Acco

THE HOSPITALLERS’ COMPOUND

HISTORY

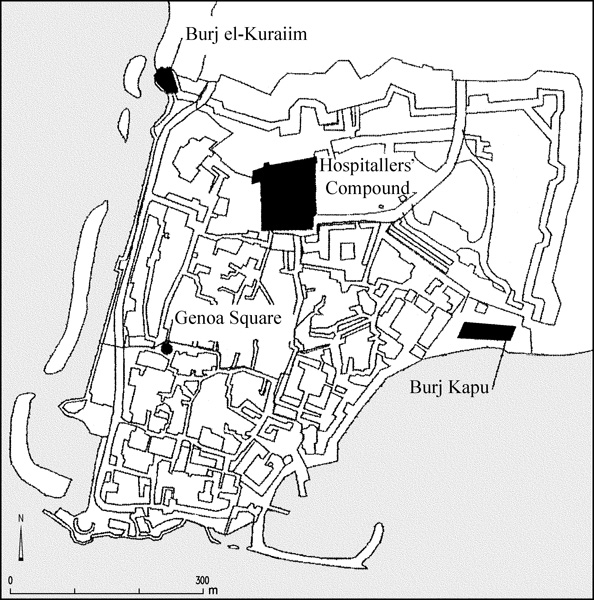

In 1104, five years after the capture of Jerusalem, Acco was besieged by land and sea by Baldwin I, king of Jerusalem, with the help of the Genoese fleet, and the city was taken by the Crusaders. In the early years of Crusader rule in Acco, the Hospitallers were the recipients of property in the city. The first reference to this property appears in documents from the year 1110, which mention that King Baldwin I permitted the Hospitallers to retain ownership of buildings received as gifts north of the Church of the Holy Cross. In 1135, some of the order’s buildings were damaged during the church compound’s expansion to the north. As a result, the Hospitallers quit the area and embarked on the construction of a new compound in the northwestern sector of the city, adjoining Acco’s twelfth-century northern city wall. This complex represents the Hospitallers’ Compound as it is known today. It is first mentioned in a document from the time of Queen Melisande (1149), which reports the construction of the Church of St. John in the Hospitallers’ Quarter south of the new compound. In 1169, the pilgrim Theodoric visited Acco and described the Hospitallers’ Compound in Acco as an impressive fortified building that was equaled only by the Templar’s fortress.

After the defeat of the Crusaders in the Battle of Hattin in 1187, Acco was captured by the Muslims and its Christian inhabitants fled the city, returning only four years later (1191) when the city was retaken during the Third Crusade. On the return of the Hospitallers to Acco, the twelfth-century buildings no longer satisfied their needs (and have not survived to the present, see below), Acco having now become the capital of the Crusader kingdom after the order lost its chief fortress and headquarters in Jerusalem. Guy de Lusignan (1192) and Henry of Champagne (1193), the new rulers of the Crusader kingdom, renewed the Hospitallers’ rights in Acco, permitting them to extend their compound to the street running along the city wall in the north. New construction was undertaken to house the head of the order and its headquarters in Acco. The building activities, commenced at the end of the twelfth century and continuing into the thirteenth century, extended the Hospitallers’ property, and new wings and additional stories were added to the old complex. The Hospitallers also erected new buildings in the new quarter (Montmusard), expanding the city’s limits on the north side and constructing a new wall by the year 1212.

HISTORY OF RESEARCH

Studies of the Crusader period in Acco began with the documentation of the ruins of the Crusader city by the numerous pilgrims who visited the city from the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Two of the most important pilgrims are the Dutchman Cornelis de Bruyn, who visited Acco in 1679 and sketched the Hospitallers’ buildings, and Garbor d’Orcieres, who meticulously rendered the city panorama from the sea in the year 1685. The main buildings of the ruined city were also identified at that time. The Crusader city was deserted in those years, its buildings razed, and some of it buried under sand. In the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, in the time of Dhahar al-‘Amr (1750–1775), Ahmad al-Jazzar (1775–1804) and their successors, a new city was erected that concealed the remains of the Crusader city beneath it.

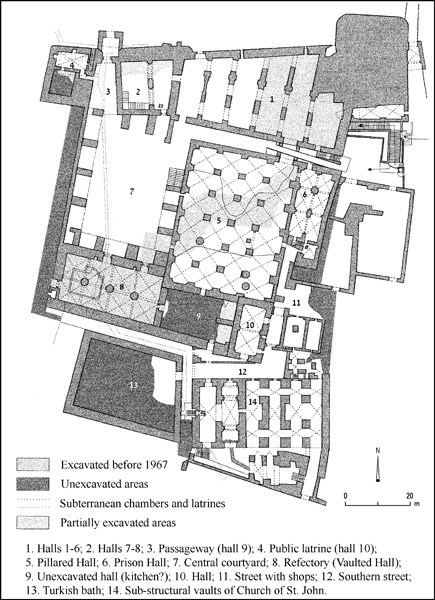

From 1955 to 1964, excavations in the Crusader remains in the Hospitallers’ Quarter, initiated by the eminent scholar of the Crusader period, J. Prawer, were carried out. These excavations uncovered halls 1–3, a narrow corridor in the Pillared Hall, and the Vaulted Hall (a refectory, erroneously called the “Crypt”). In 1990, after cracks that endangered the Pillared Hall were discovered in the Crusader remains, exploratory excavations were conducted in the exercise yard of the Mandatory prison to relieve the pressure of the earth fill on the Crusader remains. Large-scale excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority, funded by the Ministry of Tourism (Acco Development Company), followed from 1992. They were directed by E. Stern and M. Avissar in 1992–1996 and by E. Stern from 1997 onwards.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

