The Exodus from Egypt: Myth or Reality?

If you think the issue of the Israelite settlement is tough, it’s nothing compared to the Exodus. Now the Exodus, that’s a real tough one. We are very fortunate today to have with us to discuss the Exodus, Baruch Halpern. Baruch Halpern is a major younger scholar. He is not yet 40 years old. He has been at York University in Canada, but has just accepted a professorship at Penn State University in Pennsylvania, where he will form a whole new department of religious studies. All of today’s speakers, except myself have their Ph.D.’s from Harvard. Maybe that’s not so good, we are bringing you a Harvard perspective. Baruch graduated summa cum laude and his Ph.D. dissertation was accepted with highest honors. If I were to read Baruch’s curriculum vitae we would be here all day. He is the author of several important scholarly books, one called The Constitution of the Monarchy in Israel, another entitled The Emergence of Israel in Canaan and still another called The First Historians. He is widely known as a brilliant and insightful speaker, as well as a writer. I’m sure you’ll enjoy him and learn from him. It’s a pleasure to introduce my friend Baruch Halpern.—H.S.

Thank you very much. Hershel began his talk with the comment that you could accept whatever he said unequivocally. I wish I could say the same thing about his introduction. (Laughter.)

Under what circumstances did Romulus and Remus found Rome? What was the role of Hercules, or Jason and the Argonauts, in creating a unified Mycenaean consciousness? If you can answer those questions, you are ready to tackle the issue of the Exodus. For our accounts of the Exodus reflect the prehistory of the Israelite nation, or, perhaps, of some part of it.

The closest parallel to the Book of Exodus in the ancient West is Homer’s Odyssey. Both are stories of migration—of identity suspended until the protagonist—Odysseus or Israel—reaches a home. Neither account records events of the sort that are likely to have left marks in the archaeological record, or even in contemporaneous monuments. At both ends of the journey, though, in Egypt and Israel or at Troy and Ithaca, the narrative can be said to reflect local conditions. In both cases, our sources reflect long-term oral transmission, followed by authoritative codification in writing. In both cases, there is evidence of that peculiar process of oral transmission in which the story is renegotiated with each separate audience each time it is told.1 Each story reflects a healthy admixture of fancy with whatever is being recalled.

The Odyssey is the story of an individual at odds with sorceresses, one-eyed cannibals and sirens—very much like a metaphor for the journey of a social welfare bill through the legislature. The implausibility of the story occasions no great difficulty: Augustine tells us that the Odyssey was taught as gospel in the Greek world of his day; it is basically a piece of children’s literature. So, in its way, is the story of the Exodus.

But the Exodus is not the story of an individual; it is the story of a nation. It is the historical myth of an entire people, a focal point for national identity. The Exodus story was to the ancient Israelite what the stories of the Pilgrims and the Revolutionary War are to Americans. At a deep level, in fact, our American fathers modeled their notions of identity and history on the Exodus.2

The Exodus coded certain common values into the culture. All Israel shared the background of the ancestors—all Israel had been slaves in Egypt. Whatever one’s biological ancestry, to be an Israelite meant that one’s ancestors—spiritual or emotive or collective ancestors—had risen from Egypt to conquer Canaan. YHWHa liberated the Israelites from Egypt and executed a covenant with them. The covenant stipulated that, in return for their emancipation and for the gift of the land of Canaan, Israel would worship YHWH and obey his law. In Near Eastern culture, a sovereign who saved his subjects from ruin and gave them land merited loyalty. This nexus furnished the myth of the Passover, celebrated every spring as the green wheat broke ground. This was the story of how Israel came to be, and how it came into possession of Canaan. For without the conquest of Canaan, the Exodus would have been without a point.

The earliest Israelite Passover ritual already incorporated the pretense that the participants were in transition from Egypt to Israel, from bondage to freedom: The unleavened bread they ate was (and is) the “bread of affliction,” the unleavened bread that their ancestors ate on leaving Egypt. And the roasted lamb they ate was the stuff of rugged campfires; it reflected the absence of basic amenities—since in civilized settings, meat was always boiled.3 The ritual of the Passover, in sum, always presupposed the threshold location of the celebrant, between bondage and freedom, between Egypt and Canaan, in the realm of the uncivilized.

The difference between the early Israelite celebration and the Jewish festival is this: The Jewish celebrant in the Diaspora expresses hopes for national reintegration; the ancient Israelites knew, from the bleatings of the flocks and from the greening of the landscape all around them, that the festival would leave them in possession of the land of Canaan.

Yet modern scholarship divorces the Exodus from its completion in the conquest. For the relation of the Exodus to Israel’s settlement of Canaan is no longer as clear as it was to the Israelites of the Iron Age.b Neither the date of the Exodus nor the duration of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt can now be ascertained with any confidence. Consequently, we cannot accurately gauge the interval between the Exodus and the emergence of Israel in Canaan. More the pity: to the Israelite of the Iron Age, the events were all but simultaneous; this is the reason that the Book of Joshua locates Israel’s entry into Canaan at the time of the Passover (Joshua 4:19, 5:10–11).

The historical uncertainty arises from the nature of our sources, and of the events reported. Endless generations of oral recital have made themselves felt in shaping the literature. The accounts—of J, E, P, D,c and other sources—differ in detail.4 And the story of the Exodus is so central to Israelite identity that changes in that identity almost unconsciously registered in the evolution of the story. Nevertheless, behind the Exodus story events can be discerned that, unlike those of the patriarchal narratives, can be termed historical in scale.

