What’s Critical About a Critical Edition of the Bible?

060

Although not widely known, all printed Hebrew Bibles in common use today contain textual difficulties, corruptions and—yes—even errors. Modern translations tend to smooth out difficulties in the original Hebrew. Occasionally some translations, such as the New Jewish Publication Society translation, tell the reader in a footnote that the Hebrew is difficult or that the meaning of Hebrew is unknown, but this only emphasizes that the text is not perfect.

How can there be errors in a text that is venerated as inspired by the word of God and carefully transmitted for centuries?

The answer is that most texts, ancient and modern, that are transmitted from one generation to the next get corrupted in one way or another. For modern compositions, the process of textual transmission from the writing of the original to its final printing is relatively short, thus limiting the possibilities of corruption. But even so, every student of English literature knows, for example, that many mistakes were inserted into editions of James Joyce’s Ulysses as a result of misunderstandings of the author’s corrections in the book’s proof sheets.

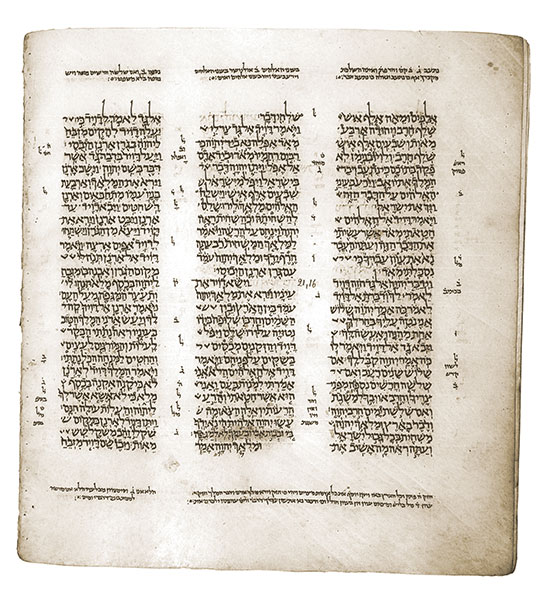

Our earliest complete manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible postdate their composition by more than a thousand years. All of these manuscripts, including the famous Leningrad Codex and the Aleppo Codex, contain errors suffered during the long process of transmission. Scholars have endeavored by various means to correct these errors and ascertain the best possible Hebrew text. Such a text is called a critical edition because it includes a critical apparatus explaining the reasons for the textual decisions.a The current critical edition of the Hebrew Bible that is used by most students and scholars of the Hebrew Bible throughout the world is the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). This edition is now being revised by an international and inter-confessional team of scholars under the auspices of the United Bible Societies. This new edition, called Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ), is being produced 061 in stages, and to date six volumes have appeared.

The Rabbis long ago recognized the possibility of human error when a text was being copied. They warned scribes of the dangers of confusing similar letters like beth and kaph (

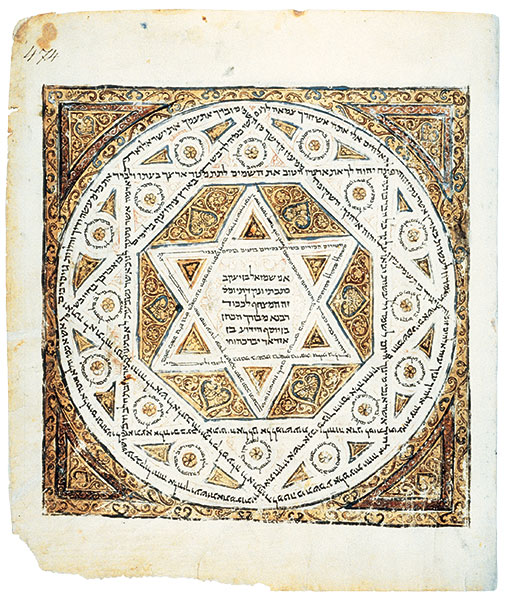

Working largely in Tiberias in the early Middle Ages from around the seventh to the tenth centuries, a group of rabbinic scribes later called Masoretes 062 made valiant efforts to protect the text, safeguarding it by supplementing the text with thousands of notes called masorah written on the top, bottom and sides of manuscripts. Their effort became known as the Masoretic Text and is the standard Jewish text of the Hebrew Bible to this day.b

Yet despite the labors of the Masoretes, the text still contains corruptions, changes and erasures. The reason for this is primarily because the Masoretes made their contribution at a relatively late stage in the development of the Biblical text. At that time the text already contained corruptions. Paradoxically, the Masoretes carefully preserved a text that was already corrupted, and no changes or corrections were permitted.

