Armageddon—the name is synonymous with apocalypse, Judgment Day and end-time. As the site of the cataclysmic battle between the forces of good and the forces of evil, Armageddon has gripped the imagination of Christians ever since John wrote the New Testament’s Book of Revelation at the close of the first century A.D.1

The very word “Armageddon” is evocative, powerful, even frightening. Yet it is simply a place-name. Armageddon comes from Greek ‘

But why did John choose this relatively remote city as his battlefield? Why not Jerusalem, or Rome, or even Athens? The answer, as we will see, hinges on Megiddo’s strategic location on the edge of empires, as well as its role in the downfall of the Davidic monarchy, as described in the Hebrew Bible.

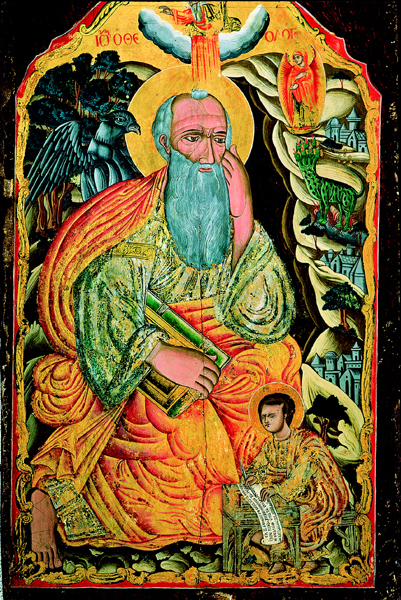

The opening chapter of the Book of Revelation tells us that John wrote the text while exiled on Patmos, a small rocky island in the Aegean Sea. Here, “one like the Son of Man” appeared to John in a vision and commanded him to “write what you have seen, what is, and what is to take place after this” (Revelation 1:19). The powerful and poetic text of Revelation describes in vivid detail John’s visions of the world to come. Tradition identifies the John of Revelation with the apostle and the evangelist of the references indicate that the Book of Revelation was probably written in the late first century A.D., during the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (81–96 A.D.).2

Despite the dizzying array of symbols, numbers, psychedelic images and dream sequences found in the Book of Revelation, the events leading up to Armageddon, the battle itself and the ensuing events are set out in a fairly straightforward manner. Details about the events that will immediately precede the battle of Armageddon are given in Revelation 6–16:15. These include great earthquakes (6:12–17, 8:5, 11:13, 19); thunder and lightning (8:5, 11:19); hail and great fires (8:7, 16:8–9); a comet or asteroid (8:10–11); partial eclipses, both solar and lunar (8:12); a plague of locusts (9:3–11); the death of one-third of all humankind, with blood flowing for 200 miles (9:15, 14:20); the arrival of 200 million cavalry troops (9:16); a plague of foul and painful sores (16:2); the death of every living thing in the sea (16:3); the transformation of all rivers and springs into blood (16:4); total darkness (16:10); and the drying up of the great Euphrates River in order to prepare the way for kings from the east (16:12).

Only then, John records, will the combatants assemble for the catastrophic battle between the Antichrist and the Messiah. It is at this point that Armageddon is mentioned for the first and only time in the Bible. According to John, the forces of evil will be summoned to Armageddon by three foul spirits, shaped like frogs.a John records:

And I saw three foul spirits like frogs coming from the mouth of the dragon, from the mouth of the beast, and from the mouth of the false prophet. These are demonic spirits, performing signs, who go abroad to the kings of the whole world, to assemble them for battle on the great day of God the Almighty…And they assembled them at the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon.

Revelation 16:13–16

In this manner, the “kings of the whole world” and their armies are called to war by the evil spirits. The human armies will therefore be battling on the side of evil rather than the side of good.3 They will be fighting for the Antichrist, also called the beast, and against the new Messiah.

The army of the good, according to John, is led by a brilliant, dramatic figure on a white horse:

Then I saw heaven opened, and there was a white horse! Its rider is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war. His eyes are like a flame of fire, and on his head are many diadems; and he has a name inscribed that no one knows but himself. He is clothed in a robe dipped in blood, and his name is called The Word of God. And the armies of heaven, wearing fine linen, white and pure, were following him on white horses.

