Banias

EXCAVATIONS

Since 1988, two archaeological teams have worked separately in the ancient city. The first, headed by Z. Ma‘oz, concentrated on the exposure of the Sanctuary of Pan. This work was terminated in 1994 and the remains exposed were preserved, partly restored, and opened to the public. The second team, under the direction of V. Tzaferis, unearthed large parts of the Roman palace and succeeded in locating the city’s cardo maximus. This work was halted in 2000 and the palace remains are now accessible to visitors via newly constructed paths and staircases.

THE SANCTUARY OF PAN

The rare combination in a single locale of a snow-capped mountain, a forest, a spring, and a cave, each in itself sufficient to constitute a holy place in ancient Greek tradition, led to the foundation of a rural cult-place inside the grotto at Banias. Its earliest use as such is unknown, but it does receive mention as the Paneion as early as 200 BCE by Polybius (Hist. XVI, 18). It may be safely surmised that cultic rites were performed here from the Early Hellenistic period (third century BCE), at which time Palestine was under Egyptian-Ptolemaic rule. Ptolemy II is known to have founded cities in northern Palestine around the year 260 BCE, such as Philadelphia (Rabbath-Ammon) and Ptolemais (Acco), and many sanctuaries to the god Pan were established in Egypt during his reign: in the western desert, along the Nile, and in Alexandria (Strabo, Geog.1, 10). Thus Ptolemy II is a likely founder of the Paneion at Banias. However, as the Ptolemies did not generally construct temples outside the Nile Valley, it remains possible that a rural cult-place at Banias was established only by itinerant soldiers or merchants, who, impressed by the natural setting, began to make private offerings to the god Pan (the guardian of roads, in addition to his famous role as the he-goat shepherd-god). The savage character of the cult of Pan was apparently well suited to the forested environment and the local pastoral population.

The sanctuary of Pan is located in the shade of a long rock scarp (c. 80 m long, running east–west, 30 m high) at the foot of Mount Hermon. According to geologist A. Heimann, the ledge on which the sanctuary was built consists of boulders from the collapse of an extremely large karstic cave, c. 100 by 40 m; the present cliff constitutes the original back wall of the cave. The southern part of the terrace slopes steeply towards the springs, located c. 10 m lower. The springs and river form a natural boundary between the mountainous, forested, savage environment of the Pan sanctuary and the inhabited Roman town built to the south of the water sources. At the left (western) extremity of the rock scarp is the opening of a large natural cave (c. 26 by 30 m, 17 m high).

Josephus (War I, 404) provides a detailed description of the site, leaving no doubt that the present-day cavern is the one he describes. The bottomless pit he mentions is probably a Greek chasma—a mystical, physical connection to the River Styx flowing in the netherworld. In the third century CE, Eusebius (Historia Ecclesia VI.18) describes an annual festival at Paneas, in which animals were cast into the water after their throats had been slit. Those who miraculously resurfaced were considered sacrifices rejected by the demons inhabiting the water (similar rites on the Nile were recorded in the fourth century CE; Vita Pachomius Sbo 4; Shenute, Discourse 4). The appearance of blood in the waters of the Cave of Pam[n]ias was also alluded to by the Jewish sage Yose Bar Kisma in the early second century CE (

A Paneas coin minted under Julia Soemias (222/1 CE) shows the temple of Tyche (location unknown), the Pan Grotto, and a ship with four sailors. Y. Meshorer was puzzled by the appearance of a ship on a coin of a town so far inland. He therefore proposed connecting the Paneas sailors with the legendary argonauts who apparently play a leading role in the legend recorded in P.T. Ter. 8:10, 46b–c. This legend, and probably the coin too, indicate that the notion that the underground river (Styx), which connected all underground seas and springs, flowed under Paneas and connected it with, among other places, Tiberias, was commonly held. All the water-related legends referred to above pointedly aim at emphasizing the centrality of the springs of the cave to the life and cults of the city.

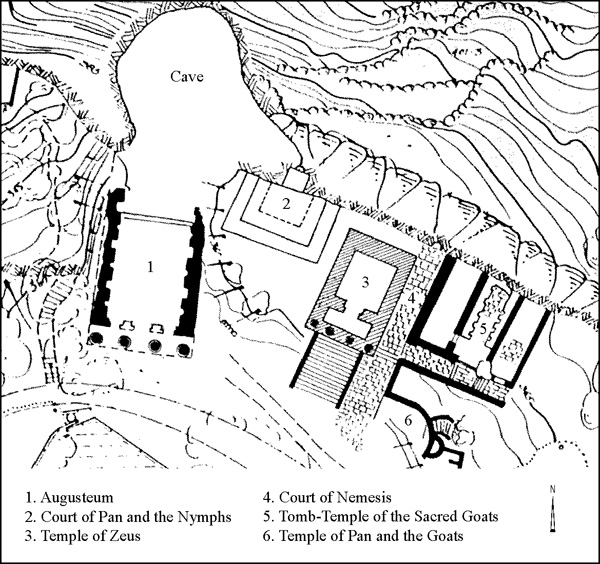

ARCHITECTURE AND FINDS. Along the terrace outside the cave, a series of temples and open-air cult platforms were unearthed, built successively from west to east over a period of some 250 years. Together they constitute the sanctuary, and occupy the entire length of the terrace and the slope down to the springs. The sanctuary area was subsequently occupied in medieval and Ottoman times. Its stratigraphy, as unearthed in the excavations, is as follows:

- Stratum VII: Iron Age and Persian period (eighth–fifth-century BCE) pottery on the slope.

