We start with a problem. And some questions. With the exception of the tenth commandment, prohibiting coveting, all the commandments in the Decalogue, as the Ten Commandments are called, appear in similar form elsewhere in the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible). The prohibitions against idolatry and swearing falsely, the commandments to observe the Sabbath and to honor one’s parents, the prohibitions against murder, adultery, theft and bearing false witness—all these appear again and again in the various laws of the Pentateuch. Why then are these commandments gathered together for special treatment? Since they are otherwise imposed on the community of Israel, what function is served by grouping them?

The Decalogue itself appears twice in the Bible, once in Exodus 20:2–17 (verses 2–14 in Hebrew) and again in Deuteronomy 5:6–21 (verses 6–18 in Hebrew), with some slight variations. But separately, the commandments are repeated frequently (see the second sidebar to this article), so several questions naturally arise: Wherein lies the uniqueness of the Decalogue? How did it become the crowning event of the encounter of the God of Israel with the people of Israel? Why is it that precisely this group of commandments is claimed to have been spoken to the people directly by God (Exodus 20:1, 21–22 [verses 18–19 in Hebrew]; Deuteronomy 4:12, 5:4, 22 [verse 21 in Hebrew]), to have been written by God’s finger on the tablets of stone at Sinai (Exodus 31:18, 32:16, 34:1, 28; Deuteronomy 4:13, 5:22 [verse 19 in Hebrew], 9:10) and placed in the Ark of the Covenant (Deuteronomy 10:1–4)?

Was it because of their antiquity? No, neither the content nor the style of the Decalogue proves them to be older than other laws of the Pentateuch. The short commandments— “You shall not murder,“ “You shall not commit adultery,” “You shall not steal”—are not exceptional; similar commandments are to be found in Leviticus 19:11, 13: “You shall not steal, you shall not deceive,… you shall not defraud your neighbor, you shall not commit robbery.” Nor is the variety in the contents of the Decalogue unparalleled; similar compilations are found in Leviticus 19 and in Deuteronomy.

On the other hand, just as there is no proof for the antiquity of the Decalogue, there is nothing to prove it should be dated later.

An important key to the function of the Decalogue lies in the fact that these commandments apply to every individual in Israelite society. This contrasts with the ordinary laws, whose application depends on particular personal or social conditions. For example, sacrifices are conditioned on certain circumstances of the individual (such as vows, sin offerings) or of the community (the Temple service). Other ordinances depend on specific circumstances, such as the laws of purity release of land and liberation of slaves, laws of matrimony, the priestly dues, etc. But every Israelite commits himself or herself not to practice idolatry, not to swear falsely, to observe the Sabbath, to honor parents, not to murder, not to commit adultery not to steal not to bear false witness and not to covet. Moreover everyone is likely to do such things, no matter one’s personal status nor the environment or period in which one lives, and therefore all are warned to abstain.

The Decalogue, for the most part, is formulated in the negative. Even the “positive” commandments—observance of the Sabbath and honoring parents—are in fact prohibitions. The observance of the Sabbath is clarified explicitly by way of prohibition: “Six days you shall work… but the seventh is a Sabbath… you shall not do any work” (Exodus 20:9–10). Similarly, the main object of the commandment to honor one’s parents is to prevent offense or insult, as is seen in the various related laws in other law collections: beating (Exodus 21:15), cursing and disgraceful conduct (Exodus 21:17; Leviticus 20:9; Deuteronomy 27:16), rebellion and disobedience (Deuteronomy 21:18–21). In Leviticus 19 which refers to the Decalogue, the command is indeed formulated in the negative by the opposite of “honor”: “You shall each fear his mother and his father” (Leviticus 19:3).

The inclination toward a negative formulation due to the overall character of this group of commandments. They set forth the basic conditions for inclusion in the community of Israel, conditions transmitted to the people through Moses, who first conveyed God’s word and will to them. These conditions determine what a member of this special divine community is to refrain from doing.

The commandments of the Decalogue are precisely and concisely formulated and contain a typological number—ten—of commands. The original Decalogue can be reconstructed as follows:

