The magi lend an exotic and mysterious air to the Christmas story. The sweet domesticity of mother and child and the bucolic atmosphere of shepherds and stable are disturbed by the arrival of these strangers from the East. The background music changes from major to minor. Sentiment gives way to awe, perhaps even fear.

Nevertheless, or perhaps because of this, the legend of the magi has fired the imagination of Christians since the earliest times. In art, the adoration of the magi appeared earlier and far more frequently than any other scene of Jesus’ birth and infancy, including images of the babe in a manger. The artistic evidence suggests that the early church attributed great theological importance to the story of Jesus’ first visitors—an importance not overtly stated in this enigmatic gospel account of omens and dreams, astrological signs and precious gifts, fear and flight. To understand how the earliest Christians interpreted the message of the magi, we must look to early Christian literature (theological treatises, sermons and poetry)—and art.

“In the time of King Herod, after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, magi from the East came to Jerusalem asking: “Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? For we have observed his star at its rising and have come to pay him homage.”

So opens the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, the only biblical account of this nocturnal visit. In vivid contrast to Luke’s gospel,a Matthew omits any mention of Mary and Joseph’s trip to Bethlehem to be registered, a crowded inn, a sheltering manger, or watching shepherds startled by an angel’s announcement of the messiah’s birth. Instead, the first gospel focuses on the journey of these eastern emissaries, who see an unusual star rising, interpret it as an omen that they should investigate, and follow its path first to King Herod of Judea and then to Bethlehem, where it appears to stop above a house in which a child had recently been born. Entering the house, the men pay homage to the babe and offer him gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh. Then they leave, having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, who has hatched an evil plot that will lead to the slaughter of innocent children, the weeping of their mothers.

The earliest extant portrayal (see photo of fresco from the Catacomb of Priscilla) of the magi, dated to the mid-third century, appears above an arch in the Catacomb of Priscilla, in Rome.1 As in almost all the early images of the magi, they are shown as three men, identical in size, dress (although the color of their clothing varies in the catacomb painting) and race. Each carries a gift. It is difficult to discern the presents in the faded catacomb painting, but usually in art one of them carries a wreath and the others a bowl, jug or box-shaped object. The magi advance in a line toward the child seated on his mother’s lap. In many early images, they appear to point or gaze at a star overhead. Sometimes their camels appear behind them, as in a fourth-century sarcophagus relief in the Vatican Museums (see photo of fourth-century sarcophagus). The early images almost always appear in funerary settings—on catacomb walls and sarcophagi. The magi scene is among the first narrative images to appear in Christian art, and predates most other New Testament scenes as well as any other representation of Jesus’ nativity (a unique fresco [not shown] of Balaam and the Virgin with child in the Catacomb of Priscilla may be the exception). The complex composition and emphasis on narrative detail provide further evidence of the import the story held.

By the fifth century, Christian art had spread from catacombs and sarcophagi to vast public spaces, and the magi began to appear in the mosaic decorations of the first great basilicas. These mosaics share the same basic composition seen in earlier funerary art. In a sixth-century mosaic (above) from the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, in Ravenna, Italy, for example, the magi appear as extravagantly dressed triplets, bearing their gifts in fluted vessels as they press forward, gazing up at the star.b Before them, the baby Jesus is seated on Mary’s lap, flanked by angels.

The magi of the Ravenna mosaic may be distinguished only by their hair (one has long brown hair and a beard; one is a clean-shaven youth; the third is an elderly man, his hair greying) and their names (most likely a later addition), which are inscribed above them: Balthassar, Melchior and Gaspar (often spelled Caspar).

Neither their names, their number (three), their physical descriptions nor the date of the magi’s arrival appears in the Bible. Over time these cherished traditions were added to the brief gospel narrative, probably first through oral tradition. By the fourth century, the magi’s arrival was celebrated as the Feast of Epiphany on January 6 (12 days after Jesus’ birth on December 25).2 (Even today, in some parts of the Christian world, January 6, rather than December 25, is a time for exchanging presents, in commemoration of the gifts of the magi.)

Their assumed number was undoubtedly derived from the three gifts presented to Jesus in Matthew. The number wasn’t always taken for granted, however. A wall painting in the Roman catacomb of Domitilla shows four magi; one in the catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus depicts two. A variety of Syrian documents name twelve.3

The names and nationalities of the magi also varied throughout the world, especially in the East.4 An Armenian infancy gospelc from about 500 lists them as Melkon, King of Persia; Gaspar, King of India; and Baldassar, King of Arabia—and is thus closest to the Melchior, Caspar (or Gaspar) and Balthassar of the medieval Latin church.

