Ashkelon

THE NEOLITHIC SITE IN THE AFRIDAR NEIGHBORHOOD

THE SITE

The most ancient settlement known in Ashkelon is dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C (first half of the eighth millennium

EXCAVATIONS

The site was first surveyed and excavated in 1955 by J. Perrot, who in 1996 published the results of his research in a final report. He conducted an intensive surface survey and documented the site topography before it was entirely destroyed by development activity. Perrot noted several concentrations of finds over an area of several hundred meters and estimated that the site covered approximately 5 a. In the western part of the site, which was rich in finds, a test excavation was conducted over a c. 100-sq-m area, exposing a dense concentration of pits. These are circular or elliptical in shape. The base diameter of most exceeds that of the mouth, producing a bell shape. The depth of the pits ranges between 1–2 m. No traces of structures, installations or hearths were found during this excavation. The finds included flint and stone tools but no pottery. The area excavated by Perrot was quickly covered by sand.

From 1992, boat docks, hotels, holiday apartments, and a network of surrounding roads have been constructed in the area. Most of the kurkar ridge was removed, and since the precise location of the Neolithic site was not known, large parts of it were entirely destroyed. In the spring of 1997 and winter of 1998, salvage excavations were conducted at the site under the direction of Y. Garfinkel of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. An area of c. 1,000 sq m was examined and c. 800 sq m of the Neolithic settlement was excavated. This area is, in our view, located approximately 20 m east of the area excavated by Perrot. A series of 14C determinations date the site to 8,000–7,600

EXCAVATION RESULTS

In the area examined, the following sequence was obtained (from top to bottom): (1) Approximately 0.5 m of sand and modern debris, including remains of a kiosk that once stood at the site, numerous glass bottles, colored ceramic tile, electrical wires, telephone wires, and sewage pipes. (2) Approximately 1.5 m of yellow sea-sand that included pottery from the Byzantine and Muslim periods (including several glazed sherds). (3) A number of pits filled with yellow sea-sand and Byzantine sherds. (4) Three pits with finds from the beginning of the Early Bronze Age. Along the Ashkelon coast, in the Afridar and Barnea neighborhoods, this settlement extends over several dozens of acres. (5) A Neolithic settlement layer 20 cm thick in its shallowest parts and up to 2 m thick in the deeper areas. This layer has a dark brown hue and is composed of clay and sand with burnt stones, lumps of fired clay, animal bones, and artifacts including worked flints, bone tools, and stone tools. No pottery was found in the excavation. This is clearly a Pre-Pottery site. (6) Virgin soil, consisting of weathered kurkar in the western portion and a brown clay layer in the eastern.

THE SETTLEMENT REMAINS. Features observed in the Neolithic settlement include:

Hearths. Of the approximately 80 hearths found in the excavation area, most were found directly on virgin soil, some within shallow pits. The hearths are round or ovoid and built of medium-sized and small stones, densely arranged. Large orange and black lumps of fired clay were found in some of the hearths. In several cases the edges of the pits took on a reddish-orange hue as a result of burning. The largest concentration of hearths was found in the northern part of the excavation.

Pits. In addition to shallow pits in which hearths were constructed, other pits of various sizes were found in the new excavation area, scattered at considerable distances from one another. Some of the pits are cylindrical while others are bell shaped. The smaller pits may have served for storage while the larger ones could have functioned as dwellings. The dense concentrations of pits encountered by Perrot were not found in the new excavation area.

Living Floors. Surfaces particularly rich in finds occurred upon virgin soil and some 10–20 cm above it. These included enormous quantities of animal bones, including cattle, pig, goat/sheep, gazelle, and fish.

A Wall. In the entire excavation area only one built wall was found: a straight wall extending northwest to southeast for a distance of c. 20 m. The wall is built of two rows of small and medium-sized local kurkar stones. Part of the wall is built of small rounded bricks, made of light-colored clay and not well preserved. The northwestern part of the wall is higher, and only the western row of stones has been preserved. On the lower southeastern part two rows of stones have been preserved.

A Floor. Abutting the wall on the west was found a small, leveled surface of light-colored material that may include some crushed chalk. Upon this surface were various finds: an arrowhead, a denticulate sickle blade, and an obsidian artifact.

THE FAUNAL REMAINS. An outstanding feature is the large amount of animal bones, which constitute the bulk of the finds at the Ashkelon Neolithic site. This has no parallel at Neolithic sites elsewhere in Israel, where the predominant finds are flint tools. The large number of animal bones and hearths here apparently attest to intensive meat processing and preservation activities having taken place at this site. Proximity to the sea provided access to salt, which plays an important role in meat preservation.

THE FLINT AND STONE TOOL INDUSTRY. The flint industry is the major element of material culture at Ashkelon. In terms of technology, it should be noted that this is a flake industry based upon small amorphous cores. There are no flint outcrops on the Coastal Plain. The nearest ones are located in the Shephelah region to the east, over 10 km away. The only available flint on the Coastal Plain is in the form of relatively small pebbles swept downstream by the wadis draining the Judean Hill and Shephelah regions into the Mediterranean. It thus appears that most of the flint-knapping activity that produced the tools found here took place outside the settlement.