Revelation 19:11–14

The rider on the white horse is prepared to smite his enemies:

From his [the rider’s] mouth comes a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron; he will tread the wine press of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has a name inscribed, “King of kings and Lord of lords.”

Revelation 19:15–16

The rider is, therefore, the Messiah himself.

After both armies are introduced, the battle begins:

Then I [John] saw the beast and the kings of the earth with their armies gathered to make war against the rider on the horse and against his army. And the beast was captured, and with it the false prophet…These two were thrown alive into the lake of fire that burns with sulfur. And the rest were killed by the sword of the rider on the horse, the sword that came from his mouth…Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven, holding in his hand the key to the bottomless pit and a great chain. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, and threw him into the pit, and locked and sealed it over him, so that he would deceive the nations no more, until the thousand years were ended. After that he must be let out for a little while.

Revelation 19:19–20:3

Thus, the forces of good defeat the forces of evil.

The passage that follows (Revelation 20:4–6) describes the battle’s aftermath, in which all human martyrs will be restored to life and reign with Christ for one thousand years.b When that period expires, Satan will be released from prison and will yet again deceive the nations “at the four corners of the earth” by leading them one last time into battle.4 Under Satan’s command, the deceived nations will march against Jerusalem and the army of the saints, only to be defeated once more in the last conflict between good and evil (Revelation 20:7–10). At this point, Judgment Day will take place: The dead will be resurrected and then judged “according to their works”—according to what they have done (20:11–15)—and a new era will begin, with “a new heaven and a new earth” (21:1–8).

Thus, contrary to popular belief, the battle scheduled to be fought at Armageddon is not, in fact, destined to be the last battle ever fought, but rather the penultimate one, taking place during the first phase of the final conflict. The second battle, the one to be fought at Jerusalem after an intervening thousand-year period of peace, will be the ultimate battle in the conflict between good and evil.5

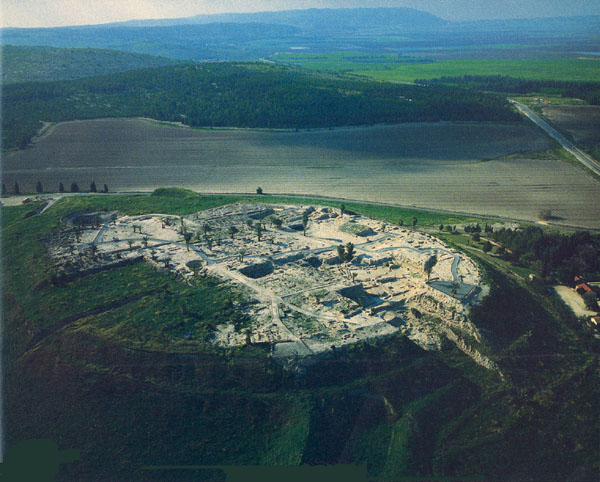

Some scholars object to identifying the site of the first battle, Armageddon (the Mount of Megiddo), with Megiddo, claiming that there is no true mountain at Megiddo.6 They propose that the reference therefore must be to another mountain in the Jezreel Valley—such as Mount Carmel in the west, or perhaps Mount Gilboa or Mount Tabor in the east. Others suggest instead that Armageddon should be translated as “Mount of Assembly” (from the Hebrew Har Mo’ed; cf. Isaiah 14:13) rather than “Mount of Megiddo”; thus the reference would be to Mount Zion in Jerusalem rather than to Megiddo.7 But the corruption of “Har Megiddon” to “Har-mageddon” and thence to “Armageddon” is readily seen in early versions of the New Testament, where the Greek is frequently spelled with an aspirate (‘) or H at the beginning of the word: ‘

Further, Megiddo is indeed a mount, albeit a man-made one, formed on a hill from the remains of the successive cities built at the site in ancient times.c By the Iron Age, in the early first millennium B.C., the mound was about 70 feet high. As each generation continued to rebuild on the remains of earlier cities, the mound, or tell, grew, so in the Hellenistic and Roman periods it would have been even higher. (It is a bit shorter today because of excavations.) Further, the valley floor surrounding Megiddo was lower at that time than it is now; over the past two thousand years, flooding and related events have deposited as much as 10 feet of soil and debris here.9 At any rate, there is no doubt that Megiddo would certainly have been seen as a mount in John’s day, and thus there is no problem in interpreting the word “Armageddon” as coming from “Har Megiddon” and as referring to Megiddo and, by extension, the surrounding Jezreel Valley.