As this Armenian infancy gospel indicates, the “magi,” a Greek term that might be taken as “sages” or “astrologers” (perhaps even “priests”), had come to be identified with royalty. In 490, the Byzantine emperor Zeno claimed to discover the remains of these “kings” somewhere in Persia and brought them to Constantinople. The relics eventually reached the West during the Crusades—first traveling to Milan and then subsequently to Cologne by Frederick Barbarossa in 1164. Today, they reside in Cologne, in a magnificent reliquary shrine built for them in the late 12th century. There they are known to pilgrims and tourists as the “Three Kings of Cologne.”5

It took centuries for these traditions to develop, however. In one of the earliest extrabiblical accounts of their journey, the apocryphal infancy gospel known as the Protevangelium of James, the magi remain unnamed and unnumbered.d This text, which was probably composed in Syria in about the mid-second century, only expands slightly on Matthew by describing the place where Jesus was born as a cave, rather than a house. (This detail will be familiar to modern pilgrims to Bethlehem who have been ushered into the small cave beneath the Church of the Nativity, where tradition locates Jesus’ birth.) The Protevangelium also elaborates on the appearance of the star: The magi tell Herod that all the other stars dimmed in comparison.6

The early church fathers interpreted the magi story in light of Old Testament prophecy. Christians understood the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures (the Septuagint) to be a sacred text that contained types and figures pointing to the coming of Jesus as Messiah.

Justin Martyr (died c. 165), in his dialogue with a Jew named Trypho, interprets the magi as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy regarding the coming of the messiah. Justin cites Isaiah 8:4, where the prophet predicts that “before the child knows how to call ‘My father’ or ‘My mother,’ the wealth of Damascus and the spoils of Samaria will be carried away by the king of Assyria.” For Justin, the magi were priests of an eastern cult and practitioners of magic and astrology. The wealth of Damascus and spoils of Samaria represented the sorcery and idol-worship that the pagan magi gave up when they worshiped Jesus. The magi’s visit to the crib was thus their moment of conversion and the renunciation of their misguided, idolatrous practices. And so Justin reads Matthew’s story as a sign to the world that Christianity was the true and pure faith.7

Writing from Carthage a generation after Justin, the apostolic father Tertullian expanded on Justin’s arguments, suggesting that the magi’s dream instructing them to go home by another route was not only to be understood literally, but as an admonition to forsake their former idolatrous habits and practices.8

This popular interpretation is reflected in art, which often links the three magi with the three Hebrew youths in the fiery furnace (Daniel 3) and with Daniel in the lions’ den (Daniel 6)—all easterners (Daniel and the Hebrew youths lived in the Persian court) who used their gifts of prophecy, dream interpretation and perhaps even magic to resist the evil of pagan idolatry. In art, the magi and these figures are connected in two ways: First, the magi, like the three youths, are usually garbed in the clothing that Romans associated with Persians and other easterners: short, belted tunics, cloaks pinned at one shoulder, soft pointed boots and peaked caps.9 Second, images of the magi are often paired with the three youths or Daniel, as in the fourth-century catacomb of Marcus and Marcellianus, in Rome (see photos, above), where paintings of the magi and the three youths are grouped together. In at least one image, the three youths from Daniel and the magi are conflated: On a fourth-century sarcophagus relief from St. Gilles, France, three men in eastern dress turn away from an idol and toward a star (see photo, below).10

The magi’s special role as witnesses to the true faith was also noted by the church father Origen, who read the magi’s stories in light of the prophecies of Balaam. According to Origen, after the star appeared to the magi, they noticed that their magic spells faltered and their power was sapped. Consulting their books, they discovered the prophecy of the oracle-reader Balaam, who saw a rising star “com[ing] out of Jacob” (Numbers 24:17) that indicated the advent of a great ruler of Israel. The magi thus conjectured that this ruler had entered the world. So, the magi traveled to Judea to find this ruler, and based on their reading of Balaam’s prophecy, the appearance of the comet and their loss of strength, they determined that he must be superior to any ordinary human—that his nature must be both human and divine.11 The magi, for Origen, are not simply Jesus’ first visitors, but the first to recognize Jesus as messiah.