The flint tool typology is characteristic of the Neolithic, and includes arrowheads, sickle blades, and a few axes. The most common arrowhead types are medium-sized examples typical of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C. In addition, a few larger arrowheads typical of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and a few particularly small arrowheads typical of the Pottery Neolithic were found. Sickle blades are made on particularly fine, thin, and long blades, many with a working edge consisting of a row of broad, deep denticulation, of a type common at

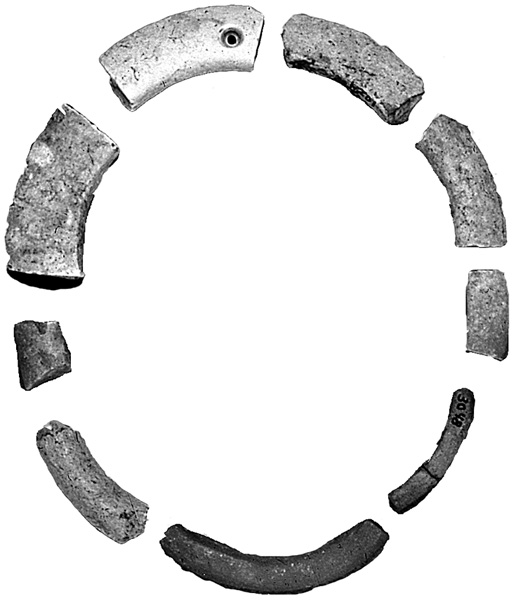

Several stone tools of the following types were also found: small grinding stones, hammerstones, bowls, choppers, and stone rings. All of the stone tools were found broken. These were finds that were discarded after they became unusable. No massive tools for processing plant foods, such as mortars, pestles, and grinding slabs, were found. There were several fragments of white ware vessels, made of burnt lime rather than clay, and several bone tools, obsidian artifacts, and worked shells.

SUMMARY

Perrot defined the area of the Neolithic site at Ashkelon as consisting of c. 5 a. Most of this early settlement was destroyed over the years by development activity. Extensive excavation clarified that this is an outstandingly unique and important archaeological site in Israel in several respects:

- Chronology and material culture. The absence of pottery and the appearance of sickle blades and arrowheads of the types noted above attest to the period referred to as “Pre-Pottery Neolithic C.” This phase is clearly known today from only four sites in Israel: Ashkelon, stratum II at

Tel ‘Ali ,‘Atlit Yam , and recently,Ha-Gosherim . Thus, the site represents one of the least-known periods in the archaeology of Israel. - Economy. The large quantity of animal bones, the hearths and the special knives made on tabular flint are evidence of specialized activity at the site. It served as a butchering site for cutting and preserving meat and appears to have been an early pastoral camp on the Mediterranean coast.

- Geography. On the shoreline of the Coastal Plain, no important Pre-Pottery Neolithic A or B sites have been discovered, while the only two important Pre-Pottery Neolithic C sites have been found and excavated at Ashkelon and

‘Atlit .

YOSEF GARFINKEL, DORON DAG

TEL ASHKELON

EXCAVATIONS

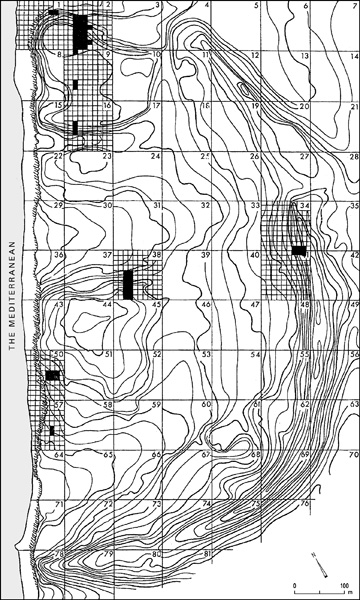

The Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon has conducted excavations at Tel Ashkelon for 17 seasons, from 1985 to 2000 and another in 2004. The expedition is sponsored by the Semitic Museum of Harvard University and co-sponsored by Boston College. The Director of the Expedition is L. E. Stager. The excavated fields discussed here include grid 2 on the north, grid 50 on the seaside, and grid 38 in the center of the mound.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE. Tel Ashkelon was abandoned from the end of the Early Bronze Age III to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age IIA, a period lasting some three centuries (2250–1950 BCE). During this gap in occupation, a small group of agro-pastoralists encamped a couple of kilometers to the north. The Mediterranean shipping lanes, which included Ashkelon, ceased during the Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I in the southern Levant and during the First Intermediate Period in Egypt, when, according to the “Admonitions of Ipuwer”: “None indeed sail north to Byblos today. What shall we do for cedar for our mummies?” No such hiatus seems to have existed during this period in the northern Levant. This continuity of culture in coastal Syria and farther east is of great significance for tracing the origins of “Amorite-Canaanite” culture farther south (Middle Bronze Age IIA), when new urban centers were created throughout Canaan, starting with the Mediterranean Coastal Plain, from Acco to Ashkelon, and spreading inland.

During the Middle Bronze Age IIA, Ashkelon became a bustling seaport once again, the largest in Canaan, with a population of 12,000–15,000 inhabitants living within its ramparts. This arc of freestanding fortifications determined the shape and morphology of the city for the next 3,000 years. Some of these fortifications have been revealed in excavations on the north slope of the tell (grid 2). In addition, excavations uncovered some of Ashkelon’s Middle–Late Bronze Age necropolis (grid 50).

