Were Christians Buried in Roman Catacombs to Await the Second Coming?

016

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Marble Faun, a novel about young artists struggling to learn their craft in 19th century Rome, a group of painters visits the catacomb of Callistus on the old Appian Way. As they wander through the tunnels, their way lit by flickering candles, one of the young women becomes separated from the rest. She was lured away by the Ghost of the Catacombs!

The Ghost of the Catacombs, Hawthorne explains, is a “man-demon” who originally “was a [Roman] spy during the persecutions of the early Christians under the Emperor Diocletian” (293–305 A.D.). This man-demon, Memmius, as he was known, scoured the catacombs for 018Christians hiding from the arm of the Roman law. Memmius had the opportunity to be saved by conversion, but he resisted and was condemned thereafter to wander through “the wide and dreary precincts of the catacomb, seeking to beguile new victims into his own misery. … ”

In Hawthorne’s time, it was reported that a young French lieutenant was lost for days, and only by a stroke of good fortune managed to find his way out. He promptly renounced his atheism and became a Christian. When he died in battle years later, a copy of the New Testament was found in the pocket over his heart. Perhaps this incident provided the background for the episode in Hawthorne’s novel.

Hawthorne’s picture still influences the way most people think about the catacombs. They are dark, mysterious places, the perfect home for ghosts. They recapture in the imagination the period of persecutions of the young Church, a time of testing of the faith against the powerful forces of the Roman Empire. They represent the darkness before the dawn of the Peace of the Church under Constantine in 312 A.D. It is a mixture made to order for the romantic author of the last century or the neo-romantic of our own.

One of the most enduring myths about the catacombs is that they were places of refuge during the persecutions. Christians could meet in secret and worship while the lions of the arena roared for their daily ration of martyrs. Novelists and movie makers alike have perpetuated such images (Quo Vadis, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, etc.). Church historians have also done their part, painting lurid scenes of Christians huddled in the catacombs, fleeing the wrath of the emperors.

As with most legends, a kernel of historical truth can be found here. That the catacombs were places of refuge was a reason for Pope Paul I to complain in the mid-eighth century that thieves, debtors, outlaws, and bandits found them splendid hide-outs; shepherds of the Campania were using them for sheepfolds.

021

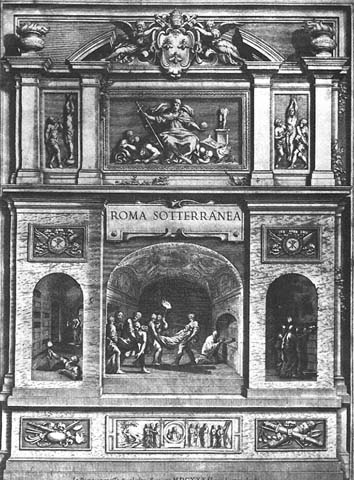

The accounts of the rediscovery of the catacombs in the 17th century read like reports coming from a new world. Little wonder that Antonio Bosio, their great discoverer and author of Roma Sotteranea (Subterranean Rome), was later dubbed the “Columbus of the Catacombs.” Underneath Rome was a world of the early Church waiting to be charted, if you could find the gateways. Pilgrim records were searched for clues. Reports from the Middle Ages were checked for the routes taken by pilgrims on their visits to the shrines of martyrs. By retracing the steps of these pilgrims, searchers hoped to locate these shrines and tombs again. In this way, dozens of catacombs were rediscovered. Some, however, fell right back into obscurity. The catacomb of a family named Jordani was visited in 1578 when it was accidentally discovered in the course of road repairs. Copies of the paintings and inscriptions were made, but the work remained unpublished until 1856. The catacomb itself was not seen again until 1921, when construction work led to its rediscovery.

Otto Beyer, a German scholar, calculated that the catacomb tunnels of Rome meander over 600 miles. Just how he arrived at the estimate is uncertain. Even today, no one knows whether all of the catacombs have been found.

