Sources for a Life of Jesus

There are many new things happening in gospel scholarship, including developments in literary criticism, studies grounded in sociology and anthropology, rhetorical criticism and the like. We will not be dealing with these developments, however. Rather, our topic is an older, more traditional one but still one of the most controversial, exciting and inescapable questions in the study of the New Testament. Who was Jesus, historically speaking? Historians work with sources, and I want to introduce you to the sources scholars use in addressing this question. But that is perhaps the most problematic part of the task, as you will soon see.

The Historians

Jesus came of age and spent his brief career under the reign of Tiberius Caesar, who succeeded Augustus in the year 14 and ruled until 37, well after Jesus’ execution. Our most thorough Roman historian of this time, Tacitus, wrote of this period: “Sub Tiberio quies” (Under Tiberius, nothing happened) (History 5.9). This illustrates a problem. Jesus was an obscure figure in a remote part of the world, a speck on the wing of history. For centuries he would go unnoticed and remain unknown. Outside of Christian circles, almost no one took note of his life or death. Almost … but we do have a few brief notices.

Speaking of Christians, Tacitus (56 C.E.–c.117 C.E.) writes in his Annals (15.44):

The founder of this sect, Christus, was given the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius by the procurator, Pontius Pilate; suppressed for the moment, the detestable superstition broke out again, not only in Judea where the evil originated, but also in [Rome], where everything horrible and shameful flows and grows.

So much for making a good impression on Rome.

A second notice is found in the works of the great Jewish historian, Josephus (37 C.E.–c.100 C.E.). Josephus is more complimentary of his Jewish countryman but not as complimentary as the Christian monastics who preserved the manuscripts of Josephus would have us believe. When reading Josephus, one must always be wary of the presence of interpolations added by Christian scribes to bring this important voice to bear witness to the Christian gospel. In the following quotation from Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews I have indicated in italics those places where scholars agree that a Christian hand has intruded:

About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one ought to call him a man. For he was one who wrought surprising feats and was a teacher of such people as accept the truth gladly. He won over many Jews and many of the Greeks. He was the messiah. When Pilate, upon hearing him accused by men of the highest standing among us, had condemned him to be crucified, those who had in the first place come to love him did not give up their affection for him. On the third day he appeared to them restored to life, for the prophets of God had prophesied these and countless other marvelous things about him. And the tribe of Christians, so called after him, has still to this day not disappeared.

Antiquities of the Jews 18.63

So much for the historians. All told, they tell us little.

Other Jewish References

But there are other Jewish references to Jesus indicating that he did not go entirely unnoticed among his people. One of the most important is this one from the Babylonian Talmud (c. 500/600 C.E.):

On the eve of Passover they hanged Yeshu [of Nazareth] and the herald went before him 40 days saying, “[Yeshu of Nazareth] is going forth to be stoned, since he practiced sorcery and cheated and led his people astray. Let everyone knowing anything in his defense come and plead for him.” But they found nothing in his defense and hanged him on the eve of Passover.

BT Sanhedrin 43a

Then, a little later the same text continues:

Jesus had five disciples: Mattai, Maqai, Metser, Buni, and Todah.

BT Sanhedrin 43a

Not the traditional 12, but interesting nonetheless.

Still, all of these sources tell us precious little about the historical Jesus. All we learn from them is that he was a Jewish teacher of wisdom with a reputation for sorcery who had a few disciples and, perhaps, a somewhat larger following who, after his execution at the hands of Roman authorities, did not entirely give up on him. For some, that much is enough. Those who want more must turn to the documents produced by those unflappable hangers-on—in the words of Josephus—that “tribe of Christians.”

Paul

Of that tribe, the first person who left behind anything in writing was Paul of Tarsus. But in all of his letters, Paul never speaks of Jesus’ life. Paul rarely even refers to anything Jesus said during his lifetime. This is understandable because Paul never knew Jesus personally. Paul became part of the following of Jesus only after Jesus had been crucified. His experience of Jesus was limited to spiritual experiences, which he understood to be “revelation” from Jesus Christ, whom he believed God had raised from the dead (Galatians 1:11–17). In terms of history, then, Paul is a wash. For anything about Jesus’ life, we must wait several years for the writing of the first gospels.

