Around 1354 B.C.E. a caravan of hundreds of donkeys laden with valuable treasures departed from Washukkani, the capital of the Mittani kingdom in present-day northern Syria. Protected by a formidable military corps of chariots and infantry, the caravan headed through Syria and Palestine to the Egyptian capital of Thebes—a 1,400-mile journey that would take about four months.

As we know from a cuneiform tablet accompanying the caravan, the donkeys carried golden earrings and necklaces, finely carved objects of lapis lazuli, perfume jars, combs and elaborate garments. The main cargo, however, was of the highest possible diplomatic importance: Tadokheba, the daughter of the Mittani king Tushratta, who was to marry the Egyptian pharaoh Amenophis III. In addition to the military escort, the princess’s entourage consisted of 300 servants, most of them female, who saw to her every need. Tadokheba was probably only 13 or 14 years old; her husband-to-be was 48 years old and seriously ill. The Mittani princess was not intended to become queen of Egypt, a position that had been filled for decades by Amenophis III’s principal wife, Queen Tiye. Rather, she would become a privileged member of the pharaoh’s harem—and when Amenophis III died (a mere two years later), she would pass quietly into the harem of his son, Amenophis IV, also known as Akhenaten, the “heretic king.” In the pharaoh’s harem, Tadokheba would meet for the very first time her aunt Kelokheba, who had been sent to marry Amenophis III 20 years earlier.

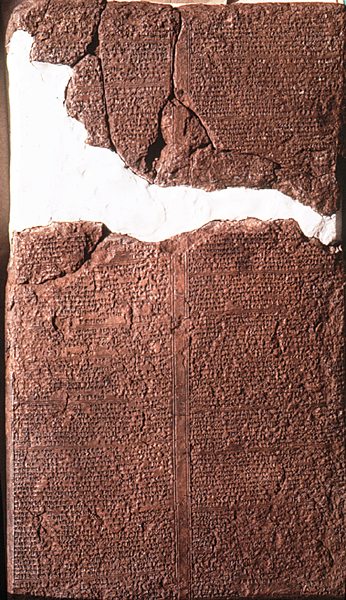

For us moderns, however, the most important object that traveled to Egypt with this caravan was a simple letter. A little over a century ago, in 1887, more than 300 documents from the archives of the Egyptian “foreign office” were unearthed at Tell el-Amarna, the site of the capital city (Akhetaten) founded by Akhenaten. These documents were the correspondence of pharaohs Amenophis III and Akhenaten with various Near Eastern kings. Most of the letters were written in Akkadian, a Semitic language spoken by the Babylonians and Assyrians and used as a diplomatic lingua franca during the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.). Our letter, however, consists of about 500 lines written in the Hurrian language, which was spoken in northern Mesopotamia from the mid-third millennium B.C.E. until at least the late 13th century B.C.E. (see the accompanying article by Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati, “In search of Hurrian Urkesh”). Other letters from Tushratta have been found at Akhetaten, but these are all written in Akkadian. Since these letters dealt with similar topics, however, they provided the main source for the decipherment of the Hurrian language.

Despite its vast distribution across the northern section of the Fertile Crescent, Hurrian was never used for everyday record keeping. Akkadian continued to be used for legal and administrative purposes, not only in the eastern part of the Mittani empire at Nuzi, where one might expect Old Babylonian traditions to have influenced the choice of language, but also in the center of the empire, at Tell Brak, where Mittani documents from the mid-14th century B.C.E. were recently discovered.

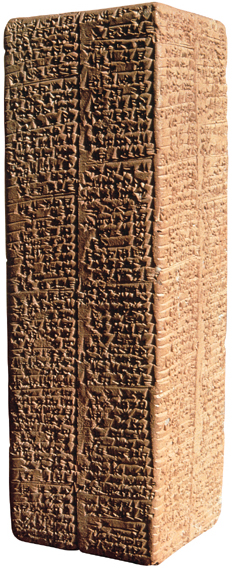

The Hurrian language has a long tradition in Syria. A small copper foundation peg (see the first photo in “City of Myth”), dating to the end of the third millennium B.C.E., is dedicated in Hurrian cuneiform to “Tish-atal, king of Urkesh.” Nevertheless, the Hurrians mainly used Akkadian as the vernacular for deeds and documents. Only in the west did Hurrian become an important and prestigious literary language. Numerous Hurrian tablets and Hittite translations of Hurrian tales have been found in Anatolia. The Hittites looked on northern Syria with admiration and envy; they strove to acquire its wealth and attain its superior civilization. From the late 15th century onwards, Hurrian texts of northern Syrian origin constitute a major portion of the literary corpus copied and studied in the Hittite capital of Hattusha. This is why the greatest number of Hurrian sources come from a place where Hurrian was known only as a foreign language, used mainly for cult and magic.