Why didn’t the Masoretes start from a better text? The answer is that the text the Masoretes 063 chose to work from was itself selected toward the end of the first century. At that time there were many texts circulating (see the Dead Sea Scrolls), none of which was letter perfect. The Dead Sea Scrolls include more than 200 Biblical manuscripts (mostly small scraps), evidencing different types or categories of Hebrew texts, many of which contain scribal corrections or additions written on the manuscripts themselves. The people of Qumran (where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found) who created these texts certainly believed their texts contained the meaningful words of a living God, but their belief was not dependent on any notion of a letter-perfect text.

The variety of Biblical texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls may seem astounding to modern readers. These texts even tend to fall into groups. Some conform in general to the Masoretic Text and are referred to as pre-Masoretic. Others seem to conform more closely to other ancient Biblical text traditions. Hebrew Biblical texts were translated into Greek as early as the third century B.C.E. This ultimately complete Greek text is known as the Septuagint (or LXX) because tradition has it that 70 translators of the Hebrew text came up with exactly the same Greek translation. Some of the Bible texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls provide the Hebrew base text of the Septuagint, comprising another group of Dead Sea Scroll texts of the Bible. Still other Biblical texts from Qumran seem to conform more closely to the pentateuchal text that was preserved by the Samaritans and is known as the Samaritan Pentateuch. And still other Biblical texts from Qumran preserve texts that seem to combine more than one of these traditions.

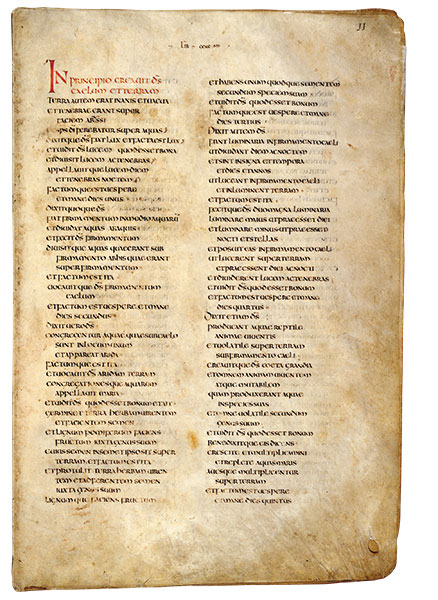

After the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., this array of text-types gradually disappeared in Rabbinic Judaism; the Masoretic type text alone remained, errors and all. But other text-types did not disappear completely. They can be found in the Hebrew texts (what scholars call the Vorlage) underlying translations into Greek, Latin and other languages (i.e., in the Greek, Latin and Syriac Aramaic translations known, respectively, as the Septuagint, the Vulgate and the Peshitta). The Vorlage of these translations differs from the Masoretic Text in many respects, some minor and others quite significant.

A critical Bible translator tries to survey and evaluate all these surviving witnesses to the Hebrew text and ascertain the best possible Hebrew text—and to justify the results in the form of a critical apparatus that is usually found in the bottom margin of each page.

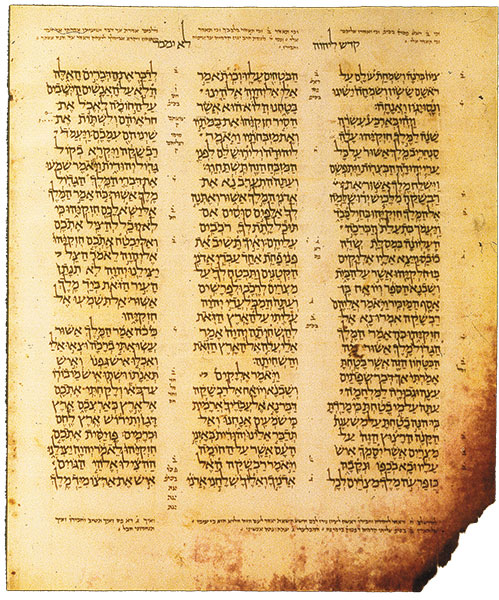

At the present time, three different critical Bible projects in various stages are trying to do this. One, the Oxford University Bible, sponsored by Oxford University Press, is still in its formative stages. Another at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem is the Hebrew University Bible Project (HUBP), which has so far issued three volumes containing the Major Prophets. The third, with which the two authors of this article are associated, is the Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ), which has issued six volumes.

While there are many similarities among these three projects, they differ in conception, scope and editorial control. The HUBP is based on the oldest text of the complete Bible, the Aleppo Codex, dated to about 950 C.E., though unfortunately about one-third of it is missing.c BHQ is based on the Leningrad Codex, which is dated a little later than the Aleppo Codex (to 1008 C.E.). HUBP is a major critical edition that compares not only all Hebrew manuscripts, but also quotations from Rabbinic sources not covered by BHQ.

064

For its part, BHQ is intended to be a handbook, literally to be able to be held in one’s hand.

