I’m looking for a clever aphorism saying that good things sometimes come from something bad. I have in mind the Muslim Waqf’s illegal excavation on the Temple Mount to accommodate a new, larger entrance to the underground Marwani mosque. Truckloads of dirt were dug without regard to archaeological method and then unceremoniously dumped into the Kidron Valley.

When archaeology student Zachi Dvira (Zweig) started rummaging around in the dump, the Israel Antiquities Authority had him arrested for digging without a permit. Zachi’s teacher, prominent Jerusalem archaeologist Gaby Barkay, obtained a permit, and the two of them initiated their famous “sifting project.” With the help of tens of thousands of volunteers, they have been wet-sifting the archaeologically rich dirt—and have discovered thousands of objects from ancient times, including finds from the First and Second Temple periods.a

Wet-sifting, though rare, was not new, but it had never been done before on this scale and with such dramatic results. Initially it was thought that this was largely because the dirt had not been excavated archaeologically. If it had, many of the objects Barkay and Dvira found would have been discovered in the excavation.

However, this led to the thought that the dirt from professionally excavated sites should also be wet-sifted. Important small objects, like seals or seal impressions (bullae) or other inscriptions, might well be missed even in a careful, archaeologically supervised excavation.

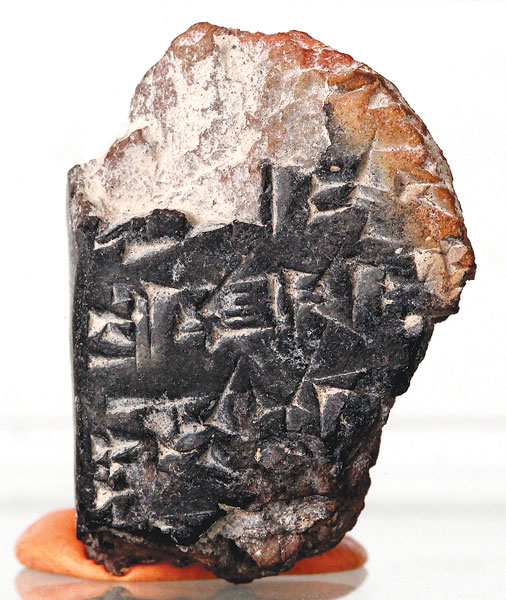

Eilat Mazar, another prominent Jerusalem archaeologist, was digging nearby. She gave Barkay some of the dirt excavated from her site at the southern wall of the Temple Mount to wet-sift. Lo and behold, that is how a tiny cuneiform inscription from the 14th century B.C.E. was discovered, the oldest inscription ever found in Jerusalem.b

This raised an old obsession of mine: the Megiddo dumps.c Several years ago I was visiting the famous ancient mound of Megiddo, where the well-known and distinguished Tel Aviv University archaeologists David Ussishkin and Israel Finkelstein were digging. They pointed out to me three huge dumps, now covered with green, adjacent to the tell. These, they said, were the dumps of excavators who dug here in the early 20th century.

Why not sift these dumps? I thought.

As if providing a persistent drum beat to this idea, more startling finds continue to come from Barkay and Dvira’s wet-sifting project. One involves the pope’s visit to Israel in 2009. In preparation for a Pontifical Mass at a compound of the Franciscan Fathers on the lower slope of the eastern side of the Temple Mount near the Kidron Valley, a contractor was engaged to dig into the terraces of the site. At one point the contractor encountered a refuse pit from the late Second Temple period (first century B.C.E.–first century C.E.). After archaeological intervention by the Israel Antiquities Authority, another refuse pit was discovered below this—from the First Temple Period. The soil was sent to the Barkay-Dvira wet-sifting project.

The results were extraordinary. From the First Temple refuse pit: six clay bullae, one dating as early as the ninth–eighth century B.C., a bone seal, fragments of jar handles with potters’ marks and dozens of figurine fragments. The prize find was a clay bulla inscribed “[G]ibeon, for the king” ([g]b’n/lmlk [Hebrew]), already described for BAR readers in a previous issue.d Known as a “fiscal bulla,” it was part of the tax system in the eighth or early seventh century B.C.E. (In a scholarly article, Barkay dates the bulla to the time of Hezekiah’s son Manasseh; the fiscal bullae replaced the so-called l’melekh handles from Hezekiah’s reign.1) More than 50 of these fiscal bullae are already known, but they all come from the antiquities market. This is the first one recovered from a controlled archaeological project. This one therefore serves to authenticate the others, eliminating any suspicion of forgery. These fiscal bullae were part of the taxation system of different Judahite cities for paying tribute to the Assyrian kings.

