032

033

Think small.

No, think minute!

Think something seemingly unimportant, but invaluable.

Think seeds and weeds and grains—grown over 2,500 years ago.

Our story takes place in the late seventh century B.C.E. in the thriving Philistine city of Ashkelon, on what is now the Mediterranean coast of Israel. In 604 B.C.E., Ashkelon was utterly destroyed by Nebuchadrezzar (or Nebuchadnezzar), the Babylonian leader who later destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon’s Temple in 586 B.C.E.

The background: The Babylonians, having defeated the Assyrians, succeeded to Mesopotamian hegemony. Egypt, meanwhile, moved in to control the states in the southern Levant—chiefly Philistia and Judah—that had effectively been Assyrian provinces. Babylon sought to assert its own dominance in this area of former Assyrian domination. A struggle between the world’s two superpowers—Babylonia and Egypt—ensued.

In 609 B.C.E. the Babylonians defeated the Egyptians in a critical battle at Carchemish, in western Syria. When that campaign ended in 605 B.C.E. Nebuchadrezzar headed south. On his new campaign, Jerusalem was spared, but numerous Mediterranean coastal cities fell to the Babylonian onslaught. One of them was Ashkelon. Ashkelon was destroyed in November/December 604 B.C.E. We know almost the exact date from a Babylonian chronicle:

“(Nebuchadrezzar) marched to the city of Ashkelon and captured it in the month of Kislev (November/December). He captured its king and plundered it and carried off [spoil from it …]. He turned the city into a mound and heaps of ruins.”1

Archaeologists love destructions. That is their bread and butter, so to speak. When someone peacefully deserts his house—say, when a family seeks a better home—in most cases everything is removed from the dwelling, especially the reusables. The house itself may be torn down for a new one. Even the roof beams and construction material will be removed. What will that leave for us, the archaeologists? Almost nothing. Destructions, however, especially those caused by an army so fearsome that it would “turn the city into a mound and heap of ruins,” instantly freeze the life of the house and leave its contents for archaeologists to find and explore thousands of years later.

Nebuchadrezzar’s destruction of Ashkelon did just that.a The conflagration froze Ashkelon in time and preserved a wealth of materials, including carbonized seeds and fruits. For archaeobotanists like us, this is a treasure trove.

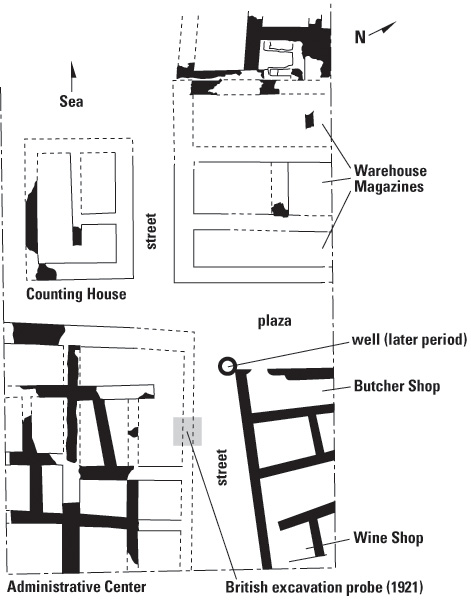

We concentrated on one small area of the site called Grid 50. For archaeological purposes, the 150-acre site is laid out on a grid. Grid 50 is adjacent to the sea. Lawrence Stager, director of the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, calls this grid “the market.” The area was burned so completely that in some places the sun-dried mud-bricks were vitrified (transformed into glass).

This grid contains four buildings, separated by streets, and a plaza. Stager identifies the four buildings as the Warehouse, the Shops Building, the Counting House and the Administrative Center.

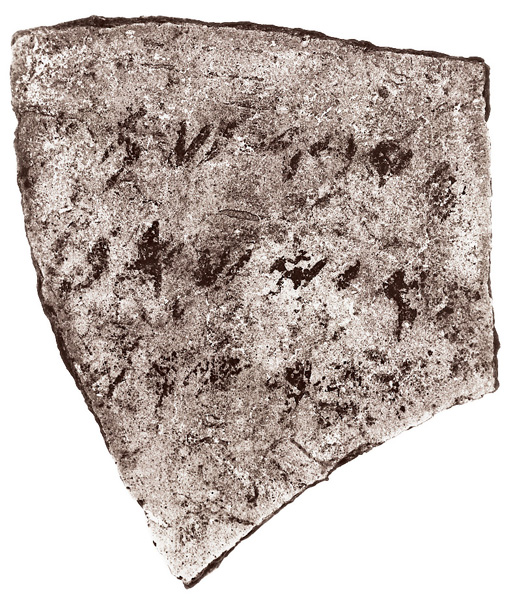

Some of the particular shops in the Shops Building can be identified. One (Room 423) was a wine shop. The floor of the wine shop was littered with dipper 034juglets and wine jars. Just outside, an ostracon (a pottery sherd with writing on it) that refers to wine and other strong drinks was found.

Another room (Room 431) of the Shops Building appears to have been a butcher shop. Inside, excavators found animal bones reflecting different cuts of meat.

The Warehouse consists of several long, narrow rooms, or magazines, adjacent to one another.

In the Counting House the excavators recovered scale weights, two fragments of bronze pans (for weighing) and part of a bronze beam of a balance scale. Another ostracon appears to be a receipt for grain paid for in silver.

From the streets and rooms of Grid 50, we removed 138 botanical samples. In these samples we identified nearly 20,000 plant remains, including nearly 7,000 cereal grains, more than 9,000 fruit seeds and nearly 2,000 weed seeds. The rest were pulses (edible seeds from leguminous plants) such as peas, beans, lentils and wild plants. For the most part, they were charred from the fire, which is what preserved them.

