Ashdod

EXCAVATIONS

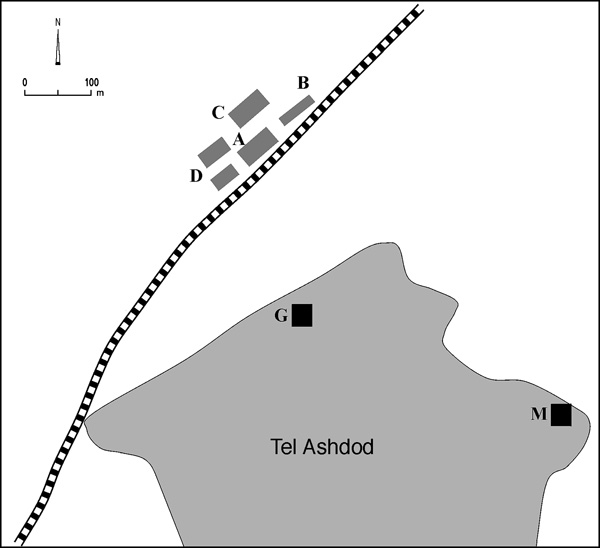

Subsequent to preparatory work for the laying of railroad tracks for a line between Ashdod and Ashkelon, a salvage excavation was conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority near Tel Ashdod. The first season took place in November 2003–January 2004, under the direction of E. Kogan-Zehavi, and the second in April–June 2004, under the direction of E. Kogan-Zehavi and P. Nahshoni. Other small-scale excavations were conducted by D. Varga in 2003, in an arched tomb from stratum 2, a cist tomb from stratum 7, and a furnace from stratum 3. The excavation area is located some 200 m northwest of Tel Ashdod, and as based on previous knowledge, outside the area of the mound. Four excavation areas (A, B, C, D) were opened during the excavation, yielding archaeological remains from five periods—the Iron Age and the Persian, Hellenistic, Late Roman, and Byzantine periods—described below from the earliest to the latest.

AN ASSYRIAN-STYLE PALACE

The prominent remains from the excavation are basement rooms and a bathing room of an Assyrian-style palace, which once spread over an area of at least 2.5 a.

STRATUM 7. The Assyrian-style palace of stratum 7 stands atop a monumental platform rising to a height of c. 3 m and built of red square mud bricks (38 by 38 by 10 cm). The shape of the bricks is typically Mesopotamian, as opposed to the rectangular bricks prevalent at Tel Ashdod. The palace itself is also built of square bricks, gray in color rather than red.

Area C was excavated on the western side of the site. Surprising findings came to light in three rooms in the east of the area: three bathtub-like basins, two ceramic and one stone. The eastern room (no. 1) was completely covered in gray plaster, meant to seal the room and prevent the absorption of water. One of the ceramic bathtubs was preserved in a complete state on its floor. Only the western part of the room was revealed, thus its original dimensions and any other elements contained therein cannot be known. It appears to have functioned as a bathing room, as is common in Assyrian palaces. Another room (no. 2) was revealed adjacent to the bathing room, the two rooms separated by a plastered pilaster. Only a small portion of this room was uncovered, delineated by walls built of two faces of well-dressed ashlars, measuring 40 by 60 cm. Found in the western room (no. 3) were the two other bathtub-like basins, not in situ. It appears that they collapsed from higher up, perhaps the second story, together with the walls from the structure. Since the room was not covered in the waterproof plaster extant in the eastern room, it is suggested that the room was of a different function than the eastern room. The walls of these rooms were abutted by a floor of square mud bricks laid over the podium.

Area A was opened on the southern side of the site. A courtyard, spreading over 30 m from north to south and enclosed by the walls of the structure, was revealed in this excavation area. The courtyard was built over artificial fills laid to a depth of c. 3 m. Unearthed southwest of the courtyard were parts of three elongated rooms and the foundation of their floors.

Area B was excavated in the north of the site. A wall of the structure, c. 2.8 m wide, and five rooms flanking it were found in this excavation area. One of these rooms was fully excavated, its walls preserved to a height of 1.8 m. Upon its floor were found many crushed storage jars and evidence of an intense fire that destroyed the room. The discovery of the many storage jars suggests that the rooms were used for storage.

