The Origins of Israelite Religion

What motivated the changes that previous speakers have noted in the archaeological record when the Israelites emerged in the central hill countr of Canaan? What were the reasons behind the emergence? Did religion play a part? Bill Dever candidly admitted that archaeology couldn’t provide an answer to this question. So it’s quite a challenge for our last speaker to deal with the question of religion—the origin of the Israelite religion and how religion affected this emerging people, Israel. I don’t think we could have gotten anyone better in the entire world to explore this difficult aspect of our subject today than Kyle McCarter. Kyle also received his Ph.D. from Harvard. He is one of the broadest, most eclectic biblical scholars I know. He can deal with so many different aspects of the discipline—from archaeology to ancient languages to inscriptions to the biblical text itself. He is the author of the two-volume commentary on Samuel in the Anchor Bible series. He is a past president of the American Schools of Oriental Research. He presently holds the chair—I wonder how he feels when he wakes up in the morning knowing the title of his chair—the William Foxwell Albright chair at the Johns Hopkins University. Albright was of course the doyen of biblical archaeologists of an earlier generation. Kyle is the William Foxwell Albright Professor of Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. It’s a pleasure to introduce to you my friend Kyle McCarter.—H.S.

It’s a special treat to share the podium with colleagues of the caliber that Hershel has gathered together for us. Bill Dever speaks with as much authority as anyone in the world on the subject of the archaeology of the region that we are interested in and Baruch Halpern has written the most important book to date on our subject. So it’s an honor to be here with them and to hear what they’ve said. It has created a problem for me, though, because they’ve already said everything there is to say. (Laughter.) You’ve heard it all now, and I’ve decided to talk about the legend of Robin Hood. (Laughter.) Not really.

Hershel, I want to comment on an interesting fact, I believe I see a new consensus emerging. I think we’ve gotten far enough along on this subject where we can begin to say that there is a new commonality emerging among scholars about what occurred at the beginning of the Iron Age in Palestine Israel. I say this because I find myself so much in agreement with what Bill and Baruch have said.

And I sense the collapse of the paradigm that we set for ourselves in the past—a paradigm that Hershel articulated to you. We posited three models for the origin of the Israelite state—military conquest, peaceful settlement and social revolution—and asked which of these three was true.

That paradigm has become obsolete, and we are at the point where we don’t have to talk about three possible models anymore. We are developing a new model.

I think the basis of the new model is Baruch Halpern’s book on The Emergence of Israel in Canaan.1 Working from the arguments in that book and other similar scholarship, we have begun to develop a new consensus. If you look back on the things that the three of us have said today, I expect you’ll see more common features than disagreements. It’s not because we all went to Harvard (laughter); the subject is too new for us to have been indoctrinated into any kind of conformity. There is no sense in which Bill, Baruch and I are part of a group of investigators who are trying to persuade our colleagues of a new way of looking at the complex phenomenon of the beginning of the Iron Age in Palestine.

At this point, however, I do want to introduce a note of disagreement, and I’ll use it to introduce my remarks. I don’t claim to be an archaeologist. I work with historical and literary materials. So let me begin by offering a literary objection to a common assertion made by archaeologists about the Book of Judges: the assertion that the account of the conquest of Canaan in Judges 1 is a more authentic picture of what went on in Iron I than is the larger account in the Book of Joshua. Judges 1 gives what seems to be a much more realistic, modest and measured account of the conquest.a In contrast to the swift and thorough capture of the land described in Joshua, Judges 1 says that most tribes didn’t succeed fully in driving out the people in their assigned territories, though maybe one or two tribes did. Therefore, we are told, Judges 1 may be an earlier, less ideologically based and historically more reliable account than that of Joshua.

But let me mention a very interesting fact. If you examine one of the most important witnesses to the ancient text of the Hebrew Bible, namely the Septuagint, the early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, you will find that in all likelihood in its earliest form it lacked Judges 1 altogether. When you come to the end of the Book of Joshua, you find yourself reading the story of Ehud, the first of the great heroes of the Book of Judges. What that almost certainly means is that the Hebrew text from which the translator of the earliest Greek version of Joshua-Judges was working didn’t have Judges 1 in it.