What could we learn from this humble collection? The brief answer: A lot.

First, however, you might wonder how we collect the samples. We use something called a flotation tank. The debris from the various loci (what we call the “fine grid”) are poured into a barrel of water. Immersed in the barrel is a screen with holes 1.5 millimeters on a side; nothing larger than this will fall through. Some finds, like charred plant remains, are so lightweight, however, that they float on the surface. This we call 035the “light fraction.” We simply skim this off with a strainer whose holes are only 0.6 millimeters on a side. Then we raise the larger screen that has caught the heavier pieces, which we call the “heavy fraction.”

The plant remains are then picked out and identified in the laboratory with the aid of a stereomicroscope using magnifications up to 50x. An extensive reference collection of seeds and fruits from almost all plant species that grow in Israel, and many from the adjacent countries, helps us to identify these ancient finds. This reference collection is kept in the archaeobotanical laboratory in Bar-Ilan University, near Tel Aviv.

From all this work we learned what these Philistines ate: wheat, barley, almonds, figs, grapes, olives, pomegranates, chickpeas and lentils, to name the most important foods. This vegetarian part of their diet did not surprise us. During that time, many years after they settled in the country, the Ashkelonian Philistines’ “menu” was similar to that consumed at other contemporaneous sites throughout the Levant.

We may also have found evidence of the use of some medicinal plants such as bay laurel. Bay laurel is frequently mentioned in ancient medical literature; for instance, a massage of bay laurel oil was employed in antiquity to alleviate joint pain and neuralgia and as a balm for healing wounds. Boiled berries and leaves were used to prevent diarrhea. A tincture of bay laurel berries was said to enhance sexual potency. Other written sources indicate that laurel fruits were used by the Assyrians as an eye treatment, to make bandages and for the treatment of urinary-tract infections. And of course bay leaves are also a spice.

Bay laurel does not grow in the Ashkelon area today, and it is unlikely to have grown there in ancient times. The nearest places where this tree now grows are in the hills of Judea and Samaria, some 30 or 40 miles to the east. Also, the bay laurel was found in the Counting House. It was not found in the Warehouse or Shops, perhaps indicating it was a special commodity.

Weeds present a special problem—both for ancient farmers and for modern archaeobotanists. The level of weed infestation in grain brought to Ashkelon is high. The proportion of grain to weeds is about three to 037one. The heavy weed infestation probably indicates that the farmers were eager to harvest their wheat fields and that the Ashkelon inhabitants were just as eager to buy wheat, in anticipation of the imminent Babylonian siege of the city. Remember that this grain was in Ashkelon when the city was destroyed. As news of the approaching Babylonian army reached the city, no doubt there was an effort to accumulate food from every source, near and far, cheap or expensive.

We have even been able to determine the fields where some of the grain was grown. The largest wheat concentration we examined was in the Counting House. We call these wheat concentrations “wheat piles.” The wheat piles contain a variety of species of wheat grains and weeds. Since each of these piles was found burned, buried and sealed under destruction debris, each was probably accumulated in a single event. The sack or other perishable container that originally held the wheat did not survive the fire. The concentration of large amounts of wheat and grains and well-known weeds in the same pile suggests that the pile represents a load of wheat from a single field.

Some of the species do not grow in the Philistine plain, but in the Shephelah, the Sharon plain, and the Samarian and Judean hills. By determining which species grew in close proximity, we were able to narrow the locations still further: either the Sharon plain or the Judean hills. We have thus been able to determine the probable source of some of the wheat piles.

Thus archaeobotany has uncovered evidence that ancient Ashkelon imported much of its food from some distance. The best estimate is that in ancient times about 4 acres of land was needed to supply food for one person for one year. Stager, Ashkelon’s excavator, estimates a population of 10,000-12,000 for the site. Another leading study estimates that the distance between settlements and the local fields supplying them with plant food was commonly less than 7 kilometers (about 4.3 miles).2 There are only 2,700 acres within a 7-kilometer radius of Ashkelon, however. The city’s own fields, therefore, could have supported only 675 people!

The Ashkelon economy could not have relied on the fields around the city, so regular, long-distance trade in crop plants, such as cereals, must have occurred, as our weed distribution suggests.

The abundance of Phoenician pottery found at the site indicates an important northern trade route. The plant remains provide independent evidence for this suggestion. If wheat had been transported to the city market from the north by ship, it could have come from many other seaports along the eastern Mediterranean coast, such as Jaffa, Dor, Acco, Tyre and Sidon. Five of the principal varieties of plants we investigated grow along the Mediterranean coastal plain from Israel to Lebanon. Apparently there was a brisk trade in comestibles among cities of the coast, especially between the Philistines and Phoenicians. Historical support for this suggestion is provided by Jeremiah 47:4, where the prophet describes the Philistines and the Phoenicians (Tyre and Sidon) as allies.

The archaeobotanical remains thus provide additional elements to the picture of an ancient Philistine city’s economy and food supply on the eve of its fiery destruction.

Think small. No, think minute! Think something seemingly unimportant, but invaluable. Think seeds and weeds and grains—grown over 2,500 years ago. Our story takes place in the late seventh century B.C.E. in the thriving Philistine city of Ashkelon, on what is now the Mediterranean coast of Israel. In 604 B.C.E., Ashkelon was utterly destroyed by Nebuchadrezzar (or Nebuchadnezzar), the Babylonian leader who later destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon’s Temple in 586 B.C.E. The background: The Babylonians, having defeated the Assyrians, succeeded to Mesopotamian hegemony. Egypt, meanwhile, moved in to control the states in the southern Levant—chiefly Philistia and Judah—that […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Lawrence E. Stager, “The Fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the Archaeology of Destruction,” BAR, January/February 1996.