1. I, the Lord, am your God, you shall have no other gods beside me.

2. You shall not make for yourself a sculpture image.

3. You shall not swear falsely by the name of Lord your God.

4. Remember to keep the Sabbath day.

5. Honor your father and mother.

6. You shall not murder.

7. You shall not commit adultery.

8. You shall not steal.

9. You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

10. You shall not covet.

With time, these commandments underwent expansion and revision. The complete text of the commandments as they appear in this expanded form in Exodus is printed in the first sidebar to this article. Evidence of this process of expansion and revision can be found in the mostly minor variations between the Decalogue in Exodus and in the repetition in Deuteronomy, which is, as its name implies, a second telling. The process is most conspicuous with respect to the Sabbath. The explanation for the observance of the Sabbath in the Book of Deuteronomy is completely different from that found in the Book of Exodus. In Exodus the explanation is connected with creation: “In six days the Lord created the heaven and earth and sea and all that is therein, and on the seventh day he rested” (Exodus 20:11; compare Genesis 2:1–3). In Deuteronomy the explanation for Sabbath observance is connected to Exodus from Egypt: “The seventh day is a sabbath of the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave.… Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt and the Lord your God freed you” (Deuteronomy 5:14–15). Moreover, in Exodus we are told to “remember” the Sabbath day; in Deuteronomy we are told to “observe” the Sabbath day. The Sabbath in Exodus 20 is conceived as a sacral commemoration intended to dramatize God’s resting on this day, whereas in Deuteronomy 5 the Deuteronomy the observance of the Sabbath is seen as historical recollection, “because you were a slave in the land of Egypt.”a

The commandments of the Decalogue are essentially categorical imperatives—of universal validity, above time and independent of circumstances. No punishment is prescribed; no details or definitions are given. These commandments would hardly satisfy the needs of the legislator, the citizen or the courthouse. What kind of theft is treated in the eighth commandment? What would be a thief’s punishment? Does the commandment prohibiting murder apply to a fellow citizen only or to any human being? What kind of work is prohibited on the Sabbath? The Decalogue does not even imply answers to these questions.

These commandments are not intended as concrete legislation, however, but as a formulation of conditions for membership in the community. Any one who does not observe these commandments excludes herself or himself from the community of the faithful. This is the function of the Decalogue. Although the definitions of laws and punishments are given later in various legal codes, this is not the concern of the Decalogue, which simply sets forth God’s demands of his people. The last commandment (against coveting) is instructive in this regard: This is a command that cannot be enforced, and hence is not punishable, by humans. This command concerns the violation of ethics, which can be punished only by God. In other words, this is not law in the plain sense of the word, but the revelation of God’s postulate—and so are the other commands of the Decalogue.

Indeed, the Ten Commandments are called debarim (words) and not

The “words” of the Decalogue were therefore conceived not as the other laws of the Pentateuch but as divine commands given by revelation, different altogether from the “laws” (

In Hebrew, the commandments are formulated in the second person singular, as if they were directed personally to each and every member of the community. Philo, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher of the first century C.E.,b astutely suggested that an individual might evade a command given to a whole group, “since he takes the multitude as a cover for disobedience”;1 this is not the case with a command addressed to the individual. Philo thus stresses the I-Thou relationship, more recently popularized by Martin Buber.2

The German scholar Albrecht Alt distinguished between casuistic and apodictic forms of biblical legislation. Casuistic law takes the form “if … then.… ” It specifies a sanction for infraction. Apodictic law is simply assertive: “Thou shalt not …” or “Thou shall.…” Apodictic laws appear in other ancient Near Eastern law codes and seem to have originated in a covenantal ritual in which the king stood before his subjects and imposed upon them their duties.

Likewise the Decalogue. It indeed imposes the obligations of the divine King, who appears personally as it were, before his subjects, and imposes upon them his commandments.

It is sometimes claimed that the Decalogue constitutes the epitome of Israelite morality, but there is no basis for such a claim. The Decalogue is not a set of abstract moral rules like those found in other law-corpora such as “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), or “You, too, must defend the stranger” (Deuteronomy 10:19) or “Justice, justice shall you pursue” (Deuteronomy 16:20). The Decalogue is, rather a fundamental list of concrete commands applicable to every Israelite, comprising the essence of God’s demands from his confederates.

The first part of the list expresses the special connection of the people of Israel with their God. This relationship requires connection with their God, an exclusive loyalty (as opposed to the multiple loyalty of idolators), the prohibition of sculptured images and of false swearing by God’s name and the obligation to observe the Sabbath and to honor parents. The second part of the list has a sociomoral character and includes the prohibition of murder, adultery, theft, false witness and coveting of another’s wife and property.

Honoring parents is well suited to serve as a connecting link between the two sets of commandments—those dealing with human-God relations and those dealing with human-human relations—since father and mother belong to a higher authority that must be respected; they are similar to God or a king. An offense against one of these three authorities—God, king or parent—is punishable by death.3 Philo notes that the first five commandments begin with God, the father and maker of all, and end with parents, who copy God’s nature by begetting living persons.4 Elsewhere he says that the commandment to honor parents was placed on the borderline between the two sets of five: It is the last of the first set, in which the most sacred injunctions are given; and it adjoins the second set, which contains the duties of human to human. He explains that the reason for this is that parents by their nature stand on the borderline between the mortal and the immortal.5

The structure of the Decalogue reveals several unifying features: their short form, the typological number ten and the arrangement into two groups (commandments concerning the individual and God and commandments concerning the individual and his or her neighbor). These features testify to the oneness of the unit. A form and structure of this kind enables the commandments to be engraved on stone tablets and to be learned by heart, this intimates that these commandments compose a set of fundamental conditions that every Israelite was obliged to know and learn.