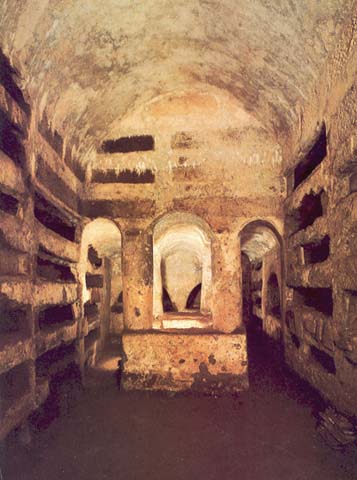

The less romantic side of the picture is that catacombs are underground graveyards and passageways cut out of a soft, porous stone called tufa. Professional graveyard diggers, fossores, carved burial niches or loculi, and numerous chambers, cubicula, for burial of the dead. Designed as communal graves, the catacombs were used for approximately two hundred years—between the second and fourth centuries A.D.

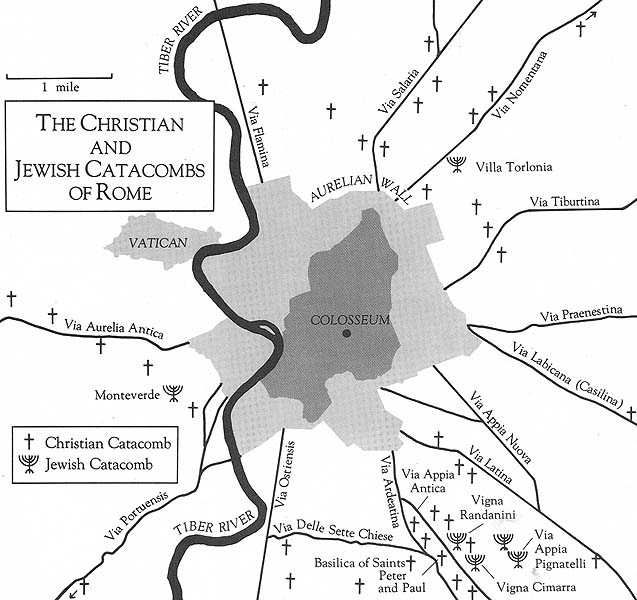

Roman law did not permit graveyards to be located within the city walls, so the catacombs are found in a circle around ancient Rome, chiefly to the south, east, and north.

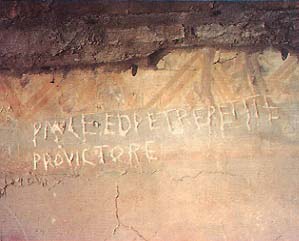

In ancient times small clay oil lamps were used to light 022the way down a stairway to the series of passageways which comprised the catacomb. The stairs and passageways are flanked with four to six (loculi) tiers. Each loculus (singular) is approximately six feet long and one and a half to two feet wide. Clay tiles or pieces of stone were set in mortar to seal the opening to the loculi. The name and frequently the age of the deceased would be painted or carved on the loculus seal.

Some catacombs are quite small, consisting of one or two passageways and only a few chambers (or cubicula). These catacombs may have originally begun as a family plot, but in time the plot was acquired by the church and became a communal burying site.

When the number of burials exceeded the space inside a catacomb, a new level could be cut deeper into the ground or the passageway lengthened. One of the largest catacombs in Rome, named for a Pope Callistus, has three levels cut into the earth.

Only a few catacombs are open to the public today, but these give the visitor, whether pilgrim or tourist, the flavor and atmosphere of the world of the early Church.

Although people commonly associate the catacombs with Christianity and Rome, catacombs are neither a Christian nor a Roman invention. Those in Rome represent a culmination of several lines of development: Etruscan, Roman, and Jewish burial customs.

