Where Is the Tenth Century?

056

056

Every archaeologist thinks his or her site holds the key to any issue that arises. Perhaps that is one reason why the focus was on Megiddo at the sessions titled “Where Is the Tenth Century?” at the Annual Meeting. Archaeologists David Ussishkin and Israel Finkelstein, the first two speakers, are codirectors of the renewed excavations at Megiddo. This is not to deny the importance of Megiddo, however; it is indeed a key site. As Finkelstein has written, “The archaeology of the United Monarchy was born at Megiddo.”1 A second site, whose key significance is more debatable, is Jezreel, where Ussishkin is also codirector (with British archaeologist John Woodhead).

For students of the Bible, the tenth century (B.C., of course) is especially important because that was the time of King David and King Solomon, the short period when ancient Israel was united under a single monarch. (David reigned from about 1000 B.C. to 960; Solomon, his son, from about 960 to 920 B.C.) If we want to know what archaeology can tell us about this period, we have to know which archaeological discoveries—architecture, artifacts and other finds—date from the tenth century.

Until recently, we thought we knew. Now it is a matter of fierce debate.a

Before we get into it, however, we should distinguish this debate from another, quite different discussion—namely the charge by the so-called Biblical minimalists (some call them, pejoratively, Biblical nihilists) that David and Solomon never existed. That discussion is characterized by considerable polemics, which is not true—or at least not as true—of the tenth-century debate. The tenth-century debate is in a sense preliminary to the issues posed by the minimalists: If we are to assess the nature, or even the existence, of the United Monarchy, we must first decide what archaeological materials date to that period. And in the end, the debate with the Biblical minimalists will be affected by the results of the archaeological debate regarding the tenth century. Even Finkelstein, who would move what was thought to be the tenth century down to the ninth century, concedes 057that if the traditional dating prevails against his own views, there will be “no difficulty in demonstrating that in the tenth century there was a strong, well-developed and well-organized state stretching over most of the territory of western Palestine,” and that this state had “an advanced administration and a sophisticated system of management of manpower.”2

As already noted, in the previous consensus about what was the tenth century, Megiddo was at the center of the discussion. The site has seen four major excavations—the first by a German archaeologist, Gotlieb Schumacher, at the beginning of the century, the next by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, then by Yigael Yadin in the 1960s and 1970s, and, finally, the current excavation led by Ussishkin and Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University.

The key stratum is called Stratum VA-IVB (pronounced 5a–4b, but always written with Roman numerals). I wish it had a more easily remembered name, but it doesn’t, so we’re stuck with it. This is the stratum, or occupation layer, previously thought to date to the tenth century. In this stratum, the University of Chicago excavators found a huge, well-built six-chambered gate connected to an important casemate city wall, several palaces and some large tripartite buildings, all of which they attributed to the city of King Solomon.

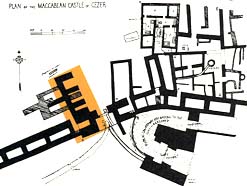

Yadin’s excavation at Megiddo was quite short. Most of the time he spent digging in northern Israel was at the mound of Hazor, where he found a six-chambered gate (three chambers on each side) that was almost identical to the city gate at Megiddo. Yadin knew his Bible well. No one had to call his attention to 1 Kings 9:15, which tells us that Solomon used forced labor to build three sites—Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer. In perhaps the most famous pieces of detective work in the annals of Biblical archaeology, Yadin then went to the report published by R.A.S. Macalister of his excavation of Gezer before World War I. There, in a plan that Macalister had labeled a “Maccabean Castle,” Yadin found what looked like one side of a six-chambered gate identical to the gates at Megiddo and Hazor. At the time of his discovery, Gezer was being re-excavated by a team from Hebrew Union College led by William Dever. On the basis of Yadin’s location of one side of the gate, Dever was able to locate the precise position of the other side of the gate.