- Stratum VI: The Hellenistic rural cult site; phase VIa: Early Hellenistic period (third century BCE) ramp-wall and pottery on the slope; phase VIb: Late Hellenistic (second century BCE) plastered ramp-wall and slope deposits.

- Stratum V: The Roman and late antique sanctuary; phase Va: Herod the Great and the construction of the Augusteum (Augusteion); phase Vb: construction of the Court of Pan and the Nymphs (first century CE); phase Vc: construction of the Temple of Zeus and Pan (98/99 CE); phase Vd: construction of the Court of Nemesis (178/9 CE); phase Ve: construction of the Goat Temples and streets (Severan period); phase Vf: architectural additions and occupations (Byzantine period; fourth–mid-sixth centuries CE).

- Stratum IV: Squatters refuse pit 243 and signs of a conflagration in the remains of the Augusteum (late sixth century CE).

- Stratum III: Early Islamic industrial structures (ninth–eleventh centuries CE).

- Stratum II: Mameluke domestic suburban structures (twelfth–fourteenth centuries CE).

- Stratum I: Ottoman sheikh’s tomb and surface finds (sixteenth–nineteenth centuries CE).

Stratum VII. No more than a handful of Late Iron Age and Persian period sherds was found among the rock crevices outside the entrance to the cave. The sherds nevertheless are important testimony that the site was visited in the Biblical period and may have even been a venerated spot, reviving late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century CE proposals to identify the temple of Ba‘al-Gad (Jos. 13:5; Jg. 3:3) with Banias. A careful rereading of the sources does not render such ideas absolutely impossible.

Stratum VI. The earliest structures in the series built along the terrace are two parallel walls that supported a Hellenistic ramp leading up to the cave entrance. They may have also served as retaining walls of the road from Damascus to the coast, which bypassed here the springs and the Jordan River. A short section of the earlier of the two walls, constructed of very large stones, was unearthed below the southwestern corner of the Temple of Zeus. In the adjacent soil layer a small third-century BCE assemblage of sherds was collected. According to A. Berlin, this consisted of mostly local ware including fragments of 14 bowls, 21 saucers, and 3 imported black-glazed pieces. Twenty-eight of the 35 locally produced pieces are of a type called spatter ware, which originates in the

The second ramp wall, higher-up on the terrace, was exposed for a length of c. 18 m, its outer side still coated with thick white plaster. It was associated with a deposit of pottery from the second half of the second to the early first centuries BCE, with a considerable amount of imported ware, including 15 sherds of red-glazed Eastern terra sigillata A, black glazed pieces, and a wine jar from Italy. In addition, a large quantity of local pottery was found, mostly jars, juglets, bowls, and cooking pots. This assemblage, according to A. Berlin, attests to the increased importance of the cult-place and its attracting of pilgrims from distant places.

Stratum V. Considerable remains from the Roman through Byzantine periods were unearthed in the sanctuary area.

PHASE Va. The most imposing architectural monument appearing on the coins of Paneas is a semicircular colonnade. However, no remains identifiable as such were found in the excavations outside the cave or on the sanctuary terrace. A possible aid in locating it may be found in the details on the coins and the present-day topography. When the depiction of the colonnade fills the entire face of the coin, the number of columns is 23, 25, or 30. It thus seems fairly certain that the semicircular colonnade had at least 25–30 columns and perhaps many more. As the minimal intercolumniation of such a colonnade is 2.5–3 m, its perimeter would have ranged from 62.5 to 90 m. This was undoubtedly an enormous structure, especially in comparison to other temples on the terrace, whose combined length reaches only c. 75 cm. If positioned in front of and below the sanctuary terrace, such a colonnade would have extended across roughly the entire length of the terrace. However, the space below the terrace is occupied by the springs and a river. In Roman times water was channeled to (and stored in) an artificial pool surrounded by a peristyle, and perhaps this is the semicircular colonnade depicted on the coins.

