Twice in recent issues of Bible Review, in otherwise excellent articles, Harvey Minkoff has asserted that “Ancient [Hebrew] manuscripts generally did not leave space between words.”a Writing without word divisions is called scriptio continua, or continuous writing.

Ancient Greek was commonly written like that. Stone monuments from Athens and other Greek cities, Greek papyri found in Egypt, classical and biblical manuscripts in Greek all show line after line of letters in unbroken sequences.

Some scholars—and I regret to say Professor Minkoff is among them—have assumed that Hebrew scribes also wrote in scriptio continua. Yet only a superficial look at ancient Hebrew documents is sufficient prove that this is untrue.

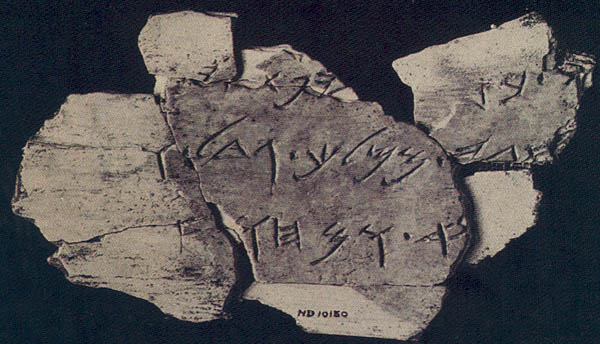

Before the Babylonian Exile (that is, before 586 B.C.), Hebrew was written in a script variously called Old Hebrew, paleo-Hebrew or Phoenician. While this script continued to be used in some circles (the Samaritan alphabet is its descendantb) after the exiles returned, for the most part this script was replaced with the square Aramaic script the exiles brought back with them. Incidentally, the same square script is still used in printing Hebrew today. But even in early Hebrew inscriptions written in the old Hebrew script, a dot was put after each word as a word divider. This word divider can be seen very plainly in the famous Siloam tunnel inscription, an eighth-century B.C. inscription engraved in the wall of the tunnel that the Judahite king Hezekiah dug under the city to bring water into Jerusalem during the siege of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chronicles 32:2–4, 30). The same word separation with the use of dots can be seen in the eighth-century B.C. Nimrud inscription. This fragmentary ivory plaque was found in the ruins of an Assyrian storehouse at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) south of Nineveh, where it was probably taken as booty, perhaps from Samaria. The words that survive are part of a curse on anyone who should destroy the inscription, or possibly the object to which it was affixed.

Brief notes scribbled on potsherds (ostraca), of which scores have come to light, represent the everyday literary products of the early Israelites. Even here, dots as word dividers are usually present, although they are not always easy to see because the ink has run. Sometimes dots as word dividers were even included on ancient Hebrew seals. Moabite and Ammonite scribes in Transjordan used them, too.

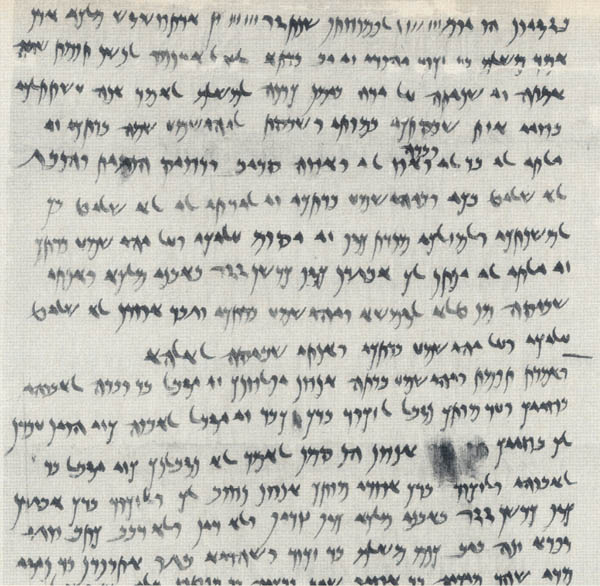

When Jewish scribes adopted the Aramaic script during the Babylonian Exile, they found word division was customary in that writing as well. Instead of a dot, however, scribes left a space between each word, about the width of a narrow letter. The famous fifth-century B.C. Aramaic papyri left by the Jewish community of Elephantine (an island near the first cataract of the Nile) clearly show this word division (see photo, below). The practice applied to letters and legal deeds, as well as to literary works such as the Proverbs of Ahiqar. This Aramaic story and collection of good advice is preserved on pieces of a papyrus scroll found at Elephantine. These pieces are the oldest known example of a book written in a Semitic language on a scroll.

This continued to be the custom for writing Hebrew manuscripts. The Dead Sea Scrolls (230 B.C.–68 A.D.) and the Bar-Kokhba documents (from the time of the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome, 132–135 A.D.) illustrate the method clearly.