Now, this text-critical fact is open to more than one interpretation. On the surface, all it means is that in antiquity there was a text of Judges that didn’t have chapter 1 in it, and that chapter 1 was added to that text later. It was inserted into the Greek by a later Greek translator. What are the possible interpretations of this shorter version of Judges? It’s possible that someone removed Judges 1 from a text of Joshua-Judges that included it. But that’s not very likely. Ancient scribes were inclined to be inclusive. They respected, even revered the text they worked with. And so a basic principle that we work with as textual critics is that the scribes are not likely to have removed something. If you have two versions of a text—one longer and one shorter—it’s much more likely that the shorter text is earlier and the longer text is later, that something was added along the way. So it is very likely that there was a time when the Hebrew text of Joshua-Judges existed without this chapter that is so crucial to the archaeological discussion here. Or to put it differently, at some point this chapter existed as an independent document and was inserted in the Bible.

Even so, this fact could mean more than one thing. It could be that Judges 1 was a very ancient document that was added at a very late date to the biblical text. Alternatively, it could be that Judges 1 was simply a very late document. These possibilities have led me to ask myself the question how Judges 1 might be understood as a late document rather than a very early document? I had been taught the theory that you heard from Hershel and Bill that Judges 1 was probably a more authentic and reliable account of the conquest than Joshua and likely, therefore, to be quite ancient. But now I ask myself if there is a way of thinking of Judges 1 as a late composition.

If you read Judges 1 very carefully you will find an interesting thing. It doesn’t say in every case that the tribes were unable to drive out the local inhabitants from their allotted territories. It says that in most cases, but there are two exceptions who were able to drive out the local inhabitants. One is the case of the tribe of Judah and the other is the tribe of Benjamin. Now the effect of saying this is to suggest that the most consistently Israelite population, the least mixed population, is in the tribal territories of Judah and Benjamin. If you consider this suggestion within the context of the history of Israel, and if you look at post-Exilic history in particular, you’ll find a time when most of the land of Israel apart from Judah and Benjamin had been lost to the government in Jerusalem for an extended period of time. Moreover, the post-Exilic period is the time from which we have literature that touches on the reforms of Nehemiah (see Nehemiah 13), specifically, the attempt to purify the Israelite population, to reject foreign marriages and so on. Then if you ask if it would make sense in this period to compose a document that depicted the conquest the way Judges 1 does, you get a positive answer. By depicting the territories of Judah and Benjamin as those with the most uniform population of Israelites as opposed to foreigners, Judges 1 supports the agenda of Nehemiah’s reform and the contemporary suspicion concerning “the people of the land” with whom the Jewish repatriates from Babylon quarreled (see Ezra 4:4, etc.).

So Judges 1 fits pretty well into that post-Exilic period. It could have been composed at that time and inserted into the older text of Joshua-Judges. I suspect that’s the case, though I haven’t found enough evidence to convince myself that it’s certainly the case rather than what we’ve always thought. In any case, I hope the example raises the kind of issue that, as I’m sure my colleagues would agree, shows the peril we’re in when we’re doing biblical archaeology. When we’re dealing with a literary text employing literary-critical criteria, our results don’t correspond in a straightforward way with what we find, as Bill put, “on the ground.” It may be that Judges 1 corresponds better with what Bill finds on the ground, but that correspondence may be an accident. Text-critically there’s a lot of reason to think of Judges 1 as a document that’s at least half a millennium too late to be relevant to the discussion of the early Iron Age. Does that seem to you to illustrate the complexity of the issue we’re dealing with?