HUBP operates on a team approach with individual scholars responsible for all its specialized areas under the guidance of an overall editor. BHQ, on the other hand, assigns books to individual authors who are responsible for every aspect of the book, including preparing the masorah, the Hebrew manuscripts and all the other various witnesses. An editor of BHQ, not being an expert in all these subjects, literally has to learn all these areas on the job, so to speak.

BHQ is the latest edition in the Biblia Hebraica series. Biblia Hebraica (BH), Latin for Hebrew Bibles, is a term denoting all printed editions of Bibles in Hebrew, but in a more specific sense it denotes the series of critical Bible editions published in Germany since 1905. The main innovator of this critical Hebrew Bible series was the German Biblical scholar Rudolf Kittel of the University of Leipzig. The first editions of BH appeared in 1905–1906, the second in 1913. Both were published by the Württemberg Bible Institute, a predecessor of the German Bible Society, which had taken upon itself the responsibility of producing scholarly Bibles and has continued with this duty to this day. The base text for these two editions of BH was the Second Rabbinic Bible of Jacob ben Hayyim (1524–1525) which, with improvements over the years, had become the textus receptus for students of the Hebrew Bible for nearly 500 years. However, with the third edition of BH, which commenced publication in 1929, Kittel used as the base text the Leningrad Codex.

The reader will recall that we earlier said that the Masoretes preserved in the Masoretic Text of the tenth century thousands of notes on the text written on the top, bottom and sides of manuscripts, called masorah. A small (or short) masorah is referred to as a Masorah parva (or Mp); a large masorah or Masorah magna is abbreviated Mm. The third edition of BH was completed in 1937 and for the first time included the Masorah parva (Mp) written in the side margins of the Leningrad Codex.

The fourth edition of BH, the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia or BHS, uses the name of its publishing place Stuttgart, rather than the number four. BHS includes the Mp (Masorah parva) from the Leningrad Codex but relegates the Mm (Masorah magna) to a separate volume.

Biblia Hebraica Quinta (Quinta=5; BHQ) is the latest revision of BH. It is being edited by a committee of scholars under the editorship of Adrian Schenker of the University of Fribourg. This project, unlike its predecessors, is international and interconfessional. For the first time in the history of the BH project, Jewish editors are included. Instead of being entirely composed of primarily German Protestant scholars, there are now Catholics as well as Jews among the 22 editors. These scholars come from Switzerland, Italy, Holland, Germany, Ireland, Spain, England, Norway, Finland, France, the United States and Israel.

BHQ includes careful study of color transparencies, the use of a new facsimile edition of the Leningrad Codex and all of the Biblical texts among 065 the Dead Sea Scrolls, as well as new editions of the Septuagint (Göttingen), Vulgate and the Peshitta (Leiden).

The language of discussion is English, not, as in previous editions, Latin or German.

And the sigla that are used are English sigla, not the Gothic letters that often puzzled American students.

The critical apparatus of BHQ also represents a major change. Witnesses from the Septuagint, the Peshitta and the Targum are given in their original language scripts (thus Greek for the Septuagint, Syriac for the Peshitta, etc.) rather than using modern retroversions to an assumed original. Witnesses that agree with the Masoretic text are listed first. The preferred text is usually the Masoretic text, and witnesses that, in the editor’s opinion, do not represent the preferred text are given critical evaluations. Where the Masoretic text is not the preferred text, it too is given an evaluation, and the case is discussed in the accompanying commentary. BHQ also contains separate commentaries for problematic passages.

In-depth study of the Dead Sea Scrolls caused a basic revision in the history of the transmission of the text and hence more respect for the MT than earlier editions had shown, so that BHQ delves deeply into classical Hebrew grammar and syntax and does not resort so easily to emendations in the Hebrew text.

Finally, BHQ includes the Mm (Masorah magna) on the same page where the Masoretic note occurs. By this placement of the Mm, the reader can see quite clearly the relationship of the Mm to the Mp.

This new critical edition is likely to open up for nonexperts exciting new dimensions to the textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible.

Although not widely known, all printed Hebrew Bibles in common use today contain textual difficulties, corruptions and—yes—even errors. Modern translations tend to smooth out difficulties in the original Hebrew. Occasionally some translations, such as the New Jewish Publication Society translation, tell the reader in a footnote that the Hebrew is difficult or that the meaning of Hebrew is unknown, but this only emphasizes that the text is not perfect. How can there be errors in a text that is venerated as inspired by the word of God and carefully transmitted for centuries? The answer is that most texts, ancient […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See “The Art and Science of Textual Criticism,” James A. Sanders’s review of Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, BAR 38:03.

See Marc Brettler, “The Masoretes at Work: A Tradition Preserved,” sidebar to James A. Sanders and Astrid Beck, “The Leningrad Codex: Rediscovering the Oldest Complete Hebrew Bible,” Bible Review 13:04.

See Yosef Ofer, “The Shattered Crown: The Aleppo Codex Sixty Years After the Riots,” BAR 34:05.