First, to the matter of dates. The Bible basically offers us a choice of various dates for the Exodus. First Kings 6:1 places the building of Solomon’s Temple 480 years after the Exodus, which would put the Exodus around 1450 B.C.E., smack in the reign of Thutmosis III, the Augustus of the Egyptian empire. The Bible also tells us that the Israelites grew from a clan of 72 males to a mighty “mixed multitude” of around 600,000 adult males during their stay in Egypt—the number is from the P source (Genesis 46:8–27; Exodus 1:5, 12:37; Numbers 1:18, 46–47, 26:4, 51). Other sources recall a stay of four generations (Genesis 15:16 [J or RJE]; Exodus 6:16–27 [P]), over the course of which such a population explosion seems implausible; or of 400 years (Genesis 15:13 [RJEP?]; cf. Exodus 12:40–41 [P]).

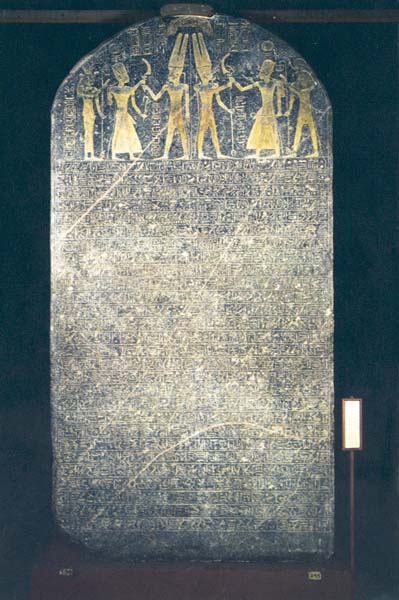

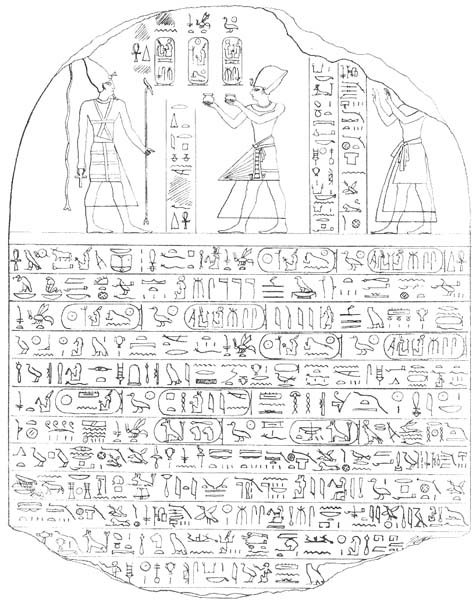

At the end of the sojourn in Egypt, under the pharaoh of the oppression, the Israelites built the store-cities of Ramses and Pithom. Ramses was rebuilt as a capital in the reign of Ramesses II, in the 13th century B.C.E.d The pharaoh of the Exodus, who succeeded the pharaoh of the oppression (Exodus 2:23), and who seems to drown during the Exodus (Exodus 14:6–8, 10, 27–30), would then be Merneptah, Ramesses’ son and successor. Unfortunately, according to a hieroglyphic inscription known as the Merneptah Stele, or the Israel Stele, Merneptah already knew of an Israel living in Asia in the fifth year of his reign, around 1230 B.C.E. Even assuming that the pharaoh of the Exodus didn’t drown, Israel cannot have left in the first year of Merneptah and then wandered in the wilderness for 40 years before turning up in Canaan in his fifth year.

So either one must divorce the Exodus from the conquest, as I shall try to do a bit later on, or one must remove the reference to the store-cities. The alternative, lately in vogue, is to claim that the Israelites built not Ramses, but the town of Avaris, the ancient predecessor of Ramses. But any such activity would have to be located at least 150 years before 1450 B.C.E.—in which case, the pharaoh of the Exodus will not have been the immediate successor to the pharaoh of the oppression.

In short, one or another aspect of the biblical account will have to be jettisoned. Now, the question is, how shall we choose which aspects to retain?

Not so long ago, had you asked my younger daughter what animal she most fervently wished as a pet, she’d have answered, “a unicorn.” The actual evidence concerning the Exodus resembles the evidence for the unicorn. We have replicas, even cuddly reproductions, but we never seem to lay our hands on the real thing. To put it in a different light, what we have are Israelite writings from the Iron Age that reflect back on Egypt and Canaan in the Bronze Age.e So, the first question is, what were Israel’s ideas about Israelite prehistory in the Bronze Age? What did the Israelites know about the Bronze Age, and what role did they think their ancestors played in it? Oddly enough, the way to get at the Exodus is to focus, not on all the contradictory and unstable details in the biblical text, but on the conceptual framework within which the Israelite authors furnished those details.

The place to start is with the Book of Genesis, which tells us that Israel (Jacob)f descended to Egypt in a time of famine and found that his son Joseph, who had been sold into slavery, had risen to be vizier there. Where in Egyptian history does this story belong?

Semitic slaves are attested in Egypt from the beginning of the second millennium on down. The Amarna 1ettersg clarify the context: Whenever warfare or drought wracked Asia, townsmen in Canaan sold their families to Egypt in exchange for grain.5 Sometimes these slaves rose to positions of considerable prominence in Egypt, often to major power.6 The universal experience of Canaanites, in other words, was that in times of famine, Canaanites were sent down to Egypt. And when the Canaanites were pastoralists, it was to the land of Goshen they went—the area where the Israelites settled. This is the background against which the myth of Israel’s descent into Egypt must be viewed.

Earlier, Hershel Shanks remarked on the history of the Hyksos in Egypt. Is the Joseph story set before that time, in the Egyptian Middle Kingdom,h when Semitic immigration into Egypt produced records of Semitic slaves and even Semitic officials in the Delta? At that time, the pharaohs based themselves in Thebes, some 350 miles south of the Nile Delta, so this creates a problem.