The building exposed in the excavations described below represents the final phase of the Hospitallers’ Compound at the time of its abandonment in 1291. The beginning of its construction dates to the first half of the twelfth century; it was built in several stages.

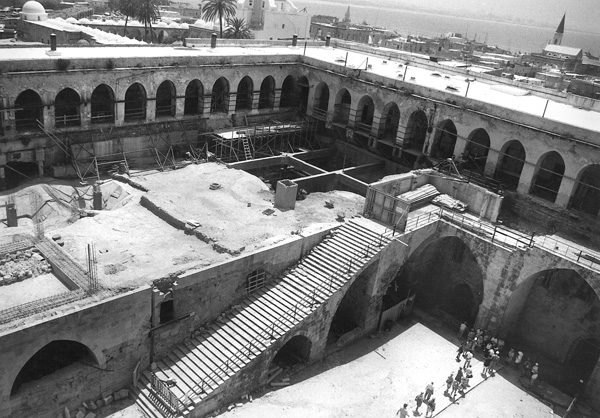

THE CENTRAL COURTYARD. The complex was constructed around a central, open courtyard (1,200 sq m). On the northern side of the courtyard was a well (4.5 m deep); two shallow plastered pools (40 cm deep) adjoining it drained into the main sewage system (see below) through a water channel beneath the courtyard. In the southern part of the courtyard was another well and next to it a plastered pool (1.5 m deep) in the shape of a bathtub. The well on the north side apparently supplied drinking water and was also used for washing clothes, while the one in the south was for bathing. The courtyard was surrounded by arches. A flight of stairs in its eastern part led to the upper stories.

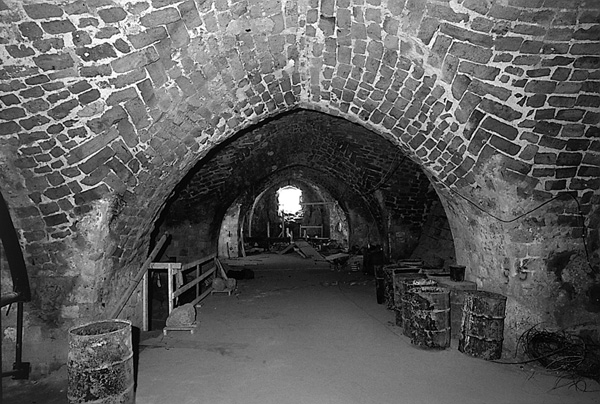

THE NORTHERN WING. Built against the northern city wall, the northern wing consisted of a row of ten halls. Halls 1–6 comprised a single unit divided into separate halls by walls with arched doorways and a 10-m-high barrel-vault ceiling. Repairs had been made to the ceilings of the Crusader structure and to some of the doorways between the halls. The outer walls of this complex were massive and built of ashlar masonry 3.5 m thick, indicating that the complex was originally constructed as an independent building; only later were halls 7 and 8 added on its western side. Windows set into the southern wall of the halls opened onto the street passing between the halls and the Pillared Hall on the south side. The entrance to the halls was situated in the southern wall of hall 2, where a 4-m-wide opening connected the halls and the great hall in the south through a roofed corridor. Another doorway in the northern wall of hall 2 led to a flagstone square in the northern moat. A wide staircase built of ashlars ran along the outer face of the northern walls of the halls leading to the square. At the top of eight stairs was an open landing where the stairs changed direction and turned to the north. The continuation of the stairs was not preserved but they probably proceeded over a stone bridge above the city’s northern moat up to the Hospitallers’ Tower (Turris Hospitalis), guarding St. Mary’s Gate, which opened toward the northern route to Tyre through the Montmusard.

