Jewish Monotheism and Christian Theology

“In the beginning was the Word” reads the opening verse of the Gospel of John, “and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” In the context of the gospel, it is clear that the Word is identified with Jesus of Nazareth, the charismatic preacher who had been crucified by the Romans some 60 years before the gospel was written. John’s gospel is exceptional in the New Testament for the explicitness of its claim that Jesus was divine. Nonetheless, it is both the culmination of a trend within Judaism and a good indicator of the course Christian theology would take in the following centuries. This development would accentuate the gap between emerging Christianity and Judaism.

By nearly all accounts, at the end of the first century C.E. strict monotheism had long been one of the pillars of Judaism.1

John takes pains to show how unacceptable Jesus’ claim of divinity was to Jews: “For this reason the Jews were seeking all the more to kill him, because he was not only breaking the Sabbath, but was also calling God his own Father, thereby making himself equal to God” (John 5:18). This gospel is traditionally attributed to one of the Jewish disciples of Jesus. Even though that attribution is problematic, the Christian movement had unquestionably originated in the heart of Judaism little more than half a century earlier. Yet, in the opinion of one modern scholar, John’s version of a divine Jesus is so elevated that observant Jews at the beginning of the first century C.E.—including the first apostles—could not have believed in such a figure.2 The question is, How was it possible for first-century C.E. Jews to accept this man Jesus as the pre-existent Son of God and still believe, as they surely did, that they were not violating traditional Jewish monotheism? How did this development come about?

Was Judaism Monotheistic?

Jewish monotheism, which gave birth to the Christian movement, was not as clear cut and simple as is generally believed. Several kinds of quasi-divine figures appear in Jewish texts from the Hellenistic period that seem to call for some qualification of the idea of monotheism. We will consider three categories of such figures—angels or demigods, exalted human beings and the more abstract figures of Wisdom and the Word (Logos).3

Angelic Figures

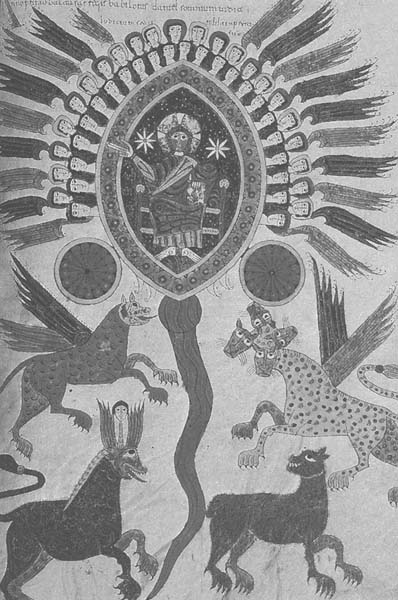

The latest book of the Hebrew Bible contains a passage that had great significance for early Christians. In the Book of Daniel, the visionary sees that “thrones were set in place and an Ancient One took his throne, his clothing was white as snow, and the hair of his head like pure wool; his throne was fiery flames, and its wheels were burning fire” (Daniel 7:9). The Ancient One is the God of Israel, even though some of his features, like his white hair, are reminiscent of the ancient Canaanite god El. The ancient rabbis were troubled by the plural term “thrones,” which indicates that at least one other figure will be enthroned. Indeed, a second figure makes his entrance a few verses later:

I saw one like a son of man

coming with the clouds of heaven.

And he came to the Ancient One

and was presented before him.

To him was given dominion

and glory and kingship,

that all peoples, nations and languages

should serve him.

His dominion is an everlasting dominion

that shall not pass away,

and his kingship is one

that shall never be destroyed.Daniel 7:13–14

Monotheistic theologians commonly interpret the “one like a son of man” as a symbol for Israel.4 The figure does indeed represent Israel in some sense, but the manner in which he is presented cannot be brushed aside so lightly.5 Elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, a figure riding on the clouds is always the Lord, the God of Israel.a Daniel’s imagery has its background in ancient Canaanite mythology, in which the god Ba‘al rides the clouds and is distinct from the venerable, white-bearded El. In Daniel’s vision, the second heavenly figure, the rider on the clouds, is most plausibly identified as the archangel Michael, who is introduced as “the prince of Israel” later in the book (Daniel 10:13). Canaanite mythology is thus transformed; it is not entirely dead.6 In later Jewish tradition, this text from Daniel proved controversial because it provided a basis for the idea that there are “two powers in heaven.”7 The rabbis rejected this idea as heretical, but nonetheless it was evidently held by some Jews—as well as by Christians.