It is this 70-foot mound—and the succession of cities that were built, destroyed and rebuilt here—that provides our first clue to understanding why John set the initial phase of the end-time battle at Megiddo. For John would have recognized Megiddo and the surrounding Jezreel Valley as having been host to a parade of gory military conflicts throughout history.

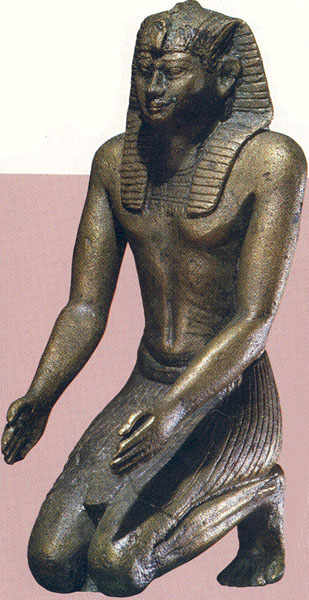

Virtually every major invader of Israel has had to fight a battle in the Jezreel Valley. Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites, Midianites, Amalekites, Philistines, Hasmoneans, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Muslims, Crusaders, Mamlukes, Mongols, Palestinians, French, Ottomans, British, Australians, Germans, Arabs and Israelis have all fought and died here. The names of the warring leaders who have battled in this small valley reverberate throughout history: Here, in 1479 B.C., Pharaoh Thutmose III fought the first battle in recorded history. Here, too, battled Deborah, Barak and Sisera (Judges 4:1–24, 5:1–31); Gideon conducted the first known night campaign here (Judges 6:3–8:28); and Saul and his son Jonathan fought their last heroic battle in the valley (1 Samuel 28–31; 2 Samuel 1; 1 Chronicles 10). Pharaoh Sheshonq I (c. 945–924 B.C.; probably the biblical pharaoh Shishak), fought here, as did the Israelite kings Jehu and Joram and Queen Jezebel (2 Kings 9:14–37; 2 Chronicles 22:5–9). Later, Antiochus, Ptolemy, Vespasian, Saladin, Napoleon and Allenbyd fought here. Indeed, the turbulent history of Israel and Judah, Canaan and Palestine, is reflected in microcosm in this blood-soaked little valley.

But what is it about this region that has prompted an almost continuous state of warfare?

The location: Although the Jezreel Valley is only 20 miles long by 7 miles wide, it runs across the breadth of Israel, connecting the Mediterranean Sea near Acco (Acre) in the west with the Jordan River and the lands beyond in the east. To its south rise the Carmel Mountains and the Gilboa Ridge. The valley lies at the juncture of several major north-south trade and military routes, including the Via Maris (the Way of the Sea), which linked Egypt with Mesopotamia in the east and Anatolia in the north. Thus whoever controlled the Jezreel Valley also controlled, by default, the trade and traffic through the area, be it of merchants or warriors, nomads or kings. And control of Megiddo equaled control of the Jezreel, for Megiddo is located in the center of the valley, overlooking the key pass through the Carmel Mountains, the Musmus Pass (also called the Wadi ‘Ara). As Pharaoh Thutmose III claimed in the 15th century B.C., “Capturing Megiddo is as good as capturing one thousand cities.” King Solomon, too, must have recognized the strategic importance of Megiddo, which according to the Bible, he fortified (1 Kings 9:15).