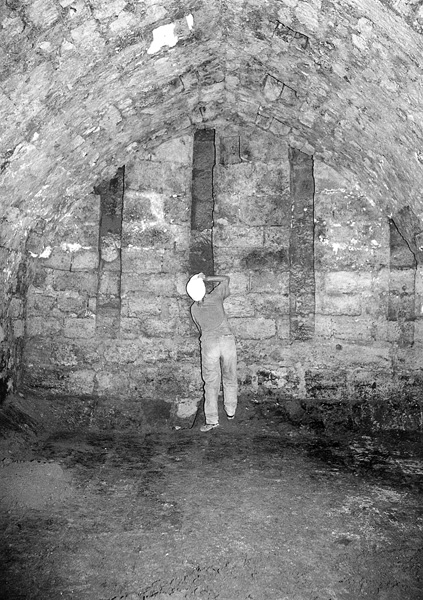

HALLS 7–8. The three-story halls 7–8 were a later addition. The lowest story was occupied by a large reservoir for storing rainwater that was divided into two halls, each 13 by 5 m, 7.5 m high, and roofed with a barrel-vault. The halls were covered from floor to ceiling with thick hydraulic plaster, most of which was well preserved on the walls. A wide, arched opening linked the reservoir’s two halls, turning them into a single unit with a capacity of c. 1,000 cu m. The aperture for filling the reservoir was located in the northern part of the ceiling of hall 8, and its mouth, which drained the reservoir and allowed maintenance works to be carried out, was in the southern part of the ceiling of hall 7. The second story was occupied by halls and storerooms corresponding to the halls beneath them. These second-story halls, 7 m high, had a barrel-vaulted ceiling that had collapsed. Large segments of the ceiling were found lying on a more than 3-m-high fill, evidence that the collapse occurred a considerable time after the Hospitallers had abandoned the building in 1291.

After the fill was removed in the excavations, hundreds of pottery vessels were found in situ in rows on the floor of the building. The vessels, which were cone shaped and had an opening at the bottom, were receptacles for sugar and had been stacked one inside the other in rows along the eastern wall of hall 7. Straw was laid on the floor between the rows to prevent breakage. In another part of the hall, scores of vessels known as molasses jars lay on the floor. These jars were employed in the last stage of the production of crystallized sugar, one of the most important industries in the Holy Land during the Crusader period. This large warehouse and its considerable number of vessels used in the production of sugar reinforce the evidence obtained from many historical documents that refer to the leading role played by the Hospitallers in the production of sugar in the Acco area. This successful enterprise filled the coffers of the Order of the Hospitallers.

A staircase built against the southern wall of hall 8 led to the third floor. Nothing has survived of this floor, but the considerable collapsed remains uncovered in the debris indicate that it was constructed in an elegant Gothic style. The stone voussoirs of the Gothic-style arches were decorated with a colored fresco in black, yellow, and red. In addition to the voussoirs, the keystone—the central stone of the rib-vaulted Gothic arch—was also found in the debris where it had fallen from the ceiling. Unusually large in size, this keystone bears a decoration in the form of a rosette with acanthus leaves. Three keystones have been uncovered so far. The numerous fragments of the elaborate ceiling discovered in the excavations will certainly allow at least its partial reconstruction.

HALL 9. Hall 9 served as a passageway between the central courtyard and the northern moat, through an arched gate protected by a massive tower above it. The passageway was roofed with a barrel vault.

HALL 10 AND THE CENTRAL SEWAGE SYSTEM. The wing in the northwestern corner of the complex was three stories high and contained the public latrines. The first floor served as an underground sewage chamber into which scores of drains in the walls of the buildings emptied waste matter from the public latrines on the second and third floors. Additional pipes in the building’s outer walls carried rainwater from the roofs through the three stories to wash the floor of the underground chamber. The chamber was connected by means of five channels to a main channel that drained the city’s northern moat and crossed the Hospitallers’ complex from north to south to drain the central courtyard, its wells and pools, the other wings, and the public latrines. The course of this main channel was examined in a number of soundings made in the city, revealing that it was a municipal sewage channel (1 m wide and at least 1.5 m high) that ran through the city from north to south and emptied into the sea near the harbor. The inclined floor of the underground sewage chamber was paved with smooth stone blocks for easy draining into the main channel. Above this sewage chamber was the first floor of latrines, a room (10 by 5 m) roofed with cross vaults 10 m high and fitted with two rows of seats along the northern and southern walls and two additional rows in the middle of the room. In each row were eight seats that emptied through pipes directly into the sewage chamber. Ventilation was provided by three windows facing the northern moat in the room’s northern wall. Above this room was another latrine room that has not survived in its entirety, as a hall was constructed here during the Ottoman period. The floor of this latrine room apparently contained a row of stone toilet seats only along two of its walls; excavations carried out beneath this room exposed some of the toilet seats. The toilet seats were 40 cm above a channel leading to a drain built into the wall that emptied the waste matter into the underground sewage chamber. This latrine complex, exposed in its entirety, is a very rare discovery with but few parallels in monasteries and hospitals of the thirteenth–fourteenth centuries in England and Wales.

THE WESTERN WING. Although it has not yet been excavated, some of the findings in the western wing indicate that it was at least two stories high (the second story of one of the walls was preserved). The building remains uncovered in the debris in the western part of the open courtyard and the capitals preserved in situ on the wall of the building—bearing basket motifs and human figures—attest that the western wing was also constructed in Gothic style. The wing was entered from the open courtyard through two wide, arched openings and apparently served as the order’s living quarters.