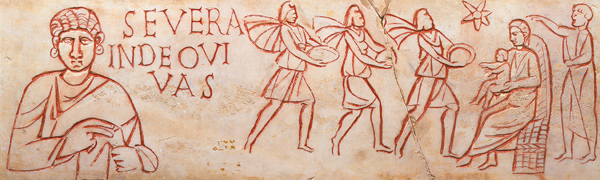

Whether or not Matthew intended to link Balaam’s star with the magi’s, the early church certainly did. Balaam’s figure may be barely discerned behind Mary and Jesus in the painting (see photo of fresco from the Catacomb of Priscilla) of the Adoration from the Catacomb of Priscilla. He also appears on the fourth-century funerary epitaph of a woman named Severa, where Balaam stands behind Mary, pointing at the star as the magi approach (see photo of inscription from fourth-century funerary plaque).12

By the third century, biblical interpreters were finding echoes of Psalm 72 in the narrative of the three gift-bearing visitors: “May the kings of Tarshish and of the isles render him tribute, may the kings of Sheba and Seba bring gifts! May all kings fall down before him, may all nations serve him” (Psalm 72:10–11). The magi were identified as these kings of “all nations” who worshiped the Christian messiah, bowing down to give him homage. They became a potent sign that Christ’s salvation was predicted and open to the whole world. The rising of the new star marked the coming of the new age envisioned in the Old Testament.

The passage from Psalms cemented the magi’s identification as kings and led to a fresh understanding of their origins.13 The earliest writers had understood the magi to come from one region (usually identified as Persia).14 But in the eighth century, the Anglo-Saxon historian and theologian known as the Venerable Bede recorded a later tradition that the three magi signified the three parts of the world—Africa, Asia and Europe—and that they thus might be linked with the sons of Noah, who fathered the three races of Earth (Genesis 10).

This development is also reflected in art. In the earliest sarcophagi reliefs and catacomb paintings, the magi appear to be three of a kind, all in “eastern” dress. Gradually, however, each acquires distinguishing characteristics. As we have seen, in the sixth-century mosaic from Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, the magi are represented as being different ages, with different color hair. By the 14th century, one of the three would appear as black (see photo of Andrea Mantegna’s “Adoration of the Magi”).15 As “kings” of all nations, the men also wear elaborate golden crowns in many later paintings (see the

What may be the most impressive and influential understanding of the magi weaves together many of the interpretations expressed by the church fathers: that the magi were the world’s first witnesses to the Trinity. This explains their appearance in almost all artistic images and literary traditions as three men, different, but alike.

The fourth and fifth centuries (when many of the images of the magi shown here were made) were a time of great theological debate—first over the relationships of the three persons of the Trinity, and subsequently about the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ. As the first visitors to recognize who this newborn child was, and what his birth would mean to the whole world, the witness of the magi was not insignificant to these controversies. Their three gifts seemed to demonstrate their prescient understanding of the three distinct persons who shared a single “nature” within the Trinity, as well as the different roles of the two separate but inseparable natures in the single person—the incarnate Jesus.

The second-century church father Irenaeus of Lyons alluded to this role of the magi in his allegorical interpretation of the magi’s gifts. According to Irenaeus, the magi offered Jesus myrrh (used for anointing corpses) to indicate that he was to die and be buried for the sake of mortal humans, gold because he was a king of an eternal kingdom, and frankincense (burnt on altars as divine offerings) because he was a god.17

Pope Leo the Great, whose writings on the divine and human nature of Jesus influenced the final formula for the orthodox Chalcedonian creed (451), wove together the ideas of Irenaeus (on Jesus’ nature) and Justin (on the renunciation of idolatry) when he emphasized that the conversion of the magi provides proof of Jesus’ two-fold nature (human and divine) as well as his status as king (both Davidic and heavenly). In addition, Leo hints that the journey of the magi to Jesus could be interpreted as an allegory of the journey of the individual soul to God, as the star’s light still might penetrate both the human mind and heart, showing it the way to truth. In his sermons on the Epiphany, Leo wrote:

How did it come to be that these men, who left their home country without having seen Jesus, and had not noticed anything in his appearance to enforce such systematic adoration, offered these particular gifts? It was the star that attracted their eyes, but the rays of truth also penetrated their hearts, so that before they started on their toilsome journey, they first understood that the One who was promised was owed gold as royalty, incense as divinity, and myrrh as mortal…and so it was of great advantage to us future people that this infant should be witnessed by these wise men.18

Centuries later, artists would depict what the magi were believed to have witnessed—the Trinity made manifest at the Nativity. The birth scene in the early-15th-century manuscript known as Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry, illuminated by the Limbourg brothers, includes God the Father in a cloud; the Spirit in the form of a descending dove; and the Son, the newborn babe lying on a bed of hay (see photo of early-15th-century Nativity scene).