The Decalogue is different from all the other collections of commandments in the Bible: It is distinguished by incorporating a set of concise basic obligations directed at all members of the Israelite community, connected by a special covenant with God. It is a sort of Israelite creed. In this respect it is similar to the Shema‘ (“Hear, O Israel, the Lord [Yahweh] is our God, the Lord [Yahweh] is one”—Deuteronomy 6:4),6 a declaration also composed of an easily remembered verse that contains the epitome of the monotheistic idea and serves as an external sign of identification for monotheistic believers. It is no accident that both the Decalogue and the Shema‘ occur close to one another in Deuteronomy and were read together in the Temple.7

The Decalogue was solemnly uttered by every faithful Israelite as the God of Israel’s fundamental claim on the congregation of Israel, and it became the epitome of the Israelite moral and religious heritage. That is why, among all the biblical laws, the list of commandments contained in the Decalogue came to be regarded as primary and basic in the establishment of the relationship between God and Israel. Only the Decalogue was heard as directly spoken by God, and accordingly it is the Decalogue that serves as the testimony of the relationship between Israel and its God.

At the dawn of Israelite history, the Decalogue was promulgated in its original short form as the foundation document of the Israelite community, written on two stone tablets, later called “the tablets of the covenant” or “tablets of the testimony.” the tablets functioned as a testimony of Israel’s commitment to observe the commandments inscribed upon them. They were placed in the Ark of the Covenant, which, together with the cherubim, symbolized God’s above. The cherubim were considered the throne on which God sat, and the ark was God’s footstool.

Hittite documents contemporary with Moses’ time indicate that nations used to place their covenant documents at their gods’ feet, that is, at the feet of their divine images. This analogy to covenant practices in those days explains Moses’ breaking of the tablets when he saw the children of Israel worshipping the golden calf. For the nations of the ancient Near East (mainly Mesopotamia), the breaking of a tablet meant the cancellation of a commitment. It is thus likely that Moses did not act out of weakness or anger, but with forethought. The violation of the first two commands of the Decalogue (apostasy and the making of sculptured images) by the making of the golden calf (Exodus 32) necessarily entailed the breaking of the tablets on which the commands were inscribed.

The Decalogue was Probably read in the sanctuaries at ceremonies of covenant renewal. The people would commit themselves anew each time, as seen in the usual ancient Near Eastern custom of renewing covenants annually. Psalms 50 and 81 were probably part of these rituals. Both of these psalms relate to the event of the law-giving at Sinai and appear against the background of the Decalogue. The prophets and the poets of the psalms condemn the hypocrisy of the people who do not practice what they preach. For example:

“God the Lord spoke and summoned the world from east to west.… Hear my people.… ‘I am God, your God’.…. And to the wicked, God said: ‘Who are you to recite my laws, and mouth the terms of my covenant, seeing that you spurn my discipline and brush my words [debarai] aside? When you see a thief, you fall in with him, and throw in your lot with adulterers … and yoke your tongue to deceit’” (Psalm 50:1, 7, 16–19).

These rituals took place on the Festival of Shavuoth, the festival of the giving of the Law.