Does the Joseph story belong in the Hyksos era, when Semites rose to be nomarchs (kings of districts) and even pharaohs? These were the rulers of the XVth Dynasty;i the Egyptian priest, Manetho,j interprets the term Hyksos7 to mean “shepherd kings.” These Semitic “invaders” of Egypt—the invasion itself may have taken the form of a longstanding immigration into the Delta—expanded from their base in the Delta—at Avaris (Tell ed-Dab‘a on the Pelusiac branch of the Nile)—to control Egypt as a whole for about a century. Ahmose, the founder of the XVIIIth Dynasty, expelled the Hyksos sometime around 1565 B.C.E., and relocated the capital again at Thebes.8 Does the Joseph story belong to the period after that expulsion, the period of the XVIIIth and XIXth Dynasties, when Egypt held sway not only over Canaan but over Asia as far as the Euphrates?

Shanks notes that some scholars have associated Joseph’s rise with the Hyksos. This was the tradition related in antiquity. Manetho, a priest who wrote a history of Egypt in the third century B.C.E., placed Joseph’s entry into Egypt and his rise in the early part of the reign of the Hyksos king, Apophis. The Hyksos were expelled, and then Moses called them back to help the later Israelites escape from Egypt.

To ask whether Manetho corroborates the Joseph story is to invert the actual relationship: Manetho relied on the Bible, probably at secondhand, since he concluded that the Israelites were lepers (cf. Numbers 11) and that Moses was Osarsiph, priest of On (cf. Joseph, who married the daughter, we are told, of a priest of On). Yet the Hyksos interlude impressed itself indelibly in Egyptian memory. Pharaoh Kamose, predecessor of Ahmose who expelled the Hyksos, accused them of widespread destruction, and there are indications of famine in the period.9 Egyptians accused the Hyksos in hindsight of neglecting all the gods but Seth, and of imposing heavy taxes. Manetho echoes these claims, and complains that the Hyksos accumulated grain at their capital Avaris and enslaved the population.

Joseph is said to have imposed a harsh regime of taxation in Egypt to accumulate grain to weather an approaching famine.10 Genesis is suggestive: “To this day,” it claims, Egypt’s peasants have the status of tenant farmers, and must pay 20 percent of their produce to their landlord, the pharaoh (Genesis 47:18–26 [J]). The text thus deflects complaints about Hyksos oppression: Joseph introduced the system in order to avert a worse catastrophe, starvation. Joseph’s name in Egypt reflects this interpretation—resisting any convincing Egyptian etymology, the name should be understood as a portmanteau of Semitic and Egyptian:

saphnat pa-õanhË

, the “cool north wind of life.” Like the north wind relieving the oppressive heat down the Nile Valley, Joseph is the Semite blowing in from the north who gives new life to Egypt.

What’s more, the Bible claims that no subsequent pharaoh has reformed Joseph’s tax. The Egyptian regime in the Iron Age is the legatee of Joseph’s policies. This claim of continuity between Hyksos Egypt and Iron Age Egypt reflects the exposure of Israelite merchants and diplomats to Egyptian culture, as we shall see.

The portrayal of the Israelites as “shepherds” in Genesis is no coincidence either: The Egyptians remembered the Hyksos as “shepherd-kings.” Joseph is introduced as a shepherd, destined to be a ruler.11 The Israelites are associated with herds, and when they enter Egypt are settled in Goshen, based on their belief that it furnishes good pasturage.

Some scholars claim that the location of the Israelite herders falsifies the biblical reports. Goshen was the Wadik Tumilat, just south of the Delta. The natural point of entry for Canaanites bringing flocks into Egypt was through the Wadi Tumilat.12 But an Egyptian pharaoh of the XVIIIth Dynasty (c. 1575–1318 B.C.E. on the high chronology)—after the Hyksos expulsion—would have been 350 miles away, in Thebes. How, then, did Moses, or, for that matter, Joseph, enjoy almost daily contact with the pharaoh?

In one source, Joseph instructs his brothers that they will settle in Goshen, so as to be close to him.13 The implication is that Joseph, the viceroy, resides near Goshen, in the eastern Delta. In the continuation,14 Joseph is reconciled to his brothers, “And the sound was heard in the pharaoh’s house” (Genesis 45:2). In other words, the pharaonic residence is close to Joseph’s, in the Delta. There are several other texts with the same implication.15 This can only be the case during the period of Hyksos rule in Egypt (c. 1800–1550 B.C.E.). The biblical tradition thus identifies Israel’s descent into Egypt with the Hyksos.

The Hyksos capital of Egypt has now been located—at Tell ed-Dab‘a in the eastern Delta, just north of Goshen. Semitic settlement there started by the mid-18th century at the latest.16 Assume that Joseph worked for the Hyksos: J’s idea of a 400-year sojourn places the Exodus under the Ramessides (13th century B.C.E.).

It was just in that era that Ramesses II relocated the capital from Thebes back to Tell ed-Dab‘a. The Ramessides reconstructed the Hyksos capital at Avaris—and called it Ramses; they were conscious of the Hyksos connections.

This same consciousness seems to underlie the biblical accounts, which locate the Israelites in Goshen in the Hyksos and the Ramesside periods. Settlement in Tell ed-Dab‘a persisted into the 11th century B.C.E.17 So Egyptian memories probably affected Israelite tradition. The author of the J source, after all, was no hillbilly: He was a literate adjutant of the court in Jerusalem, with the historical knowledge of a member of the elite. He simply located the Joseph story in a particular historical milieu, rather than in a vacuum. One of the kings of the XXIst Egyptian Dynasty (c. 1075–948 B.C.E.), possibly Solomon’s father-in-law (1 Kings 3:1, 9:16), transferred the capital from Ramses to Tanis. The transfer brought innumerable Ramesside and Hyksos monuments to Tanis.18 So traditions of Ramesside and Hyksos activity just north of Goshen, at Tell ed-Dab‘a, survived into the period when the Israelite court developed formalized relations with Egypt.