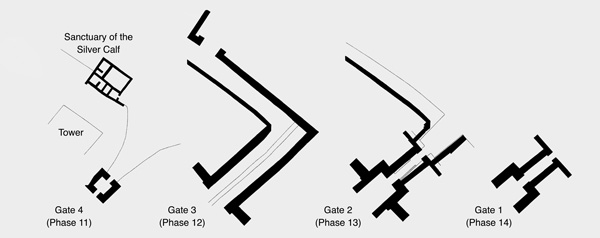

The Northern Gates and Ramparts. In grid 2 on the north slope the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon revealed a sequence of four earthen freestanding ramparts (misnamed “glacis”), all built in the Middle Bronze Age IIA and reused until the end of the Middle Bronze Age IIC (with possible continued use into the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Ages). Three city gates (gates 1–3=phases 14–12, dating from Middle Bronze Age IIA to early IIB) and one “footgate” (gate 4=phase 11, dating from mid to late Middle Bronze Age IIB) were built into the ramparts, which reached a height of c. 15 m (not including the curtain walls and towers which once crowned the crest) and were more than 70 m thick at their base. All phases are local to the grid, with equivalencies to phases between grids indicated whenever possible. Gate 1 (phase 14) had been about the same size and plan as gate 2 (phase 13, see below); the latter was built over the partially buried remains and shaved-down foundations of the original gate. A sandstone causeway led directly into gate 1 from the outside. This land bridge was created when a dry moat was cut into the sandstone bedrock on each side to a depth of 6.00 m and a width at the top of 7.00 m.

Trapped in the debris filling of the earliest moat and sealed by the artificial embankment and roadway of gate 2 were the most important indicators for determining the absolute dating of the Middle Bronze Age IIA in Canaan: more than 40 clay sealings stamped by Egyptian scarabs from the early Thirteenth Dynasty. The local and imported pottery from this context (the moat deposit) compared very favorably with that of Tell ed-Daba‘a/Avaris, later to become the capital of the Hyksos, whose excavator M. Bietak espouses a low absolute chronology for this period, which is also largely compatible with that which W.F. Albright advocated more than 70 years ago, but based on far fewer data.

The similar imports and local wares found at Ashkelon and Avaris have allowed for a comparative stratigraphy chart. Sherds from a classical Kamares ware cup, manufactured in central Crete and exported to the eastern Mediterranean during the Old Palace period (Middle Minoan IIB), were found in the moat deposit. Along with Cretan imports came Cypriot white painted cross-line style jug fragments, pithoi from coastal Syria, and zirs, or water jars, from Egypt. Workshops in Ashkelon and elsewhere in Canaan were manufacturing Tell el-Yahudiyeh ware for export during the Thirteenth Dynasty. Later, during the “Hyksos” (Second Intermediate) period, Tell el-Yahudiyeh ware was being manufactured in Egypt and exported to the Levant. The transport amphora, known as the “Canaanite jar,” was the primary container for shipping wine and olive oil from the Levant to Egypt. It is the most ubiquitous amphora produced in Ashkelon.

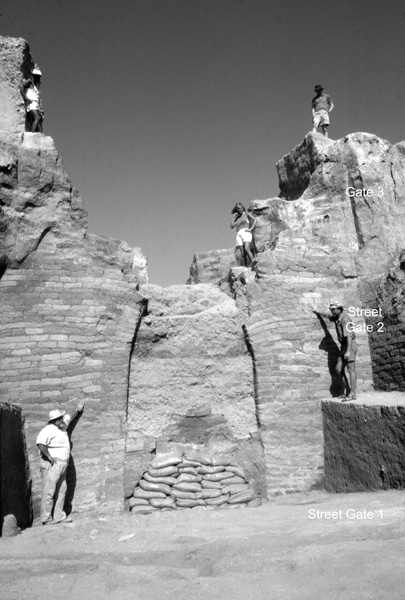

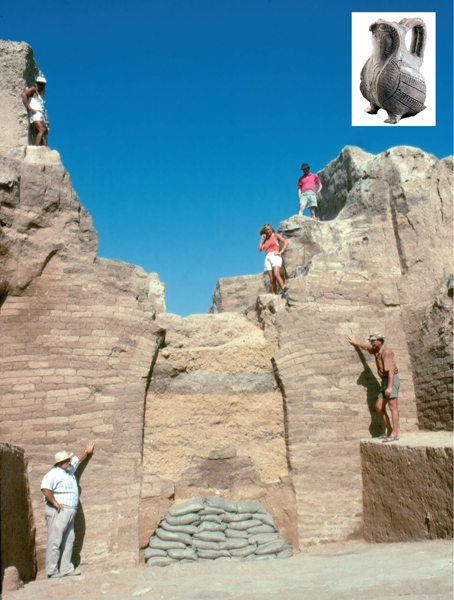

Gate 2 (phase 13) was approximately 27 m long. Its ruins preserve, up to the second story, the oldest known city gate with an entryway spanned by a long barrel vault. It was fortuitously preserved because the builders of the succeeding city gate cut through the ceiling of the first story, laid a large corbelled drain of mud bricks on the ground floor, without dismantling much of the architecture, and then filled the chamber, nearly to the top, with sand and debris.

Gate 2 is also the earliest example of a city gate in Canaan with an indirect approach. A ramped roadway composed of compressed ash led up from the sea, above the filled-in old moat. A new, deep moat was cut and a mud-brick revetment wall was created, behind which the high earthen embankment was renewed three times and covered with three different stone mantles during the lifetime of gate 2. Since the height of the glacis rises at least 4.00 m above the preserved remains of the second story of the gate, at least a third story seems necessary.

Originally a beautiful rabbeted entrance of mud bricks flanked both sides of the outer court in front of the arched entryway. Later the east side of the entrance was replaced with a straight north–south wall, and two huge mud-brick buttresses were built on both sides of the arch, probably to keep the gate from collapsing outward. The sandstone ashlar blocks, three rows deep (1.86 m) on each side of the arch, are quite large, measuring 0.80 by 0.40–50 by 0.25–30 m. The blocks in the jambs and voussoirs are set in alternating headers and stretchers, tightly locked in place. The ashlar façade of the entrance is 7.00 m wide; the doorway of the arch, 2.30 m at the base. The entrance was more than wide enough to admit wheeled vehicles, such as horse-drawn chariots and large carts.

