What’s a Pleasing Sacrifice?

033

In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel for his part brought of the firstlings of the flock, their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell.

(Genesis 4:3–5)

The concept of sacrifice, and the problems inherent in its practice, greet the reader of the Hebrew Bible almost immediately with the rival offerings of Cain and Abel, the two sons of Adam and Eve.1 Cain prepares a vegetable offering while his brother slaughters and prepares an animal sacrifice. Both of these styles of sacrificial offerings are well known from the ancient world, and each has its appropriate place in later Israelite offerings. However, Cain’s offering is unacceptable to Yahweh (the personal name of the Israelite God) for vague reasons that surely could not have been anticipated by this sacrificing pioneer: “The Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard” (Genesis 4:4b–5a). Seemingly with justification, “Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell” (Genesis 4:5b). The very first instance of sacrificial offering in the Bible, then, is fraught with difficulty.

Why does Yahweh prefer one sacrifice over the other? Was it a procedural matter? Did Cain fail to follow the correct order of operations? Or is the medium the problem? Does God prefer meat? Or was Cain’s attitude or spiritual state somehow inadequate at the time of his offering? This may be implied by Yahweh’s (rhetorical) question to Cain in Genesis 4:7: “If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is lurking at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it.” This admonition to the rebuffed worshiper seems to indicate that correct sacrifice 034requires mastery over certain “sinful” impulses. It is not clear, however, what Cain’s sin might be. Whatever the offense, Yahweh’s (arbitrary?) choice of Abel’s offering over Cain’s leads to horrible consequences, as Cain is driven into a cycle of jealousy and violence that ends with fratricide.

The confusion and uncertainty surrounding this initial sacrifice should alert readers of the Bible to several important issues: There are a wide variety of offering “styles”; the offeror must be sure to present the correct one at the correct time; and the wrong choice can have grave consequences.

The biblical writers make a mighty effort to organize and synthesize the various sacrificial traditions in the Bible, but even the glossy “final form” presented to readers by the final editors known as the Priestly redactors does not settle all of these thorny questions. The never-ending quest to understand the bewildering array of sacrificial offerings in ancient Israel that began with the writers and redactors of the Bible continues today among ritual theorists.

Sacrifice played a central role in religions of the greater ancient world, as it did in the religions of ancient Israel. Notice that I speak of the religions of ancient Israel, rather than of any one monolithic religious system. A careful reading of the biblical traditions, as well as the archaeological record, indicates that religious expression in Israel varied greatly across time, place and social setting. This fact runs counter to the Bible’s explicit claim that the essential features of Israelite religion were revealed en masse at Mount Sinai by the prophet and priest Moses after Israel’s deliverance from Egypt.

As has been shown definitively by source critics since Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918), the Priestly editor(s), working during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E., were responsible for arranging various religious traditions within the Pentateuch into an overarching narrative structure, moving from the creation of the universe through the creation of God’s people to their inheritance of the Promised Land. The amalgam of Priestly legislation in Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers was integrated into the climactic moment of the whole narrative, the revelation of Yahweh’s will at Mount Sinai. By comparing the various legal and ritual ordinances to religious ideas and practices found within individual episodes of the Bible, careful readers will discover that the “system” was not as complete or as early as the text suggests.

Religion in ancient Israel, like most religious systems, was centered around family traditions and practices. The earliest family stories in the saga of ancient Israel, those of Noah and Abraham, depict the father as the leader of the family cult. The family unit, known in Hebrew as the “house of the father” (beth av), 035functioned independently as a self-sustaining religious entity, with the father directing religious matters and serving as the administrator and executor of sacrificial practices. Noah and Abraham offer routine sacrifices, as well as sacrifices meant to celebrate exceptional events in the family life. Gideon, the early Israelite judge, takes a leadership role in purging his family’s shrine of objectionable elements (Judges 8). He also tears down his father’s altar and builds one of his own. In Judges 17–18, a certain Micah is installed as family 036priest when his mother builds a family shrine; later he hires a Levite to officiate for him.

