The Religious Reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah

The religious reforms of Kings Hezekiah (727–698 B.C.E.) and Josiah (639–608 B.C.E.) of Judah occurred at a time when other Near Eastern civilizations were also carrying out reforms aimed at reviving classical beliefs and traditions.1

In Egypt, one manifestation of this neoclassical spirit is the so-called Shabaka Stone. Pharaoh Shabaka (716–695 B.C.E.) ruled during the XXVth Dynasty, while Egypt was under the domination of Nubia (southern Egypt and the Sudan today). Nubia had long been heavily Egyptianized, and the Nubians promoted traditional Egyptian values derived from the cult of Amun, established by Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.E.) in the upper Nile. Shabaka is said to have discovered a stone with text copied from an ancient papyrus manuscript—“a work of the ancestors which was worm-eaten, so that it could not be understood from beginning to end.”2 The original text purportedly contained ancient Memphite theological and cosmological ideas to be revived and promulgated in eighth- and seventh-century B.C.E. Egypt.

The recovery of the Shabaka Stone has a curious parallel in Judah, where another ancient document was found and used to propagate an older, more traditional set of religious beliefs. During the reign of Josiah, according to 2 Kings 22:8, the priest Hilkiah found a book containing Mosaic teachings “in the house of Yahweh,” the Jerusalem Temple. King Josiah is reported to have used this “book of the Torah”—which many scholars believe to have been an early form of the Book of Deuteronomy—as the basis of his religious reforms. It is Deuteronomy, and the literature associated with it, that provides our earliest textual evidence of a developed monotheism.

The Deuteronomic Revolution

In Judah, this international neoclassicism expressed itself in an ongoing reform movement that waxed and waned from the late eighth to the early sixth centuries B.C.E. This movement peaked during the reigns of Hezekiah and Josiah and left its permanent expression in the Deuteronomic literature (the Book of Deuteronomy plus the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings). According to 2 Chronicles 29–32, Hezekiah began his reform in the first year of his reign; motivated by the belief that the ancient religion was not being practiced scrupulously, he ordered that the Temple of Yahweh be repaired and cleansed of niddâ (impurity). After celebrating a truly national Passover for the first time since the reign of Solomon (2 Chronicles 30:26), Hezekiah’s officials went into the countryside and dismantled the local shrines or “high places” (bamot) along with their altars, “standing stones” (masseboth) and “sacred poles” (’a

Israelite Monarchies in Iron Age I (1000–586 B.C.E.)

| United Monarchy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| David | c. 1000–961 | ||