The arched entryway led to a barrel vault (a 9-m-long “tunnel”), which connected to the inner arched doorway, built of mud bricks. Later, the sides of the barrel vault were shored up by stepped mud-brick buttresses on each side, which also acted as curbs. The steep street through the vaulted tunnel was paved with mud bricks.

The inner gateway was built on top of the shaved-down foundations of gate 1. Two massive mud-brick towers (each 2.80 m thick) flanked the arched entryway, 2.45 m wide. Only the apex of the mud-brick arch was missing. Like the stone arch, it was built in bonded style; that is, in alternating courses of headers and stretchers integrated into the whole façade. The Ashkelon arches, then, are quite different from the slightly later (transitional Middle Bronze Age IIA/B) radial arch in the

A 7-m square, framed on three sides by towering mud-brick walls, formed the inner court of gate 2. Mud-brick wing walls projected at right angles from the side walls to anchor rampart fills along the inner slope.

The free-standing rampart, the rabbeted façade, and the bonded arch are all new architectural elements in Middle Bronze Age IIA Canaan. They appear already in the third millennium in the Habur Triangle at Tell Beydar, Tell Chuera and Tell Muazzar, and probably farther south at Terqa and Mari. It seems that with the advance of “Amorite” or “West Semitic” cultures along the Fertile Crescent these several architectural innovations were introduced into Canaan early in the second millennium BCE.

Gate 3 (phase 12, transitional Middle Bronze Age IIA/B) was the largest of the city gates excavated in grid 2, set above the partially preserved remains of the second story of gate 2. Its roadway from the sea passed through a lower gate before following the earlier but steeper path to the city gate. The towers and side walls of gate 3 were so massive that the much smaller footgate (gate 4), which led up from the Sanctuary of the Silver Calf (now dated to the Middle Bronze Age IIB), was carved out of the remains of gate 3. The northern city gate must have been moved farther east, perhaps even as far as the medieval Jaffa Gate.

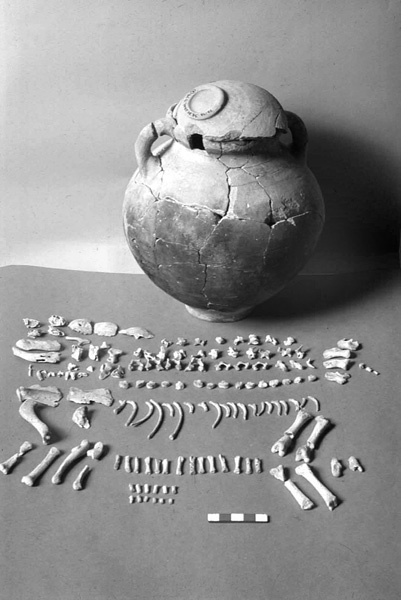

The Necropolis. The city of the dead in grid 50 was carved out of bedrock a few meters below the city of the living. From this complex of burial chambers within the confines of the city, it is hoped to learn something about Canaanite burial practices, to retrieve a demographic profile of the city’s inhabitants, and to infer elements of their kinship system. Physical anthropologist P. Smith has examined the skeletal remains of hundreds of individuals. Using ancient DNA analysis, N. Mekel-Bobrov has been able to test an old but still unproven hypothesis: that Canaanite society was dominated by a patrilineal kinship system.

The necropolis consists of dozens of Middle Bronze Age II–Late Bronze Age II chamber tombs: each tomb complex had a single entrance through a vertical shaft, cut from ground level to the chamber tomb below. The ceilings of some of the tombs had been quarried away by the Iron Age II Philistines prior to the construction of the seventh-century BCE marketplace (see below).

The DNA study has focused on skeletal material from chamber tomb 5, with six niches and repositories carved around the central chamber. The burial goods span a period of five or six generations, beginning c. 1700 BCE. The pottery vessels included amphoras for wine, oil and water, as well as table ware (but rarely cooking pots), including serving bowls with lamb chops as part of the mortuary offerings. Items of personal adornment accompanied many of the burials, such as finger-rings with scarabs set in gold bezels. Canaanite scarabs inscribed with meaningless Egyptian hieroglyphs apparently warded off evil. Only toggle pins remained of the clothing or shrouds in which the dead were buried.

Buried in tomb 5 were at least 62 individuals, of which 40 were adults. Of that number, 22 yielded ancient DNA: 10 males and 12 females. One of our tasks was to determine whether there was any order or pattern to the interments, most of which were disarticulated, or secondary burials, in niches and repositories. N. Mekel-Bobrov has recognized three patrilineages in this tomb, each buried in separate niches or repositories; whereas the females, from five different matrilineages, showed no such locational affinity. From these data it can be concluded that during the Middle Bronze Age II, individuals were buried in this family tomb according to patrilineal descent: the niches and repositories functioned as further partitions of burial according to households and lineages. Marriage was virilocal. Probably descent and property were passed on through the patriline. The tombs of Ashkelon thus illustrate, rather strikingly, aspects of West Semitic-Canaanite-Amorite culture also shared by Israelites. They give concrete meaning to the biblical expressions “to sleep with” and “to be gathered to one’s fathers” (cf. 1 Kg. 11:43; Gen. 49:29).

The well-built central-courtyard house 630 (Mittelsaalhaus) occupied the southern part of grid 50 (phase 10) in the thirteenth century BCE, the latest occupation before settlement resumed there in the latter part of the twelfth century BCE. Five meters north of this substantial building a fragment of a cuneiform tablet was found. Part of the columns written in Sumerian and Canaanite was preserved. J. Huehnergard and W. van Soldt restored the Canaanite column on the basis of similar lexical texts from Ugarit and Emar. According to petrography, the Ashkelon tablet (MC 49535) originated in the vicinity of Tyre and was imported to Ashkelon, to train apprentice scribes there. In this case the students were learning to write phrases concerning parts of the month, the new moon, the new year, and the month of Nisan.