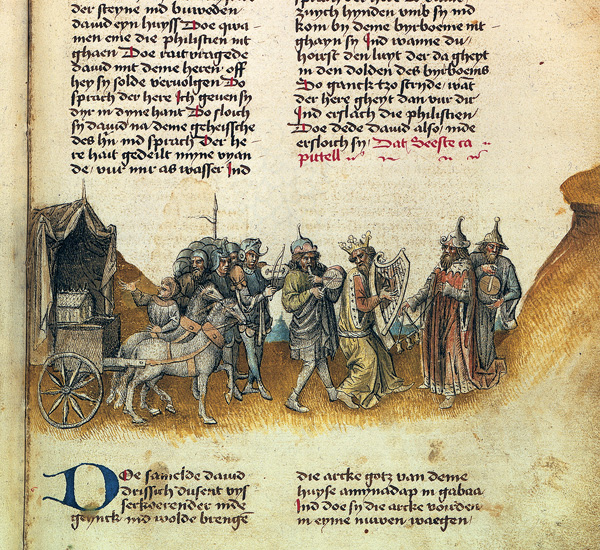

Sacrifice on the family level probably focused on lifecycle events: births and deaths, illnesses and healings, crop harvests, etc. The family would first offer sacrifices to secure God’s favor, and if they got what they wanted they would then commemorate God’s provision with sacrificial meals. Families also gathered once a year for a sacrificial feast, called a zevach. When David decides to flee from Saul’s court, Jonathan, Saul’s son and David’s devoted friend, needs an excuse to explain David’s absence at the royal table during the Feast of the New Moon. David tells Jonathan to tell his father that “David asked [Jonathan’s] permission to run down to his hometown, Bethlehem, for the whole family has its annual sacrifice there” (1 Samuel 20:6). When Saul does raise the issue, Jonathan explains to his father that David asked for permission to attend “a family feast” (zevach mishpachah) in Bethlehem (1 Samuel 20:29). Overall, sacrificial practices in the family tended to revolve around food preparation and feasting.2

As religious life in Israel came to be centralized around the Jerusalem sanctuary, however, certain aspects of these ancient sacrificial practices were brought into the corporate life of the people, although the father 037certainly continued to play a major role in coordinating family worship events. Animal slaughter may have been moved to centralized locations, but the father was probably still in charge. At the very least, families continued to perform rituals at home, such as incense offerings and libations, as we know from the cultic materials, including small incense altars unearthed in family dwellings throughout the Israelite period.

From an early stage in Israel’s existence, associated families would also join together to express their religious devotion. These communities gathered at shared local sanctuaries, which served as an important stimulus for social cohesion and cooperation during uncertain or dangerous times. Archaeologists have shown that Israel developed in the highland areas of Canaan over a long period of time, and in relatively isolated pockets, marked by geographical boundaries. These small communities bonded with each other to promote security and economic efficiency, among other social values. As small family compounds, or clans, coalesced into these tribal associations, corporate expressions of religious identity served to strengthen these social bonds and to address theological needs of the community, such as blessings for regional fertility and public worship of their shared deity. These local shrines were the setting for the ancient agricultural festivals that date to the earliest phases of Israel’s corporate identity—the feasts of Unleavened Bread (Passover; Pesach in Hebrew) in the spring, Weeks (Shavuot) in the summer, and Booths or Tabernacles (Succot) in the autumn.3

In Judges 20–21, the people gather to decide what to do about the men of Gibeah of the Benjaminite tribe who had raped a Levite’s concubine. There, as at other occasional gatherings, the people offer sacrifices as part of their divination of Yahweh’s will: “Then they offered burnt offerings and sacrifices of well-being before the Lord … saying ‘Shall we go out once more to battle against our kinfolk the Benjaminites?’” (Judges 20:26–27).

The chief feature of local religion was the high place (Hebrew, bamah), where the community met to worship its deity. Even though one can certainly describe Yahweh as the national deity of Israel, worship of Yahweh at these high places often incorporated local traditions; for example, inscriptions have been found that speak of Yahweh as “Yahweh of Samaria” or “Yahweh of Teman,” indicating local manifestations of Yahweh.a It is no coincidence that these outlying sanctuaries were the first victims of King Josiah’s centralizing reforms in the late seventh century B.C.E. (of this, more later).