The “one like a son of man” in Daniel is what we might call a super-angel. This kind of figure appears quite regularly in Jewish texts around the turn of the era.8 Consider the following passage from Psalm 82 in the fragmentary Melchizedek scroll from Qumran Cave 11: “Elohim [God] has taken his place in the divine council; in the midst of the gods he holds judgment.” The scroll then provides a gloss on the quoted passage: “Its interpretation concerns Belial and the spirits of his lot [who] rebelled by turning away from the precepts of God … and Melchizedek will avenge the vengeance of the judgments of God.”9 The Elohim who rises for judgment in the divine council is here identified as Melchizedek (the identification is probably even more explicit in a later, fragmentary, passage). Another text, the Testament of Amram, tells us that Melchizedek was one of the names for an angel who was also known as Michael and the Prince of Light; this good angel was paired with the evil angel Melchiresha, also known as Belial or the Prince of Darkness.10 Both Michael and the Prince of Light appear in other Qumran scrolls, most notably the War Scroll. What is striking about Melchizedek in the Cave 11 text is that he is identified as an elohim, a god. But, in fact, this usage is not exceptional. The great Jewish scholar Yigael Yadin pointed out 40 years ago that the beings we call angels are called elim, gods, in the War Scroll,11 and the same usage can be found in the Songs of Sabbath Sacrifice, an early mystical text also found at Qumran.12

Given the appearance of such semidivine figures in Jewish texts, the term “monotheism” is not entirely felicitous as a description of Jewish beliefs in this pre-Christian period. Yet it is not entirely inappropriate either. These texts always distinguish clearly between the supreme God and his angelic lieutenant. In the Qumran War Scroll, for example, a passage about the Prince of Light is quickly followed by a question addressed to God: “Which angel or prince can compare with thy succor?” (column 12). It is also true that these principal angels are not usually worshiped, but the issue of worship is not as straightforward as is sometimes supposed. The “one like a son of man” in Daniel is given dominion and glory and kingship, and all peoples serve him. Whether this constitutes worship would seem to be a matter of definition.

The “one like a son of man” underwent some development in Jewish tradition, quite apart from the adaptation of this imagery in Christianity.13 In the Similitudes of Enoch,b a work of uncertain, but clearly Jewish, origin and probably dating to the first century C.E., the visionary sees “one who had a head of days, and his head was white like wool, and with him there was another whose face had the appearance of a man and his face was full of grace, like one of the holy angels” (1 Enoch 46:1). The latter figure is subsequently referred to as “that Son of Man.” It is said of this figure that “his name was named” before the sun and the stars. He is hidden with God, only to be revealed at the Judgment. Later, in the Judgment scene, this figure is, like God, set on a throne of glory, and the kings of the earth are commanded to acknowledge him (1 Enoch 60–62). Finally, at the end of the Similitudes, Enoch is lifted aloft into the presence of that Son of Man; he is then greeted by an angel, who tells him, “you are the Son of Man who is born to righteousness” (1 Enoch 71:14). Whether this means that Enoch himself is identified with the same Son of Man he had seen in his visions is disputed. The passage can also be translated as “you are a son of man [that is, a human being] who has righteousness.” It is also possible that this passage is a later addition to the text, intended to counter the Christian claim that Jesus was the Son of Man by identifying this figure with the Jewish prophet Enoch. In any case, this non-Christian Jewish text provides an intriguing example of the exaltation of a human being to the heavenly realm.

This tradition of the super-angel reached a climax several centuries later, in another Jewish text known as 3 Enoch or Seper Hekalot.14 A figure known as Metatron, Prince of the Divine Presence, is “called by the name of the Creator with seventy names … [and is] greater than all the princes, more exalted than all the angels, more beloved than all the ministers, more honored than all the hosts and elevated over all potentates in sovereignty, greatness and glory” (3 Enoch 4:1). Metatron is given a throne like the throne of glory (3 Enoch 10:1) and is even called “the lesser YHWH” (3 Enoch 12:5). When Ah

eµr, one of the four sages reputed to have ascended to Paradise in the early second century C.E., sees Metatron seated as a king with ministering angels beside him as servants, Aheµr declares, “There are indeed two powers in heaven!” (3 Enoch 16:3). Because of this, we are told, Metatron is dethroned and given 60 lashes of fire.