The Synoptic Problem

There are four Gospels in the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The last of these, John, is, for complex reasons, of little value to the historian. John’s view of Jesus is quite different from the others, both in terms of the events described and the message Jesus preaches. Since the 19th century, scholars have regarded John as a spiritual reflection on Jesus with loose connections to the historical person. Today, many regard John as a quasi-Gnostic interpretation of Jesus. In any event, John seldom comes into the current discussion.

The other three Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, are closely related. Since the 18th century, scholars have noticed that they share a common view of Jesus’ ministry—we call them the Synoptic Gospels, from the Greek word meaning “seeing together.”1

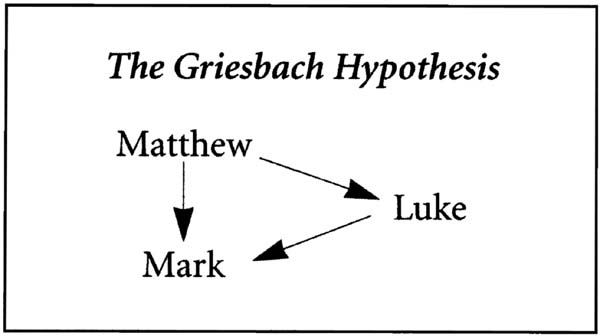

In 1776, Johann-Jakob Griesbach2 noticed that, with respect to the biographical outline of Jesus’ life, Matthew and Luke agree only when they also agree with Mark. Griesbach explained this by suggesting that Matthew wrote his Gospel first. Then Luke wrote, using Matthew loosely. Finally, Mark wrote his Gospel, combining Matthew and Luke but only using those things which they both share.

For 50 years this hypothesis held sway—and in a few circles it is still preferred today.3 But a majority of scholars began to feel dissatisfied with it because it simply did not account for the evidence, even on its own terms. For example, both Matthew and Luke begin with accounts of Jesus’ birth and end with his resurrection (hardly inconsequential matters)—but Mark includes neither of these. Perhaps more astonishing, however, both Matthew and Luke agree in opening Jesus’ ministry with the Sermon on the Mount (or Plain in Luke); but Mark says nothing about it. Scholars also began to notice that Mark’s Greek was much less polished than Matthew’s and especially Luke’s. Could one imagine Mark ruining the perfectly good prose of his predecessors?

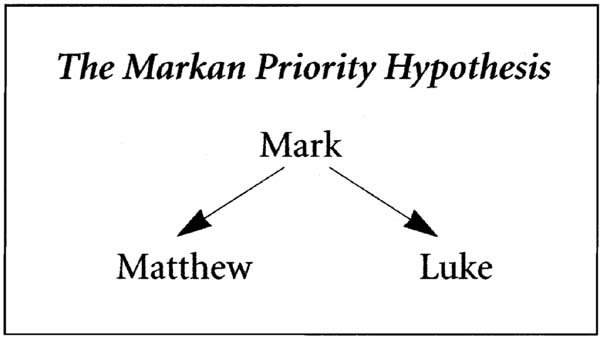

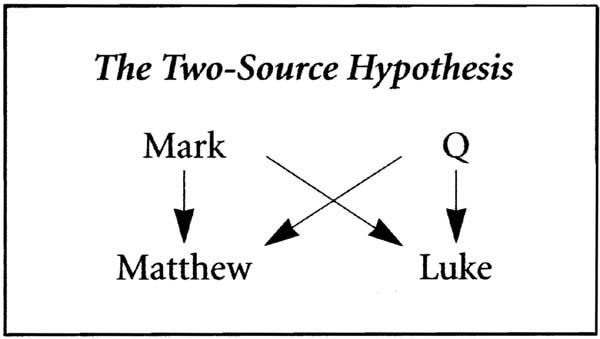

To account for these and a myriad of similar, though less obvious, problems, C. H. Weisse, H. J. Holtzmann, J. Weiss and other 19th-century scholars proposed another hypothesis.4 Rather than Matthew, they said, Mark wrote first. Then, Matthew and Luke wrote independently of one another, each using Mark as a source. That would explain why Matthew and Luke agree in terms of the general outline only when they also agree with Mark. They both used Mark as a source. This is called the hypothesis of Markan priority.