The mediation of these Egyptian memories to Israel either fostered a tradition that Israel’s ancestors ruled in the Delta region, or attached itself to such a tradition. At the same time, the presence of the Hyksos monuments at Tanis misled Israelite tradition into the conviction that Tanis, founded in the 11th century, was a Middle Bronze II (1800–1550 B.C.E.) site—hence the claim, in J, that Hebron—a Middle Bronze fortress—was founded seven years before Tanis, and later references to an Exodus setting out from “the plain of Tanis” (Numbers 13:22; on the plain of Tanis, see Psalm 78). Significantly, one of the monuments moved to Tanis was a stele of Ramesses II celebrating the inauguration of the cult of the Hyksos god Seth 400 years earlier.19 The idea of a four-century span between the Hyksos (and Joseph) and the pharaoh who built the city Ramses using Israelite labor must be traced, directly or indirectly, to that monument.

Overall, the Joseph story is a reinterpretation of the Hyksos period from an Israelite perspective. Admitting a relationship between Israel and the Hyksos, it affirms that the episode was part of a divine plan to preserve both the Asiatics and the Egyptians. The framework of the Joseph story, then, is plainly apologetic: It offers up the perspective of the despised “Asiatics” against centuries of Egyptian opprobrium. The tradition’s date is uncertain, but its most probable time of origin is in the tenth century, under, or just after, Solomon.

So far, we can conclude that Israelite tradition associated the descent into Egypt with the Hyksos period of Middle Bronze IIB–C (c. 1800–1550 B.C.E.). This association is not limited to the texts about Joseph. Abraham, for example, is thought to have settled in Hebron—which the Israelites knew to be founded on a rich Middle Bronze site.

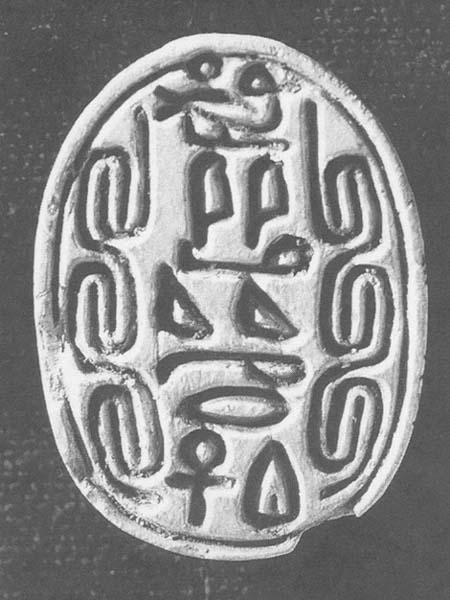

But are these connections to the Hyksos era purely literary and folkloristic? Two groups of data support the view that the Israelite nexus to the Hyksos has some historicity to it. The first is striking. The name “Jacob” appears on a number of scarabs as the name of at least one Hyksos king.20 All Israel claims descent from an ancestor named Jacob. The connection between the eponym, Jacob, and the forgotten name of the Hyksos king, in the context, is a tantalizing one.

Second, the names of the patriarchs in Genesis are almost uniformly of a type that most probably derives from the Middle Bronze Age, the Hyksos era. This is true of Isaac, Ishmael, Israel, Joseph and especially Jacob. Names of this type are relatively rare after the Middle Bronze, yet they appear in a high concentration in Israelite ancestral lore. Our inference should be that the ancestral lore has its roots in—that is, the names of the patriarchs derive from—the Middle Bronze Age, the period of the Hyksos.21 All the indications are that Israelite lore has in fact picked up on a stream of tradition the headwaters of which stem from that time.

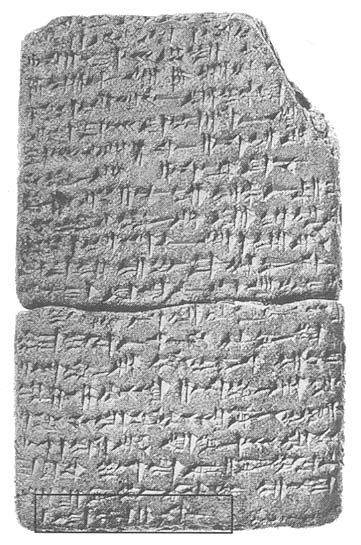

Now, what implications does this have for the event of the Exodus? The Bible places this event overtly under Merneptah (c. 1237–1227 B.C.E.), and the oppression under Ramesses II (c. 1304–1238). And there are convincing details: Texts of Ramesses II even refer to construction by captive ‘Apiru,22 an Egyptian term for a type of Semite sometimes encountered in small numbers on military campaigns. This term is probably related to the later Israelite word, “Hebrew” (‘ivri), used in the Bible to describe Israelite ethnicity to foreigners, and used frequently in the Book of Exodus. But the Egyptian term, “‘Apiru,” lost its currency by the tenth century. Though the Israelite ethnicon “Hebrew” survived, the juxtaposition of the two similar words may reflect the origins of the Egyptian term in the second millennium B.C.E.

