Yigael Yadin distinguished himself in many roles—as a general, as an archaeologist, as a historian, as a scrollster and as a politician. On his performance of these roles, save that of scrollster, I have little information to add or ability to judge. For instance, I cannot assess his skills and faults as an archaeologist; I can merely note that he was continuously in the field, as the pontiffs of that profession then approved; and that he, more than most of his contemporaries, had a flair for choosing the most fruitful sites to dig, and for finding in them the most startling jackpots! Others, like the American James B. Pritchard and the Frenchman Claude Schaeffer, had that same heuristic gift. It is only rarely associated with technical competence in archaeology; at least, that is the complaint of those immaculate in technique, the skilled draftsmen of the balk and the cross-section, whose trench walls are as straight as if they had been made by a young nurse under the eye of the matron, but who, for all those merits, in fact never find anything exciting. Their complaint, however, is really directed not against their rival archaeologists, but against Unjust Fate. Surely, Yadin provoked an abundance of that sort of jealousy.

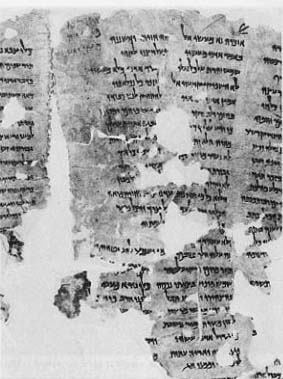

My first encounter with this multifaceted man was somewhat indirect. Ever since I reached the Arab Sector of Jerusalem in July 1954, I knew that Yadin, the son of Eleazar L. Sukenik, the Israeli archaeologist who had secured for Israel its first three Dead Sea Scrolls, had served the nascent Israeli army in high positions, as chief of operations in the War of Independence and then chief of staff from 1949 to 1952; he then, Cincinnatus-like, retired to follow his father’s profession in peace. That much was common gossip at the archaeological schools where I lived and at the suq. Our research group had the further information that he was preparing a commentary on one of the Scrolls his father had bought, the Rule for the War of the Children of Light with the Children of Darkness.

My interest was first caught by an article in Biblica, the journal of the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome, which reached me in my lodgings in the bed of the Kidron Brook in September 1955. There on the mine-scarred edge of no-man’s-land, I read an intriguing study on the strategy of King David’s wars with the Ammonites. The author, Yadin himself, explained the geographical-strategical problems the Israelite king faced when, from Jerusalem, he launched a campaign to capture Amman while warding off diversionary attacks from Amman’s Syrian allies. Of course, a reader in the “state over the wall” might sense a certain threat in this otherwise professional exposition, a threat to which the author was doubtless insensitive. Indeed, the article attracted attention in some of Jordan’s higher military circles, not usually to be found reading Biblica. At about the same time, I heard over Israel radio—“The Voice of Israel”—a precisely similar menacing tone in Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus: “See how the conquering hero comes.” How very different that had sounded in distant England.

For a long time after that remote encounter, Yadin and I had scarcely any contact—none in Jordanian Jerusalem, nor at various international congresses; by chance we never attended the same ones. At a distance, we read each other’s papers and exchanged offprints, but that was all.

At one time our work overlapped. While excavating at Masada, Yadin found a manuscript fragment of a sectarian work also found in Cave 4 at Qumran. I had published some of the Qumran fragments of the work a year before. To this day it remains a paradox why a work composed by the sect at Qumran was found at Masada—it is as if one were to find a Roman (Catholic) missal in the archives of a Communist cell. Yadin and I were each well aware of what the other was doing on this newly discovered work, but, strangely, neither wrote to the other with any possible explanation of this oddity, or thought of collaborating in publishing the remaining fragments of the work we each had. Thus it was, even though by then I was in America and he was often there too; and mail connections between there and Israel were not unthinkable, even if unreliable. It must have been that, both being properly educated, we had not yet been properly introduced!