There was soon no doubt in anyone’s mind that the six-chambered gates at all three sites—Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer—were the work of King Solomon. As Yadin wrote, they “were in fact built by Solomon’s architects from identical blueprints, with minor changes in each case, made necessary by the terrain.”3

The Bible had provided the key to the identification, as Yadin eagerly recognized: “Our great guide was the Bible; and as an archaeologist I cannot imagine a greater thrill than working with the Bible in one hand and the spade in the other.”4

The Bible also helped the University of Chicago excavators identify some of the tripartite buildings at Megiddo. In the same Biblical passage already referred to (1 Kings 9:15), we are told that Solomon built “cities for chariots and cities for horsemen.” The tripartite buildings were the stables for Solomon’s horses. The Solomonic city of Megiddo was indeed grand, with its impressive six-chambered gateway, casemate city wall, stables and palaces.

Over the years, the complex stratigraphy of Megiddo has been refined—in part by Yadin’s own excavation at Megiddo—and 058several pieces of “Solomonic” Megiddo have fallen away. Yadin himself proved that the stables belonged to a later (ninth century B.C.) stratum. They are King Omri’s stables, not King Solomon’s stables (if they are indeed stables, another matter of debate).b And Ussishkin now contends that the so-called Solomonic gate also dates to the ninth century. Ussishkin and Finkelstein are also taking a new, much bolder step: They are questioning the very date of stratum VA-IVB. They are not simply arguing that the wall or the palaces or the stables should be assigned to a later stratum. They are arguing that Stratum VA-IVB is actually not tenth century, not Solomonic, but a century or so later.

The name of the game is to find a secure date and to work from there to date other things in relationship to the secure date. We have lots of relative dates—they fit into a stratigraphic sequence. Absolute dates are rare. If we can date one level with certainty, or at least relative certainty, we can date strata with the same pottery at other sites to the same date. The chain can be extended this way. A stratum in the second site with a distinctive characteristic can then be used to date a stratum at still another site with this same distinctive characteristic.

Conversely, if the Megiddo gateway is not Solomonic, this calls into question the date of the gates at Hazor and Gezer. In this case, however, even though Ussishkin and Finkelstein date the Megiddo gate to the ninth century B.C., both Amnon Ben-Tor, who is currently re-excavating Hazor, and Dever, who led the Gezer excavation and later returned to the site for a brief excavation of the gate area in the 1980s, stoutly maintain that their gates date to the tenth century, thus reflecting the grandeur of the United Monarchy of Israel.

If the name of the game is to find a secure date from which to reason forward or backward, what are the possibilities? One secure date is the destruction by the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib in the late eighth century B.C. The key site here is Lachish, which was also excavated, or rather re-excavated, by Ussishkin. It was he who clearly—and to virtually everyone’s satisfaction—established that Level III had been destroyed by Sennacherib. This doesn’t help much in straightening out the confused stratigraphy of Megiddo, but it does establish Ussishkin’s reputation as a master stratigraphist.

There is another key destruction layer at Megiddo—the invasion of Shishak. All agree that in 925 B.C. (or within a year or two) 059Pharaoh Sheshonq, called Shishak in the Bible, cut a swath through Judah and Israel. According to the Bible, Shishak’s campaign occurred in the fifth year of the reign of Solomon’s son, Rehoboam. To save Jerusalem from destruction, Rehoboam gave as tribute to Shishak all of the treasures of the Temple and of his palace (1 Kings 14:25–27). At the Egyptian temple of Amon at Karnak, Shishak carved a list of more than 50 sites he claims to have conquered, and presumably destroyed, among them Megiddo.

Archaeologists love destructions. They clearly demarcate one level from another. Sometimes they can be tied to a known historical event. At Megiddo, Stratum VA-IVB was destroyed. Was it destroyed by Shishak in 925 B.C.? If it was, obviously Stratum VA-IVB was a tenth-century city. Until recently it was nearly universally accepted that this stratum was indeed destroyed by Shishak. Ussishkin and Finkelstein now dispute this. According to them, an earlier stratum, Stratum VIA, a less impressive settlement, was the one destroyed by Shishak. Their proposed new dating “strips the United Monarchy of monumental buildings,” in Finkelstein’s words, not only at Megiddo but throughout the kingdom. It throws the period of the United Monarchy into what was previously regarded, archaeologically speaking, as the period of the Judges.