But there were still problems. The most pressing was the large amount of material shared by Matthew and Luke but not found in Mark. This material was most intriguing. In it there is a high degree of verbal agreement between Matthew and Luke. And it is presented in more or less the same order. However, they almost always insert it differently into Mark’s outline. It is as though they shared a list of sayings, parables and the like but no blueprint for where these things should go in the life of Jesus.

Based on these observations, Weisse, Holtzmann, Weiss and others proposed a second hypothesis. In addition to Mark, which provided the basic outline for a life of Jesus, they said, Matthew and Luke had a second source consisting primarily of sayings and parables. Because this source did not survive the ancient period, Weisse simply called it the “Source,” Quelle in German. Later this was shortened to the simple siglum, Q. Thus was born the two-source hypothesis, that is, that Matthew and Luke had two sources, Mark and a second source, now lost, which we call Q. Because it did not survive, this second source, Q, must be reconstructed rather imperfectly by extracting it from Matthew and Luke.

We will return to Q shortly, but for now I want to focus on Mark because Mark is our first narrative gospel, the first to present us with what at least appears to be part of Jesus’ life.

Mark

If we are to assess Mark as a source for historical research, we must first ask what sort of document it is. We call it a gospel, but this tells us little. On the one hand, so many different documents are called gospels in antiquity it is almost impossible to define just what is meant by the term. On the other hand, Mark and the other books we now call gospels were not originally called gospels. Originally they bore only an ascription.

Marcion, an unorthodox Christian teacher active in the second century, is probably the first to have used this term with regard to one of the Gospels. He applied it to Luke—specifically to Luke and not the others. In Marcion’s view, only Luke got it right, along with Paul. Marcion rejected the Hebrew Scriptures and most early Christian writings as too Jewish. Luke alone was “good news,” i.e., gospel—in Greek, euaggelion, which literally means “good news.” Eventually most Christians rejected Marcion’s views, asserting that Matthew, Mark and John were also good news, and so they also came to be called gospels. But none of this tells us what these books were like originally—or how and why they were written. For this we must turn to ancient sources and modern study. First to the ancient sources.

We are fortunate to have at least one ancient account of the making of a gospel, and it happens to be Mark. It comes to us rather indirectly from a certain elder who is claimed to have known Mark. His remarks are preserved in Eusebius, the fourth-century church historian, who got them from Papias, a church elder who lived around the turn of the first century; Papias, in turn, got them from an elder who knew Mark. Now, historians—even biblical historians—are not usually inclined to trust thirdhand accounts. Nonetheless, this little fragment is worth our attention because it illustrates how ancient Christians thought about these texts and challenges the assumptions moderns often bring to them. Papias’ brief account reads as follows:

And the presbyter used to say this, Mark became Peter’s interpreter and wrote accurately all that he remembered, not indeed in the order in which things were said and done by the Lord. For he had not heard the Lord, nor had he followed him, but as I said, later on followed Peter, who used to give instruction as necessity demanded, but not making as it were an arrangement of the Lord’s sayings, so that Mark did nothing wrong in thus writing down single points as he remembered them. For to one thing he gave attention, to leave out nothing of what he had heard and to make no false statements in them.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.39.15

Now from the modern point of view, what is intriguing about this account is that, on the one hand, it plainly says that Mark did not write things down in the right order—that is, he did not write an historically accurate life of Jesus. He simply did not have the necessary information to do so. But on the other hand, he seems to insist that Mark wrote things down accurately and made no false statements. When many people read this passage, they typically hear the last part—about Mark being accurate. They like that; it gives them a sense of security that in our culture only historical accuracy can bring. But when their attention is directed to the first part—about Mark not writing things down in the right order—then things get interesting! For to a modern person reading Mark, it reads for all the world like a short biography. How could Mark write a biography in which the events or sayings were not in the right order and still claim accuracy? The explanation is not difficult, but for the historian it spells trouble.