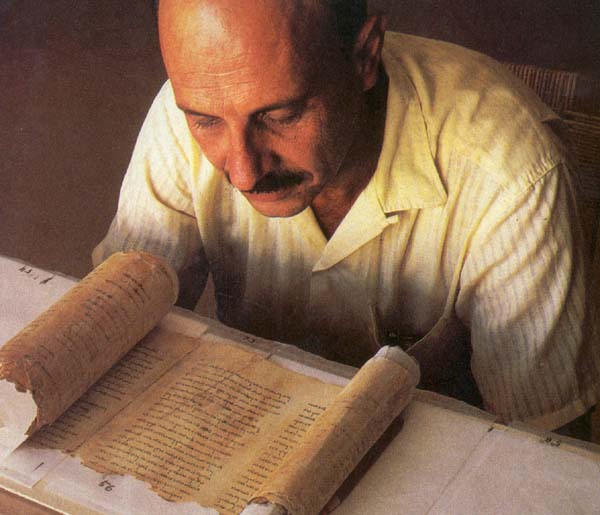

When I went in 1966 to Harvard, a place with fairly close contacts with the Hebrew University, and where indeed Yadin a couple of years beforehand had been a visiting professor, a closer intellectual relationship began. Yadin had published an edition with commentary on another fragmentary manuscript from Masada, containing some five columns of the apocryphal collection of proverbs of the Jewish sage Jesus Ben Sira. Yadin’s edition was a remarkable achievement of textual and philological criticism in a much-trodden field, especially because his training was in areas very different from text-critical skills; it was remarkable, but, as one might have expected (and as I tried gently to imply to him in a substantial review), his edition was frequently erroneous, or at least could be considerably improved.

Properly fortified with an introduction from my Harvard colleague Frank Cross, I sent the manuscript of my review to Yadin, asking him to check the Masada manuscript itself for me on certain tricky points where I was unsure of my revised readings (made on the basis of the published photographs), and suggesting further possibilities he might consider. Almost immediately Yadin answered, accepting the bulk of my changes, discussing the difficulties that the manuscript’s readings created for me or him in certain passages and suggesting that my article be published in the forthcoming volume of Eretz Israel, a prestigious series of roughly biennial commemorative volumes. Indeed, Yadin’s own edition of the Ben Sira manuscript had appeared in the most recent volume; he had the entrée, and could guarantee that my paper would be accepted. I was glad to avail myself of his sponsorship.

In writing my review, I aimed, or so I thought, only to make detailed observations and emendations, and to help create a more reliable edition that was likely to last as the basis for all future studies. No one who understands the preparation of such editions will imagine that I intended to show that members of our Dead Sea Scroll editorial team had higher standards of accuracy and criticism than Yadin’s. But perhaps I hoped that a “Renaissance man” like himself would accept more collective collegial approaches, at least when the texts require other competencies in which he would be but a beginner. Providentially my article convinced Yadin that, at least in those five chapters of Ben Sira, he should treat me on an equal footing, or at least as a beginner whose scholarship, however, was to be taken seriously.

In 1967, after the Six-Day War, when our team’s scrolls became war booty, or redeemed national treasure—à chacun sa terminologie—Yadin, long since an eminence grise in Israel, joining politics and archaeology, now became the principal authority on the Israeli side for deciding how to deal with our own international team of editors and with the scrolls we had been editing—both being the spoils of victory. A group of Israeli scholars of various competencies hastily drew up a catalogue of the plates of Dead Sea Scroll fragments that their army had “liberated” in the Palestine Archaeological Museum. That cataloguing still has baneful effects today, because the new catalogers didn’t ask our team for the detailed and rational catalogues we had already made; instead, they rearranged everything in the haphazard order in which they took each plate out from its storage place. Their need to make a new catalogue, and a hasty one at that, looked more like an excuse for holding a long reading party in the museum, where the “chosen” group, in secret from us, could rapidly read through everything and survey the content of their new acquisitions, discovering, reidentifying or even ludicrously misidentifying the larger fragments. I could give amusing examples! Of course all this had been better done by us some ten years earlier. Our lists would have been shared with them if any requests had properly been made. In later years, I heard echoes of this orgy of reading in my discussions with Yadin, as he from time to time brought out reliable or unreliable snippets of information from the storehouses of his own reading.

