearts of his chosen people. Then they would receive the “knowledge of the Most High and all the glory of Adam” (Manual of Discipline 4:20–22).

In Matthew 21:32, we read that Jesus himself said that “John came to you in the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him … [E]ven when you saw it, you did not afterwards repent and believe him.” Similarly with the high priests and elders in Jerusalem who did not accept John (Matthew 21:23–27). John may be compared with the most influential man in the Qumran movement, the Teacher of Righteousness. This great anonymous figure announced the events that would come upon the last generation, but the people who “do violence to the covenant” did “not believe” his words (Commentary on Habakkuk 2:2–9).

The Teacher of Righteousness was the priest ordained by God to lead the repentant to the way of His heart (Commentary on Habakkuk 2:8; Cairo Damascus Document 1:11). His teaching was like that of a prophet, inspired by the holy spirit. John too was a priest, the son of the priest Zacharias (Luke 1:5). Like the Qumran Teacher of Righteousness, John separated himself from the priesthood in Jerusalem and from the service in the Temple. And, like the Teacher of Righteousness, he was also a prophet.

Both the Teacher of Righteousness and John the Baptist remained faithful to the laws of purity; they both practiced them in a radical, even ascetic, way. Both the Teacher of Righteousness and John the Baptist believed that the messianic age and the final judgment were soon to come. That is why both practiced the purification of body and soul in such a strict way. The prophetic call for repentance and the apocalyptic expectation of the end of history led to the radicalization and generalization of the priestly laws of purity.

We are told that John the Baptist “did not eat nor drink” (Matthew 11:18), which means that he lived an ascetic life, eating locusts and wild honey (Mark 1:6), foods found in the desert. John wanted to be independent, unpolluted by civilization, which he considered unclean. In this he was not unlike the Essenes living at Qumran. John’s cloak was made of camel’s hair, and the girdle around his waist was leather, well suited to his aim of strict purity.

In ancient Israel the spirit of prophecy often opposed the theology of the priests (see, for example, Amos 5:22; Isaiah 1:11–13; Jeremiah 7:21–26). The prophets warned the people not to rely too heavily on the Temple and on the atoning effect of sacrifice. Both the Essenes and John the Baptist, however, succeeded in combining the prophetic and the priestly ideals in a holy life, ritually pure but characterized by repentance and the expectancy of the final judgment. John’s disciples were known to fast (Mark 2:18) and to recite their special prayers (Luke 11:1). These two acts of piety also appear in the Qumran texts. Infraction of even minor rules was punished by a reduction in the food ration, 024which meant severe fasting (Manual of Discipline 7:2–15). And there are several special prayers in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Among them are the beautiful Thanksgiving Hymns from the scroll found in Cave 1. Cave 11 also produced a scroll of psalms in which new prayer were inserted into a series of Psalms of David.

The Qumran Essenes separated themselves from the Jerusalem Temple and its sacrificial cult. The Temple’s offerings of animals were replaced by the “offerings of the lips” (that is, prayers) and by works of the Law. Man must render himself to God as a pleasing sacrifice; he must bring his spirit and body, his mental and physical capacities, together with his material goods and property, into the community of God. In this community all these gifts will be cleansed of the pollution of selfish ambition through humble obedience to the commandments of God (Manual of Discipline 1:11–13).

The Qumran community was intended to be a living sanctuary. They believed this living temple, consisting of faithful people, rendered a better service to God than the Jerusalem sanctuary made of stones. The chosen “stones” of the community were witnesses to the truth of God and made atonement for the land (Manual of Discipline 8:6–10); in this way, the community protects the land and its people from the consuming wrath of God and the catastrophe of his judgment. The Jerusalem Temple could not do this as long as disobedient priests served in it.

John the Baptist, the son of a priest, also had a conflict with the Jerusalem hierarchy, similar to the conflict of the Essenes with the Jerusalem hierarchy. He must have shared the Essenes’ belief in the superior quality of the spiritual temple of God. He warned the people not to rely on the fact that Abraham was their father, for “God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham [that is, a truly repentant community]” (Matthew 3:9). This famous saying contains a marvelous play on words in Hebrew. “Children” is banim; “stones” is abanim. The saying thus presupposes the idea of a living temple “of men.” John is saying that God can create genuine children of Abraham “from these stones” and build them into the sanctuary of His community.

In the Temple Scroll from Qumran, God promises that he will “create” a sanctuary at the beginning of the new age; this he will do according to the covenant made with Jacob at Bethel (Temple Scroll 29:7–10). At Bethel, Jacob had declared: “This stone [the pillar that Jacob had erected] shall become the house of God” (Genesis 28:22). Both the Qumran community and John the Baptist believed in the creative power of God that will manifest itself at the end of time, as it did in the beginning. Then God will establish the true sanctuary and the ideal worship, which are anticipated both in the life of the Qumran community and in the life that John preached.

John’s preaching had several characteristics that can also be found at Qumran. For example, John used prophetic forms of rebuke and threat (Matthew 3:7–10). The hypocrites who came to him for baptism without repenting he called “a brood of vipers” (Matthew 3:7). I believe this strange term is the Hebrew equivalent of

While there are thus many reasons to suppose that John the Baptist was an Essene who may have lived at Qumran, there are also impediments to this conclusion that must be as assiduously pursued as the correspondences.

First, John is never mentioned in the Dead Sea Scrolls that have been published so far.