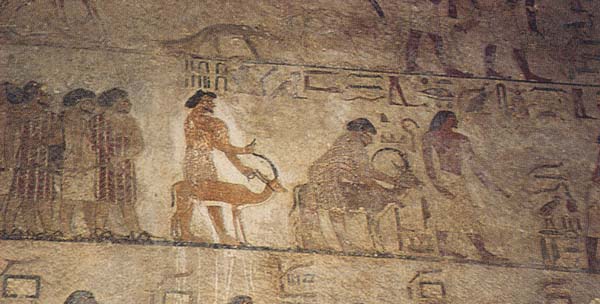

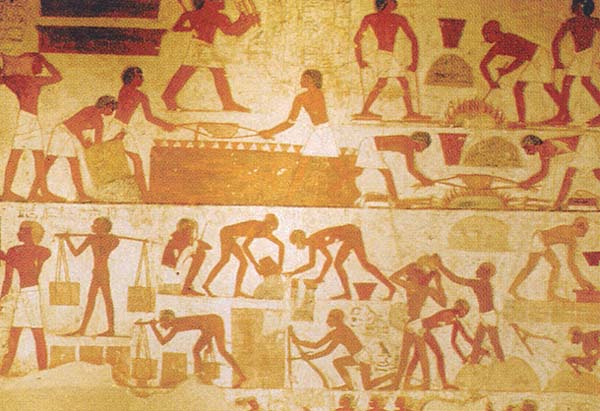

The brickmaking, too, described as part of the oppression, reflects close knowledge of conditions in Egypt. A 15th-century tomb painting depicts Canaanite and Nubian captives making bricks at Thebes. One text even complains about a dearth of straw for brickmaking—a situation encountered by Israel in Egypt.23 In Canaan, by contrast, straw was not typically an ingredient of mudbrick. Almost every detail in the tradition mirrors conditions under the XIXth Dynasty.24 Especially, the idea of a sudden rise in forced labor around the time of Ramesses II is entirely consonant with historical reality.25

To reoccupy Avaris/Per-Ramses, Ramesses II constructed a dominating palace, lavish temples and ambitious waterworks. He decorated his new capital with statuary and other monuments on a grand scale, almost without end. And, of course, he imported to the new capital the infrastructure to support both the ongoing construction and the government of Egypt.

At the same time, a significant proportion of the population of the Delta, drafted into public construction, was Semitic. Asiatic captives were typically employed in temple construction and other state projects under the XVIIIth Dynasty. But typically, this was in the south.26 It was the Delta, and especially the eastern Delta, that was an Asiatic cultural preserve.27 Its potential for labor was first tapped by Ramesses II. Ramesses II built huge public works on a truly massive scale all over Egypt, stamping his name across the landscape from the Delta to Abu Simbel. He made extensive use of forced labor, and no doubt of Semitic slaves, in these enterprises.28

However long the Israelites stayed in Egypt, then, the biblical presentation identifies Exodus with the end of the Late Bronze Age. Ramesses II is the pharaoh of the oppression, in the 13th century B.C.E. The city, (Per-)Ramses, was constructed in the 13th century: Pithom was also occupied at about this time, though its location remains a matter of some controversy.29 The scale of the Israelite enslavement, too, best matches the time of Ramesses II, when a strong and martial Egypt flourished, and monumental construction in the grand style reached its apogee based in part on exactions in Asia. In fact, if Ramesses II’s 400-year stele has inspired the biblical tradition of a 400-year sojourn in Egypt, a conviction that Ramesses II was the pharaoh of the oppression has actually shaped the development of Israel’s traditions: The Semites subjected to forced labor in the Delta identified themselves with the traditions of their Hyksos predecessors, against the Egyptian pharaoh; thus Israel came to identify itself with the Hyksos. The nature of the biblical tradition assumes a very reasonable cast if one assumes that behind it is an experience of forced labor in the late XVIIIth or early XIXth Dynasty.

Further, the list of peoples Israel allegedly encountered when en route from Egypt to Canaan speaks strongly for an exodus in the same era: Midian, Amalek, Edom, Moab and Ammon (Numbers 13, 14, 20–24). Moab first appears as a nation, organized as such, in the time of Ramesses II. The Edomites first appear as such under Merneptah, the son of Ramesses II, probably in southern Transjordan. Midian and Amalek occupied territory in the southern reaches of Canaan or in the Hejaz in Iron I, just after Merneptah’s time, but are unknown either before or after.30

The oldest Israelite literature about the Exodus from Egypt and the conquest of Canaan, the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15, describes Israel’s entry into Canaan in the following terms:

“The peoples heard, they trembled:

Writhing seized the inhabitants of Philistia;

Then, the chieftains of Edom were discomfited;

The chiefs of Moab—terror seized them.

All the inhabitants of Canaan melted away.”

Exodus 15:14–1531

The text places the Edomites and the Moabites in southern Transjordan. It also locates the Philistines on the western side of the Jordan, no doubt on the southern Canaanite coast (cf. “the way of the Philistines” in Exodus 13:17 [E]). Yet the Philistines did not settle in Canaan until the early 12th century. The Philistines first appear in reliefs at the Egyptian temple at Medinet Habu, outside Luxor. Here, Ramesses III claims to have repulsed them, from Egyptian Asia, in his eighth year (c. 1192 B.C.E.). Further, no Philistine settlement has been archaeologically identified in Israel before about 1200 B.C.E. Though Exodus 15 no doubt retrojects later conditions back to the time of Israel’s entry into Canaan, it reflects upon that development from no later than about 1100.

To date Israel’s entry into Canaan much earlier than the late 13th century raises this question: Why does Israelite tradition32—even in its earliest stages—have no recollection whatever of the Philistines arrival in Canaan long after Israel was ensconced there (cf. Amos 9:7)? This problem is attenuated if Israel’s arrival and that of the Philistines were virtually contemporary; it took time for the early Israelite settlement in the central hill country to spread to the regions bordering the Philistine coast (in fact, areas of Judah abutting Philistia were probably not settled until the 11th century).