The first underground burial chambers, or hypogea, are found at Etruscan sites in Italy as well as other sites around the Mediterranean. These tombs usually include single rooms approximately 12 feet by 15 feet. Sometimes more than one burial is found in a hypogeum. Bodies were placed in coffins and bones were kept in ossuaries.

The mausoleums of Rome provide another line of development for the catacombs. Mausoleums themselves are small buildings reserved for the funereal needs of one family. Inside would be a place for the family sarcophagi and for burial urns that held the ashes of members of the family and their slaves. Wealthy families would construct these buildings along the major roads leading out of Rome, such as the Appian Way. Some of these mausoleums were built in a small gully south of Rome. Over a century later when Constantine ordered a church built to honor Saints Peter and Paul, the mausoleums were buried under tons of earthfill. Archaeological excavations under the church dedicated to these apostles (renamed Saint Sebastian in the fourth century) revealed this gully with its three remarkably preserved pagan family mausoleums from the second century A.D.

By the beginning of the third century some of these family tombs were acquired by the Church and under its administration the properties were expanded into community cemeteries by tunneling.

This expansion into communal burial areas accounts for a third line of influence on the catacombs: Jewish burial practices (see “A Rare Look at the Jewish Catacombs of Rome” by Letizia Pitigliani, in this issue). According to Jewish tradition, every member of the community was entitled to a burial ceremony—rich or poor, honored or hated. Unlike the pagan tradition, cemeteries were not limited to wealthy families who could afford to own them. Rather, communal burial of the dead was an important responsibility of the synagogue. Every synagogue—whether in Israel or Greece or Rome—owned a cemetery which its members were entitled to use. Thus we are not surprised to learn that Antonio Bosio, the “Columbus of the Catacombs” found a Jewish catacomb in Rome in 1602. It was a simple affair. Most of the epitaphs, he reported, had been destroyed by grave robbers, but one fragment still had the word “synagogue.” A terra cotta lamp, still intact, bore a seven-branched candelabrum. The absence of any Christian signs in the tomb confirmed Bosio’s conclusion that he had found “a particular cemetery of ancient Hebrews,” Five more Jewish catacombs were found between 1853 and 1919. Over fifty Christian catacombs have been discovered, 023some of which have been built on a scale much greater and more complex than their Jewish counterparts.

Otherwise, Jewish and Christian catacombs differ very little from one another. The variations in structure and architectural styles between the two groups are no greater than the variations among the Christian examples. What comes as a surprise is that until the 4th century A.D., almost all the epitaphs in the Jewish catacombs were written in Greek. The earliest Christian epitaphs were also in Greek, but in the course of the third century a shift to Latin took place. By the fourth century both Jewish and Christian epitaphs were written in Latin. This change of languages is an indication of the respective histories of these two communities in Rome. Both groups had the same origin in the immigration of Greek-speaking Jews from the eastern Mediterranean, but by the beginning of the second century A.D., the Christian branch was becoming assimilated into Roman society and began to adopt Latin as their language. For its part, the Jewish community remained closer together and retained their language ties with the east.