Metatron’s punishment suggests that there was some controversy about his exalted status at the time 3 Enoch was written. But the tradition that he had a throne in heaven could not be suppressed entirely. Metatron is still identified with Enoch, son of Jared, who was taken up to heaven before the Flood (see Genesis 5:24). Evidently, Metatron is a later development of the Son of Man figure in the Similitudes of Enoch, and has attained an even more exalted rank in the intervening centuries.

Exalted Human Beings

The case of Enoch brings us to a second kind of divine being under the Most High God: the exalted human being. In Daniel 12, the righteous martyrs of the Maccabean era are promised that they will shine like the brightness of the firmament and be like the stars forever and ever. In 1 Enoch 104, this imagery is clarified: “You will shine like the lights of heaven … and the gate of heaven will be opened to you … for you will have great joy like the angels of heaven … for you will be companions to the host of heaven.”

In the idiom of apocalyptic literature, the stars are the angelic host. When the righteous dead become like the stars, they become like the angels; in the Hellenistic world, to become a star was to become a god. We find a reflection of this way of thinking in a Jewish wisdom text attributed to the Greek gnomic poet Phocylides. The author expresses the hope “that the remains of the departed will soon come to the light again out of the earth, and afterwards become gods.”15 This does not mean, of course, that the righteous dead are on a par with the Most High God (or with the Olympian gods) or that worship should be directed toward them (although the dead have been worshiped in many cultures). But it does indicate that the line separating the divine from the human in ancient Judaism was not as absolute as is sometimes supposed.

Some exalted human beings were more important than others. In the second century B.C.E., an Alexandrian Jew named Ezekiel wrote a Greek tragedy about the Exodus. In the play, Moses has a dream:

I dreamt there was on the summit of Mt. Sinai

a certain great throne extending up to heaven’s cleft,

on which there sat a certain noble man

wearing a crown and holding a great scepter

in his left hand. With his right hand

He beckoned to me, and I stood before the throne.

He gave me the scepter and told me to sit

on the great throne. He gave me the royal crown,

and he himself left the throne.

I beheld the entire circled earth

both beneath the earth and above the heaven,

and a host of stars fell on its knees before me;

I numbered them all,

They passed before me like a squadron of soldiers.

Then seized with fear, I rose from my sleep.16

The figure on Mt. Sinai who vacates his throne for Moses can only be God. If Moses sits on God’s throne, then he is in some sense conceived of as divine. While the dream is part of a literary work, there can be little doubt that it reflects wider traditions about Moses. These traditions are also apparent in the Life of Moses by the first-century C.E. philosopher Philo, also an Alexandrian Jew. In Exodus 7:1, God tells Moses: “I have made you a god to Pharaoh.” Philo correspondingly writes that “Moses was named god and king of the whole nation” (Life of Moses 1.55–58).17 It has been suggested that “god” in this passage is an allegorical equivalent for “king,”18 but the choice of the term “god” can hardly be incidental. While Philo insisted that “He that is truly God is one,” he also recognized other divine entities, such as the Logos, that existed under God.

Another case of qualified divinization concerns the Davidic messiah. The notion that the Davidic king was the son of God is well established in the Hebrew Bible in 2 Samuel 7:14 and in Psalm 2:7. It was only natural then that the coming messianic king should also be regarded as the Son of God. The Florilegium from Qumran (4Q174) explicitly interprets 2 Samuel 7:14 in a future, messianic, sense: “I will be a father to him and he will be a son to me. He is the Branch of David, who will arise … at the end of days.” A fragmentary Aramaic text (4Q246), popularly known as “The Son of God Text,” predicts the coming of a figure who will be called “Son of God” and “Son of the Most High”; this figure is probably the Davidic messiah, though some scholars dispute this interpretation.19 To say that the king was the son of God, however, does not necessarily imply divinization. Israel, collectively, is called God’s son in the Book of Exodus and again in Hosea, and the “righteous man” is identified as God’s son in the Wisdom of Solomon, a first century C.E. Jewish text from Alexandria. There are other traditions, however, that suggest a more exalted status for the messianic king.

