I have often lamented that, although there are thousands of museums in the United States devoted to every conceivable topic, there is not a single museum here devoted to Biblical archaeology.

I have recently been challenged on this assertion—and from a most unlikely source. I am wrong, I am told. There is a Biblical archaeology museum above a little shtibl in Boro Park, led by a chasidic rabbi.

For those unfamiliar with that rarefied world, let me unpack the previous sentence. Chasidim is a branch of Judaism that developed in eastern Europe in the 18th century. Chasidim often dress as their ancestors did in Poland, have long earlocks and pray with great fervor and excitement. A shtibl is a small prayer house, too small to be a called a synagogue. Boro Park is a section of Brooklyn where many Chasidim live.

Shaul (Hebrew for Saul) Deutsch is a chasid. The 37-year-old Deutsch was born and bred, however, in the United States. To hear him speak, you would not detect even a hint of the world in which he lives. He speaks “American” English, perhaps with a dash of Brooklynese. To see him, however, you would have no doubt—long black caftan, white shirt open at the neck, large beard and black hat. His beautiful ten-year-old son has curled earlocks about 9 inches long hanging from his ears.

When Rabbi Deutsch was eight years old, he was already studying Talmud, the arcane, brain-busting rabbinic text with which devout Jews spend a lifetime. The core of the Talmud is the Mishnah. Shaul and his teacher were studying the tractate on damages, Baba Kama. The particular passage concerned what would happen if a person left a kad in a public place: What if someone stumbled over it and broke it: Was the man who stumbled over it and broke it liable for damages? What if someone slipped on the water released by the kad and injured himself or was hurt by the broken pieces of the kad? Was the owner of the kad liable to the injured person for his injuries? In English translations, kad is variously translated pitcher, jug or pot. Shaul asked his teacher what a kad looked like. The teacher slapped him twice across the face. His teacher thought he was “acting up,” being a smart aleck, questioning the text. According to traditional study, everything is there in the text—no need to ask a question like this.

As Rabbi Deutsch now puts it, he was never one to take “no” for an answer. So he kept asking. Gradually, he looked at books. And he found answers—in archaeology. And he asked other questions. And he found more answers. And he became fascinated with archaeology. He was not becoming an apikoros (a heretic); he simply wanted to see the realia (although he would not use that word) that the holy texts were describing. When he was older, he visited museums around the world, from the Louvre in Paris to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Finally, he created the Living Torah Museum above the room that serves as the synagogue, or shul (the shtibl) that he leads. (He lives with his wife and five children in other rooms in the building.) One room of the museum is devoted to the Biblical period; the other, to the Second Temple and Rabbinic periods.

His is a teaching museum. When the holy text refers to a sword or a coin or a lamp or a seal, Rabbi Deutsch wants to show people what it looked like. He isn’t much concerned with exact dating—as long as the artifact illustrates what the text is referring to. The labels in the vitrines have no dates attached to them. But he does have one rule: No replicas. All the artifacts in the museum must be the real thing. The only exception is a tiny replica of the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum, which was the basis for deciphering hieroglyphics.

Rabbi Deutsch went about assembling the items in his museum in the only way he knew: Go to the most reputable antiquities dealers and follow their advice. He also has a number of museum-quality pieces on loan from well-known collectors. He estimates the market value of the pieces in his museum to be about a million dollars. The museum also has a small, but quite sophisticated research library: the holy books on one side, the archaeological tomes on the other.

He also has plans for the future. He dreams of a six-story building on a piece of land the community owns behind the present building. For this, he estimates, he needs between 15 and 20 million dollars. Will he get it? “Oh yes,” he says, “It’s just a matter of time.”

He says he has had no opposition from the observant, devout community in which he lives. Yeshiva students (a yeshiva is a traditional rabbinic academy) are flocking to the museum, he says. He recalls for them a passage or an episode from the holy texts and then points to the item that is being referred to in the text. That is what he wants to do, he says: to teach Torah (in its broadest sense, all religious learning) through archaeology. Even the heads of leading yeshivot have come to see and admire his museum, he says.

To make the experience as real as possible, Rabbi Deutsch displays, for example, handcuffs contributed by the New York Police Department side by side with ancient shackles.