It is tempting to attribute the construction of such a colonnaded pool to Herod, who in 19 BCE built the first temple at the site, the Augusteum. Such a project would be in character with his other building works. The Jericho, Herodium, and Caesarea palaces all include colonnaded pools. Perhaps the Augustan peristyle pool at the heart of the spring sanctuary at Nîmes (or some unknown example closer to home) inspired the planners of the colonnaded sacred lake at Paneas. This lake would have been an integral part of the sanctuary, in its location adjacent to the entrance of the Pan Grotto and temples. Springs were often considered holy, and sacred lakes were commonplace in sanctuaries in Egypt (e.g., Karnak), and can also be found in the Phoenician (e.g., Amrit, Afqa) and Greek spheres. The sacred lake at Paneas would have been an apt locale for the town’s well-known festival, described by Eusebius (above).

PHASE Vb. Adjoining the Augusteum on the east is an open-air cultic area—the Court of Pan and the Nymphs. First-century CE pottery found on the terrace slope adjacent to the platform (including 75 sherds of imported Eastern terra sigillata A ware, Italian terra sigillata, 50 local and imported pottery lamps, 85 cooking-pots, 25 jars, and a few juglets) indicates that this cultic area continued to be frequented by worshippers from near and far in the first century CE. Similar artificial caves are common in Italy during the first half of the first century CE, suggesting that this complex was possibly built around then, i.e., under Herod Philip or Agrippa I, between 4 BCE and 44 CE.

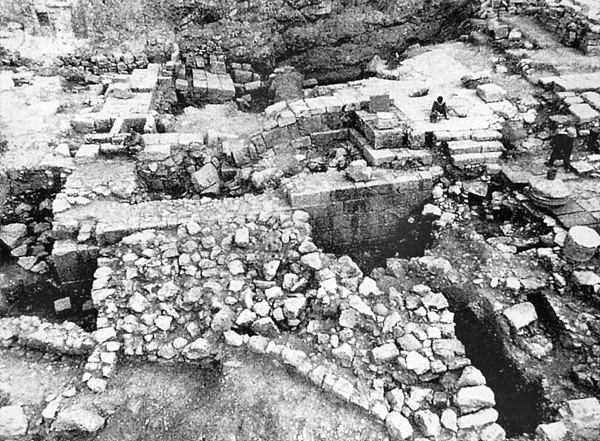

PHASE Vc. This phase consists of the construction of the second temple in the sanctuary—the Temple of Zeus. The structure, of which only foundations were preserved, includes a portico (4.25 m) with four Corinthian columns, and a wide staircase leading up to the temple, which has a broad cella (8.25 by 7.6 m). The exceptionally thick (3 m) back wall may have had an apse and corner staircase towers. Several architectural fragments found either in situ or nearby indicate that the temple had a molded Attic wall-base, Corinthian columns on Attic bases (one example of each was recovered), and pilasters with Corinthian capitals (perhaps only in the corners). The decoration in general finds parallels in the second-century CE temples in Lebanon. The date of construction of the temple excavated here is based on the late first-century pottery found in the portico foundations, a similar Corinthian capital from Palmyra dated 103 CE, and a Greek inscription dating to the reign of Trajan. The inscription was incised on a small broken marble plaque that was found at the northeastern corner of the ruins of the building and read by B. Isaac: “To Heliopolitan Zeus and to the god Pan who brings victory, for the salvation of our lord Trajan Caesar, with his entire house Maronas son of Publius Aristo has dedicated this holy altar.” In addition, an inscribed altar, found in front of the temple, carries the legend IOVI OLYBRAEO, again referring to Jupiter-Zeus. It is tempting to suggest that the Temple of Zeus had been inaugurated on the 100th anniversary of the city of Paneas in 98/9 CE. While the depiction of a temple to Zeus on the coins of Paneas is too schematic to aid in its identification at the site, the number of columns on the depiction—four—matches the excavated building plan, although on the coins a gap was created between the middle columns to show the cult statue inside. There is as yet no evidence from the excavation that can ascertain the form of the (unarched) gable that appears on the coins. In sum, the identification of the excavated temple with that depicted on the coin issue is highly likely but not certain.

The walls and floors of the northeast quadrant of the Temple of Zeus were discovered about 4 m below their original level, having sunken diagonally. According to the horizontal layers above the temple, this occurred between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries CE, perhaps the result of a minor flood or an unrecorded earthquake that caused the remains of the temple to collapse into an underground hollow.

PHASE Vd. The Court of Nemesis is located adjacent to and east of the Temple of Zeus. Relatively few pottery sherds, dated to the second–third centuries CE, were identified in the excavation. They include about 20 platters of Eastern terra sigillata A and 35 local oil lamps. Cooking pots and jars from this period are difficult to recognize because the same forms continue through the fourth century CE. The dearth of ceramic finds has led A. Berlin to suggest that the sanctuary declined in importance and had fewer visitors from abroad in this period. However, the abundant Aphrodisian-style statuary recovered (see below), which according to E. Friedland are mostly dated to the second century CE, and the coins, which according to D. T. Ariel derive from distant rather than local mints, indicate precisely the opposite.