This refuse pit is important for another reason. Most archaeological recoveries are from destruction levels; that is, from the very end of an archaeological period. Recoveries from refuse pits, on the other hand, consist of aggregates from the entire period. This refuse pit included generous amounts of pottery dated to the earliest part of Iron Age IIa, the period usually associated with the earliest phase of the United Monarchy, the time of David and Solomon. That we find so little in Jerusalem from the time of David and Solomon may well reflect the fact that it was not followed by a destruction level. When an aggregate refuse pit is analyzed, pottery from the period of David and Solomon appears in abundance.

About 50 feet north of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, archaeologists Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron began excavating layers of soil covering the foundation of the Western Wall beneath Robinson’s Arch. They, too, decided to send all of the removed soil to the Barkay-Dvira wet-sifting project. Again, the results were extraordinary and included a token inscribed “Pure to Yahweh” (dc’/lyh [Hebrew]). (Yahweh is the personal name of the Israelite God.) Scholars are already arguing about whether the token was placed on a Temple offering (as prescribed in the Mishnah) to certify its purity or was used to show that a sufficient payment had been made (in Tyrian shekels) authorizing a libation offering at the Temple, or for some other purpose. But the important point here is that it was found by wet-sifting.e

In my earlier attempt to have the Megiddo dump sifted, I had located a very agreeable, competent gentleman who operated a quarry. He agreed to cooperate on the project. The dirt from the Megiddo dumps would be shoveled onto a moving sieve that would allow everything but large items through. The dump dirt would then drop into a slightly finer sieve that would catch the next smaller objects, and so on. I did not think of wet-sifting at the time.

I took the plan to Ussishkin and Finkelstein. Their first objection was that the mounds of dirt comprising the dump were “monuments” that could not be disturbed. I was never quite sure what this meant. (If necessary, the dumps could be restored after sifting.)

But this objection finally faded in the face of another complicating factor. David Ussishkin insisted that if the dumps were to be searched for items the early excavators missed, they must be excavated stratigraphically—squares, balks and all—as if the dirt were just like original dirt in the tell that had been laid down layer by layer over the centuries.

This would be a monstrously expensive project, however. But I was in no position to argue with my distinguished friend. I agreed to raise enough money for the excavation of a few test squares—to see if digging the dumps was worthwhile.

The job was assigned to a junior archaeologist whose whereabouts is no longer known. He no doubt performed professionally, and I remember he wrote a report that none of us can now find. So at this point, I proceed on pure memory. He found a lot of things but nothing very significant. The most dramatic find was part of a small marble vessel. That was not enough to press the matter further. And that was the end of the project—until the wet-sifting operation of Gaby Barkay and Zachi Dvira.

I raised the matter with David Ussishkin recently at a dinner in Jerusalem. He recognized that my case was stronger now that such dramatic finds had been recently recovered in Barkay and Dvira’s wet-sifting project. Two things made Barkay and Dvira’s finds particularly relevant:

1. They were retrieved even though some of the dirt had been excavated in a competent, professional excavation.

2. One such find from a professional excavation was the cuneiform inscription that came from Eilat Mazar’s dig at the southern wall of the Temple Mount. This inevitably calls to mind one of most significant recoveries from the early Megiddo excavations—part of a cuneiform tablet containing the famous Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamish from the Late Bronze Age (15th–13th centuries B.C.E.). It was retrieved from the Megiddo dump.

This find from the Megiddo dump has always intrigued Ussishkin and Finkelstein. When in 1993 they decided to mount a new dig at Megiddo, this cuneiform tablet was part of the reason. This is what they wrote: “This [cuneiform tablet] provides a tantalizing hint that there may be an archive of cuneiform tablets buried at Megiddo.”f

Part of that cuneiform archive may still be buried in the Megiddo dump waiting to be wet-sifted.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Jerusalem Roundup: The Temple Mount Sifting Project,” BAR 37:02, and Hershel Shanks, “Sifting the Temple Mount Dump,” BAR 31:04.

See Hershel Shanks, “Jerusalem Roundup: Sifting Project Reveals City’s Earliest Writing,” BAR 37:02.

See, for example, Hershel Shanks, Editorial: “Sell the Dump,” BAR 22:06.

See Strata: “The Taxing Work of Archaeology,” BAR 38:02.

For another object found in one of Shukron’s digs by wet-sifting, see Strata: “ ‘Bethlehem’ from IAA Dig Found by Archaeologist IAA Arrested,” BAR 38:05.

Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01

Endnotes

Gabriel Barkay has written a lengthy scholarly article on this bulla: “A Fiscal Bulla from the Slopes of the Temple Mount – Evidence for the Taxation System of the Judean Kingdom.” See http://templemount.wordpress.com/2011/12/28/finds-from-the-first-and-second-temple-period-city-dumps-at-the-eastern-slopes-of-the-temple-mount.