Questioning Masada

Where Masada’s Defenders Fell

A garbled passage in Josephus has obscured the location of the mass suicide

032

Prior to Yigael Yadin’s excavations in the 1960s, most of what we knew about Herod the Great’s mountain fortress of Masada came from the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. The story is well known: After the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Temple in 70 C.E., the First Jewish Revolt against Rome was, for all practical purposes, suppressed. However, three fortresses in the Judean wilderness remained outside Roman control: Herodium, Machaerus and Masada. It took the Roman military machine a number of years to attend to these remnants of the revolt. Masada, occupied by 967 Jewish rebels, was the last fortress the Romans attacked. They built numerous camps around the site, amassed thousands of troops, besieged it for three to four years, and, finally, built a ramp and stormed the fortress proper. Yet when the Romans, led by Silva, breached Masada’s walls, they encountered only silence: 960 of the Jews had committed suicide rather than surrender to their enemies.

034

Yadin’s excavations confirmed this account in its broad outlines, but many today question the details given in Josephus’s account and seemingly corroborated by Yadin’s interpretation of the finds. Did the Jews really commit mass suicide? Did the Jewish commander Eleazar Ben Yair actually make the stirring speeches Josephus attributes to him (see “Let Us Leave This World As Free Men”)? Did Yadin really find the lots the Jewish defenders used to select the ten men who would slay everyone else and the one among the ten who would slay the other nine and then himself? Were there really 960 rebels? What happened to the bodies? Did Yadin find some of them, as he claimed (see Whose Bones?)?

I studied Josephus’s account for many years while preparing a book on the episode and its use in modern Israel.1 One sentence of it has always puzzled me. It has led me to think more deeply about what might have happened to the corpses of the Jews. Whether the Jews committed mass suicide or were killed by the Romans, their bodies, I reasoned, had to have been disposed of in some way. This realization led me, in turn, to consider precisely where the mass suicide of the Jews may have occurred. But I am getting ahead of the story.

The sentence from Josephus that has given me so much trouble concerns a palace Herod built at Masada: “He [Herod] built a palace therein at the western ascent; it was within and beneath the walls of the citadel, but inclined to its north side.”2

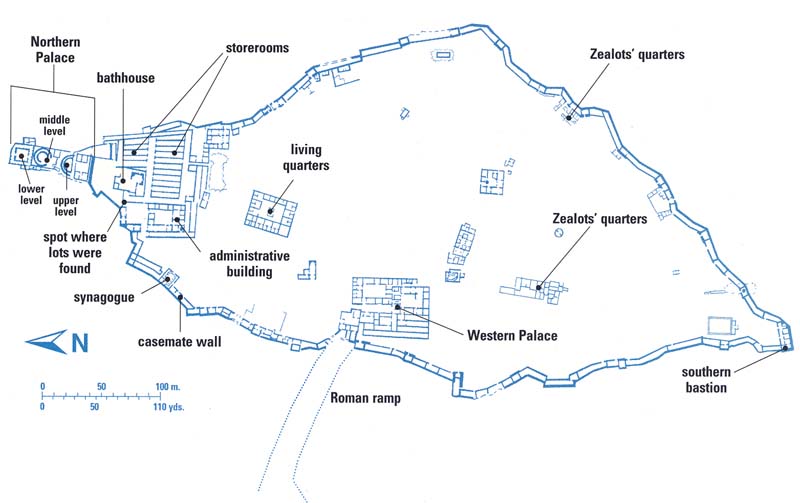

A problem arises here because there are two palaces at Masada, a western palace and a northern palace.

The western palace is the largest structure on the site. It occupies an area of about 36,000 square feet near the point where the western ascent to Masada—the geological formation on which the Romans built their siege ramp—meets the top of the mountain.

The northern palace is the most dramatic and elegant structure on the site. With three levels, it is more a villa than a palace. Its lowest level was supported by huge external walls and columns chiseled into the rock. It had frescoes and a small bath house. The middle level had a small circular structure whose purpose is not entirely clear. The top level contained living quarters and a semicircular veranda that still provides a spectacular view.