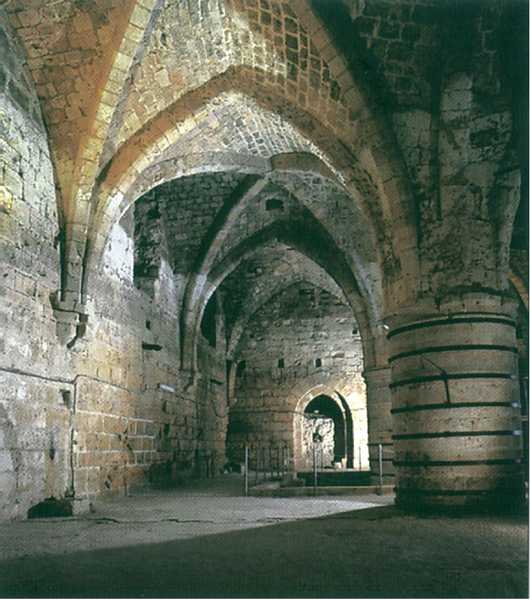

THE SOUTHERN WING. The southern wing of the compound housed the most imposing hall. It was excavated in the 1960s by the National Parks Authority and identified by some scholars as the “Crypt of St. John,” in the belief that it had served as the foundation of the church of the same name erected above it. The recent excavations, however, have clearly established that this identification is erroneous (see below, Church of St. John). The hall was built in a series of eight cross-ribbed vaults, 10 m high, supported by three round stone columns, c. 3 m in diameter. The stone ribs supporting the cross-vaulted ceiling were carried by consoles emerging from the walls. The consoles are decorated with floral wreaths, baskets, and fleurs-de-lys. Rosettes were carved on some of the cross vaults at the intersection of the ribs. The building is considered an example of the transitional style from Romanesque to Gothic. It was the order’s refectory, with the unexcavated hall to its east perhaps serving as the kitchen. Recent excavations beneath it uncovered an underground reservoir for storing rainwater.

THE EASTERN WING. The eastern wing comprised a huge Pillared Hall (c. 1,300 sq m in area) constructed as a series of some 15 identical bays with cross vaults, 8 m high, supported by rows of square stone pillars. The central section of the vaulted ceiling survives in its original form while the southern and northern sides have collapsed. Parts of the collapsed ceiling were uncovered on a fill 3 m high, evidence that the collapse occurred long after the Crusader period, perhaps during the Ottoman building activities of the eighteenth century.

THE PRISON HALL. East of the large Pillared Hall was another hall not directly connected to the Hospitallers’ Compound, but to the public street running along its eastern side. The hall, 2.5 m lower than the adjoining buildings—the floor having been dug in virgin soil—had a series of six cross vaults, 5 m high. Given that there were no windows or other means of illumination aside from the entrance on its southern side, and that it was separated from the complex as a whole and constructed at a lower level than the houses in the quarter, it can be assumed that the hall served as the prison of the Hospitallers’ Quarter, mentioned in contemporary historical sources. Pairs of square recesses (3–4 by 3–4 cm and 2–3 cm deep) were cut in the stones along the walls and pillars supporting the ceiling, and perhaps held metal hooks to which the prisoners were chained.

THE SOUTHERN STREET. A public street was discovered south of the Hospitallers’ complex. It crossed the Hospitallers’ Quarter, running from Porta Hospitalis in the northern city wall, southward along the eastern wall of the quarter. The street turned west and passed between the complex and the Church of St. John, and after about 50 m turned south toward the Genoese Quarter. At this point a monumental stone gate was constructed that allowed the Hospitallers to block public access to the street in times of danger. Most of the 4-m-wide street was not roofed, but short sections had a barrel vault. Another public street, which was especially wide (c. 10 m) and paved with stone blocks, branched off to the east (the King’s Quarter). A row of shops, three of which were excavated, stood on the southern side of the street.

OTHER CRUSADER REMAINS

THE CHURCH OF ST. JOHN. Construction of the Church of St. John is first mentioned in a document dated to 1141, during the reign of Queen Melisande. The church rose to a great height, and had been built above a series of vaults oriented east–west and comprised of two parts. The western part, which already stood before the church was built, consisted of two halls roofed with a barrel vault; the eastern part, added when construction of the church began, of four areas roofed with cross vaults 5.5 m high. These sub-structural vaults remained intact when the church was destroyed and are popularly known as the “el-Bosta” halls. Their excavation took place in the 1950s and uncovered two tombstones from the Crusader period. One is of marble and bears an inscription in Latin mentioning the death in 1242 of the ninth head of the Order of the Hospitallers, Pierre de Vieille Brioude. The other is a marble tombstone with a French inscription, which attests to the burial place of the Bishop of Nazareth, who died in 1290.

The Church of St. John was destroyed in 1291 and an Ottoman government building (Seraya) was erected on its site at the beginning of the nineteenth century. A sounding in the courtyard of the Seraya uncovered section of a floor paved with marble tiles in various colors, three collapsed marble columns in situ, a marble Corinthian capital decorated with a colored fresco, and another similarly decorated capital on which a Maltese cross appears in orange on a black background. On the marble floor lay numerous fragments of a multi-colored stained-glass window. The main entrance of the church, 4 m wide, was uncovered on the east side of the building; its threshold and door hinge sockets are of black granite.