Area D marks the southern end of the structure. Found within it was part of a room, including a wall and a brick floor abutting it from the south. The floor was laid upon a foundation of bricks and kurkar, similar to the foundation uncovered in area A.

STRATUM 6. Stratum 6 is represented by alterations, noted in only the southern part of the building (area A). The walls of this phase are thinner than those of the original construction, and the bricks are larger. A long hallway survives, apparently roofed by vaults built of fired bricks, the hallway’s floor made of gray plaster. Few sherds were found on the floor; they place this phase at the end of the seventh century BCE.

STRATUM 5. Stratum 5 is attributed to building activity dated to after the palace was razed. The wall foundations are built of fieldstones and abutted by a tamped earth floor. Remains of the stratum were also found in areas C and D. The walls were not preserved, but were probably built of bricks above the stone foundations. Sherds identified as coming from the seventh century BCE were retrieved on top of the floors.

CONCLUSION. The conquest of Ashdod by the Assyrian king Sargon’s commander-in-chief, Tartan, is mentioned by Isaiah (20:1–6) and Assyrian sources. Assyrian accounts also relate that Ashdod rebelled twice against the Assyrian king. In 711 BCE Sargon marched against Yamani, Ashdod was conquered and annexed by Assyria, and an Assyrian official was appointed to the city. The Assyrian-style palace uncovered in excavations to the north of Tel Ashdod would have been a suitable headquarters for such an official, and potentially an administrative center for all of Philistia in the Iron Age and perhaps through the Persian period.

REMAINS FROM LATER PERIODS

STRATUM 4. Remains of stratum 4, dating to the Persian period, were destroyed by Hellenistic period constructions and are thus scanty and poorly preserved. In area B, Persian finds derived from dump pits only. A segment of a wall foundation built of fieldstones and oriented east–west was found in area C, as was a pit used as either a dump or a repository that yielded fragments of cultic stands and two lekythoi.

STRATUM 3. Stratum 3 consists of Hellenistic period remains, uncovered in the northern area of the site (area B). Found were parts of walls and floors of a structure, two phases of which were distinguished but the plan of which cannot be ascertained. Retrieved on the floors of both phases were coins and many pottery sherds. In addition, a large dump pit of the same period was found to the south of the structure. Uncovered in the western part of the site (area C) were a segment of an east–west wall and a stone-built water channel running east of the wall. The finds included many pottery sherds.

Five furnaces were found in the southern area of the site (area A). They are round and were used for the firing of ceramic vessels. Two were fully excavated, while two were exposed so as to only allow for the ascertaining of their general form and diameter. The rounded roofs of the furnaces were supported by a central pillar or an arch. Such a large number of furnaces in a small area indicates that it was an industrial area for the manufacture of pottery vessels.

STRATA 2–1. A built tomb with an arched ceiling dated to the Late Roman period has been attributed to stratum 2. The tomb had been robbed and was not excavated. Its chronological attribution is based on the fact that it was at a lower elevation than those of the cist graves of stratum 1. These cist graves, four in number, were found on the western edge of the excavation and were apparently part of a large cemetery. They are rectangular, lined with worked kurkar slabs, and sunken into the dunes covering the site. Three contained adults and one a child.

ELENA KOGAN-ZEHAVI

EXCAVATIONS

Subsequent to preparatory work for the laying of railroad tracks for a line between Ashdod and Ashkelon, a salvage excavation was conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority near Tel Ashdod. The first season took place in November 2003–January 2004, under the direction of E. Kogan-Zehavi, and the second in April–June 2004, under the direction of E. Kogan-Zehavi and P. Nahshoni. Other small-scale excavations were conducted by D. Varga in 2003, in an arched tomb from stratum 2, a cist tomb from stratum 7, and a furnace from stratum 3. The excavation area is located some 200 m northwest of Tel Ashdod, and as based on previous knowledge, outside the area of the mound. Four excavation areas (A, B, C, D) were opened during the excavation, yielding archaeological remains from five periods—the Iron Age and the Persian, Hellenistic, Late Roman, and Byzantine periods—described below from the earliest to the latest.

AN ASSYRIAN-STYLE PALACE

The prominent remains from the excavation are basement rooms and a bathing room of an Assyrian-style palace, which once spread over an area of at least 2.5 a.