More important is the role Yadin played in the discussions the Israeli government held on the terms under which the international editorial team could continue its publication project. In these discussions, Yadin the scholar could be relied on to recognize what rights scholarly propriety protected. At the same time, Yadin was so well viewed as a patriot and statesman that any reconciliation between the demands of scholarship and those of national interest and honor that he accepted would also be acceptable to the political authorities and the public.

In these discussions on lofty questions of principle, I was not involved. For the team’s side, they were conducted mainly by Père Roland de Vaux. Since I was in Jerusalem, de Vaux kept me au courant. The special task he assigned me, as the first of the editors to return to Jerusalem for a sustained period after the 1967 war, was to knock on the doors of various authorities and press them to give me (and, in the future, my colleagues) the same conditions of work and support that we had enjoyed in the Hashemite past—or something as near to the same conditions as possible. This I intentionally did with apparent insensitivity to the existence of any political problems, obstinately concentrating on restoring as near as possible the status quo ante. I relied not on any arguments about rights but on their respect for me as a scholar. I asked (as if unaware that they might have difficulties), for all that I had needed and had in the past, and would still need for the future. I was well aware that success or failure depended on my discussions with Yadin. However, in our close communication, each of us tried to feel out the other, to spar with the other, to understand him. We did not need to assure ourselves of the other’s scholarship—we had each read enough of the other’s work for that not to be an issue—but Yadin, at least, needed to judge my reliability and mettle and to assess the likelihood that I would be able to accomplish what I was undertaking on the team’s behalf.

I had recently bloodied him about his edition of Ben Sira, and that certainly helped at the start in establishing the authority of my criticism. But I remember thinking at the end of our rambling conversations that it was those attitudes we shared that were in fact producing the outcome I desired. For Yadin and I both had English educations—mine the well-trodden path of the grammar school and public school, his the education of generations of Jewish and Arab youth in Mandate Palestine, which marked them with a recognizably English stamp. We were trained in various ways, but always as gentlemen. Not that we were ever quite at ease with each other. Even at our most intimate we used surnames; always he called me “Strugnell,” and I called him “Professor Yadin,” for he was some 15 years older than I. I never thought of him as a friend, but certainly respected him extraordinarily as a fellow worker and scholar.

In our conversations there was always a certain reticence—on his part, was it deviousness? At times Yadin didn’t mention to me material relevant to our discussions, material which, I later found out, he knew perfectly well. Thus, in our first discussion of the Temple Scroll (which he acquired after the Six-Day War and which he was to edit—more of this later), he did not tell me that, during the Israeli party’s leisurely ramblings through the Palestine Archaeological Museum’s holdings of Cave 4 and Cave 11 fragments that our team was editing, he had been able to identify fragments of several other manuscripts of the Temple Scroll. He had also found some “Temple Scroll fragments” with an apparently Biblical manuscript that I had been editing for years. He simply separated out from the Biblical text those fragments that corresponded to the text of his Temple Scroll. Although I was not to know it until his edition of the Temple Scroll appeared some ten years later, Yadin decided to take over these fragments and publish them as another Cave 4 manuscript of the Temple Scroll. That he decided to publish fragments properly assigned to and studied by another scholar is perhaps a minor matter of etiquette; such agreed-upon changes in assignments were frequently made among us by mutual consent, as study and discovery advanced. However, he did considerable damage to his own edition: By not consulting with the scholars who had been working for several years on the fragments he had appropriated, he deprived himself of knowledge that would have greatly modified and improved his understanding of those fragments.

I used to dismiss these things with wry amusement, as quirks of Yadin’s character. Were they examples of a tendency to keep all Qumran matters and related information to himself? If so, he was a greater “monopolist” and hoarder than anyone on our team. Those who tar us with that charge, however, usually heroize Yadin as a chevalier sans peur et sans reproche. Or was his the prudence of a good general, keeping strict controls on the need to know, with his cards close to his chest, his maps and codes kept under lock and key? As I look back over the conversations I had with Yadin, I recognize that his reticence was at times a most effective tactic. But in many cases it was just habitual and unthinking, with no further aim—another mark of what I have loosely described as his English-like character. In any case—although this is sheer guesswork on my part—I must have passed his character test, for after that I received from the Israel Antiquities Department not merely verbal assent to my requests, but real action in response to them.