THE TEMPLAR’S TUNNEL. Uncovered beneath the Ottoman buildings in the Templars’ Quarter in the southwestern part of the Old City was a 350-m-long stone-built subterranean tunnel that crossed the city from west to east. On its western side, it started at a small bay where a fortress of the Order of the Templars stood in the Crusader period. The tunnel (4 m wide and 2.5 m high) was built on bedrock and roofed with a half-barrel vault; 70 m along its course it reached a very high room constructed above the roof of the existing tunnel. At this point the Templars apparently operated a checkpoint on the border between their quarter and the Pisan Quarter to the east. The tunnel proceeded eastward for another 250 m beneath the Pisan Quarter and reached Acco Harbor. This section, hewn in bedrock, branched off into two narrow, parallel tunnels, each c. 1.5 m wide and 2 m high. The tunnel apparently served as a passageway for people and goods leading directly from the Templar’s Quarter to the harbor.

THE ROOFED STREET IN THE GENOESE QUARTER. An archaeological survey conducted by B. Z. Kedar and E. Stern uncovered a street of roofed shops in the center of the Old City, which they subsequently excavated. The street, built along an east–west axis, was exposed for a distance of about 40 m, but in the survey its length was found to be about 100 m. The street was built of ashlars, c. 8 m high and 5 m wide, and was roofed with a stone cross vault supported by stone ribs. Entrances on both sides of the street led into the shops and workshops. It apparently dates to the Crusader period (thirteenth century) and may be the “roofed street” in the Genoese Quarter mentioned in several contemporary Crusader documents.

THE CRUSADER BATHHOUSE IN THE MONTMUSARD QUARTER. In 1996–1997, a salvage excavation was conducted south of the Acco Police Station, c. 300 m north of the walls of the Old City, under the direction of H. Smithline and E. Stern on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The excavations uncovered a Crusader period bathhouse (22 by 7 m) oriented east–west. In the middle of the bathhouse was a furnace, 5 by 5 m, with a combustion chamber (3.5 m in diameter) preserved to a height of 2.5 m. The furnace had three openings, the one facing west leading to an open courtyard lower than the floor of the bathhouse and apparently used for storing the firewood. Air was conveyed to heat the lower floor of the caldarium through the other two openings in the furnace, one facing northward and the other eastward.

The hypocaust was installed in the caldarium (14 by 7 m), which surrounded the furnace on its northern and eastern sides. The lower floor consisted of hard limestone blocks, 30 by 25 cm and c. 7 cm thick, on which small limestone columns 80 cm high were placed to support the upper floor. The upper floor was of limestone slabs laid above the columns and a 30-cm-thick fill of orange clay mixed with pieces of limestone overlying the slabs. This fill served as a bedding for a polychrome marble floor that was mostly plundered in the Ottoman period (eighteenth century); sections of this floor have survived in the area.

The walls of the bathhouse were built of well-dressed limestone that was almost entirely looted during the Ottoman period, judging by the eighteenth-century Ottoman period clay smoking pipes found in robber trenches of the walls. It is therefore difficult to reconstruct the complete plan of the building. On the east side of the bathhouse was a stone water channel, covered with white plaster, which supplied water to the structure. In the northern part of the caldarium were found the remains of a pipe for the circulation of hot air.

A rich pottery assemblage from the Hellenistic period (third–second centuries BCE) and walls built on virgin soil were uncovered in probes dug under the Crusader floors. The bathhouse is dated by its ceramic finds to the thirteenth century, corroborating what is known from historical sources concerning the construction of the Montmusard Quarter.