Gifted with power to divine oracles and read stars, the magi recognized the child as the messiah, as both human and divine, king and child, intimately present and cosmically meaningful, mortal and eternal. For the early church, the magi themselves came to represent the Trinity. A final image of the magi, paired on a fourth-century marble sarcophagus with a scene of Jesus raising the dead (see photo, above), reinforces why their image appears so early and so frequently in funerary settings. In recognizing the promise of a messiah who was both human and divine—and eternal—the magi provided a message of hope for both the living and the dead.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

On the variations in the gospel accounts of the Nativity, see “Where Was Jesus Born?” BR 16:01, a debate between Steve Mason and Jerome Murphy-O’Connor.

For more on the mosaics of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, see Dennis Groh, “The Arian Controversy: How It Divided Early Christianity,” BR 10:01.

An infancy gospel is an apocryphal (noncanonical) gospel that recounts stories about Jesus’ and Mary’s parents as well as about Jesus’ birth and childhood.

See Ronald Hock (article) and David Cartlidge (captions), “The Favored One,” BR 17:03.

Endnotes

The painting appears in the catacomb’s Capella Graeca. A short, general discussion of the art is found in Neil MacGregor, Seeing Salvation: Images of Christ in Art (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 2000); and an older and finely detailed collection was done by Henri Leclercq, “Mages,” in the Dictionnaire d’archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie 10.1 (1920), pp. 980–1070.

On the development of the feast of Epiphany (which means “appearance” or “manifestation”), and the relative place of the Nativity, the baptism of Jesus, the miracle at Cana and the arrival of the magi as celebrated on this day, see Thomas Talley, The Origins of the Liturgical Year (New York: Pueblo, 1986), pp. 144–147, in which Talley shows that the development of January 6 as a celebration of the visit of the magi emerges when the date of the Feast of the Nativity is firmly established as December 25 (rather than January 6), and generally should be dated no earlier than the late fourth century. The Latin-speaking West shows this development earlier than the Greek or Syriac-speaking East, as shown by Augustine’s sermons and Prudentius’s hymn written for the feast of the Epiphany. See Augustine, Sermons 199, 200, 201, 202, 203 and 204; Prudentius, Hymn 12.

The determination of the 12 days between Jesus’ birth and the magi’s arrival in Bethlehem was most likely due to the reconciliation of the two different dates for Christmas in the first centuries (December 25 and January 6). Still, not everyone agreed, and different calculations remained. For instance, see Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 51.22.17, who not only argues that the magi took two years to arrive, but that they arrived on what he claimed to be the “very day of Epiphany”—the eighth day before the Ides of January, or 13 days after the increase of daylight (probably January 6 or 7, depending on which calendar he was using).

The unidentified author (Pseudo John Chrysostom) of the fifth- or sixth-century Opus Imperfectum in Matthaeum, Homily 2.2 (Patrologia Graeca 56:637–638) gives this number, probably on the basis of an apocryphal gospel attributed to Seth. This Syrian tradition had a parallel in parts of the Armenian Church. Also see the seventh- or eighth-century Chronicle of Zuqnin in which 12 magi are described as seeing different faces in the star, each a different age. Leo’s enumeration appears in Sermon 31.1, 36.1.