By John’s time, at least 13 battles had been fought at Megiddo and in the Jezreel Valley (four at Megiddo itself, four at Mount Tabor, one at Mount Gilboa, one at the Hill of Moreh [Endor], one at the city of Jezreel and two at other locations in the valley). While John could not possibly have known about all these battles, he undoubtedly knew those reported in the Bible—those of Deborah, Gideon, Saul and Josiah. He also probably knew of those fought nearer to his own era (the Hellenistic and Roman periods), such as the battles at Mount Tabor between Antiochus III and Ptolemy IV in 218 B.C.; between Gabinius, the Roman governor of Syria, and Alexander, the son of Aristobulus II in 55 B.C.; and between Vespasian and the Jewish rebels in 67 A.D—the last two of which were recorded by the first-century A.D. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus.10 To John, it must have seemed logical that a region that had seen so many battles, and so much bloodshed, would provide the setting for the opening salvos of the end-time battles.

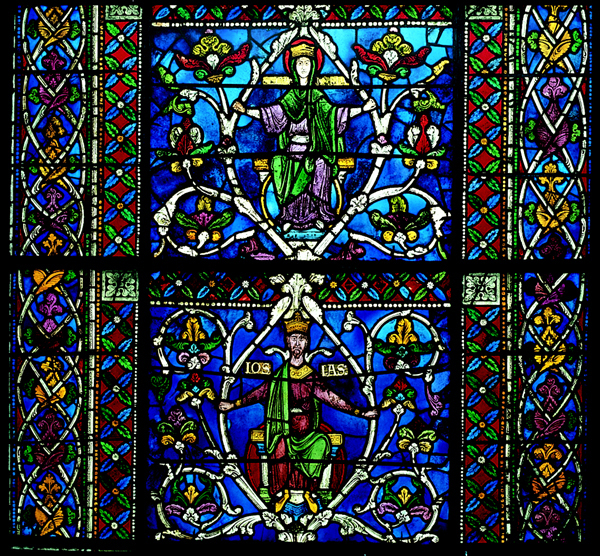

But even more important than John’s knowledge of the Jezreel Valley as an ancient battlefield was his awareness that King Josiah—Judah’s last effective, independent ruler from the House of David—had died in battle at Megiddo. For John, the coming of the Messiah at the battle of Armageddon would at last and forever restore the Davidic monarchy.

King Josiah ascended to the throne of Judah in 639 B.C. as a smooth-cheeked eight-year-old boy. Midway through his reign, he instituted a series of far-reaching reforms when a scroll of laws (probably a copy of Deuteronomy)e was “found” in the Temple in Jerusalem.11 Realizing that the people of Judah had strayed from Mosaic Law, Josiah implemented sweeping religious and political reforms, which included expanding Judah’s territory to the north and annexing Samaria and the Jezreel Valley. Hailed by later writers as a “second David,” not least because he was a legitimate descendant of the House of David, Josiah set out to return Judah to the greatness of the days of the United Monarchy of David and Solomon three centuries earlier. But when Josiah died at Megiddo, his dreams for a Judahite renaissance were buried with him.

On the surface, reconstructing the events that led to Josiah’s death in 609 B.C. would seem to be relatively straightforward, for there are accounts not only in 2 Kings 23:29–30 and 2 Chronicles 35:20–25, but also in the apocryphal First Book of Esdras 1:25–32 and in the writings of Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews 10.74). However, like eyewitnesses at a crime scene, each of these accounts offers its own version of what occurred.

If we reconstruct the events by combining all of the available sources, the story proceeds roughly as follows: In the late spring or early summer of 609 B.C., Pharaoh Necho II of Egypt and his army were hastening to the aid of their ally Assyria, preparing to fight against their common foe, the rising power of Babylonia. The battle was to be fought at Carchemish, in northern Syria, and Pharaoh Necho’s army had to traverse the length of Syria-Palestine to get there. Necho requested permission from Josiah, king of Judah, to march through his lands. But instead of granting the pharaoh’s request, Josiah marched his army into the Jezreel Valley and waited for the Egyptians to emerge from the narrow and dangerous Musmus Pass. Why he did this is not entirely clear (see sidebar to this article).