Toward the end of the third millennium B.C.E. a series of Hurrian city-states arose along the tip of the Fertile Crescent south of the Taurus Mountains. Exactly how a coherent Mittani kingdom developed out of this Hurrian mélange is not known. There may have been a precipitating event, however: the arrival, by migration or invasion, of Indo-Aryan peoples in northern Mesopotamia, several centuries before they conquered northern India in the second half of the second millennium B.C.E. The names of Mittani kings are all Indo-Aryan, and some of the gods worshiped at the Mittani court—Mitra, Varuna, Indra and Nasatya—belong to the Indian branch of the Indo-Aryan languages, which is itself a branch of the Indo-European languages (including, for example, Hittite, Greek, Sanskrit and English).a

It is still a mystery where the speakers of this archaic Indo-Aryan language came from and how they merged with the Hurrians to establish the Mittani kingdom. All this probably happened in the late 17th and 16th centuries B.C.E.—a “dark age” in Mesopotamia that is particularly poor in written material. But it does appear that the Mittani dynasty remained an Indo-Aryan dynasty, a group of kings who made their capital at Washukkani (not yet identified) in what was known in ancient times as the Land of Hurri. This Indo-Aryan dynasty spoke Hurrian and worshiped Hurrian gods (along with some of their own) but maintained their tradition of Indo-Aryan throne names.

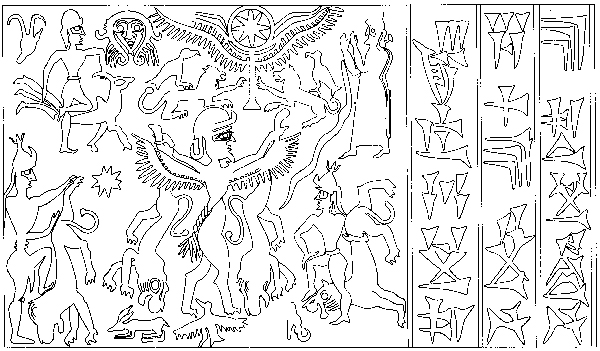

By the early 15th century B.C.E, Mittani had spread westwards, probably as far as the Mediterranean. One bit of evidence is a 16th-century B.C.E. statue from ancient Alalakh (modern Tell Atchana, in western Syria). The statue is inscribed with cuneiform text recounting the travails of one of the city’s kings, Idrimi (see excerpt in the first sidebar to this article). Idrimi’s father, the king of the nearby city of Aleppo, had been assassinated and the family was forced into exile. Idrimi then fled to Canaan, where he lived for a time among some of his countrymen. He later appealed to the “Lord of the Hurrian troops,” the Mittani king Parrattarna, who restored Idrimi to his former splendor—making him king of Alalakh.

The expansion of Mittani power in the north brought the kingdom to the attention of the superpower to the south: Egypt. The first Egyptian reference to Mittani comes during the reign of Pharaoh Amenophis I (1525–1504 B.C.E.), though the northern power does not figure prominently in Egyptian records until the reign of Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.E.). At the Temple of Karnak in Thebes, Thutmose III erected a stela inscribed with the so-called Hymn of Victory, in which the pharaoh recounts his various conquests to the god Amun-Re: “The lands of Mittani are trembling under the fear of thee, / I caused them to see thy majesty as a crocodile, / The lord of fear in the water, who cannot be approached.”1

The dispute between Mittani and Egypt involved the domination of Syria with its vital trade routes, rich agriculture and prosperous luxury goods. The center of gravity of Mittani was northern Mesopotamia, especially the densely populated and fertile lands of the Khabur triangle. Thutmose III prevented the Mittani kingdom from extending its sphere of influence southwards, into territories conquered by early kings of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty after the expulsion of the Hyksos, a dynasty of Asiatic kings who ruled the Nile Delta from 1640 to 1532 B.C.E.

Neither Egypt nor Mittani tried to establish direct administrative control in Syro-Palestine, which was ruled by a heterogeneous group of petty kings. Since competition was strong among these kings, the suzerain—whether Mittani or Egyptian—had little fear of coalitions that might have threatened his position. With some garrison troops and some high ranking supervisors, the essential interests of the overlord were safeguarded. The politicking of the petty kings, even their military moves against one another, could be looked upon with equanimity as long as tributes were paid, equilibrium was maintained and no other great power interfered.