THE LATE BRONZE AGE–IRON AGE TRANSITION. During the final days of courtyard house 630, the last burials were interred in the necropolis below. Some Mycenean IIIB, much Cypriot base-ring and white slip II wares, and a Minoan “oatmeal” flask littered the rooms of the courtyard house. This was the last of the imported pottery from the Aegean world.

A few meters south of grid 50, W. J. Phythian-Adams sank his seaside trench. There he detected a burnt layer that he assumed represented a citywide destruction of the Late Bronze Age (stage VI), before the earliest settlement of the Philistines (stage V). The Leon Levy Expedition has found no evidence of extensive destruction during this changeover. The Egyptian garrison, which dominated the Canaanite city after Merneptah’s campaign, fled their premises as the Philistines took over Ashkelon shortly after 1175 BCE.

Stretching across the excavation trench from balk to balk for 15 m was mud-brick wall 1080 of phase 21 in grid 38. Its foundation was made of bricks, laid on a spread of sand, at exactly 17.50 m above sea level: this in contrast with the mud-brick walls on stone foundations, typical of the Canaanites and the Philistines. Only three courses remained of wall 1080; they were sufficient, however, to ascertain that its builders alternated a course of headers with a course of stretchers. The mud bricks measured 0.54 m long, or one Egyptian royal cubit. The wall was 2.10 m wide, equivalent to four Egyptian royal cubits. A small buttress protruded from the west end, perhaps suggesting that the rest of the compound continued to the north. Parallels to the Egyptian fortresses excavated at

THE IRON AGE I. Phase 20. A new architectural scheme dominated phase 20 in grid 38. At the south end of the trench, remnants of walls with stone foundations (one with fragments of an Egyptian beer bottle lodged between the stones) jutted at right angles from both faces of the three-course-high Egyptian wall, which became either a walkway or revetment between these new constructions. At the north end, three grain silos (perhaps originally belonging to the Egyptian garrison) were filled up with refuse.

Sealed in and under the earliest Philistine plaster floor, which bonded onto the impressive stone wall 985, was local “Canaanite” pottery of the Late Bronze Age tradition (cf.

S. Sherratt and A. A. Bauer commit another kind of fallacy in their bold claim that the influence or presence of eastern Mediterranean merchants, especially Cypriots, can account for nearly all of the cultural variations and innovations introduced at the beginning of the Iron Age from Cilicia in the north to Philistia in the south. This extrapolation is narrowly based on a dubious interpretation primarily of the Mycenean IIIC pottery evidence and fails to take into consideration the many other aspects of material culture, which distinguish Philistia from other parts of the littoral.

One of the most striking differences setting apart Philistine culture from other Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I cultures in Canaan is the remarkable increase of pork in the diet: from just 5 percent in Canaanite Ashkelon and Ekron to almost 20 percent in those two Philistine cities, according to zooarchaeologist B. Hesse. This increase was in line with the high consumption of pig in the Mycenean world, where it averaged c. 30 percent. The exception seems to be Cyprus, where the percentage of pig at 5 percent is closer to that at non-Philistine sites.

Although not a major part of the food resources, the occasional consumption of mature domestic dogs marked a major difference in the Philistine diet at Ashkelon from that of their Near Eastern neighbors. Canid remains in the early Iron Age assemblage showed butchering, skinning, and dismemberment marks similar to those found on sheep and goat bones. Recently, similar canid remains, evidently stewed in Aegean cooking jugs, have been identified at the Iron Age site of Kavousi-Kastro in eastern Crete. Throughout Philistine Ashkelon during the Iron Age I, the predominant and often the only type of loomweight was a non-perforated cylinder of unbaked clay, often slightly pinched in the middle, known as the spoolweight. Hundreds of these have been found at Ashkelon, several were recognized at Ekron, and a few at

| Year | Dynasty | Dab‘a Avaris | Ashkelon Grid 2 | Aphek | Crete | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB IIB | ||||||

| ↑ | D/3 | |||||

| XV | ||||||

| 1650 | ||||||

| 11 | ||||||

| 1675 | E/1 | FOOT | ||||

| E/2 | GATE | MM IIIA | ||||

| 1700 | ||||||

| E/3 | ||||||

| 1725 | Ph. 4 | |||||

| XIII | ||||||

| 1750 | F | 12 | ||||

| GATE 3 | ||||||

| 1775 | G/1–3 | 13 | MM IIB | |||

| GATE 2 | Ph. 3 | MM IIA | ||||

| 1800 | Egyptian Sealings | |||||

| G/4 | ||||||

| 1825 | 14 | |||||

| GATE 1 | ||||||

| 1850 | H | ↓ | Ph. 2 | MM IIA | ||

| XII | ? | |||||

| 1875 | ||||||

| 1900 | ||||||

| Ph. 1 | ||||||

| 1925 | MM IB |

In room 859 to the west carved ivories were found: a duck’s head from a cosmetic box, the capsule of an opium poppy once part of a small scepter, and a beautiful comb with incised chevrons and guilloche pattern on one side and guilloche on the other. Another ivory fragment has part of an incised sacred tree, or palmette, motif. It and other ivories from phase 20 have parallels in