This brings us to the crux of the matter, which is the relationship of the Exodus to the conquest. Bill Dever has devoted an entire talk to that subject, while I must restrict the articulation of my own view to a thumbnail sketch in this context. Still, in the 13th century, as just noted, a series of peoples emerge along the King’s Highwayl in Transjordan. Edom and Moab are mentioned in Egyptian documents. So are the Shasu, or pastoralists. The Bible recollects the existence of a Midianite league, and of Amalek, at about this time.m The people of Ammon, too, must have been in formation. Not very long afterward, Aramean kingdoms begin to arise in Syria, and Arameans are attested in northern Syria at the same time (with antecedents stretching back to the reign of Shalmaneser I [1274–1245 B.C.E.]). To these peoples—the Ammonites, the Moabites and especially the Arameans and the Edomites—the Israelites felt a close kinship. And the first Israelite settlements in the hills of Canaan probably stem from the latter part of the 13th century, too. These share their material culture with that of the Transjordanian populations, including not just pottery traditions and family organization, but also glyptic and naming traditions.33

The inference I draw is that a new population spread down from Syria along the King’s Highway over the course of the 13th century. This is the population the Bible identifies as Hebrew, an ethnicon, it will be recalled, that is used in the Bible only when foreigners are referring to Israelites. At least at the end of the Iron Age, the Bible portrays the Hebrews as the rightful successors of an indigenous population of Canaanites, Amorites or Rephaim.34

What could have impelled the new population to settle among the non-Hebrews in Transjordanian and Cisjordanian Canaan? The 13th century was a period of extreme turmoil in northern Syria and the Balih basin—the plain of Aram in south-central Turkey and northern Syria—to which Israelite folklore traces Israel’s roots.n In that century, Assyria gradually dismantled the indigenous Mitannian states and turned them into provinces. A considerable element of West Semitic speakers lived in the region north of the Euphrates along the Balih and Habur rivers. Some of them were pastoralists or dimorphic agrarianso in background, associated with hill territory and later referred to as Arameans.35 No doubt many converted their assets into livestock and migrated away from heavy taxation.

Some of the migrants found their way not just into southern Syria and Transjordan, but into the central hills of Cisjordan.36 Merneptah mentions this group in the celebrated Israel Stele.p Some of the evidence from the material culture suggests that the early Israelites enjoyed some familiarity with Canaanite culture.37 Still, most of the evidence linking the collared-rim jar, for example, to Canaanite towns, is susceptible to explanation on the basis of trade. Continuity in the pottery tradition between the Hebrew elements—including those in Transjordan—is susceptible to the same explanation if we adopt a model of gradual homesteading from Syria rather than of unified invasion. From differences in social organization—and its architectural articulations, from differences in household economy and from differences in economic strategies, I would conclude that Israelites, and their Transjordanian counterparts in Ammon, Moab and Edom, and farther north in Aram, were not indigenous to Canaan, and that their background lay in a combination of agriculture and husbandry, in many cases in a mountainous environment.

But it is inconceivable that all these new elements, who shared a common culture, should have participated in an Exodus from Egypt. The Arameans, Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites, at any rate, are not understood by the Israelites to have shared the Exodus experience: This indicates that they had no such national myth. And this, in turn, leaves us with the question whether earliest Israel in Canaan was itself the product of the Exodus, or whether, like the Jamestown colony in the United States, it was the beneficiary of a national myth formed from a subsequent experience.

Specifically, to understand the relationship of the Exodus to the conquest, we must ask, just what was the nature of the Exodus? As we have seen, much of the Exodus story is typologically true. That is, the narratives do not allow us to ascertain exactly to which people these events occurred, do not permit us even to claim that all the events occurred to a single group, but the details conform to the Canaanite experience of Late Bronze Egypt. There were Semites there, there was forced labor, there was brickmaking, there was intense building activity under Ramesses II, including of the city of Ramses. The list could easily be extended—Moses’ name is clearly Egyptian,q the story of Moses growing up in the court mirrors the practice of Egyptian kings raising the children of their Semitic vassals as hostages in the court. But it is most unlikely that a group of some three million people—or even 80,000, which is Manetho’s figure—left Egypt down the Wadi Tumilat in the reign of Ramesses or Merneptah. It is completely unthinkable that any group of any related size went rattling around in the Sinai Peninsula or the Negev for any length of time thereafter.

Last year, at the Wild Animal Park in Escondido, California, my younger daughter got her first glimpse of a unicorn. She saw it unmistakably, until the oryx she was looking at turned its head, revealing that, in fact, it had two horns. And in that moment, she learned that the difference between the mundane and the magical is a matter of perspective. That is probably the case with the Exodus.

What if it is the case that the very Exodus is itself typologically true? We have reports of runaway slaves escaping down the Wadi Tumilat. An official pursuing two runaway slaves in the late 13th century arrived a day after leaving the capital, Ramses, at “the enclosure-wall of Tjeku”—the station at the end of the Wadi Tumilat in Exodus; the two slaves then continued by a southern route into the eastern desert.38 The enclosure wall of Tjeku reflects Egyptian interest in controlling border traffic there—incoming and outgoing. Escapees from Egypt evidently might avail themselves of this route.

What is historically imaginable is repeated incidents of this stripe. We might even envision an instance in which a small group of pastoralists, tending sheep in the Wadi Tumilat, migrated out of Egypt, legally or illegally, in order to evade corvée. Such pastoralists, with no tradition of state labor, would regard Egyptian forms of taxation as nothing less than slavery. Yet, after a sufficient time in Egypt, they would also have assimilated some of the history of the Delta—and may even have identified themselves with the viceroy of a Hyksos king named Jacob. Of their own illustrious ancestry they had no doubt.

Escaping into the desert, too, was a sign that they had been touched by a god, and it is no coincidence that somewhere in the regions through which they migrated there was a “land of the Shasu (or, pastoralists) of YHWH,” attested in Egyptian texts of the 14th or 13th century.39 Nor, for that matter, is it in any way coincidental that it is from the same regions—Seir, the field of Edom—that Israelite liturgists of the Iron I period thought YHWH had come to conquer Canaan (Judges 5:4; Exodus 15:15; Deuteronomy 33:2–3, 29; Psalm 68:8–9, 18; later, Habakkuk 3:3 and 1 Kings 19). The very modest beginnings of a cult of YHWH associated with an exodus from Egypt can thus be divined in some incident, or series of incidents, that would be invisible to us archaeologically and historically—as the Exodus is.