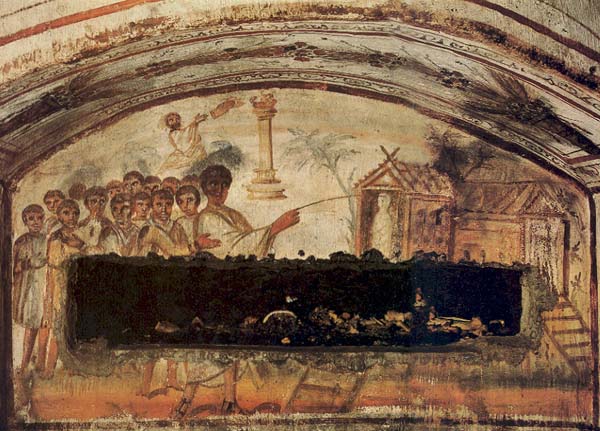

Their shared Biblical heritage and Hellenistic tradition caused the two communities to choose some of the same decorative symbols: birds, dolphins, lions and trees. But the rest of their artistic vocabularies diverges. In Jewish catacombs, signs well-known from Jewish coins decorate their burial chambers: the etrog [citron], the shofar, the scroll of the Law, the Torah shrine, and above all, the seven-branched menorah. These symbols of Jewish tradition, of course, appear nowhere in Christian tombs. In the latter, we find narrative scenes from the Bible: Jonah and the Great Fish, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, Noah and the Ark—all repeat the theme of deliverance and remind us that the early Church never rejected the Jewish Bible even when it broke with the synagogue.

The differences in Christian and Jewish funereal art stem from their divergent religious concerns: The Jews’ was with observance of the Law; the Christians’ was with deliverance from sin and death through divine intervention.

The disparity in number and size between Jewish and Christian catacombs is a puzzle. The Jews were a minority of the Roman population and the Christians were an offshoot of the Jews, a kind of minority within a minority. Even if Gentile converts are included in the Christian population, this cannot explain why the Christian catacombs outnumber the Jewish catacombs by more than eight to one.

The population of ancient Rome is difficult to determine because we do not have any really reliable records. Estimates for the population of Rome in the time of Augustus (first centuries B.C.–A.D.) range from 760,000 to 980,000, but for the era of Constantine, (fourth century A.D.) the figures drop to 200,000 to 500,000. Adolf Harnack, a great church historian of the last century, estimates that the percentage of Christians living in Rome rose from three to five percent in the first century A.D. to at least ten percent by the time of Constantine. This means that even if estimates of the percentage increase in Christians is correct, the actual number of believers would still decline in those first three centuries from 40,000 to 35,000.

If we assume a death rate of about 6.3%, the number of Christian dead turns out to be rather smaller than generally expected—at most 3,700 per year.

But Otto Beyer, the same German scholar who estimated that the catacombs contained more than 600 miles of passageways, says that the catacombs hold five million graves. Beyer does not inform us how he derived this number. But even if Beyer has greatly overestimated the number, the Christian population in Rome can account for only a very small percentage of the burials in the Christian catacombs. Who, then, is buried in these catacombs which Bosio claimed held “an infinite number of martyrs?”

024

Perhaps many of the burials are pagans. That they were interred along with the Christians in the same catacombs is not impossible. This could help explain why some gravestones are marked with Christian symbols and others are not. The fragmentary state of so many epitaphs makes it impossible to be certain about this. Cremation had been common among the Romans until the first century, A.D., when a preference for burial became fashionable. This would seem to support the possibility that many pagans were buried in the catacombs. But we know from Tertullian that the Christians in Carthage insisted on a separate cemetery for their dead. The same may have held true in Rome by 200 A.D.

Another explanation for the great number of Christian catacombs in Rome is that the population of the catacombs grew by a form of immigration—namely, by the reburial of Christian remains sent from other parts of the Empire. In other words, some time after burial the bones would be disinterred and placed in a small box of wood or stone, an ossuary, or simply wrapped in cloth and transported to a more desirable location for secondary burial.

Secondary burials were a prominent feature of contemporaneous Jewish customs and have deep roots in the Jewish past. “Being gathered to the fathers,” burial with the ancestors, has been recorded since Genesis. Jacob instructs his sons to carry his body back to the land of Canaan for (final) burial. In the apocryphal Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, specific mention is made of the reburials of Dan and Gad, in one instance after a delay of five years. For the rabbis, reburial in Zion/Israel was desired as a means of atonement and in anticipation of the Resurrection. For Jews of the Diaspora, it was said, tunnels would be provided (as in the catacombs themselves?) for the return to Zion:

“When the dead rise, the Mount of Olives will open and all Israel’s dead will come up out of it, also the righteous who have died in captivity; they will come up through a subterranean passage and come up from under the Mount of Olives.”