| Solomon | c. 961-92l | ||

| Divided Monarchy | |||

| Kingdom of Judah | Kingdom of Israel | ||

| Rehoboam | 921–913 | Jeroboam I | 921–910 |

| Abijam (Abijah) | 913–911 | ||

| Asa | 911–869 | ||

| Nadab | 910–909 | ||

| Baasha | 909–886 | ||

| Elah | 886–885 | ||

| Zimn | 885 | ||

| Jehoshaphat | 872–848 | ||

| Omri | 885–874 | ||

| Ahab | 874–853 | ||

| Ahaziah | 853–852 | ||

| Jehoram | 854–841 | Joram | 852–841 |

| Ahaziah | 841 | ||

| Athaliah | 841–835 | Jehu | 841–814 |

| Jehoash | 835–786 | Jehoahaz | 814–798 |

| Amaziah | 796–790 | Joash | 798–782 |

| Jeroboam II | 793–753 | ||

| Uzziah (Azariah) | 790–739 | ||

| Zachariah | 753–752 | ||

| Shallum | 752 | ||

| Jotham | 750–731 | Menahem | 752–742 |

| Pekahiah | 742–740 | ||

| Ahaz | 735–715 | Pekah | 740–732 |

| Hoshea | 732–723/722 | ||

| Hezekiah | 727–698 | ||

| Manasseh | 696–641 | ||

| Amon | 641–639 | ||

| Josiah | 639–608 | ||

| Jehoahaz | 608 | ||

| Jehoiakim | 608–598 | ||

| Jehoiachin | 598–597 | ||

| Zedekiah | 597–586 | ||

The account of Hezekiah’s reform activities in 2 Kings 18:1–8 is much briefer. Although he is credited with removing the high places, the major reform is credited to Josiah (2 Kings 22:3–23:25). Since Chronicles is a much later source than Kings—and, in fact, often draws openly on both the narrative and language of Kings—historians normally give preference to Kings over Chronicles when there is a discrepancy between them or a difference of emphasis. But in this case there are good reasons to accept the viewpoint of the Chronicler. The Kings account was probably written by a historian commissioned by Josiah,3 who would have emphasized the contribution of his royal patron. Archaeology, moreover, has shown that many of the civil and political changes associated with the centralization of the cult in Jerusalem probably took place during Hezekiah’s reign, when Jerusalem itself underwent a major expansion. Nahman Avigad’s 1970 excavation in the Jewish Quarter, for example, exposed a 20-foot-thick wall dating to this period evidently the new wall Hezekiah built outside the old city wall (2 Chronicles 32:5). This westward expansion of the city must have been intended, at least in part, to accommodate refugees from the fall of Samaria (Israel) to the Assyrians in 721 B.C.E; and the wall discovered by Avigad must have been built in anticipation of Sennacherib’s 701 B.C.E. invasion, as the Chronicles account makes clear. The vitality of Hezekiah’s administration is further illustrated by excavations throughout Judah.4

Thus archaeology provides evidence of a burgeoning, centralized Judahite state during the period of the reforms reported in Kings and Chronicles, and it shows that the centralization began with Hezekiah. But it does not provide direct evidence of religious reform activities, which are much harder to identify in the archaeological record.

When, for example, were the high places removed? On this score, there is little reason to doubt the biblical account that they were dismantled during the reigns of both Hezekiah and Josiah. We even have some archaeological evidence. At Arad, in the Negev desert, excavator Yohanan Aharoni found a small temple that seems to have been roughly contemporary with Solomon’s Temple. This discovery, along with the recovery of sacrificial altars from other Judahite sites such as Beersheba, shows that animal sacrifice was indeed offered at high places (bamot) during the period before the reforms. According to Aharoni, the altar of the Arad temple went out of use at the end of the eighth century B.C.E. and the entire shrine was abandoned late in the seventh century B.C.E.—changes that Aharoni attributed to the reforms of Hezekiah and then Josiah. Although reevaluation of the archaeological evidence from Arad suggests that the temple continued in use during the final phase of the fortress (the early sixth century B.C.E.), there remain indications that the temple was dismantled before the destruction of the site. The temple’s two small altars, probably for burning incense, were carefully laid on their sides and covered with plaster, apparently in an attempt to cancel out Arad’s high place in the course of Josiah’s reform.