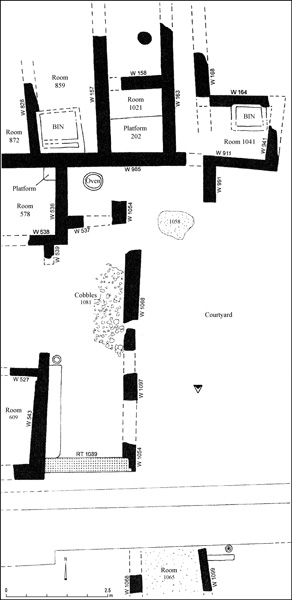

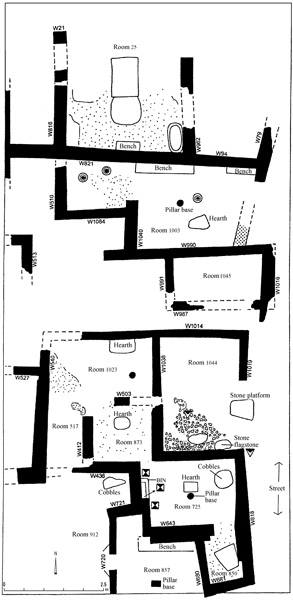

Phase 19. Phase 19 heralds a completely new architectural layout, which features a north–south street and two domestic complexes (dubbed the north and south villas), separated by an irregular open courtyard. This basic scheme will continue after phase 19, which is characterized by a combination of Philistine monochrome (Mycenean IIIC) and bichrome pottery; through phase 18, with only Philistine bichrome pottery; and through phase 17, with late Philistine bichrome and the beginning of red-slipped wares. The new north–south street continued to be built up with multiple resurfacings for the next five centuries. The north end of the north villa broke off at the edge of the mound in grid 38, but not before parts of three large rooms could be salvaged. A large bathroom 25 had two major appointments: a full-size bathtub carved from chalk (no drain) in the southeast corner, and a large keyhole hearth—a platform made of mud bricks—in the middle of the room. Lugs on the bathtub suggest its original use as a larnax. It became a bathtub in phase 19; in phase 18 it was broken up, reassembled, and plastered as a wine vat. The combination hearth and bathtub was also found in

Throughout the early Iron Age I (phases 19–17) a common feature in the main living rooms of the villas was a pillar in the center with a hearth nearby or along the side of the room. The hearths were rectangular, square, circular, U-shaped, and keyhole. They were built with mud bricks and sometimes lined on top with potsherds to retain the heat. At Ashkelon, the Iron Age I architecture and its various features, such as pillars and hearths, have their closest parallels in Cyprus (as at Enkomi).

Another distinctive feature of this early Philistine architecture was the use of Glycymeris mollusk shells, laid open side down and then covered with mud plaster. This combination of shells and plaster sometimes continued up the side of the wall. The shells probably served as a kind of insulation. A similar use of Glycymeris is attested at Tell Kazel, ancient

A foundation feast of some sort must have accompanied the construction of the south villa. Pig bones were scattered in the street to the east. At street level and sealing the foundation trench at the northeast corner of living room 725 was a cairn of stones. Under the stones the head of a donkey (Equus asinus) had been buried. In the nearby courtyard (room 1044) another donkey skull had been marked under a pile of cobbles. Presumably these animals had been sacrificed and eaten as part of the foundation ceremony. Inside room 725, buried under the floor, lay three separate foundation deposits, each consisting of a bowl containing an unused lamp covered by an inverted bowl. Bowl-lamp-bowl deposits, a Canaanite custom, were found in room interiors along the walls in phases 19–17. Just off living room 725 was the small pantry 850, paneled with large mud bricks, which were set on edge, giving them the appearance of “orthostats.” Beneath a collapse of mud bricks a cache of monochrome and bichrome pottery lay on the floor.

In room 1033 of the north villa, three store jars, each cut off above its four handles, were sunk until the widest diameter of the jar was at floor level. The jars were surrounded by a wide brim of Glycymeris shells, open side down. Again, the mollusks were intended to hold heat, although the overall purpose of these installations, which are also found in phases 18–17, is unclear. Perhaps they were potstills for distilling grappa (a form of brandy) from the pomace of grapes used in winemaking. This is probably the alcoholic beverage referred to as

A dozen or more terracotta anthropomorphic figurines—all female—were found in domestic contexts: three in the north villa (phases 18–17); and nine in the south villa (phases 19/18–17). Most were of the enthroned goddess (or “Ashdoda”) type.

Phase 18. Several changes occurred during phase 18, the first when Mycenean IIIC pottery had disappeared and bichrome pottery prevailed. In the north villa the bathroom became a winemaking area. In its main living room 910, with pillar and hearth, two human infants were buried along the east wall under the floor. In the south villa five more infants were buried in pits (one in a small store jar) under floors and next to walls. Intramural jar burials were known in the Middle Bronze Age but this form of infant burial practice had died out among the Canaanites of the Late Bronze Age. The clearest parallels to the Philistine baby burials come from the Aegean, from Late Helladic IIIC Lefkandi in Euboea. There they buried both infants and adults in pits dug through floors inside rooms of domestic houses, next to room walls. Another kind of pot burial in a pit under the floor occurred in the south villa: the nearly complete remains of a puppy, the skeleton bearing no visible cut marks, was interred in a cooking jug covered by a lid made from an inverted bowl.

During the last stage of phase 18, a raised keyhole hearth was built next to a flagstone pavement on which lay two linen pouches, filled with Hacksilber, each pouch weighing c. 55 grams. These were packaged pieces of cut silver, which served as the precursors of coinage.

In the refuse which filled a large pit dug into the courtyard between the north and south villas, parts of a very rare pictorial bichrome krater were retrieved. On one side, a warrior, perhaps carrying a round shield, confronts an angry sea monster. On the opposite side a figure wearing a Philistine feathered headdress sits astride a one-wheeled vehicle, perhaps an abbreviated form of chariot. Although the meaning of the scenes is far from clear, the various motifs seem to be drawn from many parts of the Aegean world, including Cyprus.