So far we have a cult located somewhere in the southern steppe of Canaan and related to an exodus from Egypt. Were this the end of the development, it is safe to say that the Exodus would have left no imprint whatever on what the poet calls “the sands of time.” But it was not the end. For, somehow, the Exodus myth, and the community responsible for preserving it—and here, we should think in terms of a number of years, not of decades—came into contact with elements that were homesteading down the King’s Highway in Transjordan.

The mechanics of this step are impossible to stipulate, and here we are essentially doomed to remain forever in the dark. What we know is that the group responsible for introducing the Exodus story into the culture of Cisjordanian immigrants from Syria (whom we may call the Israelites) found a compatible culture in these immigrants, a culture that was receptive to the notion that the Israelites were immigrants in the land, whose property had been converted into livestock in the 13th and 12th centuries. The affinity was in no way coincidental: The Israelites (the migrants from Syria and those with whom they established connubium in the central hills) felt this affinity for Edomites in general40 (and for the nomadic Kenites41), and their folklore identified Esau, the ancestor of Edom, as the full brother of Jacob/Israel (Genesis 25:21–34; Deuteronomy 23:8; Hosea 12:4; Jeremiah 9:3; Amos 1:11).

The Exodus group found something else in the Israelites. Inside Cisjordan, the Israelites were the group most proximate to the centers of Egyptian control of Canaan. Of the “Hebrews”—Aramean, Ammonite, Moabite, Edomite, Arabian—they were most extensively exposed to sales of children into Egypt during times of famine, to Egyptian imposts, to Egyptian arms parading through the inland valleys and coastal roads of Cisjordan. Small wonder that they were also the most receptive to a cult myth conditioned on the assumption of escaping bondage to the Egyptians. It is impossible to say, now, whether the drowning of an Egyptian army in the Reed [Red] Sea celebrated in Exodus 15 occurred during the escape of the Exodus group from Egypt. The motif may be drawn from the drowning of a Canaanite army in the Jezreel Valley, related in Judges 5, or it may reflect some other event in which Israelites were implicated. In either case, the idea of defeating or escaping Egyptian arms is central.

The other factor in the development of the Exodus story is more central. For, in its Israelite incarnation, the Exodus story is also a promise of the land. Like the Mayflower Compact, it legitimated the ownership of the land, and, as in the case of the Pilgrims, the Israelites ratified the legitimation by eating the totem of the land, in their case a lamb rather than a turkey. The Exodus, without the conquest, would never have survived as a story.

From all this, it should be clear that we cannot know the precise relationship of the Exodus to the Israelite settlement in Canaan. What we do know is that the Exodus was certainly central to the ideology of the Israelites in Canaan already in Iron I. The victory at the sea in Exodus 15, 42 the tradition that YHWH marched forth from Edom to conquer Canaan,43 the Egyptian reference to the land of the Shasu of YHWH44 all point to the same conclusion. Sometime, relatively early in Iron I, Israel began to subscribe to a national myth of escape from Egypt, mediated by a god residing in the south (and outside Canaan), with the purpose of establishing a nation in Canaan. That national myth—justifying the Israelite land claims in Canaan—became a call to arms, a doctrine of Manifest Destiny, for a people newly arrived from the north and east.

The advent of Yahwism was a call to xenophobia against the lowland Canaanites, who are identified as the oppressor—a cultural stereotype that appears time and again in the earliest Israelite literature (Judges 5; Exodus 15, etc.). This xenophobia reflects antagonism on an ethnic level toward anyone whose ancestors had not participated in the Exodus. That is, the xenophobia of these texts is directed toward non-Israelites, inhabitants of the lowlands, Canaanites.

This, too, is the natural function of a national myth: such myths exclude others—as circumcision and as dietary restrictions do. The key thing to understand, however, is that in setting up a cult focused on liberation from slavery and on national enfranchisement in a land, ancient Israel was erecting a paradigm—not just excluding Canaanites—for the basic conditions under which an ethnic community could enjoy a sense both of separateness and of independence.

Questions & Answers

Question: There was a large volcanic eruption, in Thera, I believe, which caused huge tidal waves over the Delta. Apparently one could observe the fire over the entire Mediterranean area. Could you explain how this fits in with the myth that you mentioned?

Baruch Halpern: There have been a number of theories about the Exodus predicated on the assumption that the events as they’re described in the Book of Exodus occurred at the time of the Exodus. We don’t have an exact date for the eruption of Thera. The latest revisionist hypothesis is 1620 B.C.E. or thereabouts. I’ve seen dates down into the 15th century B.C.E. People say that if the plume of the volcanic eruption at Thera rose 30 miles into the air, you would have been able to see it from the Egyptian Delta. This then becomes the pillar of fire and cloud of smoke that the Israelites followed—not exactly the right direction, but they followed it anyway. (Laughter.) Two things come out of this. It used to be that we associated the explosion of Thera with the decline or the complete eradication of Minoan culture. It is often connected with the myth of Atlantis. As the story was retold, over time Thera became the island that sank, rather than the island that exploded. I suspect that the Thera story is actually the origin of the Sodom and Gomorrah story in Israel. Basically the Atlantis myth and the Sodom and Gomorrah story are the same story, just set in different environments.

Is Thera the pillar of cloud in the Exodus story? Quite possibly. Can we tie the Exodus chronologically to the Thera explosion? No, there’s no chance that we can do that.

Q: When did the word “Transjordan” emerge as a geographical term? If Merneptah had gone 50 or 80 miles east and wanted to brag about the conquest of that land, would he have referred to it as Transjordan? Isn’t “trans-” a Roman prefix?

Halpern: It’s a good question. What you’re saying is that I should not take the Merneptah Stele to imply that the Israelites are in Cisjordan. Is that correct?