Other manuscript fragments of the Temple Scroll—from Cave 11—that Yadin “found” in the Museum at the same time and that he dealt with in the same cavalier, absorbing and somewhat devious fashion are even more embarrassing for Yadin’s reputation. Again Yadin displayed haste and insensitivity toward the rights of foreign scholars. Whereas one could argue that the Cave 4 fragments we have mentioned had once been the property of the Jordanian government, but then became spoils of war of the Israeli government and were later annexed at the time of the annexation of Jerusalem, the Cave 11 fragments were very different. These fragments had been bought for the Jordanians by the Dutch government and the Amsterdam Academy of Science, in return for the understanding that the Jordanians would specifically assign the rights of study, first edition, to the Academy’s scholars. The neglect of the conditions binding the owner of the fragments—that is, the Jordanians, when the manuscripts were in their possession, and thus theoretically the Israelis when they succeeded to possession of them—led to a highly embarrassing moment at the 1976 Journees Bibliques de Louvain, when Yadin, in happy ignorance of the legal niceties, announced his forthcoming edition of those fragments in the presence of those same Dutch scholars who, unaware of Yadin’s peculation, had themselves for a long time been preparing the same fragments for publication.

As I look back at the results of the other discussions, not those I had with Yadin, but those between de Vaux and later Pierre Benoit (on behalf of our team) and the Israelis—among whom, of course, Yadin was clearly the most influential—I ask myself how we should assess Yadin’s contribution to those negotiations, which formed the basis for the international team’s continuing at work. Yadin himself in his published writings is not too enthusiastic: He followed what he perceived as the standard practice among scholars, although he would have preferred to follow the dictates of national feeling and take things over at least in part. But he found an odd moral satisfaction in abstaining from the attractions of so noble a sin! At the end, he regretted that the promises that our group gave of greater haste had not been kept—what naiveté. My own judgment on his contribution has, of course, the advantage of hindsight; I now wish—though of course I would have resisted it furiously then!—that he had pressed me harder to bind ourselves to enforceable, exacter, and nearer targets and goals. This would have lead our group to realize more quickly that, although according to law and current scholarly custom our lots had been quite properly constituted and we had properly acquired editorial responsibility for them, it was time for us to recognize the bare facts and to enlarge the circle of our collaborators, to unstop those bottlenecks of which we, even more than others, were much aware. In fact, within the decade, many of our team’s members, each on his own initiative, would take steps in that very direction, and speed would become not just a chimeric hope. En passant, more Israelis and Jews would be joining that group of editors of Cave 4 manuscripts, far larger in number than would ever have had access to the manu-scripts that had been hidden away in Yadin’s desk at his death for almost as long as the PAM (Palestine Archaeological Museum) fragments ever were!

But unfortunately Yadin was too like us. In acquiring “our” manuscripts, we all had had the healthy appetite of youth—in youth natural, but in middle age that same appetite, whether it be for food or scrolls, others rightfully charge as gluttony, to be checked by abstemiousness and dieting. Yadin, unable to diagnose his own disease, was also unable to treat it correctly in others. He should have cultivated, and encouraged by persuasion, the growth of more realistic attitudes in both projects—“both,” I say, for his needed them no less than ours. He could have favored an evolution from a “centralized monarchy” through the various stages of feudalism to the present stage—I forbear from finding an appropriate characterization of the present stage—“late feudalism,” “the rise of the middle classes”? Yadin, for all his scholarly brilliance and political power, missed his chance to confront the real problems preventing greater speed in publication, a direction in which we in de Vaux’s group were beginning to move. As his later conduct with most of his manuscripts also showed, Yadin was certainly the wrong man for that job!

I have used the characterizations of “greed,” “appetite,” “monopoly,” when talking of Yadin’s formation of his own Grand Duchy. I don’t know what conscious intentions in fact inspired him in joining domain to domain, but “appetite” will serve as an adequate objective description. Only twice, as far as I know, did he envisage taking on a helper for himself to get one document or another edited. Once it was his own very senior colleague, Professor H. J. Polotsky of the Hebrew University, with whom he associated himself for the Greek texts from the Nahal Hever. The other was my own junior colleague, Carol Newsom, now of Emory University, who saw that collaboration would be the only way of getting the Masada Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice out of his desk and published—she needed it to include in her edition of the other eight manuscripts of these texts from Qumran. She won his agreement to a joint edition by proposing that she could produce a first draft, which he would then revise. This proposal unblocked the logjam.