To the second century CE belongs a hoard of fragmented marble statues dumped on the eastern edge of the sanctuary in the Early Islamic period (stratum III), over the ruined Tomb-Temple of the Sacred Goats and the adjacent street (phase Ve, see below). The assemblage includes life-size heads of Zeus/Asclepius, Athena, Aphrodite, Hera, Dionysos, and a headless body of a nymph. A colossal head of Athena/Roma was also found, as were numerous fragments of votive sculptures, including a torso of Hercules, a hand of Pan holding the syrinx, a tree trunk with the syrinx, a cow, an emperor’s miniature portrait (probably Constantine), and a limestone fragment of the Dea Syria flanked by a pair of lions. These statues were placed in the temples and courts of the sanctuary from the first century CE, but mostly in the second through the fourth centuries CE. The life-size statues probably served as “cult statues,” whereas the others were brought as offerings.

PHASES Ve–f. Two unusual temples stand at the eastern end of the sanctuary: an upper temple, near the cliff, and another at a lower level, at the edge of a forest still extant today (the sacredness of the forest in the period in question is inferred from its proximity to the sanctuary). Archaeological and numismatic evidence (see below) indicates that both temples were dedicated to the cult of Pan and the Sacred Goats. The development pattern of the Pan sanctuary and a coin of Julia Maesa (220 CE) found below the floor of the upper temple attest that the two were constructed in the period of the Severan emperors.

The upper building, designated the Tomb-Temple of the Sacred Goats, is a three-room structure (18.9 by 16.3 m) abutting the rock scarp. The central hall (12.5 by 6.8 m) is furnished with two elongated galleries or benches (2 m wide, 0.9 m high), the sides of which are occupied by ten cubic (0.6 sq m) burial niches. Inside were found pottery offerings, mostly restorable (80 cooking pots, 88 cooking bowls, 54 lids, 124 bowls, jugs, basins, 135 oil lamps, and 1,863 saucer-bowls or “Banias bowls”; the only imported sherd was of African red slip ware, dated c. 450–520 CE), glass vessels, and a large number of fourth-century CE coins. Most importantly, the niches also yielded more than 1,200 bones, of which more than 900 were identified as capra, including a he-goat horn. While a definitive study of these bones has not yet been possible, there can be little doubt that the animals buried in this structure were predominantly goats. Cultic offerings were made on the roof in front of a niche carved in the rock scarp. The discovery of goat burials in this temple was not a complete surprise, since the coins of the city show that goats were worshipped in Paneas in connection with the cult of Pan (see below).

The lower building is designated the Temple of Pan and the Goats. The temple extends from west to east and only its northern half, which was dug into the natural slope, has survived. Access must have been from the west, from the north–south street below the Court of Nemesis, but there are no remaining traces of an entrance on this side, leaving open the possibility that it was completely open. The width of the building was approximately 7.5 m and the length of the hall c. 11 m. The northern wall was preserved to a length of 7.5 m and is built of ashlars in a header-and-stretcher fashion (the same masonry as in the Tomb-Temple of the Sacred Goats). To the east of the curving north wall is a large apse, less than half of which has survived, but whose diameter can be estimated to have been c. 7 m. In the center of the apse is a niche facing the hall. The foundation and lower course of approximately half of its circumference are preserved. The width of the niche is c. 1.7 m and its depth, from the front of the apse wall, is 1.25 m. Given these measurements, the niche could have accommodated a life-size or even larger statue. The floor of the hall was paved and the walls revetted in polished stone panels. In front of the niche is a large paving stone with mortises for the hinges of a partition.

Two closets or small rooms are set behind the niche, one on either side. Access to the left one is through an opening in the apse wall. Its space (1.55 by 2.7 m) is almost completely occupied by ashlar steps, ascending to a giant boulder, the function of which, as of the room itself in its original use, remains an enigma. The steps appear to lead to nowhere, unless there was a statue above the top step. The room was found filled with a heap of ash and many offerings, including pottery, glass vessels, and coins, indicating that it later served as a repository. The opening to the room on the right of the niche, presumably symmetrical to that of the left room, was not preserved. Three of the room’s walls and a fine plaster floor survived. The maximum dimensions are 4.15 m northwest–southeast and 2.85 m across, a room of considerable size, albeit of unknown function. The main finds here are fragments of four chancel screens (each c. 1 by 0.6 m) made of thin polished limestone and decorated with perforated designs.

It must be noted that, given the thinness of its walls, especially that of the apse wall (0.35 m), it is highly unlikely that the structure could have been roofed. The apse wall could never have supported a semi-dome 7 m wide, or even a modest flat wooden-beam roof, overlaid with soil. Either the building was open to the sky (the most likely possibility), roofed by leafy tree branches (perhaps periodically replaced), or covered by a velarium—a cloth pulled by ropes, as in Roman theaters. The fact that this structure was likely unroofed points to a function as an open court or an animal pen.