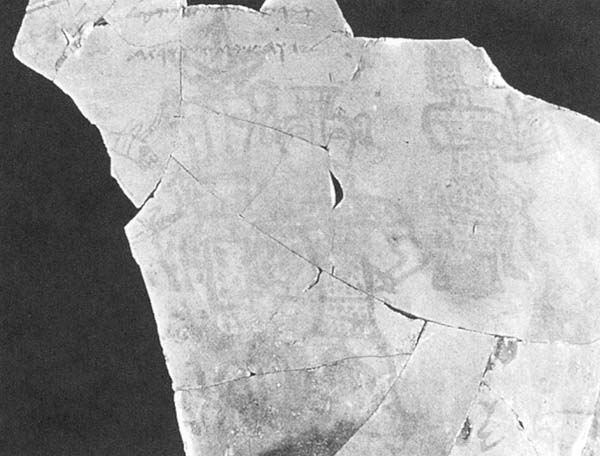

Hershel said to you that I work in all the various disciplines of our field. That was a very polite way of saying that I try to work as an amateur in the field. I play at archaeology and I play in the other areas. This variety gives me a perspective on the difficulty of comparing one of these issues to another. Let me paraphrase and partially quote a poem for you. It’s a poem that belongs in the corpus of archaic Hebrew poetry. This is the corpus that Baruch Halpern emphasized to you as having special importance in our reconstruction of Israelite history and prehistory. The earliest portion in the biblical text that we can determine is the so-called archaic poetry, but the archaic Hebrew poem I’m going to talk about is not biblical. It was found at a site in the northern Sinai called Kuntillet Ajrud.b It is written in ink on plaster, on the wall of a building. The script is Phoenician rather than Hebrew, but the language is Hebrew. The site dates to the beginning of the ninth century B.C.E., but the poem belongs to the corpus of archaic Hebrew poetry because of its content and its nature, not because of the archaeological date of the site. Poetry is to be dated on the basis of established typologies of poetic form just as pottery is dated on the basis of ceramic typologies. On the basis of what we know of archaic Hebrew poetry, I would estimate that this poem, though it survives only in a ninth-century text, is probably an Iron I composition (1200–1000 B.C.E.).

The poem is very fragmentary, so I can’t make it very elegant for you. It begins “When El shone forth … ,” using the divine name El, which in the Bible is one of the names of the God of Israel and, as Bill pointed out earlier, is also a common name in the Canaanite pantheon for the king of the gods. “When El shone forth. … ” The word I’m translating “shone forth” is a Hebrew verb that refers to the rising of the sun. Shining forth like sunrise is the image here. I don’t want to suggest to you as our colleague Mark Smith from Yale would that there’s solar imagery here, though I think Mark is certainly right that solar imagery is sometimes applied to the God of Israel in the Bible, and that scholars have given it too little attention.2 The point here, however, is that the image the verb is drawing on in describing the appearance of El is sunrise, and that the sun rises, obviously, in the east.

A few lines after “When El shone forth” we read, continuing the same idea, “When Baal [arose] on the day of battle. … ” The expression “on the day of battle” (b’yom hammilchamah) is strongly reminiscent of the biblical concept of “the day of Yahweh,” which refers to a special event that the prophets looked forward to, a time when the God of Israel would arise in battle and defeat his enemies (see, for example, Isaiah 2:12–21, 13:6–10; Jeremiah 46:10; and Ezekiel 13:5). The use of the divine epithet Baal here, in combination with the fact that the script is Phoenician, has led some people to suggest that this is a Phoenician text and that there was a mixed population at Kuntillet Ajrud. Everyone recognizes that there was an Israelite presence there but they say there must also have been Phoenicians. But I don’t really think so. I think that “Ba’al” here is simply an epithet meaning “lord.” That’s the common meaning of the Hebrew word ba’al, and there’s very strong reason for believing that in early Israel, specifically during the early monarchy, the title or epithet “Ba’al” was an acceptable title for Yahweh. It was rejected later because it had so many associations with rival gods; in fact, ba’al eventually became a standard way of designating rival gods. But I think that the expression in the Kuntillet Ajrud poem simply means “When the lord [arose] on the day of battle.”

In between the phrases “When El shone forth on the day of battle” and “When the lord [arose] on the day of battle” are verses describing the mountains melting in fear. The rest of the text is too fragmentary for reconstruction. (In one of my reconstructions there are six people riding on a single donkey [laughter]. I don’t know what that might mean. I once corresponded with Professor Frank Cross of Harvard about this text and sent him that reading. He replied by saying that he didn’t really have an opinion about the interpretation except that mine was almost certainly wrong. I agree. Six people riding on a donkey is a very uncomfortable reading. Especially for the donkey [laughter]. So I think that it’s best to say the text breaks off.)

Now why do I describe to you such a poorly preserved text? The reason is that it represents an addition to this important corpus of poems that we have from the Bible, the archaic poetry. As I mentioned, this poetry has been identified as especially ancient on the basis of studies of poetic form. The corpus includes poems like Exodus 15, Judges 5, Deuteronomy 33, Habakkuk 3 and Psalm 68 (

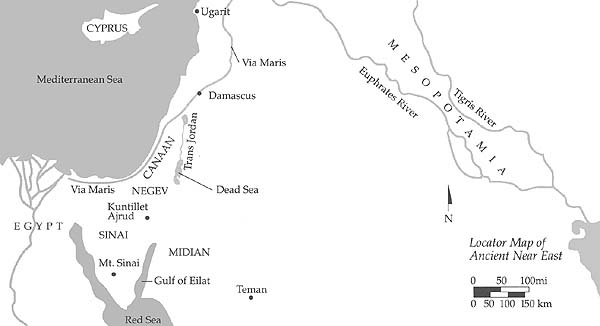

What do those poems have in common that might give us some information about the early worship of the God of Israel? What they say most consistently is that he is a warrior. He marches to battle against his enemies and on behalf of his people, and when he marches he comes from the southeast. He comes from Teman (the southland) (Habakkuk 3:3) or from Edom (Judges 5:4), the country southeast of Judah, or from Sinai. Thus there is a series of geographical locations associated with this poetry that places the God of Israel in the earliest time that we can trace him to the south and east of historical Israel and Judah, and more specifically just to the east of the Wadi Arabah. Based on this observation and others, some scholars long ago concluded that somehow the worship of Yahweh, the God of Israel, had its origin south and east of Israel and Judah in the region which today includes the northern part of Saudi Arabia, southern Jordan and Israel.

