I may have found a partial explanation for the basic law of kosher cooking, grounded in the Bible, of rigorously separating all forms of milk from all forms of meat.

I am an ethnoarchaeologist. I concentrate on what I think Biblical archaeology does best: reveal the everyday lives of ordinary people in ancient times. I am especially interested in the relationship between environment, food and diet, and the different work of men and women. For example, winter weather in the Levant, then as now, brought rain, which requires an increase in maintenance and home repairs and a greater reliance on preserved foods. Summer’s fresh succulent grapes became raisins for the winter. The same for dates and other fruits. Soured dairy products, legumes, vegetables and grains that had been preserved during the long, hot, dry summers provided healthy, tasty fare in the winter.

In a variety of ways, archaeological fieldwork addresses diet and cooking. Carbonized seeds, pollen, ancient plant drawings and animal bones help us reconstruct the ancient diet. Archaeologists have noticed that the condition of animal bones suggests that most meat was stewed or boiled, not roasted. This insight into meat-cooking practices is the first piece in the puzzle of kosher law.

A second type of fieldwork, ceramic ethno-archaeology, addresses many different questions about pottery, including how pottery for cooking and food preservation was made and used.

To help me understand this, I have observed working potters all over the world—in Jordan, in the Philippines and in Cyprus. My time in Cyprus was particularly illuminating. There, women potters still coil-build cooking pots, jugs and jars as their ancestors did, piling one wet coil of clay upon another and then smoothing the surface. Not only is the traditional technology preserved, but the vessel shapes themselves are remarkably reminiscent of ancient pottery.

In Cyprus traditional potters work only in the drier months. They stop when rain clouds threaten their unfired wares. They restart again in spring after Greek Orthodox Easter. One November, just before the close of the season, I observed a jar standing in an unusual place—in the open, exposed to the morning sun and cool night breezes. I assumed it contained yogurt, and I was right. Women would pour goat’s milk into used clay jars, koumnes (singular, koumna). No starter was added. The porous clay walls held the necessary old milk as a starter to sour the new milk. The women would use the yogurt to make trachanas, a traditional dairy bouillon cube that is a winter delicacy. The small rectangles of yogurt mixed with grain were drying on house rooftops all over the village.

A Cypriot woman who was Greek Orthodox—like everyone in the village—approached me while I was writing in my notebook.

“Of course,” she said, “you never put meat into a clay pot with milk.”

Startled, I asked her to explain. The sour milk, she told me, which clings inside the porous walls, sours the meat—that is, unless the pot has been refired for at least 12 hours in the potter’s kiln (kamini). I recalled my own mother once telling me that no amount of fresh milk can change the taste of souring milk; fresh milk, with even a drop of sour milk, tastes sour.

A similar reason accounts for the fact that old ceramic wine jars, pitharia, cost much more than new ones. The old, reused jars assured fermentation and a better-tasting wine.1 It was a lucky young woman who inherited an old sour-smelling yogurt pot and a used wine jar, instead of starting from scratch with new containers.

Could this reveal the origin of the Biblical rule that later became the basis of a whole dimension of Jewish kosher laws, namely, the prohibition against mixing milk and meat? Deuteronomy 14:21 stipulates that “You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” The reason for the Biblical prohibition, however, has been a puzzle for which explanations vary over the ages.

An early explanation was that animals have feelings, just as we have, and to kill a kid and then cook it in its own mother’s milk was cruel to all involved. Maimonides, the eminent medieval Jewish scholar of the 12th century C.E., suggested that boiling animals in their mothers’ milk was a Canaanite ritual associated with idolatry. “Meat boiled in milk is undoubtedly gross food, and makes overfull; but I think that most probably it is also prohibited because it is somehow connected with idolatry, forming perhaps part of the service or being used on some festival of the heathen. I find a support for this view in the circumstance that the Law mentions the prohibition twice after the commandment given concerning the festivals.”2 By prohibiting boiling meat in milk, the Israelites would avoid an element of Canaanite idol worship.