ELIEZER STERN

THE HARBOR

EXCAVATIONS

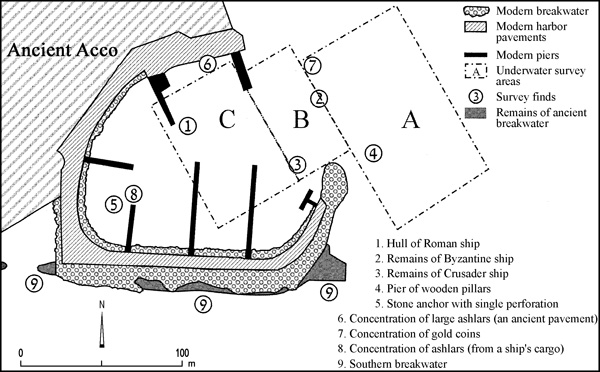

In November 1992 and June 1993, the port of Acco was deepened to enable the servicing of boats with a draft of several meters. The work was executed under close archaeological inspection (under the direction of E. Galili and Y. Sharvit) and the material raised from the bottom of the harbor was examined. A crane with a grab dredged the sediments containing the archaeological material from the bed of the harbor, and deposited them onto a barge with a bottom that could be opened. The material was dumped into the open sea and checked by divers. The harbor was divided into three main areas: area A—the western part of the eastern basin, east of the modern port; area B—the entrance to the western basin; and area C—the inner part of the western basin. The following description of the findings was written in collaboration with N. Bahat-Zilberstein, Y. Sharvit, E. J. Stern, G. Finkielsztejn, and R. Kool, all of the Israel Antiquities Authority; Y. Kahanov of the University of Haifa, Department of Maritime Civilizations; and D. Zvieli of the University of Haifa, Geography Department.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE BRONZE AGE, IRON AGE, AND PERSIAN PERIOD. Very few finds from the Bronze Age were recovered, aside from two stone anchors with a single perforation and a loaf-shaped bronze ingot. Iron Age finds were completely absent and only a few Persian period sherds were retrieved. The paucity of finds from periods prior to the third century BCE and the complete absence of Attic imported ware, which is widespread in the coastal region, attest that there was no large-scale maritime activity at the port of Acco prior to the Hellenistic period.

It has been suggested that during the Bronze Age, the rivers on the Levantine coast, including the Na‘aman, served as inland harbors. However, there is no archaeological evidence (shipwrecks, mooring equipment, anchors, etc.) of a Bronze Age port inside a river on the coast. According to E. Galili, the anchorages in this period were located in the sea, in areas partly protected by kurkar sandbars. This suggestion is based on the results of underwater surveys carried out in the last 40 years on the coast of Israel and on the assumption that the mouths of the rivers were ordinarily blocked by sandbars (as they are today). It follows that riverbeds near their outlets were shallow and impassable for sea-going vessels. It appears that in the Bronze Age there were natural kurkar bars southeast of the peninsula on which the city stood. They provided partial protection from the southwestern, western, and northern winds in summer and during the transitional seasons of the year; and also served as a natural anchorage, like those found at

Abundant archaeological evidence exists for widespread trade activity in the coastal cities of the Levant, including Acco, in the Iron Age. In stark contrast, there is a paucity of finds from this period in Israel’s shallow seabed and a total absence of such remains in Acco harbor. No plausible explanation has yet been offered for this phenomenon. According to A. Raban and E. Linder, the harbor’s southern breakwater was built in the Persian period to accommodate Cambyses’ fleet. Since the excavations of the harbor yielded only meager sherds from the Persian period, the finds cannot support the contention that the harbor was built in that period. It is possible, however, that Iron Age and Persian artifacts lay stratified at the bottom of the western basin under a thick layer of sediment, and were not reached by the dredger during the deepening of the harbor.

THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD. Judging from the wealth of finds and their diversity, maritime activities in the western basin of the harbor underwent a fundamental change in the Hellenistic period. The large amount of pottery, including amphoras, domestic vessels, and metal objects, points to extensive trade relations with Mediterranean countries and the large-scale import of food from the area of the Aegean. These finds, as well as the fine silt sediment in the harbor, attesting to a calm sea and good mooring conditions, indicate that the southern breakwater dates from the Hellenistic period. The archaeological finds retrieved from the sea thus support the thesis, proposed by D. Jacoby, R. Gertwagen, A. Flinder and others, that the harbor was built in that period. In the opinion of Linder and Raban, the foundations of the Tower of the Flies were constructed by the Phoenicians in the Persian period, but no archaeological evidence to support this claim has so far been discovered. In the opinion of Gertwagen and Jacoby, and of E. Galili and B. Rosen, the foundations of the Tower of the Flies were built in the Hellenistic period, at the same time as the southern breakwater. The city of Tyre and its harbor—the major port of the Eastern Mediterranean—had been thoroughly demolished by Alexander the Great at the end of the fourth century BCE, presumably encouraging the rise and development of the harbor of Acco, as reflected in the underwater archaeological finds. Most of the identified Hellenistic amphorae recovered (c. 80 percent) originated from the Aegean region; 8 percent are from the coasts of Syria and Palestine, 5 percent from Egypt and North Africa, and a few percent from Italy.

THE ROMAN PERIOD. Among the finds from the Roman period are a large number of storage jars and domestic vessels, including bowls and Western terra sigillata ware, pottery which is found only rarely among the Roman ceramic repertoire of inland sites. Numerous metal objects were also retrieved. Some of the objects are decorated with maritime inscriptions and themes. The base of an Eastern terra sigillata plate bears an incised depiction of a boat with its bow moored to a tree, in typical Mediterranean fashion. Incised on the sides of a deep bowl are images of iron anchors.

In the northern part of the harbor, at a depth of 3.5 m, were found the remains of the wooden hull of a ship, including wooden parts and bronze nails with a square cross-section. Laboratory tests indicated that the vessel’s framing timbers were constructed of pine of European origin, for which a 14C examination yielded a date of 144–213 CE (calibrated). The hull’s planking, which was attached by means of mortises and tenons, was constructed of the same type of wood and dated to 147–250 CE. The boat can therefore be dated to the Roman period (second to third centuries CE). The size of the nails and the surviving pieces of wood suggest that the boat was of medium size (15–22 m long). It appears to have been wrecked in the western basin of the harbor.