Over time, local associations of highland Canaanite dwellers began to identify themselves in opposition to their lowland Canaanite and Philistine neighbors, and to form a larger identity known as “Israel.”b The extent and power of the United Monarchy of Israel has been vigorously debated by biblical scholars and archaeologists in recent years, but it seems probable that a monarchical state, under the dynastic founder David, united the disparate tribes under a centralized 038administration. This shift would have naturally included the centralization and incorporation of local religious traditions. David brought the Ark, previously the chief religious symbol of the tribes, into Jerusalem (1 Samuel 6), thereby bringing outlying religious institutions into his control, and established himself as the leader of both the political and religious life of unified Israel. From this point on, the relationship between the central cultic establishment (primarily associated with the Jerusalem Temple built by David’s son Solomon) and the monarchy was extremely close. Centralization of cultic institutions was a powerful method to control economic, cultural and religious resources. This was certainly the political motivation behind the religious innovations and reforms of King Hezekiah of Judah in the eighth century B.C.E. and King Josiah of Judah in the seventh century B.C.E.4

Sacrifice in the centralized cult varied depending on the political situation of the monarch on the throne. Hezekiah and Josiah, in their bid for independence from Assyrian dominance, brought all sacrificial activity to Jerusalem, where religious ideas, priestly influence and cultic revenue could be protected and used by the king. The Book of Deuteronomy provides the theological justification for the centralization of worship in Jerusalem, which it identifies as “the place that the Lord your God will choose”:

But you shall seek the place that the Lord your God will choose out of all your tribes as his habitation to put his name there. You shall go there, bring there your burnt offerings and your sacrifices, your tithes and your donations, your votive gifts, your free will offerings, and the firstlings of your herds and flocks. And you shall eat there in the presence of the Lord your God, you and your households together, rejoicing in all the undertakings in which the Lord your God has blessed you.

(Deuteronomy 12:5–7)

In 621 B.C.E., when Josiah’s priests “find” this book of the law in the Temple (2 Kings 22:8), the religious reforms that result coordinate closely with Josiah’s political aspirations as the new David, champion of all Israel (2 Kings 23).

Of primary importance to the development of sacrifice during the monarchical period is the role of the Temple in Jerusalem as the central axis of human-divine relationships. By the time of Hezekiah’s and Josiah’s reforms, all communal festivals, family-oriented sacrificial meals and other forms of sacrifices and offerings in Judah had shifted to the Temple in Jerusalem. At the same time, disparate sacrificial practices and concepts started to be combined and coordinated as part of a holistic system administered by royally appointed priests.

Of course, we should not overlook the vibrant local religious traditions that continued in the north after 039Jeroboam, a former officer of Solomon, snatched the throne of Israel upon Solomon’s death in the late 10th century B.C.E. As king of the northern kingdom, Jeroboam reinvigorated sacrifice at the traditional regional worship centers of Dan and Bethel (1 Kings 12:21–35). These sites, with their cultic calves of gold, continued to be important cultic centers in the north until the mid-eighth century B.C.E. When the prophet Amos invokes the word of Yahweh against the northern kingdom of Israel, after it had been destroyed by the Assyrians, Amos implores his listeners: “Do not seek Bethel” (Amos 5:5). The northern shrines probably never forsook their commitment to Yahweh, but their worship of him was infused with vibrant local traditions.

As we have seen, sacrificial traditions in ancient Israel were formed within a highly complex social and historical matrix. Just as social life was differentiated along economic and status lines, sacrificial traditions adjusted to meet social and theological needs within each context. Also, any one individual would belong concurrently to several interlocking social circles, including the family, the local community and the state or national community. Thus, individuals would necessarily have moved from role to role, participating in religious traditions appropriate to the particular setting. Whereas the family, led by the father, would make small-scale libation and incense offerings, the extended family would also assemble for corporate expressions of penitence and gratitude. Everyone would gather for annual festivals in Jerusalem, in which there would be sacrificial offerings, payment of tithes and other ritual performances.

The ritual legislation in the Pentateuch found its final form only after the Babylonians, who destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple in 587 B.C.E. and sent the Jews into Exile, were themselves defeated by the Persians, and the Persian emperor Cyrus allowed the exiles to return home and rebuild their Temple. In this post-Exilic period, the priests who administered the complex ritual cult of the Temple (now called the Second Temple) assumed great status and authority. There was no longer a monarchy to compete for power.

The Priestly writers of this post-Exilic period were responsible for reorganizing and reshaping much of the ritual legislation found throughout the Pentateuch. But the traditions they draw may be traced back hundreds of years earlier—to premonarchic Israel. Further, the Priestly writers were heavily influenced and inspired in their work by the later, monarchic period reforms of kings Hezekiah and Josiah, who sought to reverse the Israelites’ “backsliding.”

In understanding particular sacrificial traditions, it is thus important to search for earlier roots. For example, Passover is rooted in a premonarchic socio-historical context that was not so centralized or controlled.5 The order of sacrifices given in Leviticus 1–7 (discussed 040below), however, is an artificial Priestly list set in a premonarchic period to satisfy certain Priestly theological commitments.