To which of these palaces was Josephus referring? 035For many years, scholars thought Josephus meant the western palace since it is located near the western ascent on which the Romans built their ramp. However, this conclusion does not fit the rest of Josephus’s description. The western palace, as Yadin found it, is not “beneath the walls of the citadel” and is certainly not “inclined to its [the site’s] north side.”

For these reasons, Yadin and others concluded that Josephus must have been referring to the northern palace in this passage. The northern palace lay “beneath the walls of the citadel” and was “inclined to its north side.” Moreover, Josephus mentioned “a road dug from the palace, and leading to the very top of the mountain.” This too seems to indicate the northern palace.

There is a problem, however: No western ascent leads to the northern palace. If Josephus’s description is accurate, it cannot refer to this palace either.

From all this, we can draw only one conclusion: Josephus’s sentence simply does not make sense as it stands.

Nor does it make sense that Josephus never seems to mention the western palace at all. Josephus, who is well known for his accurate descriptions, appears to have been quite familiar with Masada. Are we to believe that he simply failed to make any reference to the largest building on the site? This would be especially surprising since the Roman breach of Masada’s wall occurred near this structure.

I believe this sentence from Josephus has been corrupted. Something has been changed or omitted. The 036words that give this away are “a palace … at the western ascent.” This can only be the western palace. Yet the rest of the sentence can only refer to the northern palace. Some text must have been lost in the middle.

I believe that the text stating “He built a palace therein at the western ascent” was originally followed by a description of the western palace and, after that, a description of the northern palace. At some point, the description of the western palace was deleted and the two unrelated sentences were combined, creating an ambiguous text that cannot be parsed.

The various versions of Josephus that survive in manuscript form provide little help in reconstructing this sentence. The standard Greek version with commentary uses the word for “palace,” basileion (literally “place of the king”), in the first part of the sentence, and the word akra, which might indicate a kind of citadel, in the second part of the sentence.3 This use of two different words seems to confirm that the two parts of the sentence refer to two different palaces.

The Greek version of Josephus is based on two principal manuscript groups dating from the 10th to the 12th century. Both textual groups existed as early as the third century. Early translations from the Greek into Latin (fourth and fifth centuries) and Syriac (sixth century) also exist. The omission in this sentence, however, occurs in those texts as well. In short, none of the surviving manuscripts offers a significant alternative reading for this passage.

In 1923 and 1993, Josephus was published in Hebrew translations. Both of these editions incorrectly translate “ascent” (the Greek anabasis) as “descent.” If Josephus had said that Herod built himself a palace “in the western descent,” then, with a little imagination, we might take this as a reference to the northern palace—as if there were a “western descent” leading to it. This is clearly wrong. Apparently, the translators were attempting to make some sense of this critical sentence.

039

Omissions such as the one in this sentence occur accidentally all the time. Sometimes, however, they are intentional. In this case, someone may have wanted readers (contemporary and future) to be unaware of something. But of what? What about the western palace would be worthy of omission? That it was where the Jewish commander Eleazar addressed his people, where the mass suicide occurred and where the Roman soldiers buried the bodies? That is the proposition I would like to explore.

When the final male survivor “perceived that they all were slain,” Josephus tells us, “he set fire to the palace, and with the great force of his hand ran his sword entirely through himself, and fell down dead near to his own relations.” (According to Josephus, a few children and two old women hid themselves and lived to tell the tale.) The implication of this passage is that the collective suicide took place at “the palace.”

Which palace is Josephus referring to? It seems clear that he means the western palace. The lower and middle levels of the northern palace would not have held 960 people. It also would have been hard to assemble everyone on one of the palace levels because the path down to them is difficult to traverse. The western palace, on the other hand, was easily accessible and could have accommodated everyone; it would have been a natural place for the collective suicide. Indeed, even Yadin noted that the western palace was probably the central locale for Masada’s ceremonies and its administration. Also, when Yadin excavated the western palace, he found it had been terribly burnt, which would be in keeping with Josephus’s account.a Furthermore, the word Josephus uses in this sentence for palace is basileion, the same word he used earlier for the palace “at the western ascent,” not akra, the word he used for the palace “beneath the walls.” His very terminology points to the western palace as the place of the suicide and fire.