This proposed new dating is hotly contested by one of America’s most prominent and respected field archaeologists, Lawrence Stager of Harvard University, who also appeared on the tenth-century panel organized by BAS at the Annual Meeting. For Stager, Shishak’s invasion can be identified not only at Megiddo but at several other sites. At Megiddo the tenth-century destruction level is Stratum VA-IVB, according to Stager.

As part of his argument, Stager turns to Taanach, another city on Shishak’s conquest list. At Taanach there is no stratum comparable to Megiddo Stratum VIA. If Finkelstein and Ussishkin are right that Shishak destroyed Stratum VIA at Megiddo, then Shishak must have lied about conquering Taanach, as there was no city at Taanach contemporaneous with Megiddo VIA. There is a destruction level at Taanach, however, contemporaneous with Megiddo VA-IVB (as proved by both the pottery and nearly identical cultic assemblages, including altars, cult stands, and even a bowl full of sheep and goat knuckle-bones). Since there is only one stratum at Taanach that can qualify as Shishak’s destruction, the contemporaneous stratum at Megiddo (Stratum VA-IVB) must have also been destroyed by Shishak.

Ussishkin and Finkelstein, on the other hand, rely on Ussishkin’s excavation of nearby Jezreel. Here Ussishkin found a pottery assemblage associated with a monumental fortified enclosure. According to Finkelstein, the pottery is “somewhat similar”5 to the pottery from Stratum VA-IVB at Megiddo. Ussishkin dates the pottery from Jezreel to the ninth century B.C. If it is from the ninth century, so must be the pottery from Megiddo in Stratum VA-IVB. Therefore, Stratum VA-IVB at Megiddo must date to the ninth century.

It is interesting how Ussishkin dates the pottery from Jezreel, as Stager is quick to point out—on the basis of the Bible, of all things! In 2 Kings 9, we are told of the revolt of Jehu against the last king of the Omride dynasty, King Joram, who ruled the northern kingdom of Israel from about 852 to 841 B.C. Jehu killed Joram in battle and proceeded to Jezreel, where Joram’s mother, Jezebel, was waiting. Jezebel painted her eyes with kohl, dressed her hair and went to greet Jehu from a window. At a signal from Jehu, eunuchs threw Jezebel from the window to the pavement below, where her body was devoured by dogs. Ussishkin accepts the historicity of Jehu’s revolt (if not all the details of Jezebel’s death). The fortified enclosure at Jezreel was short-lived, according to Ussishkin, and was probably destroyed by fire. It was built, he says, by King Omri at the beginning of the ninth century; thus, based on the similarity of the pottery, Stratum VA-IVB at Megiddo must also be dated to the ninth century.

Finkelstein says that “Jezreel provides an extremely important chronological clue.”6 Stager, on the other hand, calls it “chronological driftwood.” Ussishkin’s effort to make Jezreel a type site, says Stager, is “a lot of legerdemain … From the very few living surfaces found, in contrast to numerous fills, there is little to instruct us from Jezreel … Jezreel is a leaky boat … I hope [they] will jump overboard before their skiff drifts away. [They] are too valuable as friends and colleagues to be lost at sea.” As Amihai Mazar, of Hebrew University points out, even if the assemblages from Jezreel and Megiddo VA-IVB are “somewhat similar,” this proves little: “We should not expect great changes between the pottery of the second half of the tenth century and that of the mid-ninth century in a limited geopolitical area like the Valley of Jezreel. Thus a general statement about the supposed similarity between the pottery of Megiddo VA-IVB and that of Jezreel does not bear much significance.”7 Finkelstein charges that those who refuse to recognize Stratum VIA at Megiddo as the city Shishak destroyed are motivated by “theological-puritan considerations.” The finds from Stratum VIA, he notes, contain “Canaanite motifs” that explain their “desperate attempt to disconnect [Stratum VIA] from the tenth century [and from Solomonic Megiddo].”

Finkelstein points out that Megiddo’s Stratum VIA contained no Philistine pottery or so-called collar-rim jars, both of which should have been there if it indeed dated to the 11th century B.C. (an 11th-century date being required for this stratum if Stratum VA-IVB is dated to the tenth century).