Rabbi Akiba is said to have explained the Plural “thrones” in Daniel 7:9 as “one for God, one for David.”20 In the Psalms, traditionally attributed to David, there seems to be a clear scriptural warrant for the enthronement of the messiah: “The Lord said to my Lord, sit at my right hand” (Psalm 110:1). In fact, however, the first messianic interpretation of this text is found in the New Testament (Mark 12:35–37; Acts 2:34–36). In the Similitudes of Enoch, the Son of Man figure is also called “messiah,” although he does not appear to have an earthly career. Another Jewish apocalyptic, 4 Ezra, written at the end of the first century C.E., interprets Daniel’s “son of man” vision in terms of a figure who rises from the sea on a cloud, takes his stand on a mountain and defeats the Gentiles in the manner of the Davidic messiah. This figure is also called “my son” by God. The Similitudes and 4 Ezra are witnesses of a tendency to conceive of a quasidivine messiah in Jewish texts of the first century C.E.

A final example of exalted humanity involves a very fragmentary text from Qumran (4Q491), in which the speaker claims to have “a mighty throne in the congregation of the gods” and to have been “reckoned with the gods (elim).”21 We cannot be sure who the speaker is supposed to be; suggestions have ranged from the Teacher of Righteousnessc to some later sectarian teacher to the messianic High Priest. It does seem clear, however, that the speaker is not an angel or other heavenly creature but an exalted human being. It is not unusual in hymns from Qumran for the hymnist to claim that he enjoys the fellowship of the heavenly host, but this text seems to claim a higher degree of exaltation. Once again, we find that a human being could be reckoned among the elim or gods. Even in a conservative Jewish community like Qumran, such an idea was not taboo.

Wisdom and Logos

Our third category of quasi-divine being or entity is the personification of Wisdom, who was identified with the Greek philosophical concept of Logos (Word or Reason) in the Hellenistic period. According to Proverbs 8:22, “God created [the female figure Wisdom] at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of long ago,” and she then accompanied him in the creation of the world. In the Book of Ben Sira, written in the early second century B.C.E., Wisdom increasingly resembles the Creator: “I came forth from the mouth of the Most High, and covered the earth like a mist. I dwelt in the highest heavens, and my throne was in a pillar of cloud. Alone I compassed the vault of heaven and traversed the depths of the abyss” (Wisdom of Ben Sira 24:3–5). According to the Wisdom of Solomon, written around the turn of the era in Alexandria, Wisdom brought Israel out of Egypt and holds all things together. Ben Sira’s statement that Wisdom came forth from the mouth of the Most High already hints at the identification of Wisdom with Word, which is made explicit in the Wisdom of Solomon.

The Word, or Logos, had another set of connotations in Greek philosophy. The Stoics conceived of the Logos as an immanent god—the principle of rationality in the world—and as a kind of world soul. (It can also be called Spirit or Pneuma, although it is understood as a fine material substance.) The Jewish philosopher Philo adapted this concept of the Logos for a Jewish theology that acknowledged a transcendent creator God.22 For Philo, the Logos is “the divine reason, the ruler and steersman of all” (On the Cherubim 36) and it stands on the border that separates the Creator from the creature (Who Is the Heir 2–5). But this Logos is also said to be a god. In his Questions on Genesis, Philo asks: “Why does [Scripture] say, as if of another God, ‘In the image of God He made man’ and not ‘in His own image’? Most excellently and veraciously this oracle was given by God. For nothing mortal can be made in the likeness of the Most High One and father of the universe, but only in that of the second God, who is His Logos.” Here Philo unabashedly calls the Logos a “second God,” and this is not the only passage in which he gives the title “God” to the Logos,23 though he also refers to it as an angel or as God’s first-born son.

Does Philo then believe in two Gods? He addresses this question explicitly in his treatise On Dreams 1.227–229, where he comments on a passage in the Greek Bible that reads “I am the God who appeared to thee in the place of God” (Genesis 31:13). Philo writes:

And do not fail to mark the language used, but carefully inquire whether there are two Gods; for we read “I am the God that appeared to thee,” not “in my place” but “in the place of God,” as though it were another’s. What then are we to say? He that is truly God is one, but those that are so called by analogy are more than one. Accordingly the holy word in the present instance has indicated Him Who truly is God by means of the articles, saying “I am the God,” while it omits the article when mentioning him who is so called by analogy, saying “who appeared to thee in the place” not “of the God” but simply “of God.”24

Philo does not seem to regard the use of “God” as a designation for the Logos as improper,25 although he clearly distinguishes between the supreme God and the intermediary deity

So was Judaism monotheistic in the Hellenistic period? The evidence we have reviewed comes from two areas of Judaism, apocalyptic circles in Palestine, including but not limited to the Dead Sea sect, and the Hellenized Alexandrian Judaism of Philo. Not all Jews shared these ideas and beliefs, but they, are, nonetheless, indisputably Jewish.