First of all we must realize that there is nothing in antiquity that even roughly approximates our concept of historical biography. Classics, like Plutarch’s Lives, are not easily transported into our world. These are not biographies, but aretalogies, that is, works whose purpose is to recount the wondrous deeds of great persons. Their purpose is not historical but doxological. This is true of Mark as well.

We did not need Papias’ elder to tell us this. Since the end of the 19th century, when Martin Kaehler demonstrated that the Gospel of Mark could not be used to reconstruct the life of Jesus because it is a work of theology and not history, historians have approached Mark with caution.5 The 20th century has brought even greater refinement to our understanding of exactly what Mark was doing with his writing. William Wrede suggests that Mark’s task was really apologetical, that Mark wrote to explain that Jesus was not better known as the Messiah because he kept his true identity a secret.6 Thus Jesus is always silencing people he cures or demons he casts out. Today Wrede’s theory of the Markan Messianic Secret has been replaced by more sophisticated literary analyses.

Suffice it to say here that Mark was not an historian but, rather, a theologian. Mark writes, in his own words, the “good news” of Jesus Christ and not the bare facts of his life. For the historian, this is not good news. It means that Mark can be of little value in reconstructing the life of Jesus. But this has implications for Matthew and Luke as well, who both used Mark as a source for their “lives” of Jesus. This means that we really have no historical source, no historical record of Jesus’ life. Beyond a few details—Jesus’ origins in Galilee, his end in Jerusalem—precious little is known.

So how then can Papias’ elder claim that Mark was nonetheless accurate? Accuracy is not an absolute concept but a relative one. Accuracy in achieving a goal depends on what one is trying to achieve. We tend to associate accuracy in a literary milieu with verbatim, objective accuracy. We can expect that kind of accuracy because it is achievable—with writing, recording devices, computers and the like. But this was not the case in antiquity.

In Mark’s cultural milieu, only about five percent of people could read or write. People operated orally. No thought was given to writing things down. This was simply not part of most people’s reality. Ninety-five percent of the people never wrote or read anything.7 In such a milieu, accuracy means something quite different. In a culture that is primarily oral, verbatim accuracy is not achievable for most people, so most people never tried to achieve it. In fact, it barely existed as a concept in antiquity. The famous studies of oral cultures by Albert Lord in rural Yugoslavia showed that oral tradition is never repeated with verbatim accuracy, even though the bards charged with preserving these traditions claim vociferously that they are indeed rendered accurately.8 With no texts around to define what accuracy means, it can and does mean something else altogether. To Lord’s poets, it meant something like faithfulness to the tradition. To Mark and other early Christians, it probably meant something similar. This is fine for theologians; but for historians, these findings are ominous.

Methods

Let me assure you, however, that all is not lost—not yet. But we do need to recognize that when we look to these ancient texts, the gospels, for objective historical information, we are looking for something that was of little interest to the authors and may not even have existed as a concept in their world. Nonetheless, history is an important category in our world; and we are entitled to ask questions important to us. But we may need to develop special techniques for answering these questions, techniques and methods that respect the sources for what they are and not what we wish they were.

Multiple Attestation

Even if it is true that Mark’s narrative—and, by implication, those of Matthew and Luke—is the product of the author’s creativity and imaginative theological mind, this is not necessarily true of everything he includes in his narrative. The gospel writers lived in a world that was primarily oral. Their ability to read and write places them among the elite few who had access to literacy. Most people relied upon oral tradition. In fact, most people preferred it. They were suspicious of written words, words detached from someone who could take responsibility for them and shape them into a form appropriate to a given situation. Early Christians cultivated a lively oral tradition around Jesus. Most scholars believe that much, if not most, of the information collected in the gospels originally came from oral tradition. The question is how we can know for sure in individual cases.

One way is to look for traditions in more than one written source. When it seems certain that one of these sources did not make use of the other, we may assume that both sources derived from the common stock of early Christian oral tradition about Jesus. In other words, if two authors know the same story but do not know each other, we know that neither has created the story. Rather, a source must be assumed. Occasionally, as in the case of Q, a written source may be presumed. Usually, however, all we can assume is that both authors drew on a common oral tradition.