In grid 50 only phase 9 dates to Iron Age I. Parts of four buildings were excavated, each yielding Philistine bichrome pottery. Bowl-lamp-bowl deposits, sunken store jars cut off at the shoulders and surrounded by brims of Glycymeris, as well as spoolweights resemble those from grid 38, phase 18. Room 503 in grid 50 contained a couple of chariot fittings: an ivory yoke saddle knob (similar to those displayed on Tutankhamun’s chariots) and a bronze linch-pin in the shape of “Ashdoda,” the enthroned goddess (cf. the Janus-headed linch-pin from

Phase 17. In phase 17 the Philistine painted tradition continues but in a somewhat debased form. Red-slipped, hand-burnished pottery appears for the first time. This phase is roughly equivalent to

This was the largest Iron Age I exposure excavated. In addition to the continuation with some major changes of the north and south villas, across the street another six-room complex, probably also domestic, was unearthed. Weaving was an important craft in all of these houses; spoolweights were found in nearly every room, sometimes lined up in a row next to a wall, where they had fallen from a vertical loom.

The main living room 868 of the north villa had a long bench along two of its walls and a pillar in the center. Rather than a permanent built hearth, there was evidence that portable hearths, which left patches of ash and charcoal, were used. M. Kislev identified lentils as one of the foods cooked in this room.

Sealed in the collapse of mud bricks was an ostracon shaped from a local Philistine vessel. The text consists of nine characters written in red ink, which are related to or derived from Cypro-Minoan script. Cypro-Minoan remains undeciphered, although the signs seem to relate to Linear A and Linear B. This ostracon may be the first document ever discovered of the Old Philistine script and language. A total of 18 Iron Age I storage jars, imported from Cyprus, Phoenician, Dor, as well as another made in Ashkelon, bore Cypro-Minoan signs incised after firing, probably when they arrived from abroad.

THE IRON AGE II. Little was left of the intervening strata between phase 17 and phase 14 (the winery). Remnants of a five-room building, pits, and silos are all that remained of phase 16, probably dating to the ninth century BCE. Even less remained of phase 15; however, one brick-lined silo yielded some Phoenician fine ware of the eighth century BCE. The monumental winery (phase 14, see below), with its deep foundations, was the major reason that the ninth–eighth centuries were so poorly preserved in grid 38.

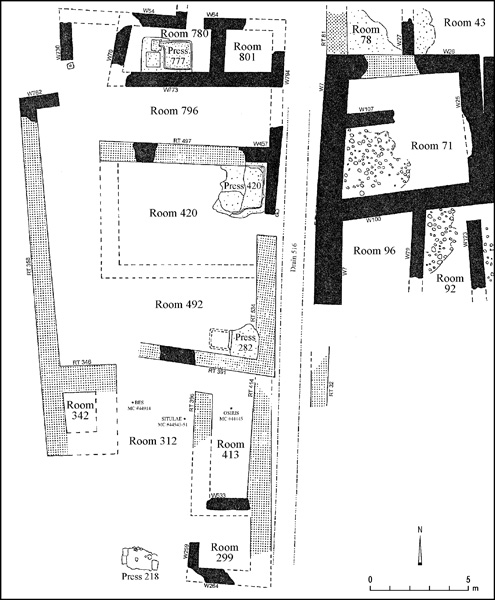

THE SEVENTH CENTURY BCE. Archaeology and texts combine to provide the most precise date known in Philistine history—Kislev (November–December) 604 BCE. At the end of the Iron Age Ashkelon suffered a catastrophic, sudden destruction, evidence for which was found in two distant sites: the winery in grid 38 and the marketplace in grid 50. The destruction was total. In some buildings fires burned so hot that mud bricks, plastered roofs, and ceilings were vitrified. Although many of the finest artifacts were probably looted and carried off by the invaders, ample evidence of the prosperity of Ashkelon on the eve of destruction survives in the form of imported pottery from all over the eastern Mediterranean. In one of the shops of the marketplace lay the skeleton of a 35-year-old woman, flat on her back, her legs akimbo, her skull crushed by a blunt instrument. She was buried under a pile of debris from the fallen walls and ceiling (or roof) of the building in which she had apparently tried to hide. Two hundred meters away in the winery more evidence of the conflagration appeared. In addition to smashed pottery, charred wood, dislodged sandstone ashlars, several items of Egyptian inspiration lay in the ashes: a bronze statuette of the god Osiris, seven bronze situlae, each with a procession of deities cast in relief around the bottle, a miniature bronze votive offering table with a frog and other animals depicted and a faience plaque of the god Bes. It was probably the pro-Egyptian policies of the Philistines of Ashkelon (and Ekron), which led to their demise in the winter of 604 BCE.

In the Babylonian Chronicle Nebuchadnezzar II provides this brief but telling notice about the fate of Ashkelon: “He (Nebuchadnezzar) marched to the city of Ashkelon and captured it in the month of Kislev. He captured its king and plundered it and carried off [spoil from it…]. He turned the city into a mound and heaps of ruins and then in the month of Sebat he marched back to Babylon” (BM21946, 18–20).

The prophet Jeremiah (chapter 47) and the Greek poet Alcaeus (Loeb fr. 48, 11 and cf. fr. 350) also allude to this destruction at the hands of the Babylonian army. Ashkelon was not reoccupied again until late in the sixth century (c. 525 BCE) when the Persians encouraged Phoenicians from Tyre to settle there.

