“Ah, Assyria, the rod of my anger” (Isaiah 10:5). This is how generations of readers of the Bible have come to know Assyria, as the terrifying military power that (as the poet Byron put it) “came down like the wolf on the fold” and overthrew Israel and shattered Judah. Despite this reputation—or perhaps because of it—the Assyrians have been the subject of intense fascination in the modern world. Ever since their imposing reliefs and statues were plundered and brought to Europe and America in the 19th century, they have drawn crowds and sold copies of newspapers and magazines.

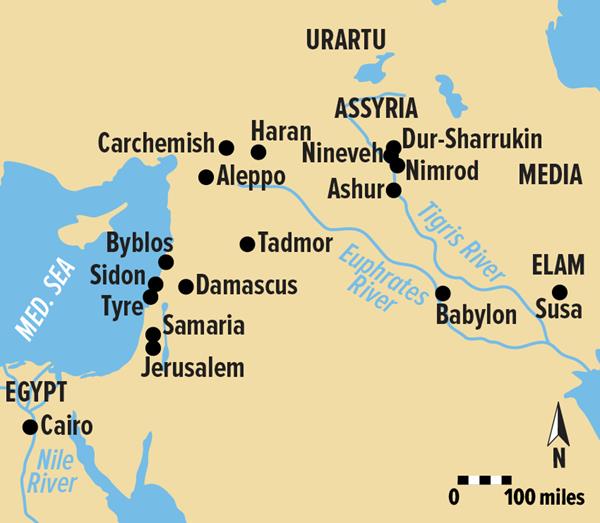

The Assyrians whom the Biblical authors encountered were part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which expanded rapidly across the ancient Near East in the ninth through seventh centuries B.C.E. Its scale had no precedent, but it emerged in a land that already had an ancient history—and, as many nations have, it claimed its roots in distant antiquity.

The Assyrian heartland was northern Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. More than a millennium before the Neo-Assyrians, some of the most powerful kings in the region’s history had ruled not far from the same area. These included Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334–2279 B.C.E.), who was important in propagating the Akkadian language, which became the lingua franca of the ancient Near East for centuries, and Naram-Sin (r. 2254–2218 B.C.E.), who declared himself a god.

About 400 years later, Shamshi-Adad I (r. 1833–1776 B.C.E.) briefly established another “Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia,” which included the later imperial centers of Assur and Nineveh. Already in this period, the Assyrians had an extensive trading network reaching westward into present-day Turkey. Neo-Assyrian rulers sought to connect themselves with these famous predecessors by inserting them into lists of their royal predecessors and by adopting their names.

In the Middle Assyrian period (14th–10th centuries B.C.E.), under rulers such as Ashur-uballit I (r. 1363–1328 B.C.E.) and Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. 1243–1207 B.C.E.), Assyria expanded again, into eastern Syria and Anatolia. From this period, the Middle Assyrian Laws and Palace Decrees shed light on a culture that was militaristic and controlled its court women tightly. Assyria became one of the large regional empires of the Late Bronze Age, but it had a difficult time being acknowledged as a peer by the other contemporary great powers, such as Egypt, Hatti, and Babylonia—partially because Babylonia viewed Assyria as a threat and sought to exclude Assyria through diplomacy. The two Mesopotamian powers continued to struggle against each other over the ensuing two centuries. The reign of Tiglath-pileser I (r. 1115–1077 B.C.E.) was a time of particular Assyrian flourishing.

The Assyrian kings of the late tenth and early ninth centuries campaigned in the west and helped to reestablish regional control through infrastructure. However, it is Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.E.) who is often considered the founder of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. His kingdom reached from the Taurus Mountains in the north to the Euphrates River in the west. He established a new capital city in Kalhu and built it into an impressive city with imperial wealth accumulated from taxes, trade, and the “tribute” payments extracted from vassal nations in exchange for their independence. This “yoke of Assur” was a great burden to smaller client states.