Until recently, multiple attestation had very limited value. Occasionally one might find a tradition attested independently in both Mark and John. One could also point to a handful of cases in which both Mark and Q seem to have a common tradition. But such cases were relatively few. For the most part, we simply had to assume that the gospel writers relied upon earlier oral traditions without being able to prove it.

That changed in 1945. In that year a remarkable library of books was discovered in the desert sands of Egypt. This collection is known as the Nag Hammadi Library, after the place of discovery, Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt. Among the 50 or so tractates found at Nag Hammadi was a copy of the Gospel of Thomas. Scholars had known of the Gospel of Thomas through references to it in various early Christian authors. But no copy of it was known to have survived, that is until 1945, or rather 1957, when this text was finally published and made available to scholars for study.

There is much to say about Thomas, but let me cut to the chase for our purposes here. Two things about Thomas make it important to historical research about Jesus. First, of the 114 sayings and parables that make up the Gospel of Thomas, roughly half of them have parallels in the Synoptic Gospels. Therefore, if it should turn out that Thomas did not have direct knowledge of those Gospels or their sources, the amount of multiply attested material would be increased roughly 500 to 1,000 percent.

And that is the second thing. Careful study has shown that this is indeed the case. Thomas did not know the Synoptic Gospels or their sources. It is, indeed, an independent witness to the Jesus tradition. We know this because, unlike Matthew and Luke relative to Q or Matthew and Luke relative to Mark, Thomas does not share with the Synoptic Gospels the things that tipped us off to the literary relationship that ties the Synoptics together. That is, there is no appreciable verbatim agreement between Thomas and the Synoptics; nor is there any shared order in the sequence in which material is presented.9

Now, what does multiple attestation tell us? It does not guarantee that a saying or story is historically accurate. It only tells us that an author did not create it from whole cloth.

But it may tell us something else as well. Dating the independent witnesses to a tradition gives us a limit, a date, before which that tradition must have existed. Now, scholars, by consensus, normally date Mark to around the year 70 C.E., that is, roughly contemporaneous with the Jewish war for independence from Rome. Q, which makes no reference to that catastrophic event, is normally dated 10 to 20 years earlier. Thomas is more difficult to date, but because it does not mention the Jewish war, I have argued that an initial Thomas collection may have existed prior to the war as well. This argument is reinforced by the observation that Q and Thomas are the same sort of gospel. Unlike the more familiar narrative gospels, Q and Thomas are simply collections of sayings and occasional brief stories. They belong to the earliest efforts of Christians to use literacy to transmit and use their oral traditions.

All this means that material that is attested in both Q and Thomas, or Mark and Thomas, or Mark and Q, or, on rare occasions, in Q, Mark and Thomas, forms the earliest verifiable layer of Christian tradition about Jesus. Professor Crossan has argued, and I would concur, that any historical treatment of Jesus should at least begin here.10 This does not automatically exclude all other material in the rich and varied Jesus tradition, which by caprice might have been overlooked or dropped from one or more of these early sources. But it does provide a stable starting point.

Other Criteria

Now, just as this first stratum of material may not contain everything that the historian might trace to Jesus, neither should everything in this first stratum automatically be given positive historical evaluation. After all, material created or attributed to Jesus shortly after his death may have found its way into various gospels very early on. Thus, while multiple attestation gives us a rough starting point, we need to use other criteria for evaluating the Jesus tradition as well.

Kerygmatic Criterion

First, we must remember that the people who preserved and cultivated the Jesus tradition were not neutral. They had no objective historical interest. They cultivated the Jesus tradition because they believed that Jesus was special. To some, he was an envoy of God or God’s agent, Sophia. To others, he was the Son of Man from Jewish apocalyptic lore. To others, he was the Son of God. To others, he was the Messiah, the Christ. The followers of Jesus made use of the traditions about Jesus and created new traditions to help them express their various convictions about Jesus. So, when evaluating traditional material, the first thing scholars look for is evidence of the influence of early Christian preaching about Jesus. What early Christians said about Jesus must be distinguished from things Jesus might plausibly have said about himself. Scholars often refer to early Christian preaching as kerygma; accordingly, we might refer to this as the kerygmatic criterion.