In addition to the harbor’s military role in the Roman period, mentioned in historical sources, the ceramic finds attest that in this period the harbor enjoyed far-flung trade relations with Mediterranean countries. The retrieval of luxury imports reveals that in the Roman period the harbor of Acco satisfied the demands of a society that included wealthy consumers. These finds agree with written references to the harbor at Acco and its functions. The finds from the harbor also indicate that in the Roman period the main maritime activities were apparently concentrated in the western basin, which was protected by the southern breakwater and could provide shelter for medium-sized boats with a draft of 2.5–3 m. Half of the identified Roman amphorae originated from the Aegean and Black Seas, a fifth from Italy and the western Mediterranean, 16 percent from the coasts of Syria and Palestine, and 10 percent from North Africa.

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. According to historical documents, the harbor suffered from neglect and the city declined in importance in the Byzantine period. Nonetheless, numerous underwater finds along the coast of Israel (mainly shipwrecks and iron anchors) are evidence of large-scale commercial activity during that time. A considerable amount of Byzantine pottery was found in the harbor. Most of the finds from this period, including a few pieces of wood, bronze nails, and a number of coins, were retrieved from area B. These objects probably came from a vessel anchored there during a storm and wrecked at the entrance to the harbor. In the western basin (area C), a number of broken iron anchors were retrieved. On the basis of these broken anchors and the paucity of finds from the Byzantine period in the western basin, it can be concluded that anchorage conditions in this period were extremely unfavorable. Due to lack of proper maintenance subsequent to the Roman period, the southern breakwater was probably destroyed and ceased to provide protection for sea craft, compelling sailors to cast anchor in the western basin or in the open sea to guarantee their safety. Eighth-century amphorae discovered in the remains of the Byzantine wreck indicate that maritime trade by Byzantine sailors continued in the Early Islamic period. Nearly half of the identified Byzantine amphorae originated from the Aegean and Black Seas, 40 percent from the coasts of Syria and Palestine, 3 percent from North Africa, and 6 percent from the western Mediterranean.

THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD. The historian al-Muqaddasi described the construction of Acco harbor by Ibn Tulun and its closure with a chain. In the opinion of Linder and Raban, the Ibn Tulun and Crusader harbors occupied the western basin only; however, no Early Islamic period archaeological remains were found in the western basin. Most of the activity in the harbor during this period apparently took place in the eastern basin (from the eastern rampart westward), probably because the western basin was silted. There is also disagreement regarding the chain across the Islamic period harbor. Either the chain closed the entrance to the western basin (from the end of the rampart at the eastern end of the southern breakwater northward towards the round tower in the wall near the Ptolomais Restaurant, a distance of about 70 m) or extended eastward, towards the Tower of the Flies (a distance of c. 100 m). Flinder and Jacoby, however, have claimed that the chain closed the southern entrance to the harbor. Since no Early Islamic period finds were uncovered in the western basin, the harbor described by al-Muqaddasi would appear to have been located in the eastern basin, with the chain stretched between the Tower of the Flies and the eastern end of the southern breakwater, as proposed by Gertwagen. To bridge this great distance and prevent passage above the chain, the chain was probably floated by the use of a number of beams or wooden barges. A similar technique, by which floating wooden beams held a chain across the Acco harbor, is mentioned in a contemporary document.

Gertwagen suggested that the eastern rampart served as a breakwater. However, since the eastern shore of the bay lies close to the harbor and prevents easterly winds from producing high waves that could endanger boats anchored in the harbor, it can be assumed that the eastern rampart connecting the Tower of the Flies and the shore was not built as a breakwater but as a barrier to prevent the entry of enemy ships from the east. It could have also served as an approach road for the construction of buildings on the Tower of the Flies. A building similar to the one on the Tower of the Flies exists in the harbor of Sidon, where an approach road from the mainland was constructed on stone-built arches. Future excavations in the eastern rampart and the eastern basin may clarify some of these questions.

THE CRUSADER PERIOD. Crusader period remains were uncovered mainly near the entrance to the western basin (areas A and B), outside the Hellenistic and Roman harbor. Only isolated sherds were retrieved from the western basin. This pottery came from Cyprus, Syria, Anatolia, the Aegean, and Italy. A hoard of 21 gold coins identified as florins minted in Florence in the second half of the thirteenth century was also found. This discovery corresponds with historical documents describing the flight of wealthy Christians from the city with their valuables during the capture of the city by the Mamelukes on May 18, 1291; in their flight, they paid local boat owners to transport them from the coast to large vessels anchoring offshore.

According to historical sources, Acco harbor was the country’s major harbor in the Crusader period; documents contain numerous references to military, economic, and civil activities in the harbor area. Finds uncovered in recent years in excavations on the mainland support the historical sources. Thus, the meager remains found on the harbor bed are somewhat surprising. This discrepancy between the historical evidence and the finds in the harbor may be explained in two ways: perhaps the Crusader remains lay above earlier finds in the western basin of the harbor and were removed in the 1970s and 1980s when the harbor was deepened. Another, perhaps more plausible, explanation is that in the Crusader period the western basin was silted due to neglect and improper maintenance (as in the Early Islamic period), and all maritime activity was restricted to the eastern basin of the harbor. Since the eastern basin was not deepened during the present construction work in the harbor, this may explain the paucity of finds from the Crusader period. There is evidence for the mooring of medium-sized vessels outside the harbor in documents that mention the transport of a shipment of iron anchors from Venice to Acco in 1288.