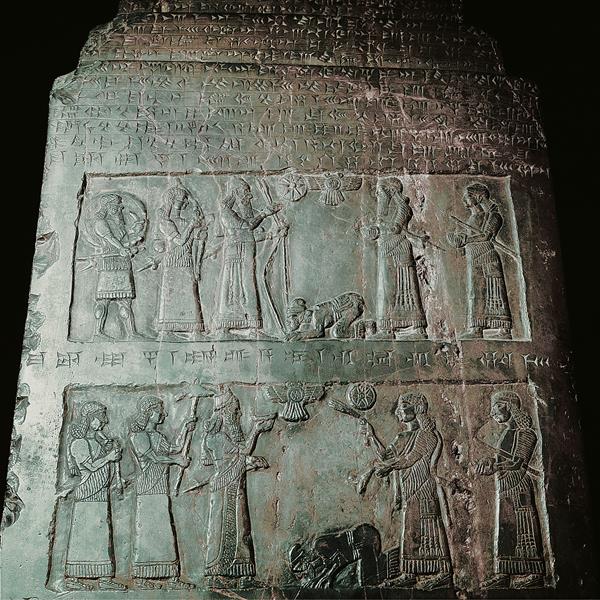

Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 B.C.E.) expanded farther and came into conflict with King Ahab of Israel, who was part of a federation of 12 western kings who had banded together to throw off Assyrian control. As recounted on Shalmaneser’s Kurkh Monolith, Ahab was one of the larger contingents, with 10,000 soldiers and 2,000 chariots. Shalmaneser waged four campaigns against the coalition between 853 and 845 B.C.E. Although the outcomes of these campaigns are not entirely clear, his famous Black Obelisk includes a record of receiving tribute from King Jehu of Israel a few years later, in 841, and even depicts the Judahite contingent.a

Assyria stagnated for much of the next century, struggling with centripetal forces that worked against centralized power. The period saw the rise of Queen Shammuramat, the wife of Shamshi-Adad V (r. 823–811 B.C.E.) and source of the later Greek legends about Semiramis. As mother of the crown prince, she wielded significant influence and was sometimes described as a virtual co-regent with her son.

Tiglath-pileser III (r. 744–727 B.C.E.) brought new energy to Assyria’s ambitions. He quickly resubdued Babylonia to the south and Urartu to the north and campaigned into Syria-Palestine by 738 B.C.E. He took tribute from King Menahem of Israel (r. 746–737 B.C.E.), who taxed every landowner 50 shekels of silver to pay the Assyrians and maintain his power (2 Kings 15:19–20).

The Hebrew prophets frequently condemned Assyria, as well as Israel’s and Judah’s reliance on it (e.g., Hosea 5:13; Hosea 7:11; Hosea 8:9; Micah 5:5–6).

The heavy Assyrian taxation would of course have been controversial, and soon Israel joined an anti-Assyrian coalition of Syro-Palestinian states, akin to Ahab’s. Judah, however, would not participate in this rebellion. Therefore, Israel’s coalition attacked Judah in the Syro-Ephraimitic War in 734 B.C.E. (2 Kings 16:5-9; Isaiah 7), intending to replace Ahaz of Judah with a ruler more sympathetic to their collective goals. It did not work. Judah survived, and Tiglath-pileser wiped out the anti-Assyrian coalition by 731 B.C.E.

At that time, Assyria placed Hoshea (r. 730–722 B.C.E.) on Israel’s throne as a puppet ruler, but even he failed to pay the tribute in 725 B.C.E. and sought the support of Egypt instead. Assyria thus returned to besiege and destroy Samaria, the Israelite capital, in 722–721 B.C.E. The Assyrian emperor Sargon II turned Israel into the province of Samerina (Samaria) and claimed that he deported more than 27,000 Israelites. Surely many others fled southward to Judah as refugees.

Sargon, however, met his end on the battlefield in 705 B.C.E. This uniquely awful fate for an Assyrian king prompted his heir, Sennacherib, to inquire of the gods seeking the reason. It also perhaps brought celebration in Judah (Isaiah 14), and it prompted King Hezekiah to repeat the rebellious pattern of his neighbors by forming a coalition with Sidon, Byblos, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Edom, and Moab and withholding tribute.