In this literature, the supremacy of the Most High God is never questioned, but there is considerable room for lesser beings who may be called “gods,” theoi or elim. Moreover, both the authors of the apocalyptic literature and Philo single out one preeminent divine or angelic being under God—a super-angel called by various names in the apocalyptic texts and identified as the Logos by Philo.

It is often said that the practice of monotheism is shown in Jewish worship, which was reserved for the Most High God and did not extend to lesser divinities or angels. It is certainly true that the official sacrificial cult in Jerusalem was monotheistic, and no evidence indicates that any being other than the God of Israel was worshiped in synagogue services. There is some evidence, however, for the veneration of angels.26 Christian authors such as Clement of Alexandria and Origen claimed that Jews worshiped angels, and both apocalyptic and rabbinic texts prohibit the worship of angels. Presumably, the prohibitions would not have been necessary if the practice had been unknown. There is also some evidence for the practice of calling on angels in prayer, especially in the context of magic. None of this, however, implies that there was an organized, public cult of angels or that the religious authorities sanctioned such activities.

More significant for our purposes is the kind of honor bestowed on the “one like a son of man,” in Daniel 7, who is given “dominion and glory and kingship, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him” (Daniel 7:14). Similarly, in the Similitudes of Enoch we are told that “all those who dwell on the dry ground will fall down and worship” before that Son of Man (1 Enoch 48:5). The passage continues, however, by stating that they will bless, praise and celebrate with psalms the name of the Lord of Spirits—so there is some doubt as to whether the worship is directed at the Son of Man or the Lord God. According to the “Son of God Text” from Qumran, when war ceases on earth, all cities will pay homage either to the “Son of God” or to “the people of God.” Although the homage in this passage involves political submission, worship in the ancient world was often considered analogous to submission to a great king.

Both the “Son of Man” passages and the “Son of God Text” are eschatological: They describe the future; they do not imply that there was any actual cult of either the “Son of Man” or the “Son of God.” But they do suggest that some form of veneration or homage could be directed to these figures in the eschatological future.27 Each of these figures, to be sure, can be understood as God’s agent or representative, so that homage given to them is ultimately given to God. But these passages also show that the idea of venerating God’s agent, at least in the eschatological future, was not unthinkable in a Jewish context.

Was Christianity Monotheistic?

The veneration of Jesus by his first-century C.E. Jewish followers should be somewhat less surprising in light of the foregoing evidence. Those who believed that Jesus was righteous and justly executed would naturally believe that he was exalted to heaven after his death. But more was at issue in the case of Jesus. He was crucified as King of the Jews, which means that he was viewed by the Romans as a messianic pretender and, presumably, by some of his followers as a messianic king. In Luke 24:19, the disciples talk “about Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and leaders handed him over to be condemned to death and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel.” Their bewilderment over Jesus’ death is then relieved by the belief that he has risen from the dead.

Whatever the nature of the resurrection experience, it is undeniable that the belief in it arose very shortly, after Jesus’ death. The resurrection was taken as confirmation that Jesus was indeed the messiah, even though he had not restored the kingdom to Israel, as some had hoped. According to Paul, Jesus was “declared [or appointed?] to be Son of God with power according to the spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead” (Romans 1:4). Although Jesus had unfinished business as messiah, this anomaly was explained by appeal to Daniel 7: Jesus was the “one like a son of man” who would come again on the clouds of heaven. Like the Similitudes of Enoch, the Gospel of Matthew envisions the Son of Man, Jesus, seated on a throne of glory and presiding over the Last Judgment (see Matthew 25:31). In the Gospels, Jesus is said to have spoken of himself as the Son of Man who would come on the clouds of heaven, but it is more likely that he was so identified by the disciples after his death, when he was no longer present on earth.