Let me add some other reasons for revisiting this old idea. Theophany is a term that refers to an appearance or manifestation of a divine being. Mt. Sinai is the principal place of the theophany of Yahweh. Interestingly, this is true not only in the current form of the biblical story, but also in the early form of the tradition. Yahweh is associated with Sinai not only in Exodus 19, a relatively late passage that describes the arrival of the Exodus party at the mountain, but also in the earliest poetry, as we have seen. The persistence of the Sinai tradition is remarkable, because there was a natural tendency to eliminate it. That is, there was an understandable tendency to transfer the mountain location of the theophany of Yahweh to some place within the Promised Land, and specifically to Jerusalem. And, in fact, in the royal theology that grew up after the establishment of the Davidic dynasty, Mt. Zion was the sacred mountain. According to the Zion tradition, the Solomonic Temple was Yahweh’s dwelling place forever (1 Kings 8:13). Why, then, didn’t Mt. Zion displace Sinai altogether? The only explanation I know is that the old Sinai tradition was so venerable and well known, that it was so persistent and authentic, that it couldn’t be suppressed.

Another indication that Yahwism originated south and east of Judah is the Midianite tradition. You remember that in the Exodus story Moses flees from Egypt into the wilderness and has his encounter with Yahweh. This momentous event takes place precisely in the region that we are talking about. The tradition was that the first encounter between Yahweh and the Israelites was in Midian, Midian being the name used in the Exodus story for this same region. This takes place in Exodus 2 and 3, where Moses marries the daughter of a man named Jethro. Jethro is a Midianite priest, and at one point (Exodus 18:11) Jethro says that Yahweh is the greatest of the gods. Exodus 6 shows that according to one part of the biblical tradition the God of Israel revealed his name Yahweh for the first time in Midian. In other words, even the Bible itself suggests that, in one sense, Yahwism originated south and east of Judah.

I want to back up into a discussion of the prehistory of Israel and Canaan, the subject that we’ve been talking about, because I don’t think these subjects can be separated from one another. I would describe the process that Israel went through when it established itself in Canaan as a process of ethnic self-identification. It involved Israel’s drawing boundary lines between itself and other peoples. This is why the question of where the increased Iron I population in the central hills came from is really a secondary issue in explaining Israelite origins. Wherever they came from—and I think their origin was diverse—they became a single people by drawing an ethnic boundary around themselves through the development of an elaborate genealogy.

An important part of this boundary drawing involved religion. The Israelites were those who worshiped Yahweh, the God of Israel. Similarly, the Ammonites were those who worshiped Milcom, the god of Ammon; the Moabites were those who worshiped Chemosh, the god of Moab; and the Edomites were those who worshiped Qaus, the god of Edom. Primary devotion to a chief national god was the characteristic pattern of the religions that developed in Iron Age Palestine. This suggests that Yahwism and Israel arose at the same time as a part of the same process. Let me explain

As we’ve seen, the setting of the prehistory of the Israelite community was the central hill country, which consists of highlands separated by a series of valleys. In the north is the Beth-Shean corridor that separates the hills of the Lower Galilee and Samaria via the Wadi Kishon and the Jezreel Valley. In the south is a series of valleys, including Aijalon, that separates the Samarian hills from those of Judah. It was in the upland region between these two valley systems that Israel emerged. As you’ve heard today, this region was very sparsely populated before 1200 B.C.E., and recent archaeological surveys have attempted to document the increase in population that began after 1200. One point that needs emphasis is that the boundaries of this region were dictated, I think, by Egyptian control of the major valleys and of the Via Maris or, as the Egyptians themselves called it, the Way of Horus—the road up the coastal plain. That road, which ran from Egypt across the northern Sinai, up the coastal plain of Palestine, through the Megiddo pass and onward to Damascus and points north, was a major route that the Egyptian empire needed to control for its own economic and political interests. This Egyptian control of the coastal plain and the major valleys had the effect of sealing in and isolating the central hill country. The small number of people who lived there lived in isolation from neighbors to the north, west and south.