By the time of Yadin’s death in 1984, his desk was filled with unpublished literary texts from his excavations at Masada and elsewhere in the Judean desert, as well as further material from his excavations at Hazor—no sign could be seen that any work had been done on them or farmed out to others. Fortunately, Yadin’s executors moved aggressively to name a group of suitably qualified Jewish senior collaborators and to set up a rough timetable to stimulate publication of these hoards, which had lain untouched in their caves, his drawers, for 20 years or so.

When he died, almost none of the documents from his days at Masada and Nahal Hever had been much studied even after 25 years, and only a very few of them had been published. These had been rigorously kept away from the younger Israeli scholars, yet it was our group that was reproached for keeping other scholars away from our documents. Somewhat unfair! For several years we at least had been bringing in younger scholars and assigning documents to them.

Notice the effect of what might be called Yadin’s tendency to run a monopoly: In Qumranology no disciples were trained by him, nor senior nor junior, to help him with this mass of material.

A little more and I will have done. In the early spring of 1982–1983, I was in my office at Harvard one day and the phone rang; it was Yadin speaking from Jerusalem. A congress was to take place in Jerusalem in April of 1983 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the first meeting of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society in 1908, a group that had since grown into the present Israel Exploration Society. I had earlier declined this invitation because of the press of business at Harvard, but Yadin suggested that Elisha Qimron, my colleague in preparing the edition of the important text 4QMMT, could read on our joint behalf a paper announcing some of the principal discoveries that were coming out of our studies. Qimron, Yadin said, had already written a draft, and all I would have to do would be to modify it, as much as I had time for! Qimron really needed such a publication to help in his promotion in his university, Beer-Sheva. Argument for argument, you could see the telephone wire being twisted from Jerusalem to Cambridge! The considerations about Qimron’s future were of course unanswerable. My only serious hesitations were that such a publication would create pressures on us for a too precipitate publication of the whole document, before we could complete our systematic plans for what we still considered just a preliminary edition, though admittedly a longish one. Some works present greater difficulties than others and this was one of the most difficult. I didn’t want our rationally planned and well-balanced preliminary edition to be turned into a hasty stopgap, to be thrown to the wolves of the yellow press. It could well be that I used just such expressive phrases to Yadin, sure that in his heart of hearts he would share the sentiments, if not the mixed metaphors. “Don’t worry,” said he, “I can stop that sort of thing. I’ll look after you.”

This was comforting. The Congress, with Qimron reading our paper, was a great success. The wolf pack stirred, but its salivating was restrained—Yadin’s influence was widespread. But suddenly, he died—our protektsiya was gone and the pack was off again racing after MMT on all fours.

His death was felt at the national level, and he received commemorative speeches full and fulsome. However well these eulogies of the archaeologist and general were deserved I cannot judge; as for the scrollster, he was certainly the most imposing figure among the Israeli scholars, and one with by far the greatest achievements. But as eulogy follows eulogy and as he evolves into a role model for a younger generation and a guide for their professional conduct, as the hero cult turns into a cult of personality, I feel I should do a kindness to my Israeli colleagues by saying, “True, but … ,” by insisting that he was human and had his faults too, so that the model, if that is what he will provide, will be followed more critically and with greater equilibrium by the next generation. Generally, Yadin deserved the eulogies he received but, as one of the scrolls, the Manual of Discipline, says, “Perfection does not belong to mankind.” His panegyrists tend to suggest the contrary. I have decided that a few warts should be left on the portrait, for balance.

Yadin was a generalist, a hoarder and a monopolist. Although my encounters with him always came out well, whoever won, I had always to remember that his interests ran different from ours, and had done so ever since the days when he was smuggling our scrolls! Above all, I regretted that he trained no students in Qumran studies, and that the circumstances of his compulsory purchase of the Temple Scroll damaged the long established relationship with the Bedouin.