When the Egyptians finally crossed into the Jezreel Valley, they found the Judahite army waiting. King Josiah, dressed in disguise, was riding a chariot up and down his front line, encouraging his men. He sounded the attack and prepared to watch his forces annihilate the Egyptian invaders. Just as the battle got underway, however, an Egyptian archer let fly with an arrow that struck the Judahite king, mortally wounding him. Now either dead or dying (the accounts in 2 Kings 23:30 and 2 Chronicles 35:24 differ), Josiah was transferred to a second chariot and spirited south to Jerusalem, where he was buried, along with his dreams for a rejuvenated Judah.

The grieving Judahites named Jehoahaz, Josiah’s son, king, but Necho swiftly removed Jehoahaz to Egypt and set another son of Josiah, Jehoiakim, on the throne to rule as a puppet king.f

Although historians today have grave problems with this sort of hypothetical reconstruction, which pieces together the various accounts in Chronicles, Kings, Esdras and Josephus, John certainly would have been familiar with the story as reported in all its versions. John would have recognized Josiah as the last non-puppet ruler of Judah who belonged to the House of David. The wrong done to this good and just king needed to be avenged. And who better to do it than a Messiah descended from David? (John would have recognized Jesus as a descendant of David; in an effort to demonstrate Jesus’ claim as Messiah, the genealogy in the Gospel of Matthew [1:1–17] explicitly traces Jesus’ lineage back through Josiah to David.) So, when the Messiah leads his troops at Megiddo, he will not only exact revenge for the death of his ancestor, Josiah, but also restore the Davidic line to power in the very spot—Megiddo—where the line had been dealt a severe blow. Just as Josiah’s death at Megiddo had ended an era—that of the kingdom of God in the form of the House of David ruling first the United Monarchy and then the southern part of the Divided Monarchy from about 1000 to 587 B.C.—so the battle to be fought at Megiddo, Armageddon, would initiate a new era and reestablish the kingdom of God.12

John’s choice of Armageddon as the location for the battle may also have been influenced by the prophecies of Zechariah,g who refers to Megiddo in connection with the restoration of the Davidic monarchy. According to the prophet, on the day when the House of David is restored, the Lord will “destroy all the nations that come against Jerusalem.” On that day, “the mourning in Jerusalem will be as great as the mourning…in the plain of Megiddo” (Zechariah 12:9, 11).13

In military jargon, the battles at Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley have often been fought in what is known as a “contested periphery”—an area fought over by two forces, neither of which actually lives in the region. In the past 4,000 years, nearly a third of the battles fought at Megiddo were contested periphery battles. Of these, nearly four-fifths were won by the party who arrived second, that is, the last to the battlefield. This is good news indeed, since according to John, at the Battle of Armageddon the forces of heaven will attack only after the “kings of the whole world” have already gathered in the Jezreel Valley. Thus, I might risk a quite unscholarly yet most welcome prediction that the forces of good are the odds-on favorite to defeat the forces of evil, not only because John says that they will do so, but also because they will be the last to arrive at the battleground of Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley during the Battle of Armageddon.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Although Armageddon is mentioned only this once, Megiddo appears 12 times in the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, and once in the Apocrypha; it is not mentioned in the New Testament.

On the significance of thousand-year intervals in Jewish and Christian apocalyptic traditions, see James Tabor, “Why 2K?: The Jewish Roots of Millennialism,” BR 15:06.

See Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01.

Thutmose III captured Canaanite Megiddo by leading a sneak attack through the narrow, treacherous Musmus Pass. Almost 4,000 years later, during World War I, General Allenby modeled his march on Turkish-controlled Megiddo after the Egyptian pharaoh’s battle plans. See Eric H. Cline, “In Pharaoh’s Footsteps: History Repeats Itself in General Allenby’s 1918 March on Megiddo,” AO 01:02, and Cline’s letter to the editor in The Forum, AO 02:02.

See William Phipps, “A Woman Was the First to Declare Scripture Holy,” BR 06:02; and Moshe Weinfeld, “Deuteronomy’s Theological Revolution,” BR 12:01.