At the end of the Late Bronze Age, events took place that led to the penetration of new people into the central hills. They settled in villages in the forests of the Ephraimite plateau in the east and north and in the saddle of Benjamin in the south. We’ve heard a lot today about where these people might have come from, and I find myself in general agreement with what Bill Dever told you. For a variety of reasons, life in the lowland cities was destabilized at this time, and there are a number of reasons for supposing that there was a substantial amount of movement out of those cities and into the central hills. If this is true, the movement was associated with a shift from an urban to a village lifestyle.c I suspect eventually we will learn that major fluctuations in weather were affecting this. When the weather becomes drier, it’s more difficult to maintain large urban areas, and it’s easier for people to live in villages. And there is some incidental evidence that in the last part of the Late Bronze Age the weather became increasingly and significantly drier in our region. The evidence is more than incidental for Mesopotamia, for which paleoclimatic studies have been done and published for the Late Bronze Age,3 and corresponding changes in weather patterns in Europe during this period are well documented.4 So it seems very likely that eventually we’ll find that one important factor that was forcing people into rural settings was simply the inability of cities to sustain themselves in a drier period.

Many other factors contributed to the change of settlement patterns in Iron Age I, and you have heard about some of them today. The dramatic increase in population in the hills no longer needs to be explained by positing an invasion. It’s true, of course, that new people were arriving in Palestine.d The Philistines were arriving and other Sea Peoples were settling on the coastal plain at this tune. But, at least in my opinion, their settlement was not so much the cause as one of the results of the change. We know that these Sea Peoples were in the eastern Mediterranean for some time before 1200. Much like the Vikings in northern Europe at a later time, they lived by raiding coastal villages, taking booty and sailing away. They had lived this way for centuries. Then circumstances changed, permitting them to settle down instead of plundering and running. The changed circumstances had weakened the large population areas to the point where they could no longer resist the attacks from the sea.

Egypt had become too weak to sustain an empire. The population in the large coastal cities and in the major cities of the valleys, such as Aijalon and Jezreel, began to decline. The cities began to collapse, and the nearby highlands began to fill up with new settlements and new villages. You’ve heard the word “Shasu” today, an Egyptian term for Asiatic nomads. Were there Shasu among the settlers in the hills? Yes, in all probability there were, though it’s very difficult for archaeology to confirm the arrival of the occasional nomad.e And in any case, the Shasu don’t seem to be the major element. To be sure, some of our colleagues in Germany still describe the population expansion in terms of Bedouin settling down and, as Bill pointed out, some Israeli scholars agree. But the old settlement theory, as expressed in classic form by the German scholar Albrecht Alt, has no more to recommend it today than the invasion or armed conquest theory, and the social revolution theoryf has failed because of a total lack of supporting evidence. Instead, we now see the emergence of Israel as a complex phenomenon involving, first, the arrival of new peoples in the central hills from a variety of sources, including especially the collapsing cities of the Egypto-Canaanite empire, and, second, the gradual process of ethnic self identification that generated an elaborate genealogy linking the highlanders to each other.

This brings us to an interesting and extremely important fact. There was something called Israel in Canaan before all this happened. When I was trained in this field, I was taught that Merneptah’s so-called Israel Stele, which you’ve heard about quite a bit today, was the key in dating the arrival of Israel in Canaan.g When the standard question of the conquest of Canaan was asked, the answer always invoked Merneptah’s campaign late in the 13th century as a decisive terminus ante quem. Because the stele mentions Israel, the conquest must have taken place earlier. In view of our wealth of new information, however, Merneptah’s stele now appears totally different in its significance, though no less important. Now that we know that the population of the central hills, which would become the heartland of Israel, burgeoned in the Iron I period after rather than before the date of Merneptah’s campaign, we have to revise our understanding of the stele’s significance completely. It shows us something quite different from what we thought before. It shows us that there was in Canaan something, some entity—some people who could be identified as Israel—before the changes that created what we usually think of as early Israel took place.

This point, then, is crucial. Somewhere in the sparsely populated hills of Late Bronze Age Canaan, there was a people called Israel. When newcomers settled in the hills in the subsequent period, at the beginning of the Iron Age, they allied themselves with this proto-Israelite group, and the eventual result was the formation of what we usually think of as early Israel, a group of tribes bound together by genealogical ties who would eventually evolve into a nation-state.