Consequently, it was in the interest of Mittani and Egypt not to interfere in each other’s affairs—or better yet, to establish friendly relations. We do not know whether a formal state treaty was concluded after Thutmose III’s campaigns. In any event, establishing amicable relations with independent powers required new political conventions, which, for Egypt, constituted a radical departure from the traditional royal ideology. Egyptians had long considered their pharaoh the one legitimate universal king; all other self-styled kings were simply “miserable foes” to be subdued. This kind of thinking, clearly, was not conducive to political arrangements involving treaties, pacts and truces. A new convention, however, was supplied by kinship terminology: Sovereign kings began to call each other “brother” and to engage in interdynastic marriages, which served to concretize the kinship relation. But Egyptian pharaohs did not completely concede the perquisites of great-king status. Although they insisted that treaties be sealed by interdynastic marriages confirming the brotherhood of kings, they never agreed to wed an Egyptian princess to an Asiatic king.b

The readiness to conclude such agreements may be explained by the fact that the disputed territory, Syro-Palestine, provided mainly non-essential luxury items, such as olive oil, wine and ivory carvings. (The exception was cedar wood from the Lebanese mountains, a vital building material for the Egyptians.) For the really crucial raw materials, however, such as metals, Egypt and Mittani had their own sources, which lay far beyond the reach of each other. As long as the balance of power remained fairly even, there was no deep-seated conflict between southern and northern nations, only a rivalry for the good things in life.

Prestigious foreign objects—fine gold, elaborate carvings, precious perfumes—had once been acquired by looting. After establishing peace, kings did not simply relinquish their taste for these good things; rather, the process of looting was replaced by a process of the official presentation of gifts. Kings presented their “brothers” with gifts upon exchanging ambassadors, for example, or upon constructing memorials. The most substantial gifts, of course, were royal brides—along with their most impressive dowries.

Thus Tadokheba’s bridal journey to Egypt was part of a tradition of exchanges that had lasted since the 1390s, when Pharaoh Thutmose IV first sealed the peace by marrying a Mittani princess. Tadokheba’s journey, in fact, was the last interdynastic marriage between Egypt and Mittani—and it came only after Tadokheba’s father, King Tushratta, resumed diplomatic relations after a political crisis. While still a child, Tushratta had witnessed the assassination of his older brother, King Artashumara. According to the diplomatic standards of allied kings, each partner was obliged to support the kind of succession preferred by his “brother.” Consequently, Amenophis III had broken ties with Mittani until Tushratta had assumed real power, punished his brother’s assassin and approached the pharaoh to rebuild the states’ traditional political ties.

Tushratta was the last powerful king in a Mittani dynasty that had lasted for about 200 years. The kingdom’s decline occurred as powerful kingdoms to the north, the Hittites, and to the east, the Assyrians, began to exert themselves.

During the floruit of Mittani influence in the 15th century B.C.E., the Hittites could not prevent Mittani from expanding into western Syria and southern Anatolia (modern Cilicia). Toward the end of the 15th century, the Hittite king Tudhaliya I succeeded in conquering Aleppo—which may have prompted the Mittani king Artatama I to negotiate a peace with Pharaoh Thutmose IV, resulting in the first interdynastic marriage.

With the Hittites distracted by troubles on their own northern borders, Aleppo once again recognized the king of Mittani as overlord. Mittani remained more or less undisturbed by its belligerent northern neighbor for the first half of the 14th century B.C.E.

The other country that felt constrained by Mittani was Assyria. Centuries earlier, Assyria had thrived as a center of international trade. Tin from the east and wool products from Babylonia were brought to Ashur and then transported to Anatolia in exchange for precious metals. When the Anatolian trade network broke down, Ashur fell into obscurity and was reduced to a Mittani vassal kingdom, as was its eastern neighbor, Arraphka (modern Kirkuk), a region that included the city of Nuzi. In the 14th century, the Assyrian kings gradually recovered their independence. After the young Tushratta’s brother Artashumara was murdered, the Assyrians took advantage of Mittani weakness by supporting a pretender to the Mittani throne.

At this point, the Hittites and Assyrians formed a coalition to destroy their common enemy: Mittani. The Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (1350–1325 B.C.E.) conquered Mittani holdings west of the Euphrates, while the Assyrians attacked Mittani’s eastern borders. In the end, Tushratta was murdered by one of his sons, a brother or half-brother of princess Tadokheba. The Mittani kingdom, despite the distant friendship of Egypt, could not withstand these shocks. Assyrian troops conquered the Mittani heartland, occupying the important royal cities of Washukkani and Taide.

Wartime coalitions do not usually survive the destruction of the common enemy—and that was true of the marriage of convenience between the Hittites and the Assyrians. When Mittani became a vassal state of Assyria, Suppiluliuma ended his alliance with Assyria and supported Shattiwazza, another of Tushratta’s sons, who became king of a Hittite-dependent Mittani. This, however, was an unstable and weakened kingdom. Shattiwazza’s descendants tried to maintain the great dynastic traditions of the past, but their territory was rent by incursions from the north and east. Toward the end of the 13th century B.C.E., the once formidable Mittani empire disappeared from the political map.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Mitanni kings bore Hurrian names until they actually ascended to the throne; then they assumed their Indo-Aryan names. A number of Hurrian words dealing with the breeding and training of horses are also Indo-Aryan.