Criterion of Social Formation

But theology was not the only thing early followers of Jesus were interested in. They also were engaged in organizing themselves and deciding on various social arrangements that would define who they were and how their group might continue. In Jesus’ brief ministry, there is no evidence that he intended to form a church. Therefore, when evaluating the tradition, scholars also try to identify material reflecting the more elaborate processes of social formation that went on in the early church but not in the historical career of Jesus himself. Scholars sometimes refer to this as the criterion of social formation.

Criterion of Distinctiveness

Then there is the simple problem that Jesus became for early Christians a symbol of authority. Thus, Christians tended to attribute to him anything that functioned authoritatively for them. This included many popular aphorisms and common wisdom. The phenomenon may be illustrated with a modern analogy. How many people blithely assume that the very American, very modern, aphorism, “God helps those who help themselves,” comes from the Bible? It does not. But to many modern Americans, the Bible symbolizes authority, especially in religious matters. Thus, when confronted with a saying mentioning God with the ring of authority, many people just naturally assume that it comes from the Bible. Early Christians, most of whom could not read or write, had no Bible, no texts at all. Rather, they had oral familiarity with a variety of wise sayings of various provenance, traditions, both sacred and secular, Jewish and pagan, all of which were considered, at a popular level, to carry some authority. They attributed many such things to Jesus, even though he may not have said them all, because he became for them a figure of great authority.

The Golden Rule is a good example of this. If Jesus did not say it, he is probably the only sage in antiquity who did not. But for just this reason, early Christians would have assumed Jesus said it even if he did not. Most of this material is not used by historians to reconstruct Jesus’ preaching because it is not distinctive enough to be associated uniquely with any individual person. We call this the criterion of distinctiveness.

Coherence and the Environmental Criterion

Finally, there is an important rule that all historians must observe in this sort of speculative reconstructive work. The resulting picture must make some sense. This means that the material one regards as historical must form a reasonably coherent whole. This is the criterion of coherence. It also means that historical material must have some degree of plausibility given what we know about the religious and cultural world of the Mediterranean basin in the first century. This is sometimes referred to as the environmental criterion.

The Present Discussion in Scholarly Perspective

Enough of matters concerning method. I am eager to give way to my colleagues on the program today, Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan. Their important and creative historical work is part of a renaissance of interest in the historical Jesus, a movement that began in the early 1980s and is just now reaching its stride. The British scholar Tom Wright has called this new impetus the third quest for the historical Jesus.11 This, of course, implies that our work has been preceded by a “first quest” and a “second.” Indeed, the quest for the historical Jesus is one of the oldest and most controversial topics in the history of New Testament scholarship. And so, a word or two to put the present work in perspective.

The first quest was carried on in Europe in the 19th century. The purpose was to apply the standards of reason and rational thought to the Gospels in order to arrive at a reasonable portrait of Jesus’ life.12 It assumed that the Gospel writers were attempting to write a history of Jesus’ life, but that they were just too naive, superstitious or swayed by doctrinal concerns to do it. Reason, it was thought, could undo all their naiveté, superstition and piety. The first quest ran aground when it was realized that the Gospel writers were not naive historians but skilled theologians, preachers if you will, who expressed themselves in a religious idiom. When you remove the religious element from these texts using modern rationality, there is nothing left. The first quest died out for lack of material.

The second quest for the historical Jesus, referred to in the literature as the new quest, began in the 1950s and involved mostly German and American scholars.13 They began with the proposition that the Gospels were not history but theology. But, they argued, it is possible that bits of history had been preserved through the oral tradition and taken up into the Gospels. Some of the methods I outlined today were developed by the new questers to recover those historical reminiscences. But ultimately their program was theological, not historical. The new questers wanted to know if the preaching of the early church, which ultimately produced the Gospels, was in any way anticipated in Jesus’ own preaching. The new quest lasted about ten years and died out for lack of interest. At the time other methods of biblical interpretation, especially literary criticism, commanded more interest and energy. There were also other ways of pursuing theology. The new questers were trying to write a history of theology, but few people were interested.