The eastern literature (Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, Armenian, Georgian and Persian) contained the greatest variety in names. The first documented appearance of the names in the West seems to be in the Excerpta latin barbari, ed. Theodore Mommsen, Monumenta Germaniae Historica: AA 9, Chronica minora 1 (Berlin, 1892), p. 278 (cited by R. McNally, “The Three Holy Kings in Early Irish Writing,” in Kyriakon: Festschrift Johannes Quasten, ed. Patrick Granfield and Josef Jungmann, [Münster/Westfalen, 1970], vol. 2, p. 670, n. 14). A detailed study of the names of the magi is by Bruce Metzger, “Names for the Nameless in the New Testament: A Study in the Growth of Christian Tradition,” Kyriakon, vol. 1, pp. 79–85. See also Hugo Kehrer, Die Heiligen Drei Könige in Literatur und Kunst, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1908–1909; reprint: Hildesheim, 1976), vol. 1., p. 68ff; and A. Bludau, “Namen der Namenlosen in den Evangelien,” Theologie und Glaube 21 (1928), p. 275ff.

Richard C. Trexler, The Journey of the Magi: Meanings in History of a Christian Story (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press), pp. 44–52. In 1903 the cardinal of Cologne sent some of the relics back to Milan.

Protevangelium James 21.1–3, in New Testament Apocrypha, vol. 1, ed. Edgar Hennecke and Wilhelm Schneemelcher (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1963), p. 386.

Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 77.4, 78.1. Although it might seem a stretch to the modern reader, Justin identifies Herod with the king of Assyria.

Tertullian, On Idolatry 9. This reading is repeated in the sixth century in a sermon of Caesarius of Arles, who (in his Sermon on the Epiphany, 194) describes the journey of the magi as a spiritual pilgrimage of conversion. See also Tertullian, Adversus Marcion 3.13.

Their outfits are also the standard costume worn by the popular mystery gods Orpheus and Mithras in late antiquity. Concerning their dress, see Thomas Mathews, The Clash of Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1993), p. 84. Here Mathews also makes this point about Orpheus. Mathews also cites Franz Cumont’s analysis of their dress as replicating that of captive barbarians. See Cumont, “L’adoration des Mages et l’art triumphal de Rome,” Memorie della Pontificia Accademia Roma di Archeologia 3 (1932–1933), pp. 81–105. On Orpheus’s role in Christian art, see Robin Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art (London and New York: Routledge, 2000); and M. Charles Murray, Rebirth and Afterlife: A Study of the Transmutation of Some Pagan Images in Early Christian Art (Oxford: BAR, 1981), pp. 37–63. On the comparison with Mithras, see Leroy A. Campbell, Mithraic Iconography and Ideology (Leiden: Brill, 1968).

Mathews (Clash, pp. 79–81) makes this point and argues against earlier analyses that the parallelism between the two sets of three orientally dressed characters was simply a case of mistaken identity. We also might recall that the three youths in the furnace were not alone. From a traditional Christian perspective, the fourth figure who appeared “like a God” (Daniel 3:25) was a precursor of Christ.

Origen, Contra Celsus 1.49–50. Also see Origen’s Homilies on Numbers 13.7, 15.4 on Balaam; as well as his commentary On Genesis 14.3 (in which he sees Abimelech, Ochozath and Philcol as prefiguring the magi).

On the story of Balaam as background to the Gospel Matthew, see Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977), pp. 190–196. Also see Jerome’s Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew 1.2.

Tertullian, for instance, in his treatise Adversus Marcion 3.13, reads Psalm 72 in this way, and understands the magi “as like kings” (fere reges). On their royal status, see also Caesarius of Arles.

Prudentius, for example, speaks of the magi as Persian. See Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 1.15; and John Chrysostom, Homilies on Matthew 6.2.

See a discussion of this in The Image of the Black in Western Art, ed. Jean Vercoutter, Jean Leclant, Frank M. Snowden and Jehan Desanges (New York: Morrow, 1976), vols. 2 and 3.

Some art historians have claimed that the magi are supposed to look like defeated and tribute-bearing barbarians, offering their homage to an earthly ruler. See Cumont, “L’adoration des Mages et l’art triumphal de Rome,” pp. 81–105; and André Grabar, Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1968), pp. 44–45. This interpretation is often applied to the mosaics from Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (c. 430) and Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, where Jesus and Mary are seated on a throne. However, as Mathews argues in Clash of Gods, one may argue that the image of Jesus enthroned suggests the transcendence of imperial power rather than the ratification of it.

Irenaeus, Adversus omnes Haerses 3.9. In the fifth century, Leo the Great repeats this interpretation in Sermon 33, 34, 36 where he speaks of the One Person with a “three-fold function”: God, mortal human, and king. Compare Fulgentius of Ruspe (a North African writer, c. 467–533), Letter to Ferrandus 20.