An ancient beer jug has a built-in strainer to catch the dregs.

A complete set of ancient weights includes not only the shekel, but also the pym. A pym (sometimes spelled pim) was the price (or unit of weight) the Israelites had to pay the Philistines to sharpen an iron implement (1 Samuel 13:19–21).

Talmudic law requires an exceptionally sharp blade to be used in the kosher slaughter of animals. A sharp knife of obsidian (a type of glass) qualifies. But what if the sharp obsidian is still part of a formation in the ground, a Talmudic discussion asks. Can you slaughter the animal by drawing the animal’s neck across the stationary obsidian? One rabbi says no, but the rule is that the animal is validly slaughtered; it is kosher. Rabbi Deutsch displays a lump of obsidian to illustrate what the rabbinic text is talking about when it refers to something attached to the ground.

Another Talmudic discussion involves a situation in which vermin is found in one’s clothes on the Sabbath. Can one “press” (that is, kill) the vermin on the Sabbath, when “work” is forbidden? Some rabbis would do so and some would not. Raba, however, would throw the vermin into a likna of water instead of “pressing” them. What is a likna? Readers familiar with Greek pottery vessels will recognize in this rabbinic term a lekanis, a footed bowl with a cover, often beautifully decorated. With the cover on the lekanis, the vermin could not escape and would drown in the water. But the Sabbath prohibition would not be violated. Rabbi Deutsch can show his visitors what a likna/lekanis looks like.

Two things are not in Rabbi Deutsch’s museum—figurines or altars. Rabbi Deutsch does not want the museum to be offensive to strictly Orthodox Jews, he says. Figurines might be associated with idol worship. I asked him about human figures depicted on the coins on display. Only three-dimensional images are forbidden, he said.

Rabbi Deutsch emphasizes that he welcomes to his museum not only all Jews, regardless of how observant or unobservant, but non-Jews as well.

Rabbi Deutsch is, as you might expect, very knowledgeable archaeologically. He is well aware of the “forgery frenzy” now going on in Israel. I asked him if he was worried about forgeries. He said that he must rely on the most reputable antiquities dealers (some in the archaeological establishment would say this is an oxymoron). He told me that when three items were recently questioned, he took them off display.

He also displays some items with provenance; he knows where they came from. One of the prize pieces in his museum, he says, is the oldest complete copy of the Ten Commandments—well, actually, 11 commandments. They are the Samaritan version, which includes an extra commandment. And, well, the complete text has not survived. And we’re not sure of the date. The plaque on which the commandments are inscribed was allegedly found in 1913 near Yavneh in the course of excavations to build the Palestine-Egypt railway (see box, The Eleven Commandments).

There is a certain sweetness in the rabbi’s naivete, and, at the same time, a justifiable pride in his accomplishment. He has done what no one else in the United States (perhaps in the world outside of Israel) has done. With all the interest in the Bible, with all the interest in archaeology, no one else has done it. Maybe someone else would do it better, but all the big shots, all the people with access to the most sophisticated knowledge and current excavations, have not accomplished what Rabbi Deutsch has done.

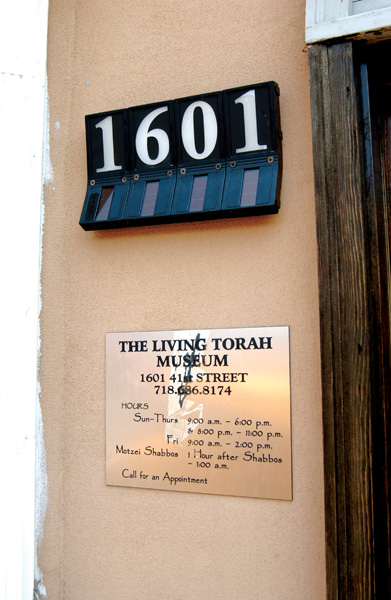

All photos courtesy of The Living Torah Museum. The museum is located at 1601 41st Street in Brooklyn. Hours: 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. and 8 p.m. to 11 p.m. daily. Closed Friday afternoon and Saturday until 1 hour after sundown and on Jewish holidays. Telephone: 718–686-8174. Website: www.torahmuseum.com.