Of course scribes did make mistakes, and one of the easiest was to run two words together. A scribe reading his exemplar and copying it phrase by phrase could do that; so could one writing a text from dictation. Many such mistakes were probably corrected long ago. Nevertheless, scholars have detected a few places in the Bible where the Hebrew text is best explained, even today, by making such a correction. The best example is Amos 6:12, which reads in the Hebrew text, “Do horses run upon rocks? Does one plough with oxen?” The Hebrew word for oxen is bqrym. But the singular (ox, bqr) can also be used for the plural. If this is done, the letters ym can be read as a separate word, namely “sea.” By taking the last two letters as a separate word, “sea,” one obtains the sense “oxen the sea.” As the text stands, the first line asks a question to which the expected answer is no; in the second line, read as “Does one plow with oxen?” the reasonable answer is yes. Yet the sense of the verse as a whole expects negative answers to both questions. By separating bqrym into two words, the verse is properly rendered: “Do horses run upon the rocks? Does one plough the sea with oxen?” To both questions one may answer no. It is not hard to see how a copyist ran the two words together, for the resulting form is a perfectly good Hebrew word, “oxen.”

In other cases a scribe might mistakenly split one word into two, especially where the word was unusual. Minkoff provides an example of this at Genesis 49:10, where the Hebrew sylh may be read either as siyloh (Shiloh) or as say loh (tribute to him).

But contrary to common opinion, word division was normal throughout early Hebrew writing and was passed down as good scribal practice in Jewish tradition. Mistakes were made, and often corrected, but mistakes were relatively rare.

Ancient scribes were, of course, well aware how easily mistakes could be made in the course of copying texts by hand. Minkoff correctly describes the customs that tradition followed to insure accuracy. The tenth-century A.D. Aleppo Codex that Minkoff examines displays the highest development of this system.

But the need for accurate copying and the means to achieve it were recognized long before the medieval period. In ancient Egypt and Babylonia, apprentice scribes were taught to reproduce their exemplars exactly. That was as important when copying legal and administrative texts as when copying literary works—or more so. Babylonian literary tablets from the 17th century B.C. onwards sometimes include notes of the number of lines in each column and the total number of lines on a tablet. When the composition was too long to fit on a single tablet, the last line would give the grand total. This is a precursor of the medieval Jewish tradition of counting the letters and verses in books of the Bible, still preserved in the notes at the end of each book in our printed Hebrew Bibles.

If a Babylonian tablet was damaged, the scribe might leave a space in the copy he made from it, with a note in smaller script, “broken” or “newly broken,” even where it seems easy to modern scholars to restore the missing words. Of course, if a scribe did “mend” a passage, his work may be undetectable today.

Tablets made for some ancient collections were checked by a second scribe, then marked “collated.” The copyists often added their own names to the texts they copied, just as they put their names on many legal documents, accepting responsibility for their work. While these customs are best illustrated from the numerous Babylonian cuneiform tablets, they can also be seen in papyri from ancient Egypt.

Although no Hebrew books survive in copies older than the Dead Sea Scrolls (about 2,000 years old), the scrolls illustrate the work of Jewish copyists in that era, exhibiting all the common errors and the steps taken to correct them. Going further back in time, to the Israelite monarchy, the habits of Hebrew scribes can be deduced from writings on stone, pottery and metal found in Israel and neighboring lands. Here, too, concern for accuracy and readability are evident. The beautiful flowing letters of the Siloam tunnel inscription, the epitaphs from Silwan,c the ivory pomegranate from Jerusalemd and the fragmentary ivory plaque from Nimrud clearly show the skill of the scribes. These inscriptions were surely traced in ink by experts, then engraved.

Most texts, however, were written on papyri that have not survived. Evidence for their existence is clear from the hundreds of clay bullae that once sealed them and bear imprints of the papyrus fibers on their backs. Writing was as much a part of Israelite daily life as it was of Babylonian and Egyptian, with the advantage that anyone who wanted to learn could do so more easily, thanks to the simple 22-letter Hebrew alphabet.e

Our Bibles are therefore the legacy of generations of scribes dedicated to copying the sacred text with utmost accuracy. The debt we owe them is incalculable.

Mistakes occurred, but did not pass unnoticed very often. Modern scholars should accuse the ancient scribes of error only when the evidence is very strong. To say an ancient text is wrong may be to deny the only evidence that exists.

Incidentally, mistakes can occur even in printing. Then, however, it appears in every copy. A famous case is the Wicked Bible, an edition of the King James Version issued in London in 1631. The word “not” was accidentally left out of the seventh commandment in Exodus 20:14, so that it read “Thou shalt commit adultery.” The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, ordered the printers to pay a fine of 300 pounds.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See “The Aleppo Codex—Ancient Bible from the Ashes,” BR 07:04, and “The Man who Wasn’t There,” BR 06:06.

See Alan D. Crown, “The Abisha Scroll—3,000 Years Old?” BR 07:05.

Nahman Avigad, “The Epitaph of a Royal Steward from Siloam Village,” Israel Exploration Journal 3 (1953), pp. 137–152.

André Lemaire, “Probable Head of Priestly Scepter from Solomon’s Temple Surfaces in Jerusalem,” BAR 10:01.

See Alan R. Millard, “The Question of Israelite Literacy,” BR 03:03.