Depicted on a series of coins minted at Paneas in 221/2 CE is a cult place consisting of a fenced-off semicircle, inside which are three goats engaging in two variations of a “goat-dance”—with bodies turned to the center and heads touching or with heads turned outward; and a niche with the statue of Pan playing the flute, depicted above (i.e., behind) the goats. The portrayal of an architectural element above another was commonly employed on coins, wall paintings, and mosaics to suggest that the element was in fact behind the other. The combination of a semicircular apse with a niche behind it is exactly what was found in the Temple of Pan and Goats, allowing it to be identified with the one depicted on the Paneas coins. The chancel screen fragments found in the room behind the niche reinforce this, as the screen may indeed be the very partition depicted on the coins. If this identification is correct, the statue that stood in the niche in the excavated Temple of Pan and the Goats was the prominent sculpture of Pan playing the flute that appears on the coins. Perhaps one of the rooms behind the niche accommodated a band of musicians, whose music roused the (trained?) goats in the apse to perform.

THE END OF THE CULT IN THE SANCTUARY OF PAN. A dispute regarding the history of the sanctuary involves the date of the termination of the cult. According to D. T. Ariel, the latest dated coins of phase Vf are not later than 408 CE. At the first quarter of the fifth century CE, in A. Berlin’s view, worshippers ceased to bring offerings to the temples. However, G. Bijovsky has presented a strong case that fourth- and early fifth-century coins remained in circulation through the entire fifth and until the middle of the sixth century CE. In addition, two more coins of emperors Anastasius (498–518 CE) and Justinian (546–567 CE) were retrieved from non-stratified contexts at both extremes of the sanctuary, but nevertheless associated with the temples. The sherd of African red slip ware (c. 450–520 CE) found in one of the niches of the Tomb-Temple of the Sacred Goats should also be taken into consideration. What is certain is that the architectural fragments found in the Augusteum bear evidence of a conflagration that attests to the violent end met by the building. The combined evidence suggests continued activity in the sanctuary, albeit on a much more limited scale, through the middle of the sixth century CE, at which point parts of the sanctuary were burned down, probably by Christians.

ZVI URI MA‘OZ

THE TOWN CENTER

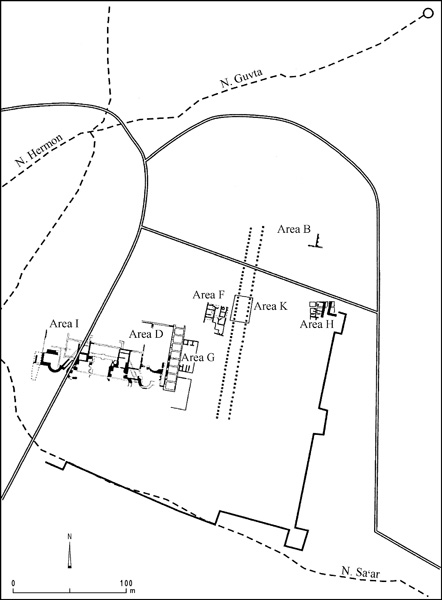

The Joint Expedition Excavations at Banias, directed by V. Tzaferis, continued from 1988 to 2000. In all, ten excavation areas (A–L) were opened to the southwest of the sanctuary of Pan and the springs, each producing rich architectural remains from nearly all of the site’s historical periods. The stratification of the architectural remains in all the areas may be summarized as follows:

- Strata I–II: Early Roman period (first–second centuries CE).

- Stratum III: Late Roman period (third–fourth centuries CE).

- Stratum IV: Byzantine period (late fourth–fifth centuries CE).

- Stratum V: Late Islamic period (eleventh–twelfth centuries CE).

- Stratum VI: Crusader period (twelfth century CE).

- Stratum VII: Ayyubid/Mameluke period (thirteenth–fifteenth centuries CE).

The eight excavation seasons from 1992–2000 were witness to the discovery of the town cardo and of an elaborate Early Roman palace later converted for use as a bathhouse.

THE CARDO (strata I–II). The remains of a colonnaded street with two parallel rows of column bases were uncovered in area K. These lay beneath major structures and installations dated to the Crusader, Mameluke, and modern periods. Though only a small section of the street was uncovered, it seems probable that the street extended the entire length of the civic center, from the ravine in the south (

All seven of the column bases exposed in the western row are monolithic limestone modules consisting of a double spiral Attic-type base, 1.10 m in diameter, with the attached lower part of a column, 0.80 m in diameter, together reaching a total height of about 0.50 m. The bases stand on rectangular plinths, c. 0.40 m high and set on a continuous stylobate constructed of large blocks of yellowish travertine. The blocks rest upon a sort of podium of grayish limestone headers. The entire height of the podium and plinth is about 0.80 m. None of the pavement of the central thoroughfare of the street remains in situ, making it impossible to calculate the exact height at which the top of the stylobate would have stood above that pavement. But judging from what has been preserved, the pavement probably lay at least 0.80 m below the top of the stylobate.