Fortifications. The Philistine fortifi-cations, built sometime around 1000 BCE, still protected Ashkelon when the Babylonian army approached the seaport four centuries later. On the north slope a thick mantle of sand, soil, and other debris was added to the earlier Bronze Age slope, the crest of which was capped with a series of mud-brick towers connected by a curtain wall. The two towers excavated were 8.00 by 10.50 m and spaced 20 m apart. Presumably this series of towers continued around the rest of the fortification line. If so, then as many as 50 towers fortified the seaport on its landward side, just as 53 towers protected the city in the medieval period. This massive fortification system was destroyed in the battle of 604 and not rebuilt until the Hellenistic era.

The Winery. In the center of the city (grid 38, phase 14) stood a monumental building with plastered sun-dried mud-brick walls supported by foundations of sandstone ashlar blocks laid in header-stretcher fashion. It occupied c. 400 sq m west of the north–south street that had been established by the Philistines in the late twelfth century BCE (phase 19). Four winepresses alternating with storage chambers indicate that this building was a winery. Another large building, also used for storage, lay east of the street. The architectural style and prominent location suggest that this was a royal winery, under the supervision of King Aga, the last of the Philistine rulers of Ashkelon.

The winepresses had pressing platforms, vats and basins, lined with cobbles and coated with smooth, waterproof plaster of very high quality. Dipper juglets and fat-bellied storage jars were the predominant pottery types found in the winery. Unbaked clay balls with a single perforation through the center, typically identified as Levantine loomweights in the Iron Age II, probably served, in this context, as stoppers for the wine jars during the fermentation process.

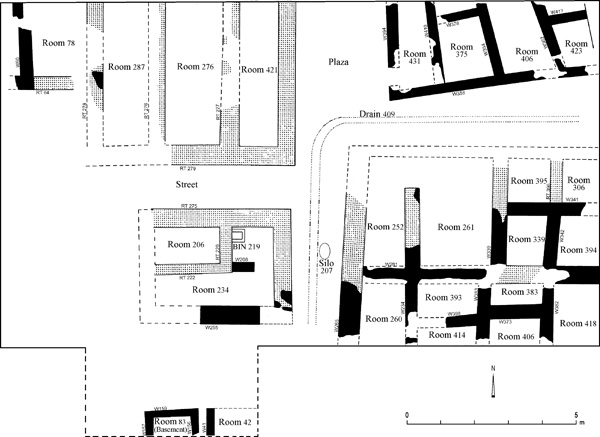

The Marketplace. By the sea, a marketplace or bazaar was excavated over a 500-sq-m area (grid 50, phase 7). Many of the building stones for the marketplace had been quarried from the bedrock below. The builders then filled in the quarry with deposits of sand and other debris, sometimes 2–3 m deep, containing an abundance of pottery, including East Greek types dating to the last quarter of the seventh century BCE. The architectural scheme laid out on top of this massive fill was completely new.

A row of shops flanked the street on one side, an administrative center on the other. The first shop (room 423) was littered with dipper juglets and wine jars. An ostracon inscribed in Phoenician script lay in the street just outside the wine shop. It was a receipt for a consignment of five jars or units of “grappa” (

What Ashkelon lacked in wheatlands to feed its population of 12,000–15,000 or more, it made up in its commercial economy, in which viticulture dominated. Through its export of wine from its vineyards along the coast and its import and reexport of olive oil from the inner Coastal Plain, Ashkelon could purchase rather than produce many of its staples.

Pottery also attests to the prosperity of Ashkelon in the last quarter of the seventh century BCE, when its maritime trade was flourishing. From the quantitative and petrographic analyses by J. D. Schloen and D. Master, respectively, it is known that the vast majority of pottery (77 percent) found in seventh-century BCE Ashkelon was manufactured locally. Not surprisingly, shipping containers known as amphoras constituted half the total of local and imported pottery. Mixing and serving bowls followed with 30 percent; smaller jars, jugs, juglets, bottles, and lamps with 17 percent; and cooking pots with 3 percent. Imported pottery (23 percent) came in order of frequency from the Shephelah (13 percent), Phoenicia (5 percent), the Negev (3 percent), Ionia and the Greek islands (1 percent), Cyprus or North Syria (1 percent), and a lesser amount from Egypt.

Although the Greek component constitutes only 1 percent of the total, it is one of the largest yet excavated in the southern Levant. Fine wines were shipped to Ashkelon in distinctive amphoras from Miletus and the Greek islands of Chios and Lesbos, along with wine pitchers (oinochoai) decorated in Wild Goat style and East Greek mixing bowls (kraters). Elegant East Greek drinking vessels, including bird and rosette bowls, Ionian cups and Milesian wild-goat-style stemmed dishes complete the imported wine service. Perfumed oils arrived in alabastra and aryballoi decorated in Early Corinthian style. In addition, a number of one-handled cooking jugs, with highly micaceous fabric and S-shaped profiles, were imported on the eve of Ashkelon’s destruction in 604 BCE. It seems likely, as J. Waldbaum has concluded, that the Greek cooking pots at Ashkelon represent trade items rather than crockery indicators of the presence of East Greek mercenaries stationed there.

The destruction of Ashkelon (and of Ekron) by the Babylonians in Kislev 604 BCE has provided a chronological anchor-point for reassessing the typological sequence and dating of Phoenician, Neo-Philistine, and Aramaic scripts as well as those of Philistine, East Greek, and Phoenician ceramics.

LAWRENCE E. STAGER

Ostracon

Underwater Surveys

Color Plates

THE NEOLITHIC SITE IN THE AFRIDAR NEIGHBORHOOD

THE SITE

The most ancient settlement known in Ashkelon is dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C (first half of the eighth millennium