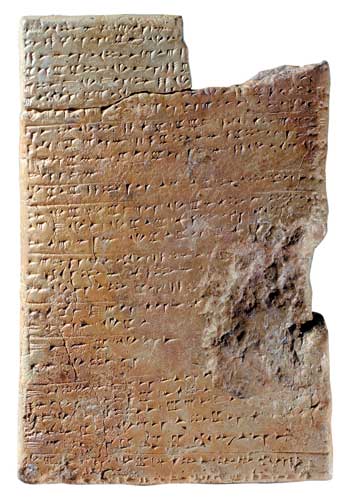

Remarkable confirmation of Maimonides’ explanation came in the form of a cuneiform tablet from Ugarit dating to around 1300 B.C.E. It describes a pagan Canaanite festival involving a kid boiled in its mother’s milk. It was thought that the tablet offered a clear context for the Israelites’ rejection of this practice. But this translation, which shows abundant Biblical influence, has since been discredited given the absence of a reference to mother’s milk. Nor is the goat mentioned in the cuneiform text.3

A few years ago in Bible Review, Jack Sasson offered a new translation for the Biblical text by changing the vowels for the crucial Hebrew word hlv.a Originally translated as halav, or “milk,” Sasson argues for a new pronunciation and reading as helev, or “fat.” “You may not cook a kid in its mother’s fat.” He sees the injunction as one originally designed to assure continued growth of the people’s herds (as this cooking method would require the slaughter of both kid and mother). With the development of later interpretations, however, this law became a key to the survival of the Jewish community throughout the ages. To maintain its identity through particular religious practices, such as not cooking meat with milk (or fat), the prohibition would help to separate, unify and preserve a people from those lacking rules governing meat consumption.

My ethnoarchaeological fieldwork in Cyprus may now offer a better explanation for not cooking a kid in milk. In times when people used porous clay pots to cook, everyone avoided cooking meat in containers used for milk products.

Not only did “others” refrain from mixing meat and milk in antiquity, they do so to this day. From about 300 B.C.E. in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible), the Hebrew word for “milk” was translated to the Greek word galaktos. To this day, traditional Cypriot potters make a goat-milking pot used by women, the galaftiri. It has an open mouth and side spout unlike jars used to process meat products. These pots are never used for meat. Nor are cooking pots ever used for dairy. The shape of the pot says it all—milk or meat. Rather than a dietary restriction limited to a single group of people, it was common practice to keep all ceramic pots used for milk versus meat separate.

From the prohibition of cooking meat in milk, the rabbis expanded the prohibition to include separation of all dairy and meat food items, and meat from dairy cooking utensils (including metal) and vice versa. The Talmudic injunction prohibits mixing milk and meat at meals, on the same plate or table, in the same sink or even in the stomach until sufficient time between meals passes.

Normally in antiquity, as in the Troodos Mountain villages of Cyprus to this day, meat is reserved for special occasions with family and friends. It would be terrible to ruin a fine meal with sour meat as a result of boiling it in a dairy pot. Simple logic kept dairy pots separate from pots used to cook meat. It’s possible that the Bible’s commandment to separate meat and milk boils down to good housekeeping. The straightforward, practical understanding of the Biblical passage originates in the prosaic perspective of a kitchen. It comes from those who make the pots, feed the animals, milk the goat, make the yogurt and cheese, cook the meat, and serve family, friends and community.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

Jack Sasson, “Should Cheeseburgers Be Kosher?” Bible Review 19:06.

Endnotes

1.

Giovanni Mariti, Wines of Cyprus (1772), translated by Gwyn Morris (Athens: Nicolas Books, 1984), p. 71.

2.

Maimonides, The Guide to the Perplexed, iii. 48.

3.

See Jeffrey H. Tigay, The JPS Torah Commentary—Deuteronomy (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996), p. 369, n. 29.