The third quest began in the early 1980s and includes titles by scholars from Britain, the Continent and North and South America. It is very diverse. The only thing that unites practitioners is historical interest. Their methods are varied, but most presume the basic methodological outline I have presented to you. They bring to the task greater knowledge of the ancient world than ever before and input from other fields of study, such as sociology, anthropology and linguistics. They tend also to be less centered on Jesus’ preaching, a focus that united the new questers, and more attentive to things Jesus is said to have done, such as overturning tables in the Temple, or typical things, such as Jesus’ practice of open-table fellowship.

Professors Crossan and Borg have been at the center of this new discussion; each will provide a glimpse of what it holds for us. But this new discussion is still too young for proper assessment. You are here to learn about work in progress. Where it will go historically, culturally and theologically is not yet known. Nor is it known if it is headed for as yet unseen shoals of disaster. All that can be said at this point is that the resurgence of interest, both lay and scholarly, has shown that, for some reason, history still matters in the postmodern world, and the Jesus of history may still make a difference.

Questions & Answers

Question: Could you comment on some of the popular books such as the Q book by Burton Mack, A. N. Wilson’s biography of Jesus, Steven Mitchell’s Gospel of Jesus?

Stephen J. Patterson: The only one of those I can speak about out of intimate familiarity is Burton Mack’s new book on Q, The Lost Gospel (HarperSanFrancisco, 1993). This is a very fine and exciting book. As a scholar, I would challenge him on a number of points, especially on the methods he uses. But in many important respects he is, in my view, quite right, even though he doesn’t prove his point the way I would like him to. Burton Mack is a scholar of the highest standing, and I would take anything he says with utmost seriousness.

As for the books by Wilson (Jesus [Sinclair-Stephenson, 1992]) and Mitchell (The Gospel According to Jesus [HarperCollins, 1991]), I can only tactfully refer you to reviews in the literature. Mitchell’s book, while creative, is not a work grounded in biblical scholarship. The quest for the historical Jesus is one of the most difficult projects in biblical scholarship. Unless you pay strict attention to a rigorous method, it is easy to end up saying almost anything you want about Jesus. The results can be exciting, but they reflect the views of the writer more than of Jesus. Some would argue that all Jesus scholarship suffers from such tendencies. That is the problem with working on a powerfully authoritative figure like Jesus. The temptation to place one’s own views on his lips is great indeed. I recommend the recent books by those who share the podium with me today, Dom Crossan and Marcus Borg, as two that reflect such methodological rigor.

Q: Why do you think Jesus did not write his own gospel?

Patterson: Most scholars assume that Jesus did not read or write. In this respect Jesus was like most people of his day. Most people in antiquity did not read or write. Ancient Literacy (Harvard, 1989), a recent study by William Harris, shows that roughly 95 percent of people in the first century were illiterate. If you could read or write, you belonged to the very upper stratum of educated society. It is not likely that Jesus, who by all accounts was a peasant, or his early followers, likewise peasants, had access to that tool. Most important, people did not presume that in order to be remembered you had to write something. Most culture was transmitted orally. For that time and place it is not at all unusual that Jesus wrote nothing and that Christian traditions about Jesus were cultivated first by word of mouth.

This is unfortunate for us because we would prefer a written record; we trust books more than storytellers. But that was not so in antiquity. Many ancients didn’t really trust the written word. They preferred the orally delivered word. Plato, for example, was rather suspicious of books. Papias, the early Christian elder upon whom we must rely for much of our information about earliest Christianity, was also distrustful of books, preferring instead to take his information from wandering apostolic descendants still active in his day. So we do not have a gospel from Jesus because he could not, and perhaps did not want to, write things down.

Q: Oral traditions are very reliable; they don’t change once they’re established or become part of a ritual. How do we know that Q was not an oral tradition?

Patterson: We know that Q was a written document because Matthew and Luke often have a high degree of verbal agreement in the passages they share. They also tend to present them in the same order, even though they may place them differently in Mark’s outline, which they also used. These two elements—verbatim agreement and a common order—are what indicate Matthew and Luke used a common written source, not just a common oral tradition.