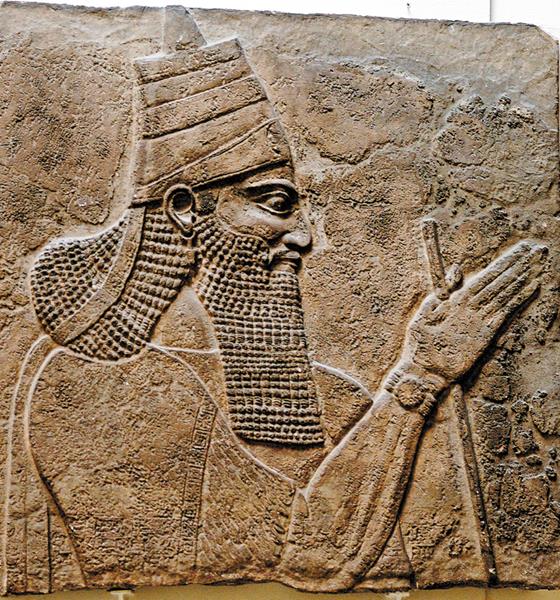

Sennacherib was not free to campaign to the west until 701. When he did, he was seeking vengeance. He claimed to have pillaged 46 Judahite cities and taken more than 200,000 people and animals as spoil. His inscriptions and 2 Kings 18:14–16 agree that Hezekiah paid a heavy tribute but managed, surprisingly, to retain his throne. The events at Jerusalem and the reasons for the outcomes are disputed because of the complex and conflicting assortment of sources: Was it a Cushite intervention? A plague among the Assyrian troops? In any case, it became one of the more celebrated campaigns in ancient Near Eastern history, thanks to the impressive reliefs that Sennacherib proudly made for his palace in Nineveh, depicting his conquest of Judah’s second city, Lachish.b These reliefs now adorn the British Museum.

Sennacherib thus expanded the empire, though he was harassed by rival powers on various fronts and was eventually killed in a palace coup in 681 B.C.E. He was succeeded by Esarhaddon, who skillfully fought off a challenge for the throne from his older brother and showed diplomatic skill in pacifying the rest of the empire.c This allowed him to expand southward, conquering a part of Egypt between 675 and 671. He died of disease while returning there in 669 B.C.E.

Assyria strangely disappears from the Biblical narrative after Sennacherib’s death, but this is not a reflection of political reality. Judah continued to live under Assyrian power as a vassal state; Manasseh’s lengthy reign (698–644 B.C.E.) was possible only through his submission to the empire. Furthermore, Esarhaddon apparently continued moving populations to and from the province of Samerina, based on Ezra 4:2. He also tried to ensure a smoother succession than his had been by making his vassals and his own people swear, in the Vassal Treaties of Esarhaddon, that they would remain loyal to his son Ashurbanipal when he became king. These loyalty oaths are often compared to Biblical covenants, especially that of Deuteronomy.1

Ashurbanipal had a long and seemingly successful reign, extending Assyria’s control over Egypt—though it was never complete, as the Cushites continued to resist. He also suffered civil war at home, as his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, who ruled Babylon, rebelled against him. Elam was a constant thorn in his side; various approaches failed Ashurbanipal until he mounted in 653 a vicious campaign to wipe out the rival nation, sowing salt in its fields and disinterring its dead kings’ bodies. Ezra 4:9–10 suggests that he deported some of the Elamites to Samerina. Ashurbanipal seems to have been complex, however, since he claimed to have advanced scribal training, and his patronage of scholarship allowed the famous library at Nineveh to flourish.

Historians frequently remark upon the mystery of Assyria’s apparently rapid decline. Despite the problems already noted, it was near the height of its power and size in the 640s B.C.E. Ashurbanipal’s death after a long reign, in 631, was followed by succession problems, but those were common. Unfortunately, few Assyrian royal inscriptions survive from the period after 639, and we must rely on the Babylonian chronicles and other Babylonian sources. Led by the Chaldean Nabopolassar, Babylonia regathered itself in the 620s. Joined by the Medes and Scythians, it began to attack Assyrian cities in 615 B.C.E. The Assyrians were taken by surprise in various ways, most significantly by the sudden need to defend their heartland. They seem to have been overextended.

From that point, the collapse was startlingly swift. The capital city of Nineveh fell in 612 B.C.E. after a siege of only three months. Their major cities in ruins, remnants of the Assyrian court and military apparently fled westward, where they survived for a while with Egyptian support. The Babylonian Chronicle, a terse recounting of major events by year, reported Assyrians still fighting in the west in 609. Texts from the Babylonian court—written in the Assyrian dialect at the very end of the seventh century—suggest that the scribal legacy of Nineveh survived for a while, but then the Assyrians are heard from no more.