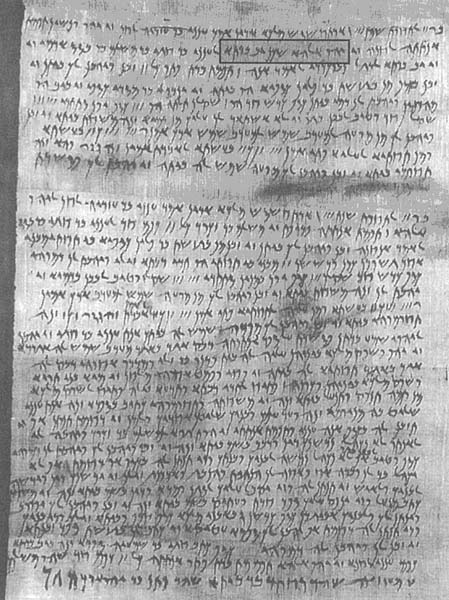

This elimination of local places of worship is very important to the early development of Jewish monotheism. On the surface, the issue at stake seems be purely cultic, having much to do with where and how the god of Israel should be worshiped and little to do with his divine nature. But another aspect of the matter deserves consideration. Once again, archaeology has supplied essential information—in the form of eighth-century B.C.E. Hebrew inscriptions found at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, on the Sinai peninsula. Before the discovery of these inscriptions, we had no prereform-period Hebrew text with any extensive religious content. When the ‘Ajrud materials were read, however, they proved to be substantially religious in content, and they have provided important information about pre-reform Israelite religion during the Iron Age, much of which we have only begun to appreciate. Especially significant for the issue of cult centralization is the fact that in the ‘Ajrud texts the God of Israel is not referred to simply as Yahweh but, in every unbroken context, as “Yahweh of GN” (with GN standing for a geographical name). In particular, we have “Yahweh of Samaria” (yhwh s

“Yahweh of Samaria” and “Yahweh of Teman” belong to a category of divine name well known outside Israel. These names take the form “DN of GN,” where DN is a divine name or national god and GN is a geographical name, designating a particular local shrine or temple where the god or goddess was worshiped. The great Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, for example, had principal cult centers in the Assyrian cities of Nineveh and Arbela. Although every pious Assyrian knew there was only one Ishtar, prayers and sacrifices were offered to Ishtar of Nineveh or Ishtar of Arbela. When the Assyrian king Assurbanipal (668–627 B.C.E.) or one of his royal predecessors called upon the Assyrian gods to sanction a treaty, he was careful to invoke both Ishtar of Nineveh and Ishtar of Arbela, as if “Ishtar” alone would have been insufficient. This shows that local manifestations of a god, when approached in the cult for purposes of worship, tended to become quasi-independent.

This was also true concerning local manifestations of Yahweh, as illustrated by an episode in the story of Absalom’s revolt in 2 Samuel 15. Following his murder of his brother Amnon, Absalom flees to the land of Geshur in the modern Golan Heights and then returns to Jerusalem and surrenders to David. After four years of house arrest in Jerusalem, he approaches the king with the following request: “Let me go fulfill the vow I made to Yahweh in Hebron (yhwh bh

Local cults, therefore, had the potential to become powerful and independent even if they were not centers for the worship of foreign gods. The elimination of the high places and the centralization of the cult in Jerusalem put an end to the authority not only of the local priesthoods but also of the local Yahwehs. For this reason, the theology of the Deuteronomic literature is sometimes referred to as “MonoYahwism,” and the danger posed by the quasi-independent local Yahwehs helps explain one of the most important passages in this literature. Deuteronomy 6:4–5 provides the opening verses of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9) in Jewish tradition and the Great Commandment (see Mark 12:29–30) in Christianity:

s

û eá ma‘ yisŒ raµ ’eµ l yhwh ’eá loµ hênû yhwh ’eha µ d weá ’aµ habtaµ ’eµ t yhwh ’eá loµ hêkaµ beá kol-leá baµ beá kaµ ûbeá kol-napsû eá kaµ ûbeá kol-meá oµ deŒ kaµ .

Hear, O Israel! Yahweh our god, Yahweh is one! And you shall love Yahweh your god with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might!

Verse 5, which requires that the Israelites’ religious devotion and energy be directed exclusively towards Yahweh, draws on the common “love” language of ancient Near Eastern political loyalty.6 This is love that can be commanded—political loyalty and exclusive allegiance.

The passage continues in this vein in Deuteronomy 6:13–15:

It is Yahweh your god whom you shall fear, and it is he whom you shall serve, and it is in his name that you shall swear. You shall not go after other gods from the gods of the nations that are around you—since Yahweh your god who is in your midst is a jealous god (’e

µ l qannaµ ’)—lest the anger of Yahweh your god be ignited against you and exterminate you from the land.