When the Roman soldiers, probably in full armor, finally broke open the gateway to Masada at the top of the ramp, they entered carefully, expecting to meet resistance. Instead they were greeted only by the sounds, sights and smell of fire. The rebels were dead. The Roman soldiers “attempted to put the fire out, and quickly cutting … a way through it … came within the palace, and so met with the multitude of the slain, but could take no pleasure in the fact, though it were done to their enemies.” In Josephus’s narrative, the Romans do not take long to go through the fire, debris and rubble of the basileion. This also implies that the bodies were discovered in the western palace. Heading north and searching the northern palace would have taken longer; the western palace was near the Romans’ point of entry.

Josephus’s failure to mention the western palace, so central to the entire action, is mysterious. Could someone have tampered with the text to omit whatever description Josephus gave of it? And if so, why?

One plausible answer has to do with the missing bodies. Yadin thought that he had found the skeletons of a few of the slain defenders in a cave on Masada’s southeastern face, but this is open to serious question (see Whose Bones?). In any event, he found fewer than 30 skeletons. So what happened to the rest?

The Romans occupied Masada for nearly 40 years after conquering it; they could not have simply left the dead to rot where they had fallen. They could have thrown the bodies of the slain over the side of the cliff, but I doubt it. I don’t believe the Romans would have wanted to see those bodies at the bottom of the cliff, rotting in the sun and being eaten by animals. Not only would it have been unpleasant and unhealthy, but the Romans apparently had a grudging but understandable respect for their erstwhile enemies. According to Josephus, “Nor could they [the Roman soldiers] do other than wonder at the courage of their [the Jewish rebels’] resolution, and at the immovable contempt of death which so great a number of them had shown, when they went through with such an action.”4

The Romans could have set fire to the bodies, but burning 960 would have been a major undertaking requiring materials hardly available in the desert. They could have buried the bodies in a mass grave, especially if, as indicated above, the Romans had some respect for the dead. But where would they have dug this grave? At the foot of the Roman ramp? Somewhere on Masada’s top? The latter seems more logical. It would have got the bodies out of the way quickly and respectfully. My guess—and it is just a guess—is that the bodies were buried in or close to the western palace, where the Romans had found them.

In the Byzantine period, between the fifth and seventh centuries, monks lived on Masada and built a church northeast of the western palace. Monks usually built their churches and monasteries on sites that had some historical and transcendental significance. Did they come to Masada to build a church where they knew, or guessed, the death scene of Masada had occurred—and perhaps where the bodies were buried?

Finally, did the early Christians delete the information provided in Josephus’s original passage because they did not want later generations of Jews (and others) to make the site a place for Jewish pilgrimage or veneration?

Speculative? Yes. Impossible? No.

I am grateful to Shmuel Gertel for his crucial and significant help in translating original writings and locating sources.

Prior to Yigael Yadin’s excavations in the 1960s, most of what we knew about Herod the Great’s mountain fortress of Masada came from the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. The story is well known: After the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Temple in 70 C.E., the First Jewish Revolt against Rome was, for all practical purposes, suppressed. However, three fortresses in the Judean wilderness remained outside Roman control: Herodium, Machaerus and Masada. It took the Roman military machine a number of years to attend to these remnants of the revolt. Masada, occupied by 967 Jewish rebels, was […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Ehud Netzer, “The Last Days and Hours of Masada,” BAR 17:06.

Endnotes

Benedikt Niese was the German scholar who edited the works of Flavius Josephus in the Teubner series, Flavii Iosephi opera recognovit Benedictus Niese, 7 vols. (Berlin: Weidmannos, 1888–1895). It is considered the authoritative scientific edition of the Greek text of Josephus.