Leviticus 1–7 describes the various sacrifices and is considered the traditional order of sacrifices. The initial offering was the burnt offering, whose odor was intended to get the deity’s attention, a sort of invocation. The other offerings and sacrifices would follow only after the worship experience had been initiated by the “pleasing odor” of the burnt offering.

Leviticus 1 begins with a discussion of the burnt offering, broken down into three possible variations: a bull from the herd, a male sheep or goat from the flock, or a single bird. In the first two instances, the offerer would bring the animal to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, put his or her hand on the animal to identify with it, and then participate in the slaughtering of the animal. The priest would dash the blood on the sides of the altar, prepare and arrange the carcass carefully, and burn the whole thing up in smoke. The only difference with the bird offering is that it was killed by the priest directly over the altar, evidently so that the small amount of blood could be transferred efficiently to the altar. In every case, the point of the offering is to create “a pleasing odor to the Lord” (Leviticus 1:9, 14, 17).

Next comes the cereal offering, whether in the form of flour, baked cakes or whole grains. The priest would scoop out a token portion to be burned on the altar, and take the rest as “a most holy part,” that is, separated from common use to be consumed in a holy place by the cultic personnel.

Chapter 3 launches into the discussion of the so-called well-being offering (Hebrew, shlamim karbano, the exact meaning of which is uncertain), in which a person would present an animal, either male or female, from among the cattle, sheep or goats. Like the burnt offering, the well-being offering would be slaughtered before the Tent of Meeting, but this time the priest would ritually incinerate the fat all around the internal organs plus the kidneys and part of the liver.6 Then the rest of the meat would supply a festive communal meal.

The placement of the cereal offering between the two sacrificial animal offerings shows the surrogate role played by the cereal offering, the minha, on behalf of poor worshipers.

Leviticus chapters 1–3 form a single unit and together they narrate the process of preparing and offering the main categories of sacrifices. These three aspects of the sacrificial system lay the groundwork for all the ritual legislation to follow. They are each unique and independent but at the same time inextricably connected. The burnt offering and well-being sacrifice are connected because of their common medium, a live animal. On the other hand, the burnt offering is closely connected with the cereal offering since they serve the same purpose for different classes of people. Finally, the cereal offering and the sacrifice of well-being are closely connected since they are not totally burned and therefore provide food for priest and/or worshiper. What seems to be a simple list of offerings is in fact a complex network of ritual theology and practice, encapsulating many of the foundational ideas of the sacrificial system.

041

Whereas the offerings in the first three chapters of Leviticus describe regular offerings with no particular motivation, the two sacrifices described in chapters 4 and 5 outline procedures for dealing with sin and guilt. These offerings address the danger unleashed in the community by impurity and sin. The purification offering (Hebrew, hattat) addresses a situation where a priest, a ruler, or an ordinary member of the community commits an “unintentional” (or inadvertent) sin, for example, accidental contact with a corpse.

Chapter 5 again describes the purification offering, this time outlining how the offering was adjusted for different economic situations. As with the earlier burnt offering, the purification offeror has the choice of a goat, a sheep, two birds (instead of one) or a portion of flour. Unlike the burnt offering, however, these items would be sacrificed and partially burned with the balance going to feed the community and/or the priests.

This chapter also describes the “reparation offering” (Hebrew, ‘asham) for a person who, through some negligence, “misappropriated” some holy item—in other words, failed to deliver a tithe or offering that was due. The reparation offering provides a way for the person to compensate the deity (and the priests!) for the damage. The person would provide a ram to be sacrificed “to make restitution for the holy thing in which he was remiss” (Leviticus 5:16). The remarkable feature is that this offering could be converted into money paid into the sanctuary treasury, in addition to a 20-percent fine. Here we see the Priestly system adapting the purification offering (which was also related to feelings of “guilt”) to a new situation where the offense directly impacts Temple receipts.

In case one’s “misappropriation” of someone else’s property involved defrauding a neighbor (rather than God) by robbery or falsehood, the reparation payments would go to the injured party (plus 20 percent), and the offender would be required to sacrifice a ram as a reparation offering.

This combination of sacrifices undoes damage caused by inadvertent defilement, unintentional negligence in one’s offerings or intentional defrauding of one’s neighbors. The negative effects of such a “sin” is washed away by a purification offering that removes the impurity from the sancta or a reparation offering that pays one’s debts to God or human.