(Targum to Song of Songs 8:5)

Thousands of stone and ceramic ossuaries or bone-boxes containing Jewish reburials have been found in the hills surrounding Jerusalem. The discovery of Christian ossuaries used for reburials on the Mount of Olives is solid evidence that Christian communities in Palestine followed this tradition known from Judaism. In the first century of the Church’s existence, Christians had an added incentive to rebury their dead on the hill facing the 029Temple: the imminent Return of Jesus.

If, according to this early theological and eschatological scheme, the Messiah would come again at Jerusalem, why would Christians rebury their dead—and possibly as many as five million people—in tunnels under Rome, the center of pagan worship? Only a catastrophic event could have resulted in such a radical change in Christian thinking that would lead to secondary burials in Rome.

Such an event took place in the second century A.D.—the Second Jewish Revolt (132–135 A.D.) in Judea. When this last prodigious Jewish effort to throw off the Roman yoke failed, Jews were denied entry to Jerusalem and to most other areas of Judea as well. This decree also affected a great many Christians who still considered themselves Jewish—although Christian missionaries were already reaching out more and more to the Gentile population.

As a result of their exile from Zion, the rabbis discouraged calculations about the end of the age when the Messiah would come, heralded by Elijah in Jerusalem. Instead the Jews turned to fulfilling the demands of the Law in the present age. By contrast, the Christians were more concerned with imminent Judgment and the shortness of the time remaining. The apocalyptic visions of the Beast in the Revelation of John were identified with the power of Rome, the city that had dared to call itself eternal and thus mock the sovereignty of God who is alone eternal.

It is difficult for us to imagine the pervasive power of Rome in Late Antiquity. Our times have seen the dissolution of empires, not their creation. That one city on the banks of the Tiber should control such a vast territory from the Euphrates to the Scottish border! On maps the shaded portions can show the extent of the empire at its height in the second century. But to understand its impact on the thinking of people in its day, visit the monuments of the emperor Hadrian. In the first third of the second century, suitable memorials were erected to honor his tour of the empire. So it is that you can walk down the main street of Jerash, Jordan, under the Arch of Hadrian. A similar experience awaits you in Athens, Greece, and Merida, Spain. Finally you can walk the line of Hadrian’s Wall in the north of England, a dividing line between the civilizing administration of the empire in the south and the wild tribes of the north.

The Rome of the great historian Livy, “the city founded in eternity,” would become in the words of a third century Christian, Commodian, a place of everlasting mourning:

“Then the senators shall weep in their bonds; they will curse the chains with which the barbarians load them. … She who boasted of being eternal shall weep for all eternity.”

Jewish sources also speak of the fall of Rome. Rabbi Ishmael, looking toward Rome’s demise, writes:

“Three wars will occur in the latter days one in the forests of Arabia, … another on the sea and one in the great city of Rome which will be more grievous than the other two. … From there the Son of David shall flourish and see the destruction of these and these, and thence he will come to the land of Israel, as it is said,

Who is this that comes from Edom, in crimsoned garments from Bozrah? He that is glorious in his apparel, marching in the greatness of his strength (Isaiah 63:1).

In Roman times, the Jews, both in the Talmud and elsewhere, used “Edom” as a code-word for Rome.