The penalty for the worship of other gods is exile—“from the face of the land” (whis

Yahweh exacts this punishment because he is “a jealous god” (’e

You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make yourselves an idol—the form of anything in the sky above or in the earth below or in the waters that are under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I, Yahweh your god, am a jealous god (’e

µ l qannaµ ’), visiting the sins of the fathers upon the sons to the third and fourth generation for those who hate me, and dealing loyally by the thousands with those who love me and keep my commandments.Deuteronomy 5:7–10/Exodus 20:3–6

The meaning of ’e

The issue at stake here is not MonoYahwism. Nor is it exactly what we consider monotheism, the denial of the existence of other gods. What the passages espouse is monolatry—confinement of worship to a single god—which includes a strong component of aniconism, the repudiation of any visual representation of deity. We are thus led to ask, To what extent was Israelite religion before the reform period polylatrous and representational? That is, did Israelites worship many gods and represent them with icons or idols? The easy answer to this question is yes. The biblical writers report that they did, and the archaeological record confirms it. But on closer inspection the answer turns out to be somewhat less straightforward.

The Origins of Monotheism

Older models generally described the origins of monotheism as following an evolutionary pattern. In the 19th century it seemed reasonable to suppose that human religion tended to evolve in stages. It began in primitive societies as a kind of spirit worship, sometimes called polydemonism; with the rise of complex societies, it developed into polytheism, the belief in an organized pantheon of gods; eventually, polytheism was replaced by monotheism, the ideal and perhaps inevitable goal of developed religion. These idealized schemes were discredited in the early 20th century, when anthropologists began to visit so-called primitive societies and to discover that some of them, though at a neolithic stage of material culture, were in fact monotheistic and showed no sign of ever having been anything else.

The history of ancient Near Eastern religions suggests that the same people sometimes see the divine as singular and sometimes as plural. Most monotheistic religions have at least some plural ways of viewing their god—who may act through angels or humans with superhuman powers—and yet remain committed to the belief that there is one god. Similarly, polytheistic religions often find monotheistic expressions. There is an often-cited hymn to the Mesopotamian god Ninurta, for example, in which a worshiper who surely believes in the independent reality of each member of the pantheon nevertheless identifies many of the great gods and goddesses with parts of Ninurta’s body:

Warlike Ninurta …

Your face is Shamash [the sun god],

Your two eyes, lord, are Enlil [the lord of the earth] and Ninlil [his consort] …

The iris of your eye, lord, is … Sin [the moon god] …

The lashes of your eyes are the rays of Shamash.

The form of your mouth, lord, is Ishtar of the stars.

Anu [the god who presides in the divine assembly] and Antu [his consort] are your two lips, your command …

Your teeth are the Sibitti [the seven ruling gods], who overthrow the wicked.

Your two ears, O speaker of wisdom, are Ea and Damkina [god and goddess of wisdom].

Your head is Adad [the rain god], who shapes heaven and earth like a master craftsman.

Or consider this hymn to the goddess Baba, which identifies her with female deities worshiped in different local cults:

In Ur you are Ningal, the sister of the great gods.

In Ekishshirgal … you are Ningiazagga, the protectress of all mankind, the light of the high heavens.

In Sippar, the ancient city, the light of heaven and earth, of gods and men, you are, in [the temple] Eababarra, [the goddess] Aa …

In Ehili, you are Ishtar …

In Babylon, the gathering place of the gods, you are Ninahakuddu.

In Esagila, you are Eru’a, who creates offerings …

Perhaps the best known of these texts is a god-list that identifies the major male deities as aspects of Marduk, god of Babylon, relating to their functions:

| Urash (is) | Marduk of planting. |

| Ninurta (is) | Marduk of the pickaxe. |

| Nergal (is) | Marduk of battle. |

| Zababa (is) | Marduk of warfare. |

| Enlil (is) | Marduk of lordship and consultations. |

| Nabu (is) | Marduk of accounting. |

| Sin (is) | Marduk who lights up the light. |

| Shamash (is) | Marduk of justice. |

| Adad (is) | Marduk of rain. |

Another well-known phenomenon in world religions helps explain how a single god can generate other gods. This is the phenomenon of hypostasis, according to which some property of a deity, such as his anger or wisdom or cultic presence, is considered an entity in itself and in some cases is personified. In biblical and early postbiblical Judaism and in early Christianity, the wisdom of God is hypostatized. Thus in Proverb 9:1–4a the h

Wisdom has built her house,

she has hewn her seven pillars,

She has slaughtered her animals, mixed her wine.