This whole system raises the question of repentance and forgiveness. While the chief concern is purely formal—that is, the priests’ role is to ensure that improper conduct does not defile the holy places and things and thereby open the community to tremendous harm—this is not the whole story. The “sins” of the worshiper disrupt the individual’s feeling of communion with God, or alternatively with the community whose principles have been violated. Sacrifice is a way for the worshiper to confess transgression publicly and to renew one’s relationship with God and neighbor.

Even this list is not exhaustive. For example in Psalm 16 (and in the so-called Thanksgiving Psalms generally) we hear of a thanksgiving offering which is very similar to the well-being offering but which was presented in the context of deliverance from illness or trouble. In Psalm 116 the speaker proclaims that he or she is giving a feast for family and friends in commemoration of God’s act of deliverance.

Patrick Miller has provided a good four-part rubric for understanding the various functions of sacrifice.7

1. Support and welfare. Although the burnt offering was totally consumed, other sacrifices had “by-products” to be allocated in some manner. The fat and certain internal organs were always burned on the altar, but the meat that was left passed either to the offeror (in the case of the sacrifice of well-being) or to the priests. Sacrifices therefore provided support for the sanctuary official (see Leviticus 7:28–36 and 1 Samuel 2:12–17). In addition to the tithes and other “vow” payments, sacrificial products enriched the sanctuary and provided nourishment for its officials. Also, sacrificial offerings provided communal meals that celebrated God’s blessing and provision, most dramatically at the annual festivals.

2. Order and movement. The process of restoring and maintaining holiness and purity was not merely an abstract theological principle. People were dramatically impacted by social conventions governing life and death, illness, crimes and other kinds of social conflict. Sacrifice helped people navigate these momentous and often difficult moments in life, providing a structure whereby they could face the challenges. For example, this clearly defined system allowed lepers to have a safe place to live (outside the “camp”) and provided a mechanism through which they could be reintegrated into communal life.8 Sacrifice was an indispensable tool that allowed people to move safely between different states: pure and impure, holy and common.

3. Flesh and blood. Sacrifice was also a means of enabling the consumption of animal flesh for everyday purposes. Israelites believed that the life of an animal is in the blood, a perfectly natural conclusion. Based on this conviction, sacrifice addressed the problem of flesh and blood in two ways. First, the act of dedicating a sacrificed animal to God acknowledges the principle that “the earth and all that is in it” belongs to God (Deuteronomy 10:14). This assuages the feelings of guilt that arise from taking the life of another living creature. Killing an animal is not for purely selfish reasons but rather part of one’s desire to worship God, and is permitted under God’s command that humans have “stewardship” over all the earth (Genesis 2:26). Also, since blood is the life of the creature it is a very powerful substance that can be used to cleanse and purify things, 044thereby counteracting the power of death that results from decay, illness and sin. Israelites are repeatedly commanded never to consume blood for two reasons: Blood (that is, life) does not belong to us but to God; and it may only be used in appropriate ways in the worship of God.

4. Food and gift. Finally, the Priestly system outlines the precise manner that offerings are to be presented, prepared and incinerated. The text carefully avoids the most ancient function of sacrifice: to provide food for the deity. All societies 045surrounding ancient Israel conceived of sacrifice in this manner, and entire meals were cooked and left in the temple for the god to consume. Ancient myths narrate how people would prepare offerings to favorably impress a deity in order to gain certain benefits. For example, in the Babylonian Flood story the hero Atrahasis successfully averts (for a time) catastrophic plagues that the gods were inflicting on humanity by offering pleasing food to the appropriate deity.9 Several times he is able to assuage the deity responsible for the plague by presenting a baked loaf, saying:

May the flour offering please him,

May he be shamed by the gift and suspend his hand.

The only vestige of this idea in the Bible is the refrain in Leviticus that sacrifices present “a pleasing odor to the Lord.” Also, Leviticus 21:6 says that the priests are responsible for providing the “food of their God.” Beyond this, however, there is little intimation that sacrifice actually provides food for the deity. Indeed Psalm 50:12–15 claims exactly the contrary:

Were I hungry I would not tell you,

for Mine is the world and all it holds.

Do I eat the flesh of bulls,

or drink the blood of he-goats?

Sacrifice a thank offering to God,

and pay your vows to the Most High,

Call upon Me in time of trouble;

I will rescue you, and you shall honor Me.