This is enough to give the flavor of the debate, which is in fact considerably more complicated and extensive than I have presented it here. The principal arguments are presented in technical detail in the articles cited in endnote 5. In addition to the arguments based on pottery chronology, there are other considerations. For example, carbon 14 dates can be obtained for organic samples from stratified contexts. Four samples of carbonized grain from Stratum S-2 at Beth-Shean were recently subjected to carbon 14 testing. Amihai Mazar, the most recent excavator of Beth-Shean, claims Stratum S-2 was an 11th-century settlement contemporaneous with Stratum VIA at Megiddo, the same stratum Ussishkin and Finkelstein claim was destroyed by Shishak in 925 B.C. The results of the carbon 14 tests from Stratum S-2 at Beth Shean clearly support Mazar’s dating. Not a single date tested as tenth century.8 If Stratum S-2 at Beth Shean is 11th century, so must be Stratum VIA at Megiddo. If Stratum VIA at Megiddo is 11th century, then Stratum VA-IVB must be tenth century, as was thought all along. Finkelstein dismisses the carbon 14 evidence out of hand. The reading of the calibration “sometimes allows more than one interpretation … I have no doubt that the accumulating carbon 14 dates will eventually provide us with solid data regarding the 060chronology of the Iron Age strata. But for the time being carbon 14 is far from being a reliable technique for historical periods and is therefore almost meaningless for this discussion.”

Another issue involves the “dense stratigraphy” resulting from lowering what was thought to be tenth century to the ninth century. At Hazor, this results in seven strata in little more than 150 years. This, Mazar tells us, “creates an impossibly brief duration for each of these strata.”9 Finkelstein responds, “Hazor was a border site and hence one would expect many destructions and reoccupations.”

A small part of a stele, originally over 10 feet high, that actually mentions Shishak (Sheshonq) was uncovered in the University of Chicago excavations at Megiddo. Unfortunately, it was not found in a stratified context. But Ussishkin nevertheless uses this as part of his argument that Stratum VA-IVB was not destroyed by Shishak: The stele was erected, he says, to commemorate Shishak’s conquest of Megiddo. But it also tells us that Shishak did not destroy the city; Shishak would not erect a major monument like this in a destroyed city, only in a captured one. Stager responds that if Ussishkin and Finkelstein find another piece of this stele in Megiddo VIA (which Ussishkin and Finkelstein say represents the city destroyed by Shishak), he will concede the argument to them.

It is fair to add that beyond a colleague or two at Tel Aviv University, Ussishkin and Finkelstein have failed to convince their fellow archaeologists. Among those who reject the new chronology proposed by Ussishkin and Finkelstein are Israeli colleagues Amnon Ben-Tor and Amihai Mazar, as well as American colleagues Lawrence Stager, William Dever and Seymour (Sy) Gitin (director of the Albright School of Archaeological Research). Moreover, even Ussishkin and Finkelstein do not claim victory at this point. As Finkelstein has written, he cannot “prove his theory,” adding, however, that “neither would any scholar be able to prove the prevailing view.”10 At the present time, neither side, he says, can claim “a clear-cut verdict.”11 Each side, however, predicts that in time their side will prevail.

Every archaeologist thinks his or her site holds the key to any issue that arises. Perhaps that is one reason why the focus was on Megiddo at the sessions titled “Where Is the Tenth Century?” at the Annual Meeting. Archaeologists David Ussishkin and Israel Finkelstein, the first two speakers, are codirectors of the renewed excavations at Megiddo. This is not to deny the importance of Megiddo, however; it is indeed a key site. As Finkelstein has written, “The archaeology of the United Monarchy was born at Megiddo.”1 A second site, whose key significance is more debatable, is Jezreel, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See “Monarchy at Work? The Evidence of the Three Gates,” BAR 23:04.

See Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01; and Graham I. Davies, “King Solomon’s Stables—Still at Megiddo?” BAR 20:01.

Endnotes

Yigael Yadin, Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible (New York: Random House, 1975), p. 202.

Finkelstein, “Archaeology,” p. 183; and Amihai Mazar, “Iron Age Chronology: A Reply to I. Finkelstein,” Levant 29 (1997), p. 160.

The four test results are (1) 1129–1000 B.C.; (2) 1128–1042 B.C.; (3) 1208–1121 B.C.; (4) 1259–1129 B.C.