The Hebrew prophets did not overlook the fall of Assyria. Nahum raised a taunt-song: “Alas, O city of bloodshed, completely deceitful, full of plunder—there was no end to [your] depredations! … There is no relief for your wound, your injury is mortal. All who hear the report about you clap their hands over you. For over whom did your relentless evil not sweep?” (Nahum 3:1, Nahum 3:19, author’s translation; see also Zephaniah 2:13–15). Ezekiel 31–32 would portray Assyria as a “world tree” that once flourished as the envy of the earth but was then cut down; it lists the Assyrians among the empires that “go down to the pit” (Ezekiel 31:16).

Among its achievements, Assyria’s military stands out. Capable of mustering tens of thousands of troops, the army came to specialize in siege warfare and included expert troops drawn from the empire’s numerous territories. Imperial highways and extensive support staff made the military and communications networks more effective. Although the Assyrians had the reputation of being violent, they preferred to use terror-inducing propaganda to achieve their ends—it was more efficient. Their texts and art often portrayed the horrible fates that awaited those who resisted them.

Assyrian religion is often overshadowed by the more prestigious cults of Babylonian cities, but distinctive points emerge. The Assyrians’ high god Assur shared a name with the city and the nation, which was not accidental. He embodied Assyria’s sense of “Manifest Destiny.” Assur was seen as the instigator and guarantor of the nation’s expansion through the agency of the king. In Assyrian tradition, Assur took over Marduk’s role as chief deity in Enuma Elish, the Babylonian myth of creation. Ishtar was important as a goddess of prophecy, and the gods Shamash, Nabu, Enlil, and Ninurta also played significant roles. Ancestors, particularly dead kings, were also seen as divinized powers worthy of supplication. Assyrian rulers avidly practiced ancestor cults as well as numerous other ways of seeking supernatural knowledge.

Despite Assyria’s fearsome reputation in Israel and Judah, its culture was quite influential, including literature, art, and architecture. Assyrian culture was not imposed on them to any great degree, but rather seems to have worked primarily through prestige and emulation, as the story of King Ahaz copying an altar from Damascus indirectly illustrates (2 Kings 16:10–16).

From a literary standpoint, a number of genres of Biblical literature are better understood with a knowledge of Assyrian texts, such as the birth narratives, treaties, and historical records already mentioned. Most distinctive are the Neo-Assyrian prophetic texts. These show certain common phraseology with Biblical prophecies; for example, the Akkadian term for oracles of well-being is shulmu, etymologically related to the Hebrew shalom, “peace.” The compilations of Assyrian prophecies also empirically demonstrate processes that probably mirror the early stages of the formation of Biblical prophetic books. Other Assyrian texts, such as annals, chronicles, and even temple-building accounts, bear comparison with Biblical cognates.

In later Jewish literature, Assyria was one of the nations that represented the prototypical evil foreign empire. It was paired with Egypt in Zechariah 10:10–12 as one of the ends of the earth in a cosmic judgment, and it was “dehistoricized” in a different way in late Biblical narratives such as Jonah and Ezra, in which a Persian king is called “the king of Assyria” (Ezra 6:22; 1 Esdras 7:15). Similarly, in Judith 1:1, Nebuchadnezzar is remembered as a king “who ruled the Assyrians in Nineveh.” By that time, “Assyria” was a general term for the east.

Historians in Classical antiquity were prone to confuse and conflate Assyria with other imperial powers from the east, and eventually Assyria was deemphasized as a paradigmatic empire in favor of Babylon and Rome, so that its cultural and political innovations are often underestimated. For better or worse, Assyria laid the groundwork for those later empires.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. Irit Ziffer, “Portraits of Ancient Israelite Kings?” BAR, 39:05.

2. Philip J. King, “Why Lachish Matters,” BAR, 31:04.

3. Eckart Frahm, “‘And His Brothers Were Jealous of Him’: Surprising Parallels Between Joseph and King Esarhaddon of Assyria,” BAR, 42:03.