The columns on both the western and eastern rows are spaced at 3-m intervals, the standard intercolumniation in nearly all colonnaded streets excavated in Roman Palestine. Close to the western line of columns were found four nearly complete segments of decorated architraves and several rectangular basalt slabs, probably paving stones from the street. Similar slabs were found in abundance in secondary use in the courtyard of a Mameluke structure located in area B. The finds from the eastern colonnade are less impressive, yet clearly indicative of the colonnaded street. The eastern and western colonnades are c. 10 m apart, indicating the original width of the central thoroughfare. The sidewalks and shops flanking the main thoroughfare were not found in area K.

THE PALACE (strata I–II). The architectural remains discovered in areas D and I and attributed to strata I–II (Roman period) are undoubtedly the most impressive discovered so far at Banias. They belong to a very large and complex structure occupying the southwestern part of the site.

The excavated portions of areas D and I (explored mainly from 1994–2000) together comprise over 4,000 sq m. Several parts of the building still lie under modern roads or medieval structures, while others are covered by the dense and luxuriant vegetation of the park. Not all of the accessible portions of the building have been excavated or thoroughly surveyed; these include the entire northern section of the building, the central chambers, and most of the northwestern parts. The eastern enclosure walls are covered by the massive structure of the medieval citadel.

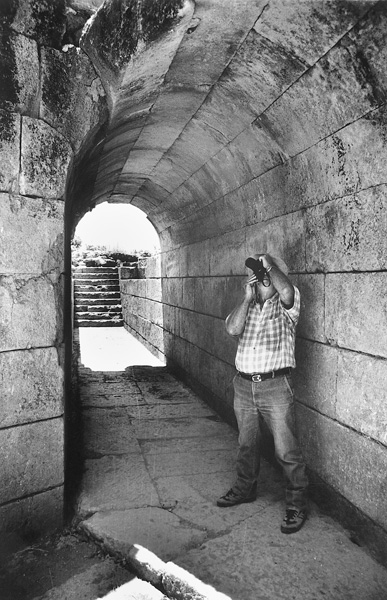

The original structure probably covered an area of c. 10,000 sq m, the entire western section of the civic center of Roman Banias (Caesarea Philippi). Its excavated parts include a spacious civil basilica, halls and rooms, courtyards, and a very complicated system of vaulted passages connecting the various compounds of the structure. In addition, it possessed a sophisticated network of aqueducts to supply fresh water directly from the springs, as well as drains directed to the slopes of

THE BATHHOUSE (strata III–IV). The precise date of when the palace was converted into a bathhouse is unknown. The ceramic and numismatic evidence, provided by very few uncontaminated loci, places the period of the bathhouse’s use within the second–fifth centuries CE, its second-century construction date indicated by the earliest pottery and coins found in these loci. This conversion would likely have occurred in the second half of that century, in which case the palace structure lay unused for a lengthy period, over half a century after the death of Agrippa II. While the general plan of the bathhouse and the specific function of its different parts cannot be determined with certainty, the location of the heated rooms (caldaria) could be detected by the scattered remnants of the hypocausts.

THE VAULTS (strata II–III). The row of 12 vaults (I–XII) found in area C occupies the central part of the archaeological park at Banias and is the first feature noticed by modern visitors approaching the site from the west. Three distinct types of vaults have been discerned: (1) vaults V–VIII are built of large, well-cut travertine blocks with a barrel-shaped roof, typical of Roman arches; (2) vaults I–II are constructed of large blocks in their lower portions and small rectangular stones in their upper, with a pointed-arch roof, typical of medieval arches; (3) vaults XI–XII are constructed entirely of small stones, with pointed roofs. Four vaults (I–III and XII) had collapsed roofs and blocked entrances, two (IV–V) had partially damaged roofs, and the others are well preserved. Each vault cleared during the excavations has a window, 1.20 by 1.00 m, in the rear wall just below the roof.

The understanding that the Roman-type vaults were associated and used simultaneously with the adjacent parts of the palace is based on the fact that the vaults and adjacent parts of the palace share the same floor level, a similar construction technique, and similar building materials; and the vaults are an integral part of the palace structure. Apparently they opened toward the palace through the eastern aisle of the basilica and the openings on both sides of court 3.

THE “BURNT STREET” (stratum IV). A portion of a street dating from the fourth and fifth centuries CE was found in area F, with a series of buildings along each of its sides. The entire complex is located between the palace-bathhouse on the west and the cardo on the east, and lies directly under the northern wall and main entrance of the medieval citadel.