According to the Gospel of John, the claim that Jesus was Son of God was blasphemous to his Jewish contemporaries: “We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God” (John 19:7). Despite this statement, the claim to be the son of God was not inherently blasphemous in a Jewish context. In the Wisdom of Solomon, it is the righteous man who claims to be the child of God and boasts that God is his father (Wisdom of Solomon 2:13, 16). To claim to be the son of God, in a Jewish context, was not to claim to be equal to God. Nor was it blasphemous to claim that someone was the messiah, the promised heir to the Davidic line. According to Jewish tradition, the great Rabbi Akiba hailed the revolutionary Simeon Bar Kokhba as the messiah, about a century after Jesus. Rabbi Akiba proved to be mistaken, but he was not deemed a heretic. Some Jews apparently believed that the Son of Man, and later the exalted Metatron, was the human patriarch Enoch exalted to heaven. Even the extreme claim of the Gospel of John that the Word was God could be defended in a Jewish context by appeal to Philo’s distinction between the analogical use of “God” without the article, which could refer to the Logos, and “the God,” with the article, which was reserved for the Most High (although it is by no means clear that the author of John’s gospel intended such a distinction).

Nonetheless, the claim in the Gospel of John that “the Father and I are one” is without parallel in Judaism.28 By the end of the first century C.E., the exaltation of Jesus had reached a point where it was increasingly difficult to reconcile with Jewish understandings of monotheism.

The apocalyptic understanding of Jesus reaches its New Testament climax in the Book of Revelation. There John sees “one like a Son of Man, clothed with a long robe and with a golden sash across his chest. His head and his hair were white as white wool, white as snow; his eyes were like a flame of fire” (Revelation 1:13–14). The figure in question, Jesus, combines attributes of both the “one like a son of man” and the “Ancient One” of Daniel 7.29 He has become difficult to distinguish from the God of Israel.30

In some part, the tendency to identify Jesus with the God of Israel began with early Christians attempting to claim for Jesus everything that Jews would claim for an intermediary figure.31 But then it went further; Jesus was the Son of God in a unique sense, and this claim was expressed in Hellenistic idiom in stories of his birth from a virgin. Revelation 12 relates a fragment of a Jewish myth in which the archangel Michael does battle with a dragon in heaven, a variant of a combat myth that was widespread in the ancient Near East. In Revelation, however, we are told that it is by the blood of the Lamb (the crucifixion of Jesus) that the dragon is defeated (Revelation 12:11).32 Michael fights the battle, but Jesus gains the victory. Similarly, the Epistle to the Hebrews is at pains to insist that Jesus is superior to the angels: “For to which of the angels did God ever say ‘You are my son; today I have begotten you?’” (Hebrews 1:5). Hebrews even applies to Jesus the statement of Psalm 110:4, “you are a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek” (Hebrews 5:6), even though Jesus of Nazareth was not a priest at all. Again, if Hellenistic Judaism Venerated the Logos, or Word, as “a second God,” the Gospel of John goes one better by claiming that Jesus is the Word and the Word is God.d

This proliferation of honorific titles and claims made on Jesus’ behalf by the early Christians goes hand in hand with the veneration, or worship, of Jesus in the early Church. Paul declared that “at the name of Jesus every knee should bend in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Philippians 2:10–11). In Revelation, we find the same blessing addressed to the Lamb (Christ) as to “the one seated on the throne” (God): “blessing and honor and glory and might forever and forever” (Revelation 5:13). Now, Revelation pointedly rejects the worship of angels; and John is rebuked twice for prostrating himself before an angel (Revelation 19:10, 22:9).33 Yet Christ has many angelic features in Revelation (especially if the “Son of Man” in Revelation 14:14 is identified as Christ).34 Moreover, the homage paid to Christ in Revelation is reminiscent of the homage paid to the super-angelic Son of Man in Daniel 7: dominion and glory and kingship, so that all peoples, nations and languages should serve him.

The notion that there was a second divine being under God was not intrinsically incompatible with Judaism, although the belief that Jesus of Nazareth was such a being undoubtedly seemed preposterous to many Jews. What was incompatible with Judaism was the idea that this second divine being was equal to God. Hence the argument attributed to the Jews in the Gospel of John: According to Jewish law, Jesus ought to die, for he made himself equal to God. Indeed, in the Gospel of John, Jesus is said to claim unabashedly that “the Father and I are one” (John 10:30). Yet this very formulation shows something of the peculiarity of the Christian confession. Jesus is not “a second God” like Philo’s Logos; he is one with the Father, so that those who worship both Father and Son can still claim that they worship only one God.