Yes, she has set her table.

She has sent out her young women,

she calls from the rooftops of the city,

“Whoever is foolish, turn aside here!”

Lady Wisdom is very prominent in Jewish literature; we encounter her in Proverbs 1–9, Job 28, Wisdom of Ben Sira 24 and the Wisdom of Solomon. In early Christianity, she was known by her Greek name, Sophia. In Gnostic texts, she appears as the mother or consort of a number of divine beings. In non-Gnostic Christianity, she is linked closely with Jesus Christ, in a male-female complimentarity that recalled her origin as an aspect of God. This is expressed iconographically in a painting on the doorway of the catacomb of Karmouz at Alexandria, where an angel with wings is designated “Sophia Jesus Christ.” Similarly, one of a pair of Coptic reliquary crosses displaying identical figures is labeled “Jesus Christ,” while the other is labeled “Mother Christ.” In the great church of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and elsewhere, Wisdom was subsumed under the representation of Mary, as shown by her portrayal in the apse of Santa Sophia in Kiev. In a 14th-century tapestry, Mary is depicted as Athena, the wise goddess who sprang fully grown from the head of Zeus; she and her suppliant wear similar crowns, and the book they both hold is an invincible shield illustrating the text of Wisdom of Solomon 7:30: “Against Wisdom evil does not prevail.” Almost the same iconography appears in Jan Van Eyck’s elegant portrait of Mary as Lady Wisdom in the Ghent Altarpiece.

Except in Gnosticism, the hypostatization of Lady Wisdom in Judaism and Christianity probably never reached the point where she was fully personified as a goddess. This is not true, however, in other ancient cases of hypostasis. In the fourth-century B.C.E. Jewish colony on Elephantine Island in Upper Egypt, for example, Yahweh—or Yahu, as they called him—was worshiped under the surrogate name Bethel, or “House of God.” Offerings were made, however, not only to Yahu or Bethel but also to at least three other deities whose names originally denoted aspects of the cultic presence of Yahu: Herem-Bethel (“the Sacredness of Bethel,” that is, “the Sacredness of Yahu”), Eshem-Bethel (“the Name of Bethel”) and Anath-Bethel, also called Anath-Yahu. The last name probably means “the Sign of Yahu,” that is, the visible sign of the cultic presence of Yahu. In Elephantine Judaism, then, at least three aspects of Yahweh—his Sacredness, his Name and his Active Sign—were hypostatized, personified and worshiped as deities.

The evidence from the history of religions suggests, therefore, that polytheism and monotheism are not ideal, exclusive religious patterns, and that the development of one into the other cannot be predicted, though it can be observed and described. Nor does Jewish monotheism seem to have arisen out of a form of polytheism similar to that which prevailed in Mesopotamia or in Late Bronze Age Syria and Canaan. Instead, at the beginning of the Iron Age (around 1200 B.C.E.), a different religious pattern appeared among the new and larger nation-states that emerged in Syria-Palestine.

In the religions of the Late Bronze Age (about 1550–1200 B.C.E.), each city-state seems to have had a principal deity—like Ba‘al Zaphon of Ugarit—who was preeminent in the esteem of the citizens and whose favor and protection were regarded as essential to the welfare of the state. This deity, however, was perceived as only the foremost of a number of deities—some of whom had their own temples standing alongside that of the major god. In the religions of the new Iron Age nation-states, on the other hand, the preeminent city god was replaced by a supreme national god, who, as far as our evidence permits us to say, was almost the sole object of worship in the community.