Q: No, no my question is, when did the word “Transjordan” emerge as a geographical term?

Halpern: Not as a concept, just as a geographical term?

Q: Just as a geographical term.

Halpern: Well you do get words in Hebrew like ‘Ever ha-Yarden already in the biblical period, “across the Jordan,” which is what Transjordan means—and which is where the British stole it from, by the way.

Q: I’d like to endorse the use of names as an indicator of the origin of these traditions (which is also very helpful in other fields like British history). I think you make a very good case for the patriarchal period coinciding with Middle Bronze and with the Hyksos. But when you apply this kind of thinking to the actual Exodus, you get a very different kind of answer. You said the name “Moses” is an Egyptian name. In fact, it’s a made-up name. It’s a made-up Egyptian name meaning “son of” without being son of anything. This may be an alarm bell that here we have a story which is made up in much the same way as that of Romulus, which is also definitely a made-up name. This corresponds with what is generally agreed on in early Roman history as being almost entirely fictitious. So one should not place the actual Exodus story on this kind of evidence. One should place it on a very different basis from the fairly solid picture of the earlier sojourn in Egypt coinciding with the time of the Hyksos.

Halpern: There is something behind the Israelite tradition. The basic problem we all run up against—and this is true of the peasant revolt school or the conquest theory, and even the so-called archaeological approach to the conquest—the problem is that you wind up with Israel with an Exodus tradition, a tradition of having been in bondage in Egypt.

Q: What about Americans having British ancestors or European ancestors. Is it an ancestor myth?

Halpern: There’s got to be something behind it. It doesn’t have to be what it says it is, and it certainly wasn’t all-encompassing.

Q: But there is something behind it?

Halpern: Exactly. As to Moses’ name, by the way, we have names like “Bonnie,” not Bonnie and Clyde, but just Bonnie, which we call hypocoristic, which is a fancy word for nickname. “Bonnie” is a short form of “So and so has given birth” or “So and so has created a child.” It’s exactly the same as Moses—only the god’s name has been clipped off and a nickname has been made out of it. For example, if you took the name “Johnson” and just called the person “Son” that would be the equivalent of the name Moses.

Q: I found some of what you said confusing. I’ll try to clarify what I mean. Are you saying that the story of the Exodus was written years after it occurred by a group of people who tried to create a mythological, for lack of a better word, framework for explaining why Jews do certain things, such as circumcision and not eating pork, and for saying they [the Jews] are connected to the Exodus, to the Canaanite land: This is how we got here and this is how and why we are where we are?

Halpern: Let me clarify.

Q: And how many years were there between when the events occurred and when they were written?

Halpern: Number one, the earliest date for the writing down of any of this material would be the tenth century B.C.E. I think that’s an early date. I think that’s early by a century or more for the J source. And I think that the other sources that speak to this issue—the old poetry in Exodus 15 and Judges 5 and Deuteronomy 33—are probably Iron I (1200–1000 B.C.E.). Regardless of which model you use to reconstruct the rise of Israel, there is a considerable period of time passing between the events you reconstruct and the writing down of these accounts. When the accounts were reduced to writing, they were fixed—more or less. Although new accounts kept being generated, and they differ from the old accounts. What this reflects is the process of retelling. Now you asked me whether a bunch of people got together and concocted this story. I don’t think that’s exactly what happened.

Q: I didn’t say concocted the story; I said wrote the story down.

Halpern: O.K. So are you satisfied with that?

Q: No. My question is—Are you saying that the Exodus story in the Bible is a story that was written down hundreds of years after the event to give identity, or a natural myth, explaining two things: (1) why Jews did certain cultural things like circumcision and dietary laws and (2) how they came in possession of this land.

Halpern: What I’m saying is that the Passover, which became the celebration of the Exodus, had already become freighted with questions of that variety. And the Exodus myth developed in the context of the Paschal celebration into the form in which we have it now.

Q: Is there any connection between the development of the Israelite God Yahweh, the one god, and Akhenaten’s institution of the one sun-god?

Halpern: Not in my view. We have another speaker, Kyle McCarter, who may choose to address that question more specifically.

Q: I have read somewhere that there was recorded in Egyptian history an Exodus at some time.

Halpern: We have fragments of Egyptian history by a man named Manetho who was an Egyptian priest, writing in Greek [in the third century B.C.E.]. These fragments are preserved in a number of classical sources, such as Josephus, Africanus and Eusebius. But Manetho seems to be relying secondhand on the biblical story in order to reconstruct the Exodus and to tell it in a way that is abusive of, and hostile to, the Israelites. So I don’t regard that as an independent witness or as reliable testimony.

If you think the issue of the Israelite settlement is tough, it’s nothing compared to the Exodus. Now the Exodus, that’s a real tough one. We are very fortunate today to have with us to discuss the Exodus, Baruch Halpern. Baruch Halpern is a major younger scholar. He is not yet 40 years old. He has been at York University in Canada, but has just accepted a professorship at Penn State University in Pennsylvania, where he will form a whole new department of religious studies. All of today’s speakers, except myself have their Ph.D.’s from Harvard. Maybe that’s not so good, we are bringing you a Harvard perspective. Baruch graduated summa cum laude and his Ph.D. dissertation was accepted with highest honors. If I were to read Baruch’s curriculum vitae we would be here all day. He is the author of several important scholarly books, one called The Constitution of the Monarchy in Israel, another entitled The Emergence of Israel in Canaan and still another called The First Historians. He is widely known as a brilliant and insightful speaker, as well as a writer. I’m sure you’ll enjoy him and learn from him. It’s a pleasure to introduce my friend Baruch Halpern.—H.S.

Thank you very much. Hershel began his talk with the comment that you could accept whatever he said unequivocally. I wish I could say the same thing about his introduction. (Laughter.)