Sacrifices were considered, along with tithes and vows, “gifts” to Yahweh, a free response to blessings bestowed.

It is important to understand the sacrificial system created by the Priestly writer in Leviticus in light of its component parts. The overall scheme incorporates individual traditions that functioned within the overall structure. Sacrificial practices in the Bible have ancient roots that antedate the final Priestly text by centuries. Traditions such as those around the burnt offering fit the Priestly vision and ordering, but are not explained totally by that system. Stories of family-oriented sacrifice by Noah and Abraham or of regional cultic gatherings contribute to a fuller sense of what these cultic practices meant to people across historical and social boundaries. We cannot assume that a ritual practice always “meant” the same thing at all times. Meaning is always a product of context. As social and political landscapes shifted, ritual meanings adapted as well.

These ancient ritual texts were not written for uninitiated observers, but rather for active participants (usually leaders) of the ritual ceremonies, for whom the explication of underlying meanings would hardly have been necessary. Conceptual categories created by ancient priests, or by modern scholars, can help to sort out these slippery rituals, but they by no means exhaust the meanings embedded in the texts or in the rituals themselves.

The concept of sacrifice, and the problems inherent in its practice, greet the reader of the Hebrew Bible almost immediately with the rival offerings of Cain and Abel, the two sons of Adam and Eve.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

These inscriptions were found on large storage pots at a desert outpost in the Sinai named Kuntillet Ajrud. These texts also mention Yahweh in conjunction with a female divine counterpart, Asherah. See Ze’ev Meshel, “Did Yahweh Have a Consort?” Biblical Archaeology Review, March/April 1979; and Ruth Hestrin, “Understanding Asherah—Exploring Semitic Iconography,” Biblical Archaeology Review, September/October 1991.

The name “Israel” is much older than the time of the United Monarchy, although it is only with the monarchy that we see a whole Israel that unites these component tribes. The term “Israel” first appears in the archaeological record at the end of the 13th century in a victory stele of Egyptian king Merneptah. His defeat of a people named Israel in the Canaanite highlands probably refers to one of the smaller groups that eventually lent its name (and religious traditions) to the larger entity. See Frank J. Yurco, “3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt,” Biblical Archaeology Review, September/October 1990.

Endnotes

Throughout this study, the author has benefited greatly from the excellent work by Patrick D. Miller in The Religion of Ancient Israel, Library of Ancient Israel (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 2000).

Miller, Religion of Ancient Israel, pp. 69–70. In addition to the zevach, Miller mentions the family aspects of the Passover feast as well as the family libations and offerings criticized by the prophet in Jeremiah 7:18.

See, for example, Joshua 3–5 on the spring festival held at Gilgal, Deuteronomy 16 for the summer harvest festival, and Leviticus 23:39–43 for the autumn festival of “booths” or “ingathering.”

This point is also made by the religious reforms and innovations introduced by Ahaz (2 Kings 16:10–18) and Manasseh (2 Kings 21:1–9), who (like Hezekiah and Josiah) brought the cult into line with their political agendas, in this case influenced by their vassal relationship with Assyria. Notice the statement in 2 Kings 16:18 that Ahaz “did this because of the king of Assyria.”

The instructions for the Passover celebration in Exodus 12–13 indicate that lambs should be slaughtered and consumed in diverse family gatherings. Only in Deuteronomy 16 does this celebration become a national festival celebrated in Jerusalem. Notice, for instance, that Deuteronomy does not mention the smearing of blood on the doorpost, which is central to the commemorative observance in Exodus. The differences here have led many to conclude that the Passover was observed among the clans in pre-monarchical Israel and that Deuteronomy reflects a centralizing, reformist vision. This would explain why the reforming Kings Hezekiah and Josiah (2 Kings 23:21–23) lament the fact that the Passover had not been performed “properly” in many years.

There have been many discussions about the particulars of this ritual, and why the priests must burn these particular items. Excellent recent work is found in Mary Douglas, Leviticus as Literature (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999).

Regulations for lepers and other people with such purity issues are spelled out in detail in Leviticus 11–15.

An accessible version of this tale, and others, can be found in Benjamin R. Foster, From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 1995). See Tzvi Abusch, “Gilgamesh: Hero, King, God and Striving Man,” Archaeology Odyssey, July/August 2000; and William H. Steibing, Jr., “A Futile Quest: The Search for Noah’s Ark,” Biblical Archaeology Review, June 1976.