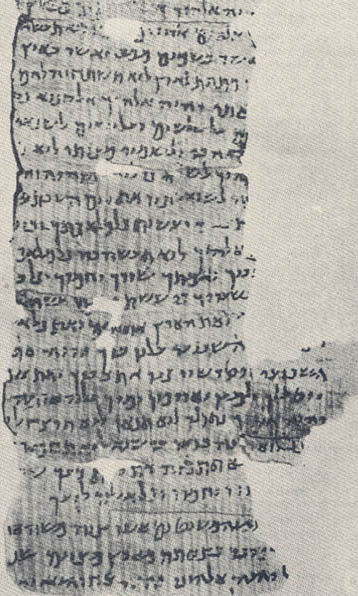

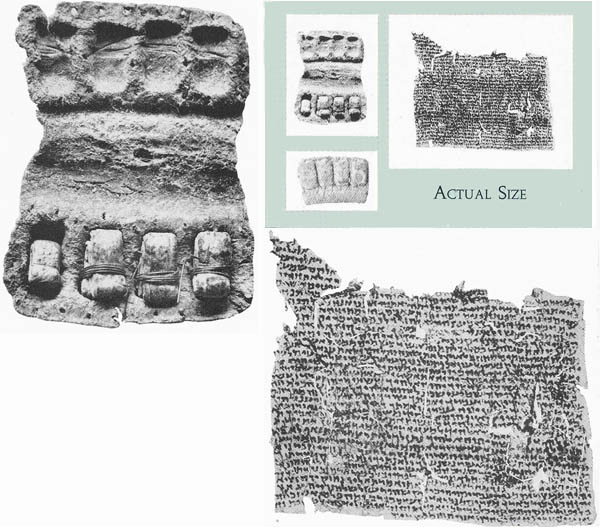

In Second Temple times (sixth century B.C.E.–first century C.E.), the Decalogue was read daily in the Temple, together with the Shema‘ prayer, close to the time of the daily offering (Mishnah, Tamid 5:1). In the 24-line Nash Papyrus (see photo of Nash Papyrus), discovered somewhere in Egypt sometime about the beginning of the 20th century, the Decalogue precedes the Shema‘ passage, a text that reflects a liturgical form. In phylacteries (tefillin) found at Qumran (see photos, above), the Decalogue is also found next to the Shema‘. According to the church father Jerome, this was also the liturgical form in Babylonia.

Originally, the tablets containing the Decalogue constituted a kind of binding foundation-scroll of the Israelite community. With the disappearance of the ark and the tablets of the covenant, the Decalogue was freed from its connection to the concrete symbols to which it had been attached. At festive assemblies and every morning in the sanctuary, the Decalogue was customarily read, and all those present would commit themselves to it by covenant and oath. The recital of the Decalogue every morning was also prevalent among Christians at the beginning of the second century C.E. Pliny the Younger (c. 112 C.E.) tells us about Christians who get up at dawn in order to sing the canons and afterwards commit themselves with an oath (sacramentum) not to steal, not to commit adultery, etc.8 Indeed, the reading of the Decalogue and the Shema‘ proclamation were considered a kind of commitment by oath.9

(For further details and full scholarly apparatus, see Moshe Weinfeld, “The Decalogue: Its Significance, Uniqueness, and Place in Israel’s Tradition,” in Religion and Law: Biblical-Judaic and Islamic Perspectives, ed. Edwin R. Firmage, Bernard G. Weiss and John W. Welch [Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990].)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Leviticus 19 is also based on the Decalogue. The chapter opens with a reference to the fifth, fourth, first and second commandments of the Decalogue: “You shall each fear his mother and his father, and keep my Sabbaths: I the Lord am your God. Do not turn to idols or make molten gods for yourselves: I the Lord am your God” (Leviticus 19:3–4).

The references to the Decalogue are chiastic (that is, in reverse order), as is common with quotations from (and references to) other texts. The author opens with the fifth commandment (honoring parents), continues with the fourth (Sabbath) and concludes with the second (idolatry). Even within the sentence, he changes the order of the components: the object precedes the predicate (not “you shall [each] fear his father and mother,” but “[each] his father and mother shall you fear”; and similarly concerning the Sabbath). Even the order of the objects themselves is interchanged (not “his father and mother,” but “his mother and father”).

In the continuation of Leviticus 19 are found commandments concerning theft, false witness and oaths (Leviticus 19:13, 16) and adultery: “Do not degrade your daughter and make her a harlot” (Leviticus 19:29).

Like the Decalogue, which opens with the self-presentation of God, thus conferring authority to the laws that follow, the commandments of Leviticus 19 similarly open with “I the Lord am your God” (Leviticus 19:2); this formula is repeatedly affixed to various laws of this chapter.

Leviticus 19 fills a gap in the Priestly source of the Pentateuch. In contrast to the Deuteronomic source, which repeats the Decalogue as it appears in the Book of Exodus, the Decalogue is not found in the Priestly legislation, even though it explicitly declares that it transmits the laws and rules given by the Lord “through Moses on Mount Sinai between himself and the Israelite people” (Leviticus 26:46; compare Leviticus 27:34). The absence of any reference to the Decalogue in the Priestly legislation gives the impression that the main point is lacking. Accordingly, Leviticus 19 comes to fill this lack by giving us a “Decalogue” in a reworked and expanded form of its own.

While Leviticus 19 is based on the Decalogue, it is distinctly different. It contains many other laws, most of which are contingent on special circumstances to which they apply. It also includes laws that appeal to conscience, as well as ritual laws.

Endnotes

Compare the curse of God and king in the Naboth story (1 Kings 21) and the curse of father and mother in Exodus 21:15, 17.