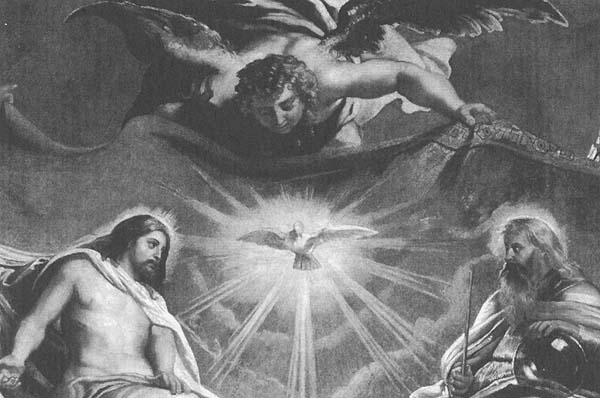

Eventually, Christian theology would be further complicated by the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, which also has its roots in the New Testament and even in pre-Christian Judaism. Over the next few centuries, Christian theologians would labor to find acceptable formulas that would enable them to affirm the divinity of Jesus and the Spirit, but still maintain the unity of God. Along the way, several formulas were rejected as heretical. In the second century C.E., Justin Martyr, following in the footsteps of Philo, spoke of the Logos as “another God” beside the Father; he added that the Logos was other “in number, not in will,” and proposed the analogy of one torch lit from another suggesting different manifestations of the same divine entity.35 This position led to the Monarchian controversy about the unity of God. The Monarchians adopted the position that the Father and Son are one and the same, two aspects of the same being.e A century and a half later, an Alexandrian presbyter named Arius ignited one of the great controversies of Christian antiquity by teaching, in the tradition of Philo, that the Logos was part of the created order and thus was not God in the same sense as the Father. The Council of Nicea, convened by the emperor Constantine in 325 C.E., condemned Arianism as a heresy, and adopted the creed that the Son is “one in being (homoousious), with the Father” and that the Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son.”36 Even people who signed the decree at the time understood these formulas in different ways, and the controversy continued for several centuries.

In traditional Christian theology, the doctrine of the Trinity is a mystery, which entails an admission that it is not entirely amenable to rational logic and understanding. Non-Christians, and many Christians who lack the appetite for metaphysical reasoning, may be forgiven for thinking that this allows for some equivocation, enabling Christianity to maintain contradictory positions without admitting it. Be that as it may, Christianity has never wavered in its claim to be a monotheistic religion. However the different persons of the Trinity are defined, they are to be understood as falling within the overarching unity of God. The notion that God is three as well as one, however, obviously entails a considerable qualification of monotheism.

Both Judaism and Chnistianity are committed to monotheism, the belief that ultimately there is only one God. Moreover, the break between Christianity and Judaism, particularly in their understanding of monotheistic doctrines, was not as sharp or complete as is sometimes assumed. The Synoptic Gospels can be reconciled quite easily with Jewish understandings of monotheism. The theology of Justin Martyr and Origen, in second-century C.E. Christianity, is not greatly removed from that of Philo, except that the Logos is now believed to be incarnate in the person of Jesus. This was, to be sure, a considerable difference, but the difference lay in the evaluation of a specific historical person rather than in the theological framework of monotheism or di-theism. Philo, for example, could speak of the patriarchs as empsychoi nomoi, or “the laws of God incarnate.”37 0nly gradually did the Christian understanding of Christ and the Spirit evolve to the point where it was incompatible with any Jewish understanding of monotheism, and this process was only finalized in the fourth century C.E. Even the Nicene Creed (325 C.E.) begins with the confession, “I believe in one God.” Despite the logical anomalies of the Trinity, this confession is still repeated in Christian churches to this day.

“In the beginning was the Word” reads the opening verse of the Gospel of John, “and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” In the context of the gospel, it is clear that the Word is identified with Jesus of Nazareth, the charismatic preacher who had been crucified by the Romans some 60 years before the gospel was written. John’s gospel is exceptional in the New Testament for the explicitness of its claim that Jesus was divine. Nonetheless, it is both the culmination of a trend within Judaism and a good indicator of the course Christian theology would take in the following centuries. This development would accentuate the gap between emerging Christianity and Judaism.

By nearly all accounts, at the end of the first century C.E. strict monotheism had long been one of the pillars of Judaism.1