Perhaps more telling is the fact that John is never called an Essene in either the New Testament or in Josephus. The absence of such a reference is especially significant in Josephus, because in both Antiquities of the Jews and The Jewish War Josephus discusses the Essene sect several times as a Jewish “philosophy” on a par with the Sadducees and the Pharisees. In The Jewish War (2:567), Josephus even mentions another John, whom he identifies as “John, the Essene,” who served as a Jewish general in the First Jewish Revolt against Rome. Josephus also identifies three prophetic figures as Essenes (although he does not call them prophets). All of this indicates that Josephus would have identified John the Baptist as an Essene if he knew him to be a member of that group.

Even more significantly, John the Baptist was outspokenly critical. of the civil government, which would be uncharacteristic of an Essene. The Baptist went so far as to criticize the tetrarch Antipas himself for marrying his “brother’s wife” (Mark 6:18). With his preaching, John created such excitement among the crowds that Herod became afraid that this might lead to a revolt (Antiquities of the Jews 18:118). John’s outspokenness seems unlike an Essene.

A similar objection can be raised regarding John’s courageous concern for the salvation of his Jewish countrymen. This too seems unlike the Essenes. Indeed, after some serious but unsuccessful criticism 025of the religious and political leaders in the second century B.C., the Essenes seem to have withdrawn from public life in order to work out their own salvation. They never developed missionary activity, but preferred simply to wait for those whom God chose to join their community of salvation.

John the Baptist, on the other hand, dared to address all the people. He became the incarnation of the divine voice, calling from the desert into the inhabited world: “I am the voice of one calling in the wilderness” (John 1:23). John did not relegate people to a sacred place in the desert, nor did he incorporate them into a holy community with monastic rules. Rather, after they had confessed their sins, he baptized them once and for all. Then he sent them back to their profane world—to their work and their families. There they were to enjoy the “true fruits of repentance” in a life of righteousness. This does not sound at all like an Essene.

For these reasons, we could easily conclude that John the Baptist was not an Essene. The Essene community, on the one hand, and John, on the other, seem to have lived in two different worlds: the one a closed community of saints whose sole concern was for their own salvation; the other, a lonely prophet who was concerned for all his people and their salvation.

But this is not the end of the discussion. There is a way to reconcile the pros and cons.

As Josephus reminds us, not all Essenes led a monastic life in the wilderness of Judah. Indeed, some sound almost like John the Baptist. Josephus even speaks of Essene prophets. Nor were these pseudo-prophets, impostors and deceivers, of whom Josephus has much to say, but men who foresaw and told the truth, much like the classic prophets of ancient Israel. These Essene seers appeared suddenly, standing up to kings, criticizing their conduct or foretelling their downfall. Josephus does not describe their teaching and way of life; he simply characterizes them as Essenes (The Jewish War 1:78–80, 2:112–113; Antiquities of the Jews 15:371–379).

In short, there is no clear-cut conflict between the priestly way of life (= Essene) and the prophetic. Both biblical traditions—the priestly one and the prophetic one—influenced the Essenes just as they did John the Baptist.

I believe that John grew up as an Essene, probably in the desert settlement at Qumran. Then he heard a special call of God; he became independent of the community—perhaps even more than the Essene prophets described by Josephus. With his baptism of repentance, John addressed all Israel directly; he wanted to serve his people and to save as many of them as possible.

The Essenes of Qumran no doubt prepared the way for this prophetic voice in the wilderness. They succeeded in combining Israel’s priestly and prophetic heritage in a kind of “eschatological existence.” The Essenes radicalized and democratized the concept of priestly purity; they wanted a true theocracy and sought to turn the people of God into a “kingdom of priests” (Exodus 19:5–6).

A particular motif of their peculiar piety was the eschatological hope. In the age to come, they believed, there would be only one congregation of holy ones in heaven and on earth; then angels and men would worship together. Therefore, the liturgy and the sacred calendar used in heaven for the time of prayer and the celebration of the feasts served as a model for Essene worship even in the present. In heaven, animals are not sacrificed and offered to God; the angels use incense and sing hymns of praise. Therefore, on earth they had no need of the Jerusalem Temple. The Essenes believed that a living sanctuary of holy men could render a more efficient ministry of atonement than animal sacrifices, offered by an unclean priesthood (Manual of Discipline 8:6–10; 9:4–5).

But the Essenes also incorporated the traditions of the prophets into their beliefs. The prophet had little if anything to do with the Temple and sacrifice; the prophet tried to accomplish atonement through his personal commitment and effort to change the hearts of his audience. Because the Essenes were a movement of repentance, they adopted the prophetic tradition, despite their leadership of priests. Their Teacher of Righteousness was a priest who acted in a prophetic way.

This was true as well for John the Baptist. He was the son of a priest and practiced the laws of priestly purity in a radical way. But in his ministry for Israel he acted as a prophet, as the Elijah redivivusf to announce the coming of the Messiah. In his baptism, both traditions were combined, just as they were in the Essene philosophy: the priestly laws of ritual purity were combined with the prophetic concern for repenting, returning to God and offering oneself to Him. Accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that John the Baptist was raised in the tradition of the Essenes and may well have lived at Qumran before taking his message to a wider public.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, found between 1947 and 1956 in caves on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, provide us with a picture of a first-century Jewish community that could well have been the home of John the Baptist. At the very least, the possibility is worth exploring. Whether or not the possibility is probable, however, is a question not easily answered. My own view is that the Baptist was raised in this community by the Dead Sea and was strongly influenced by it, but that he later left it to preach directly to a wider community of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Lawrence H. Schiffman, “The Significance of the Scrolls,” BR 06:05.

A wadi is a dry river or stream bed that flows briefly, once or twice a year, during the winter rainy season.