The street, about 3.50 m wide, is aligned north–south. To the south it disappears under the medieval citadel but originally continued to

As a result of a major fire, the four shops along the western side of the street were no longer in use by the second half of the fifth century CE. The same may be true of the structures on the eastern side. In one of the shops, crushed storage jars, jugs, juglets, bowls, glass vessels, various tools (including copper scales), and numerous coins, all of which are characteristic of the fourth and early fifth centuries CE, were found in situ beneath a thick layer of dense ash. It is not possible to establish if these remains indicate a localized conflagration or were the result of a much larger disaster that struck Banias during the fifth century CE.

VASSILIOS TZAFERIS

THE AQUEDUCT

The city of Paneas-Caesarea Philippi was founded at Banias in 2/1 BCE by Philip, the son of Herod the Great, near an abundant spring, the second largest in Israel. The spring supplied water to the city’s houses. Remains of channels and ceramic pipes that belonged to the water supply and sewage systems have been uncovered in almost every spot where excavations have been conducted in the city.

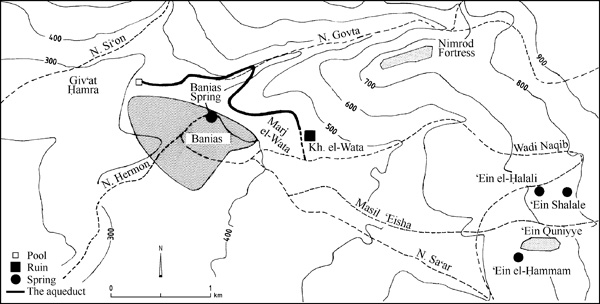

During the second half of the first and the second centuries CE, the city underwent expansion and two new suburbs were built on hills high above and to the east and northwest of the spring. The spacious houses, erected by wealthy residents, required running water, but their elevated position did not allow for the conveying of water from the spring. To rectify this situation, an approximately 4-km-long aqueduct was built to bring water from the east, probably from the springs of ‘Ein Quniyye. The aqueduct was discovered in 1983 during a survey of Banias and investigated from 1983 to 1991. Its western section was excavated by M. Hartal within the framework of the Banias excavation project of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1992–1994.

COURSE OF THE AQUEDUCT. The beginning of the aqueduct has not survived, but it can be assumed that it lay at Masil ‘Eisha, which drains the springs of ‘Ein Quniyye east of Banias. The aqueduct’s course consists of three distinct segments:

- From Marj el-Wata, where its first traces were discovered, the aqueduct passes along a spur that descends from Nimrod Fortress to Banias. One side of the aqueduct was cut in the rock and the other side built above a retaining wall. The spur ends in the southwest in a steep cliff, at the foot of which is the spring of Banias and a large cave. The aqueduct had to pass above this cliff and, because of the very slight difference in height between the edge of the valley and the top of the cliff, the builders had to maintain a moderate gradient here. Installations were built at this point to carry water down to the eastern suburb (the houses of which are as of yet unexcavated) and for the irrigation of the valley. They include a chute for conveying water down from the aqueduct, ceramic pipes, and a large storage pool with pipes branching out from it.

- After crossing the tops of the cliffs, the aqueduct continued down to the bed of

Naḥal Govta. Along this segment the channel of the aqueduct was cut into rock and covered with stone slabs. A number of sharply dropping segments were necessary to overcome the descent to the stream, whereas the gradient along most of the aqueduct’s course was moderate. This part of the aqueduct, located far from the city, includes no distribution arrangements. It crossed the stream by means of a bridge some 7 m high. - After

Naḥal Govta, the aqueduct runs on a moderate decline, underground, to its termination at the edge of the city. Its walls are stone-built, plastered and covered with stone slabs. The aqueduct does not enter the city itself, but extends along an elevated course, parallel to the northwestern suburb, and contains distribution installations along the length of this segment.

THE CHANNEL. The channel is 36 cm wide and c. 50 cm deep, and is built of fieldstone bonded with gray cement, the walls and floor coated with gray plaster with an incised herringbone pattern. It was covered with stone slabs consisting of local stone in the sections far from the city and of reused ashlars closer to the city.

THE SETTLING POOLS. At irregular intervals along the aqueduct are pools that reduced water flow and allowed sediments to settle. They are identical in plan along the entire course of the aqueduct. They have rounded corners and their floors are lower than the floor of the channel. The pools are plastered in a manner similar to the aqueduct channel. In places where the aqueduct was far below ground, shafts were added above the settling pools to allow entry for maintenance work.

THE DISTRIBUTION POOLS. The aqueduct was constructed parallel to the city—never entering it—and at a considerably higher elevation. Installations for distributing water to the city were found along its course. The typical distribution installation includes a small pool alongside the aqueduct, fed by a short channel or ceramic pipe. From the pool, the water entered one or two ceramic pipes that carried it to the houses. Unlike the settling pools, which are similar in plan, no two distribution pools are alike, and they were apparently constructed at different times.