We know the names of these national gods from the Bible and from epigraphic materials found in Israel, Jordan and Syria. They included, among others, Milcom the god of Ammon, Chemosh the god of Moab, Qos the god of Edom and Yahweh the god of Israel. A theological rationale for the division of the land into nation-states worshiping national gods is recorded in Deuteronomy 32:8–9, the original form of which is preserved in the Greek Bible and a manuscript from Qumran:

When the Most High apportioned the nations,

when he divided up the sons of man,

He established the boundaries of the peoples,

according to the number of the sons of God.

The allotment of Yahweh was his people,

Jacob was his portion of the estate.

And we can add that the Ammonites were the allotment of Milcom, the Moabites the allotment of Chemosh and so on.

As Israelite religion developed at the close of the Iron Age, and then passed through the extraordinary period of religious creativity that transformed it from pre-Exilic Yahwism into early Judaism, the Most High God of Deuteronomy 32:8 was exclusively identified with Yahweh. And with the emergence of Jewish monotheism, the power of the other gods, and eventually their very existence, was denied.

But even within the earlier nation-state formulation of the Iron Age, official Israelite religion showed little interest in other gods or goddesses. In the onomastic records from that period— that is, the lists of surviving personal names—citizens of Israel and its neighboring nation-states bore names that commonly included as a theophoric element the name of their national god or the generic name ’e

Yahweh and His Asherah

The predominant pattern of Iron Age religion in the nation-states of Syria-Palestine was, if not truly monotheistic, at least monolatrous—confining worship to a single god—and henotheistic—viewing the world in terms of the will of a single god without necessarily denying the existence of others. But if in the Iron Age the worship of a single god had already become predominant, what is the point of the “jealous god” motif of Deuteronomy and the reform movements? The injunction against worshiping foreign gods is clear enough, insisting on sole allegiance to the national god. But the principal stricture in the “jealous god” passage involves the prohibition of cultic representations, or idol worship; and the accounts of Hezekiah’s and Josiah’s reform activities stress not only the removal of high places, but also the destruction of masseboth and ’a

Masseboth, we know, are standing stones erected to signify divine presence.b But what is an asherah?

The term “asherah” appears many times in the Bible. In 1 Kings 15:13, we are told that the eighth-century B.C.E. king Asa deposed his mother, Maacah, as Queen Mother of Judah “because she had made a miples

But that assumption is probably wrong, given the monolatrous character of pre-reform Yahwism. A more likely explanation is suggested by the inscriptions and graffiti discovered at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. A number of these texts contain divine blessings invoked “by Yahweh … and his asherah” (lyhwh … wl’s

So we return to the idea of hypostasis, in which abstract aspects of a god are attributed concrete substance and worshiped as partly or entirely independent deities. As is common among the religions of ancient Syria and Canaan, some abstract aspect of a god might be attributed substantial form and personified as female. Thus there was a group of female deities who seem to have arisen as hypostatic forms of leading male deities. Each of these goddesses was given an epithet that identified her as the Face or Name of the god, that is, as his cultic presence. Thus in the Late Bronze Age, for example, the Ugaritic goddess Ashtart was called “Name-of-Ba‘al” (’t

The male deity is the community’s chief god, whose favor and sustenance are essential to its welfare. The female deity is the male deity’s consort, but she arises as a hypostatic form of his Face or Name, that is, of his cultic presence. The religious issue is that of cultic presence and availability, an issue classically expressed in the study of religion as the theological problem of divine transcendence and immanence. How can a great god, who transcends the ordinary world, be said to be immanent in an earthly temple? Solomon expressed the anxiety associated with this problem in his prayer dedicating the Temple: “Will a god really dwell on earth? The heavens and the heavens’ heavens cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built!” (1 Kings 8:27). The solution offered in 1 Kings is that although Yahweh will continue to dwell in heaven, his Name will dwell in the Temple in Jerusalem. When prayers and petitions are brought to Yahweh’s Name on earth, Yahweh himself will hear them in heaven. Solomon expresses this idea in the continuation of his prayer:

Turn your face towards your servant and his supplication, O Yahweh my god, hearing the cry and the prayer that your servant is praying in your presence today, so that your eyes may be open to this house night and day and to this place of which you have said, “Let my name be there!” so that you might hear the prayer that your servant prays in this place. Hear the cry of your servant and your people which they pray in this place, so that you might hear in your dwelling place in heaven, and hearing forgive.