Much has been said over the years about the accuracy of oral tradition and whether or not oral traditions might be as accurate as written traditions. Some of this was in reaction to modern biblical scholars who came to negative conclusions about the historical accuracy of the Gospels. From my remarks today, you know where I stand on this issue.

For me one of the most important studies was Albert Lord’s famous study from the 1950s, The Singer of Tales (Harvard, 1960). Lord interviewed many bards from central Yugoslavia, who were said to have committed to memory long tales and ballads, some of them hundreds of lines in length, that had been passed down for centuries. When Lord asked the bards if they were repeating the songs verbatim, exactly as they had always been repeated, they said “Yes, of course we are.” But when he recorded them and actually compared different performances of the same songs, he found that they were not repeating them verbatim. In fact, from one performance to another, there were often radical differences. The most astonishing thing was that when confronted with that evidence, the bards themselves said “Well, it is accurate.”

Others have concluded from this that in a culture that is primarily oral, accuracy is not equated with verbatim agreement. Verbatim agreement might not even exist as a concept. Without the technology to preserve the word, such as writing or a recording device, it simply does not occur to people that verbatim accuracy would be desirable. In such a culture, accuracy means something like rendering the tradition in a way that is faithful. That’s what you have in earliest Christianity—people passing on sayings, stories and the like, attempting to be faithful to the tradition but not aiming for verbatim accuracy.

That is why verbatim agreement between Matthew and Luke is so striking. When two authors rely on oral tradition, such extensive verbatim agreement is very unlikely. It happens only when two authors happen to be using a third author’s work as their common starting point. In this case, that work was Q.

Q: Where are the oldest physical texts of Matthew, Mark and Luke found? If scholars want to study the actual written word, where should they go?

Patterson: The oldest biblical manuscript for one of the Gospels is Papyrus 52, a fragment that belongs to the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. It dates to around 125 C.E. Unfortunately, it is no bigger than the palm of my hand and contains only a small fragment of John, chapter 18. Of roughly equal age is Papyrus Egerton, which contains fragments of an unknown, noncanonical gospel referred to as the Egerton Gospel. Unfortunately, all of the earliest biblical manuscripts are quite fragmentary like this. Even the earliest manuscripts are several decades, even a century or more removed from the original writing of the texts they contain. The earliest complete Gospel texts we have date to the fourth century, roughly three hundred years after the originals were written. Scholars must rely on these relatively late copies of earlier copies of earlier copies, etc., to reconstruct the original text of the Gospels. One of these complete Gospel texts is located here in Washington at the Freer Museum. It is called Codex W, and it dates to the fifth century.

Reconstructing the Gospel texts is very technical, time consuming work. It involves the analysis of literally hundreds of texts and fragments. Naturally these manuscripts, some of them extremely valuable, are scattered throughout the world in various libraries and museums. To study them all, one might go to the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center at Claremont University, which keeps a fairly complete collection of manuscripts on microfilm. But it takes a brave soul to enter that field of study.

There are many new things happening in gospel scholarship, including developments in literary criticism, studies grounded in sociology and anthropology, rhetorical criticism and the like. We will not be dealing with these developments, however. Rather, our topic is an older, more traditional one but still one of the most controversial, exciting and inescapable questions in the study of the New Testament. Who was Jesus, historically speaking? Historians work with sources, and I want to introduce you to the sources scholars use in addressing this question. But that is perhaps the most problematic part of the task, as you will soon see.

The Historians

Jesus came of age and spent his brief career under the reign of Tiberius Caesar, who succeeded Augustus in the year 14 and ruled until 37, well after Jesus’ execution. Our most thorough Roman historian of this time, Tacitus, wrote of this period: “Sub Tiberio quies” (Under Tiberius, nothing happened) (History 5.9). This illustrates a problem. Jesus was an obscure figure in a remote part of the world, a speck on the wing of history. For centuries he would go unnoticed and remain unknown. Outside of Christian circles, almost no one took note of his life or death. Almost … but we do have a few brief notices.