You may wonder what I mean by saying that new people arrived, affiliated with Israel and became Israelites. Israel was, after all, an ethnic group—a people united by kinship. So it might seem that someone either was or wasn’t an Israelite. We can understand how a non-Israelite might affiliate with Israel politically or religiously, but could someone affiliate ethnically? The answer is yes. Kinship is, of course, defined by biology and expressed by genealogy. But in many societies specific relationships within a genealogy may be artificial from a strictly biological point of view. That is, factors other than biological descent often come into play. In most kinship systems, affiliation by marriage or adoption constitutes kinship. In some systems, there are other non-biological ways in which kinship can be established. If you go to the social-scientific studies of ethnicity that have been done recently, you’ll find that there is a strong interest in this subject. Researchers have studied populations around the world in an attempt to determine how groups of people identify themselves as kin over against other groups. There is a special interest in kinship groups who live alongside other groups in a mixed population. The question is, how do ethnic groups assert and sustain their identity? In a variety of ways ethnic groups draw boundaries around themselves. They may do this with religion or languages or accents or codes of dress or diet or a combination of these and other things. But in one way or another they draw boundaries around themselves. And this boundary-marking is what creates ethnicity.

A process went on in the Iron I period where a large population who had not previously been Israelite identified themselves with a small group that had previously been Israelite by a process of ethnic boundary-marking. When you read the Bible, you find evidence of this. The biblical writings frequently and persistently assert that the Israelites are not Canaanites and that the Israelites should not marry Canaanites. There’s great emphasis in the Bible on family history and genealogy. All this comes out of a very long tradition of boundary-marking. It was that tradition that created Israel in the first place.

Interestingly enough, moreover, the boundary-marking created Israel not by total innovation but by identification with an existing people. Who were these proto-Israelites? Let me attempt to answer this question in the context of a hypothesis. In the Late Bronze Age, I suggest, there was a continuum of culture in the hinterlands of Palestine and Transjordan, the backwater region outside of the main lines (the coastal plain and major valleys) that were controlled by the Egyptian empire. This region extended in a crescent from Dothan and Shechem in the northern Samarian hills east into central Transjordan and south to the northeastern shores of the Gulf of Eilat. These boundaries, again, were dictated by Egyptian control of the lowlands. The hinterlands, sealed on the north by the Beth-Shean corridor and on the south by the valley of Aijalon and the Negev, were isolated from the influence of the Egypto-Canaanite culture of the lowlands. The customs and ideas that developed during the Late Bronze Age in this isolated region are not the Canaanite culture that we are familiar with from reading the Canaanite texts from Ugarit or from the reports of the Egyptians and Hittites of their experience with the peoples of lowland Palestine.

As Bill explained, the archaeological surveys of Iron I sites in the hill country have revealed a wide distribution of distinctive Iron I pottery types that extends beyond the hills of Samaria and Judah into central and southern Transjordan, the region that would eventually become Ammon, Moab and Edom. The uniformity of this pottery tradition, together with other indications, suggests a common cultural background that is most easily explained as a consequence of a continuity throughout the region in the Late Bronze Age. Now, what I am suggesting to you is that in that period, the Late Bronze Age, the earliest characteristic aspects of Israelite culture developed, most especially the worship of the God of Israel. This is the only period in which the central hills of Palestine, where Yahwism took root, and the region northeast of the Gulf of Eilat, where Yahwism originated, were connected in a cultural continuum. After the rise of the nation-states of Ammon, Moab and Edom early in the Iron Age this continuum was brought to an end. Thus if Yahwism came to Israel from Midian, as it almost certainly did, it had to arise in the Late Bronze Age and not in the Iron Age.

All this suggests that the Israel that existed at the time of the Merneptah Stele was an Israel that was already Yahwistic. Thus the population that began to flow into the area where these proto-Israelites lived in the Iron Age allied itself with the religion as well as with the people. The traditions they embraced were strong enough that once the nation-states of Israel and Judah were created, they already had Yahwism as a basic component of their culture. Later, in the Iron II period, when Israel began to worship Yahweh of Samaria, as he’s called in the Kuntillet Ajrud inscription, and Judah began to worship Yahweh-in-Zion, as he’s called in the Book of Psalms, neither of those national religions was strong enough to eradicate the memory of the proto-Israelite or pre-Israelite Yahwistic religion that, in a real sense, created the people and made possible the existence of the two countries.

Questions & Answers

Question: Reference is sometimes made to a consort of the God of Israel. Can you comment on that?