Three of the distribution pools have a more complicated arrangement for receiving water from the aqueduct. Holes were pierced in the walls of the pools and lead pipes were inserted into them: in one pool the holes were square shaped on the outside and the lead pipes were inserted only on the inside, in the other two pools, and in a stone from another pool not found in situ, the holes and lead pipes were conical. Vitruvius and Frontinus give detailed descriptions of elements of Rome’s water system known as calices—conical pipes installed in the outer wall of the castellum, a water tower—to which lead pipes that distributed water to the houses were attached. The calices served as water regulators, their diameters determining the amount of water supplied. To prevent any tampering with the size of the pipes, they were made of solid bronze and under government supervision.

There are two main differences between the pipes of the Banias aqueduct and the Roman calyx: the Banias pipes are of lead rather than bronze and emptied water into the distribution pools rather than from them. Nevertheless, they should probably be identified as calices, as they are similar in shape and were installed for the same purpose of regulating the amount of water distributed to the houses. These are the only calices discovered in aqueducts in Israel and are among the few examples found in the Roman world.

CERAMIC PIPES. Numerous ceramic pipes were used in the aqueduct. These pipes consist of 35–50-cm sections with an internal diameter of 10–12 cm. One end was slightly wider than the other, allowing them to be joined together; their joints were sealed with plaster. According to Vitruvius, such joints were sealed with quicklime mixed with fat. The pipes consist of straight sections only; when a change in course was necessitated, angles were created at the joints. The pipes were laid underground, having been covered with ash and small stones. They carried water from the distribution pools to the houses, a distance of 100–200 m. Filters were set in the mouths of most of the pipes. The filters consist of intersecting iron rods embedded before firing into the sides of the first segment of the pipe. No filters of this type have been found in any other aqueduct in Israel.

In the first half of the third century, the aqueduct became partially blocked with clay deposits. Ceramic bypass pipes were then laid parallel to the blocked portions of the line.

THE OUTLET. The aqueduct terminated near the western end of the city, where it reached a shallow pool, larger than the other distribution pools. This pool was replastered several times. The two outlet pipes of the pool had an internal diameter of 21 cm and were later replaced by smaller pipes of a standard 10–12 cm diameter. The pipes brought water to the houses at the western edge of the suburb.

CHRONOLOGY. Recent excavations have disclosed that the northwestern suburb was built in the first century CE. Because the aqueduct was the sole source of water in this area, it was probably constructed in the second half of that century. Repairs and changes were made in the first half of the third century. In the segments where the aqueduct had a steep descent, the plaster had been damaged, then repaired with a double-layer plaster of red on gray. In the western part of the aqueduct, which was partly blocked with clay, this type of plaster was not found. The latest pottery found in the clay fill within the aqueduct is from the third century. A coin of Banias from 211 CE, discovered beneath the upper layer of plaster in the westernmost pool, provides the date of its latest repairs. The aqueduct apparently continued to function until the fifth century. In the second half of that century, the city underwent a major crisis, the cause of which is unknown, and was greatly reduced in size. At that time, the northwestern suburb was abandoned and the aqueduct went out of use.

MOSHE HARTAL

EXCAVATIONS

Since 1988, two archaeological teams have worked separately in the ancient city. The first, headed by Z. Ma‘oz, concentrated on the exposure of the Sanctuary of Pan. This work was terminated in 1994 and the remains exposed were preserved, partly restored, and opened to the public. The second team, under the direction of V. Tzaferis, unearthed large parts of the Roman palace and succeeded in locating the city’s cardo maximus. This work was halted in 2000 and the palace remains are now accessible to visitors via newly constructed paths and staircases.

THE SANCTUARY OF PAN

The rare combination in a single locale of a snow-capped mountain, a forest, a spring, and a cave, each in itself sufficient to constitute a holy place in ancient Greek tradition, led to the foundation of a rural cult-place inside the grotto at Banias. Its earliest use as such is unknown, but it does receive mention as the Paneion as early as 200 BCE by Polybius (Hist. XVI, 18). It may be safely surmised that cultic rites were performed here from the Early Hellenistic period (third century BCE), at which time Palestine was under Egyptian-Ptolemaic rule. Ptolemy II is known to have founded cities in northern Palestine around the year 260 BCE, such as Philadelphia (Rabbath-Ammon) and Ptolemais (Acco), and many sanctuaries to the god Pan were established in Egypt during his reign: in the western desert, along the Nile, and in Alexandria (Strabo, Geog.1, 10). Thus Ptolemy II is a likely founder of the Paneion at Banias. However, as the Ptolemies did not generally construct temples outside the Nile Valley, it remains possible that a rural cult-place at Banias was established only by itinerant soldiers or merchants, who, impressed by the natural setting, began to make private offerings to the god Pan (the guardian of roads, in addition to his famous role as the he-goat shepherd-god). The savage character of the cult of Pan was apparently well suited to the forested environment and the local pastoral population.