1 Kings 8:28–30

We do not know how far the hypostatization, personification and deification of the divine presence went in ancient Israel. In the Bible, the Name and Presence of God are given hypostatic form, but they are not personified except, notably, in the form of mal’a

Yahweh’s asherah, as known from the inscriptions “to Yahweh and his Asherah” on pithoi from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, should be understood in the same way as the Anath-Yahu of Elephantine Judaism or the Name and Face of Ba‘al goddesses of the Phoenician and Punic world. The verb from which the Hebrew word ’a * t

* t

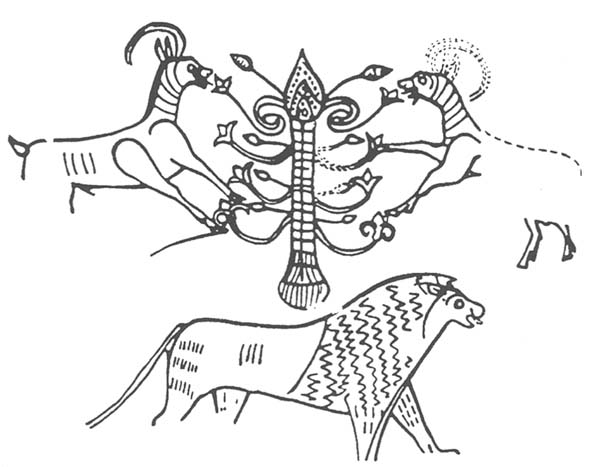

On one pithos from Kuntillet ’Ajrud, two figures are depicted in the foreground. Some scholars have interpreted these figures as a pair of representations of the Egyptian god Bes. But that is not so; the figures in fact represent Yahweh and his Asherah, as the blessing written over the depiction suggests. This is the Samarian Yahweh, depicted in human form with a bull’s head, hooves and a tail—the “Young bull of Samaria” condemned in Hosea 8:5–6 and elsewhere. His Asherah, who also has bovine horns, hooves and a crown, stands alongside him in the conventional position of the consort in, for example, Egyptian art. She is a goddess, but she is a Yahwistic goddess, not a Canaanite goddess. She represents Yahweh’s presence, just as the wooden pole that she personifies represents it in his shrine. It was this iconography that the Deuteronomic reforms deplored and attempted to eradicate: the representation of Yahweh as a bull, the representation of his available presence as a goddess and the cultic representation of both by masseboth and ’a

These changes, together with the eradication of local places of worship and the revival of Israel’s ancient distrust of foreign gods, led to an aniconic and nonlocalized form of Yahwism. In turn, this form of Yahwism led, in the years of the Exile and thereafter, to the development of a more abstract and rigidly aniconic form of monotheism than the Israelites had known in the pre-reform period.

The religious reforms of Kings Hezekiah (727–698 B.C.E.) and Josiah (639–608 B.C.E.) of Judah occurred at a time when other Near Eastern civilizations were also carrying out reforms aimed at reviving classical beliefs and traditions.1

In Egypt, one manifestation of this neoclassical spirit is the so-called Shabaka Stone. Pharaoh Shabaka (716–695 B.C.E.) ruled during the XXVth Dynasty, while Egypt was under the domination of Nubia (southern Egypt and the Sudan today). Nubia had long been heavily Egyptianized, and the Nubians promoted traditional Egyptian values derived from the cult of Amun, established by Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.E.) in the upper Nile. Shabaka is said to have discovered a stone with text copied from an ancient papyrus manuscript—“a work of the ancestors which was worm-eaten, so that it could not be understood from beginning to end.”2 The original text purportedly contained ancient Memphite theological and cosmological ideas to be revived and promulgated in eighth- and seventh-century B.C.E. Egypt.