P. Kyle McCarter, Jr.: Yes, but it’s such a complicated question I can’t answer it in a sentence or two. The question has to do with the consort of the God of Israel. Is the God of Israel really a bachelor god or not? One of the things we learn from the Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions is that there was a tradition of Israelite piety (and probably Judahite piety as well, since both the southern and northern kingdoms are represented at the site) that included the worship of a goddess alongside Yahweh.h So the short answer is: Yes, some Israelites in some historical periods believed that Yahweh had a consort.

But we shouldn’t think of this Israelite goddess in quite the same way we think of the Canaanite goddesses of the Bronze Age pantheons. Yahwism, once it had arisen, had characteristics that differentiated it sharply from Bronze Age religion. Iron Age religion in Israel—and I think also in Ammon, Moab and Edom and probably in certain of the Aramean states—was not like Bronze Age religion. We know a lot about Bronze Age religion; we don’t know much about Iron Age religion from primary sources. We know it only filtered through biblical writers who after all were writing from a perspective of a fully developed monotheism, which came later. But as I would reconstruct it, the official religion practiced in the capital cities of Israel and Judah in the ninth century B.C.E. saw Yahweh in conjunction with a consort who was the personification of his cultically available presence.

What does that mean? If you go into a church or a synagogue or a temple, you say the presence of God is here. Now in certain periods in antiquity the cultic presence of a god worshiped in a given shrine is attributed substance. The technical term for the substantial form of an abstract concept such as cultic presence is “hypostasis.” Sometimes the hypostatized form of a deity’s cultic presence is personified. When it’s the presence of a male deity, the hypostasis is characteristically personified as a female deity. My interpretation of the question of the consort at Kuntillet Ajrudis that she was the personified form of the hypostatized presence of Yahweh. To put it differently: She was the available medium through whom you invoked him. And she was also thought of as his consort. And so, yes, we now know that the God of Israel in some circles was not regarded as a bachelor.

Of course, we should have known that already, because the biblical prophets, who didn’t approve of the arrangement, frequently use language that implies that the Israelites were worshiping a goddess, and the historical books of the Bible say explicitly that the kings of Israel and Judah worshiped the Asherah. There was a stream of religion that rejected the goddess, however, and that stream finally vindicated itself in the form of Yahwism that became Judaism, so that Judaism became a religion that permitted no plurality, even a male-female duality, in the deity. That’s why the idea of an Israelite goddess seems alien to us, whereas in the Iron Age it was a fixed feature of the religion—at least in certain circles.

Q: Just who are the Philistines, according to what we know now? Are they Mycenaean or Greeks or something else?

McCarter: They are one of the peoples who appear in the eastern Mediterranean at the end of the Late Bronze Age. They are first referred to by the name Philistine—Peleshet or Pereshet—in Egyptian sources, and are commonly mentioned in the documents of Ramesses III, who flourished in the second quarter of 12th century B.C.E. They settled down on the coastal plain of Canaan, south of the Carmel spur, which became known as the Philistine Plain. Later their name became one of the names for the whole country—Palestine. According to biblical tradition, the Philistines came originally from Crete—biblical Caphtor. In all probability, this tradition reflects historical reality. Scholars have found iconographic evidence and other reasons to connect the ancestors of the Philistines with Crete. One of the peoples mentioned in the Bible as close neighbors to the Philistines are the Cherethites, a group of whom became mercenaries in King David’s personal bodyguard, and a likely interpretation of the term Cherethites is that it derives from Crete.

Q: In light of your comments on the presence of God—the hypostasis—could you connect that with the findings in the Jewish temple that was found in the island of Elephantine in the Nile. I believe the shrine there was devoted to Yahweh and two goddesses.

McCarter: There are Aramaic documents from the Persian period that preserve correspondence between a Jewish community on an island in the Nile, called Elephantine Island, and Jerusalem. That is, we have correspondence between the main Jewish community and an Egyptian Jewish colony, in effect. These documents show that the Elephantine community had not only temples to Yahweh, whom they called Yaho, but also a number of other deities who seem to be Jewish and which have aspects of Yahweh in their names. A long time ago, Albright suggested that the other deities were aspects of Yahweh, rather than syncretistic deities from other religions. I subscribe to that idea. I think Albright was right about that. He had a clear perception of the complexity of reconstructing religious forms that we’re not familiar with. I think it’s too simplistic, as I’ve already said, to say there’s Canaanite religion, there’s monotheism and then there’s syncretism. There’s a whole set of religious ideas in between that we need to describe. The Elephantine documents provided our first clue. They are a primary source for interpreting the Kuntillet Ajrud material.

Q: Would you consider Psalm 29 in that early genre?

McCarter: Yes. Although I failed to mention it, I absolutely would include Psalm 29 in the corpus of archaic poetry.