As Egypt and Babylon vied for control of Palestine, Jehoiakim switched loyalties, serving both empires in turn as vassal king. When he died in about 598/597 B.C.E., during one of Nebuchadnezzar’s campaigns in Palestine, Jehoiachin came to the throne. Within a year, Jehoiachin was exiled to Babylon, and Zedekiah, the last puppet king of Judah, was placed on the throne. Zedekiah, too, would rebel against Babylon—probably under Egypt’s influence. His reign ended in 586 B.C., when Babylon destroyed Jerusalem.

John routinely borrows imagery from the Old Testament prophets, including Zechariah. For example, both Zechariah (6:1–8) and John (Revelation 6:1–8) have visions of four horses of different colors, and John’s account of the last battle in Jerusalem (Revelation 20:9) seems to have been influenced by Zechariah 14.

Endnotes

This article is adapted from Eric Cline’s The Battles of Armageddon (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 2000) and is published here by permission of the University of Michigan Press (www.press.umich.edu).

George E. Ladd, A Commentary on the Revelation of John (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1972), p.7; J. Benton White, From Adam to Armageddon: A Survey of the Bible (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1986), p. 170; David A. deSilva, “The Social Setting of the Revelation of John: Conflicts Within, Fears Without,” Westminster Theological Journal 54 (1992), pp. 302–320; Bruce M. Metzger and Roland E. Murphy, eds., The New Oxford Annotated Bible, New Revised Standard Version (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1994), p. 363 NT; Robert H. Mounce, Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), pp. 8–21.

Hans K. LaRondelle, “The Biblical Concept of Armageddon,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (JETS) 28:1 (1985), p. 24; Ed Dobson, Fifty Remarkable Events Pointing to the End: Why Jesus Could Return by A.D. 2000 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1997), p. 136; cf. Edwin Yamauchi, “Updating the Armageddon Calendar: A Review of Walvoord’s Armageddon, Oil and the Middle East Crisis,” Christianity Today, 29 April 1991, p. 50.

The identity of these nations, which John labels Gog and Magog and which are also mentioned in Ezekiel 38–39, has been much debated. See esp. Ed Hindson, “Libya: A Part of Ezekiel’s Prophecy?” Fundamentalist Journal (June 1986), p. 57; and Meredith G. Kline, “Har Magedon: The End of the Millennium,” JETS 39:2 (1992), pp. 213–222.

Where exactly in or around Jerusalem this final battle will take place is debated, but the Valley of Jehoshaphat is thought to be the most likely location, based upon possibly related references in Ezekiel 38–39 and Joel 3:1–16. See Hindson, “Libya,” p. 58.

Ladd, Commentary, p. 216; William S. Lasor, The Truth About Armageddon (New York: Harper & Row, 1982), p. 144; Mounce, Book of Revelation, pp. 301–302.

Charles C. Torry, “Armageddon,” Harvard Theological Review 31 (1938), pp. 237–248; William H. Shea, “The Location and Significance of Armageddon in Rev. 16:16, ” Andrews University Seminar Series (AUSS) 18:2 (1980), pp. 159–160; LaRondelle, “The Biblical Concept of Armageddon,” p. 31; Roland E. Loasby, “‘Har-Magedon’ According to the Hebrew in the Setting of the Seven Last Plagues of Revelation 16, ” AUSS 27:2 (1989), pp. 130–132; Kline, “Har Magedon,” pp. 207–208, 212–213.

Yohanan Aharoni, “Megiddo,” in Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. Michael Avi-Yonah and Ephraim Stern (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Masada Press, 1977), vol. 3, p. 831; Aharon Kempinski, Megiddo: A City-State and Royal Centre in North Israel (Munich: Beck, 1989), pp. 15, 107; Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01; Mounce, Book of Revelation, p. 301 and n. 55.

Frank M. Cross and David N. Freedman, “Josiah’s Revolt Against Assyria,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 12 (1953), pp. 56–57; Nadav Na’aman, “The Kingdom of Judah Under Josiah,” Tel Aviv 18 (1991), pp. 3–71.

Stanley B. Frost, “The Death of Josiah: A Conspiracy of Silence,” Journal of Biblical Literature 87 (1968), p. 375; Graham I. Davies, Megiddo (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1986), pp. 104–105; Kempinski, Megiddo, p. 15.