THE MAMELUKE AND OTTOMAN PERIODS. Many finds from the Mameluke and Ottoman periods were uncovered at the entrance of the western basin and to its east (areas A and B). In these periods it appears that large vessels with deep drafts anchored east of the western basin, and merchandise was transported from the ships to the shore on small boats. The ceramic finds from these periods point to trade relations with lands in the Eastern Mediterranean including areas of present-day Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt.

At the entrance to the Fisherman’s harbor (area A), at a depth of 3–4 m and a distance of c. 20–30 m northeast of the end of the modern breakwater, was found a group of 11 upright wooden pillars with a rectangular cross-section (20 by 15 cm) embedded in the seabed. The pillars had been arranged in a triangle, 28 by 28 by 14 m. Other pillars had probably belonged to this construction but were dislodged over the years by fishermen’s nets, anchors, or the frequent deepening activities at the entrance to the harbor. Radiocarbon tests dated the columns to the fifteenth century (1475±50 yr.

In 1291, Acco was razed by the Mamelukes and abandoned; it remained deserted for centuries. The city’s harbor was destroyed and blocked to prevent the return of Christians to the city. Nevertheless, testimony by travelers and pilgrims who sailed from the harbor of Acco in this period indicates that, despite the destruction, the harbor continued to be used during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The abandoned city contained warehouses of Venetian traders who had arrived from Damascus and exported cotton to Europe through this harbor. Recent archaeological finds from

The construction of wooden marine installations is not a common occurrence in the material culture of the area, where large trees are rare and very costly. Evidence of the import of timber from Europe for building breakwaters was uncovered in the Roman harbor at Caesarea and at the Byzantine harbor at

The numerous cannon balls and rifle shells found on the harbor bed complement historical sources documenting battles in the harbor area and the bombardment of the city from boats anchored at sea in Napoleon’s siege of Acco.

DISTRIBUTION OF THE FINDS IN THE HARBOR. The distribution of the finds from different periods in the harbor area reveals a withdrawal from the inner anchorage area (the western basin—area C) to the entrance of the modern harbor (area B) and outside it, to the eastern basin (area A). Most of the finds from the Hellenistic and Roman periods were uncovered in the western basin, inside the modern marina. Numerous Byzantine finds at the entrance to the marina may indicate intensive marine activity in area B during that period, or may simply come from a single shipwreck. Crusader remains were retrieved mainly in area B, near the entrance to the western basin. This distribution attests to fundamental changes in the anchorage conditions inside the harbor, such as the accumulation of sand, which prevented ships with deep drafts from anchoring safely within the harbor.

Based upon the finds uncovered in the excavations of Acco harbor, it can be deduced that the breakwaters were constructed in the Hellenistic period and created the western basin, which reached the peak of its prosperity in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The Byzantine period saw a worsening of anchoring conditions and the southern breakwater seems to have been in ruins at that time. At the end of the Umayyad period and during the Abbasid period (end of the eighth to end of the eleventh centuries CE), the area of the harbor was expanded to the east and the eastern rampart was constructed, connecting the Tower of the Flies with the northern shore of the bay. A drawing from 1686 shows the southern breakwater as a line of low bars around a closed basin. In illustrations and maps from later periods, on the other hand, a number of relatively tall buildings that are the same height as the buildings on the Tower of the Flies are shown on the eastern end and in the center of the southern breakwater. At the end of the seventeenth century, large buildings were apparently erected on the southern breakwater, but do not survive today.

EHUD GALILI, BARUCH ROSEN

Tel Acco

Excavations in the Modern City

Maritime Acco

Plain of Acco

Tell el-‘Idham

Tel Regev

Color Plates

THE HOSPITALLERS’ COMPOUND

HISTORY

In 1104, five years after the capture of Jerusalem, Acco was besieged by land and sea by Baldwin I, king of Jerusalem, with the help of the Genoese fleet, and the city was taken by the Crusaders. In the early years of Crusader rule in Acco, the Hospitallers were the recipients of property in the city. The first reference to this property appears in documents from the year 1110, which mention that King Baldwin I permitted the Hospitallers to retain ownership of buildings received as gifts north of the Church of the Holy Cross. In 1135, some of the order’s buildings were damaged during the church compound’s expansion to the north. As a result, the Hospitallers quit the area and embarked on the construction of a new compound in the northwestern sector of the city, adjoining Acco’s twelfth-century northern city wall. This complex represents the Hospitallers’ Compound as it is known today. It is first mentioned in a document from the time of Queen Melisande (1149), which reports the construction of the Church of St. John in the Hospitallers’ Quarter south of the new compound. In 1169, the pilgrim Theodoric visited Acco and described the Hospitallers’ Compound in Acco as an impressive fortified building that was equaled only by the Templar’s fortress.