Q: I have great trepidation in asking this because I’m afraid I’m going in the face of tremendous scholarship. But the conquest hypothesis seems to be pretty much defunct at this point. Yet, if you consider the Bible to be something that’s trying to establish the pedigree of the people and the title to the land, wouldn’t it have been to the advantage of the authors or the redactor to have said, “Yes, we arose from an indigenous population and hence have a pretty clear claim to the land,” rather than saying “we are intruders from the outside who have conquered it by the sword”?

McCarter: Since I was talking about religion, I really didn’t have a chance to say much about the conquest hypothesis, and I’m happy to have an opportunity to do so. I described the situation as I understood it: A new population came into a geographically isolated area and affiliated with an ethnic and religious community that was already there. As the highland population became increasingly numerous and the cities in the lowlands became increasingly vulnerable, there eventually and inevitably came a time of conflict. The people in the hinterlands conquered the lowland cities—not in one great campaign, but one after another over an extended period of time. We can date the process reasonably. We know, for example, that Beth-Shean held out as an Egypto-Canaanite city until at least the time of Ramesses VI (1141–1134 B.C.E.), whose name appears on a scarab found there. We know from the Bible that Jerusalem remained independent until the time of David. But eventually these cities fell to Israelite conquerors. What I would suggest is that it is the memory of the victories against these cities and their capture by the Israelites in streamlined form that created the tradition behind the Book of Joshua. I think the conquest in the Joshua story is not a historical document at all, but a religious confession having to do with the sacrality of the Promised Land. Nevertheless, I think it contains within it a tradition that goes back to historical battles and the actual conquest of lowland cities by Israelites. In short, I wouldn’t abandon the conquest model altogether, because I do think that the conquest stories include a recollection of actual military activity.

Q: I’m curious to know if the scholars have any opinion about what happened to the Israelite kingdom when the Assyrians removed them from the land.

McCarter: It’s a very interesting subject—the legends of the ten lost tribes. What happened to the northern population of Israel is what happened to most of the world during that period. At the time the Assyrian policy of deportation of populations, of moving significant numbers of people from one place to another, was at least in part for the purpose of trying to destroy their sense of political identity and territory. It’s one of those terrible things that people have done to each other in human history. The Assyrians had the perception, which unfortunately is in a way grimly accurate, that if you take a people out of their own land they are less likely to rebel against you. They lose their sense of identity, they meld into the new population. And it worked.

Q: Where did they go?

McCarter: We’re told where they went. They were moved to the locations of other peoples. They were moved up into Syria. They were moved over into Mesopotamia. They were moved all over—and they disappeared. I don’t think they reemerged as the Cherokees or Anglo-Saxons. Once they were taken away, they lost their identity. The peoples that moved in adopted the identity of the new location. The legend of the lost tribes, as a part of post-biblical folklore, is a subject that really lies outside our kind of expertise.

What motivated the changes that previous speakers have noted in the archaeological record when the Israelites emerged in the central hill countr of Canaan? What were the reasons behind the emergence? Did religion play a part? Bill Dever candidly admitted that archaeology couldn’t provide an answer to this question. So it’s quite a challenge for our last speaker to deal with the question of religion—the origin of the Israelite religion and how religion affected this emerging people, Israel. I don’t think we could have gotten anyone better in the entire world to explore this difficult aspect of our subject today than Kyle McCarter. Kyle also received his Ph.D. from Harvard. He is one of the broadest, most eclectic biblical scholars I know. He can deal with so many different aspects of the discipline—from archaeology to ancient languages to inscriptions to the biblical text itself. He is the author of the two-volume commentary on Samuel in the Anchor Bible series. He is a past president of the American Schools of Oriental Research. He presently holds the chair—I wonder how he feels when he wakes up in the morning knowing the title of his chair—the William Foxwell Albright chair at the Johns Hopkins University. Albright was of course the doyen of biblical archaeologists of an earlier generation. Kyle is the William Foxwell Albright Professor of Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. It’s a pleasure to introduce to you my friend Kyle McCarter.—H.S.

It’s a special treat to share the podium with colleagues of the caliber that Hershel has gathered together for us. Bill Dever speaks with as much authority as anyone in the world on the subject of the archaeology of the region that we are interested in and Baruch Halpern has written the most important book to date on our subject. So it’s an honor to be here with them and to hear what they’ve said. It has created a problem for me, though, because they’ve already said everything there is to say. (Laughter.) You’ve heard it all now, and I’ve decided to talk about the legend of Robin Hood. (Laughter.) Not really.