Thus, the Son of David shall come triumphant from Rome, to brandish proudly the faith of his people. This scenario of the End of Days may provide the background to understanding Christian reburials in the catacombs of Rome. With Jerusalem closed to Jews after 135 A.D. and the city renamed by the Romans Aelia Capitolina, Jews and Christians alike had reason to hope fervently for the end of the Empire. While the Jews eventually rejected the cataclysmic solution and turned to a more intense study of the Law, Christians preferred to emphasize the coming Judgment, which would mean the punishment of Rome. Moreover, like Rabbi Ishmael who prophesied the Son of David returning triumphantly from Rome, a substantial segment of the Christian community believed that the Second Coming would occur in Rome. This is clearly reflected in the Acts of Paul and the Acts of Peter, which are biographies of the apostles written in the second century and never canonized in the New Testament. Both books contain an episode known as the Quo Vadis (‘Where are you going?’). The setting is Rome at the time of the hated emperor and tyrant, Nero. In the Petrine version (chapter 35) we see Peter hurrying out of Rome on the Appian Way in an attempt to avoid the Neronian horrors, when he meets Jesus coming toward him. Peter asks, “Where are you going, Lord (Quo vadis, Domine)?” Jesus answers, “I am going into the city to be crucified again.”

Paul reportedly had a similar experience: he saw Jesus walking across the water as his boat sailed toward Italy. But the words of Jesus are the same (Acts of Paul, Chapter 10). Jesus is seen going toward Rome for re-crucifixion.

In contrast, in the Gospel tradition, Jesus tells his disciples of the coming Passion in Jerusalem (Matthew 16:21). The apocryphal literature shifts the location of 031the Passion from Jerusalem to Rome. The significance of this shift in location cannot be underestimated. It bespeaks a change in mentality after the death of Jesus and, 100 years later, after the Second Jewish Revolt.

We learn from the Lives of the Saints that the relics of those saints who were martyred in Asia Minor, Egypt, and elsewhere were brought to Rome for final burial in the third and fourth centuries. They probably hoped to be laid near the first saints buried in Rome who were martyred in Rome on the same day: the apostles Peter and Paul. Excavations at the Vatican, St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, and Saint Sebastian’s have revealed the early custom of Christians’ being buried in close proximity to the supposed graves of these saints.

Outside of Rome, archaeological evidence of secondary Christian burial has been found. In Castelvecchio Subequo, a town 70 miles east of Rome, a small catacomb was discovered that dates to the fourth century. Half-way along the wall of the entrance corridor was a group of small loculi, so-called children’s graves. Examination of these graves showed that they contained only adult bones. Here, then, is proof of reburials by Christians in Italy. This evidence agrees with the literary accounts in the Lives of the Saints of the reburials at Rome from the mid-third century on.

From all these threads, however, the reason for the great number of Christian catacombs at Rome—especially compared to Jewish catacombs—begins to emerge. Spurred by repression and persecution in the Empire, the rabbis and church fathers, each in their own way, restructured their speculations about the End of the Age and the coming of the Messiah. With the Temple destroyed, with the city of Jerusalem by 135 A.D. renamed Aelia Capitolina, and with Jews banned from entering Jerusalem, Jews and Jewish Christians began praying fervently for the fall of Rome. The demise of Rome acquired religious significance—particularly with a view to the advent of the Messiah. Christians believed that those who had died defending their faith against Roman heathenism would be the first to rise in the Resurrection. This conviction placed an obligation on the living to bury the dead in the most favorable site to await the Coming. This meant providing coemetaria, sleeping places, in which the saints could rest until the dawn of the New Age.

The Church at Rome then found itself the custodian of catacombs that not only had to serve the small Christian population of Rome, but also had to receive the relics of the faithful from throughout the Empire. Little wonder that western Christians still turn toward Rome, and not toward Jerusalem, as the primary focus of their pilgrimage. The ancient memory remains, even when clothed in the Baroque splendor of Saint Peter’s basilica in the Vatican.

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Marble Faun, a novel about young artists struggling to learn their craft in 19th century Rome, a group of painters visits the catacomb of Callistus on the old Appian Way. As they wander through the tunnels, their way lit by flickering candles, one of the young women becomes separated from the rest. She was lured away by the Ghost of the Catacombs! The Ghost of the Catacombs, Hawthorne explains, is a “man-demon” who originally “was a [Roman] spy during the persecutions of the early Christians under the Emperor Diocletian” (293–305 A.D.). This man-demon, Memmius, as he […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username