Beth Guvrin

EXCAVATIONS

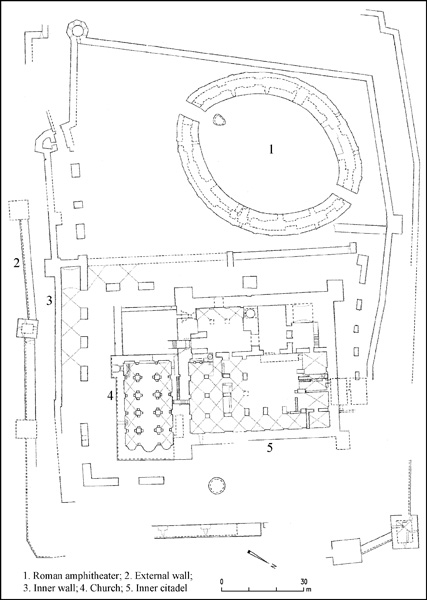

The Roman amphitheater at Beth Guvrin was first identified in 1981 during the archaeological-architectural survey of the city. Probes were sunk during three brief seasons from 1982 to 1986. Systematic test excavations, accompanied by clearance of deposits from the arena, took place from 1990 to 1992. Large-scale excavations were conducted from 1993 to 1995 under the direction of A. Kloner and A. Hubsch. The inner citadel was excavated from 1992 to 1993 by A. Kloner and E. Assaf. The bathhouse located in the citadel enclosure east of the amphitheater was excavated from 1995 to 1997 under the direction of A. Kloner and M. Cohen. The fortress and fortifications have been excavated and exposed since 1992. The church was sporadically excavated in 1982, 1986, 1992, and 1994–1996 by A. Kloner, D. Chen, D. Gamil, and M. Cohen.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

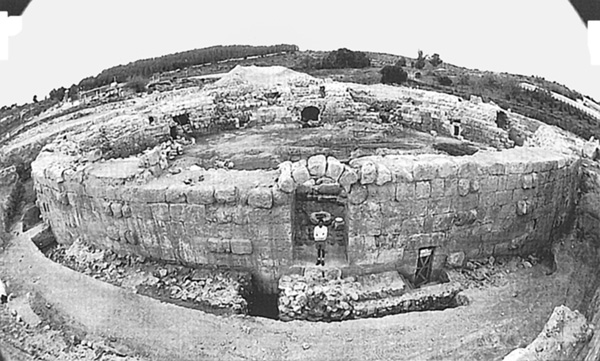

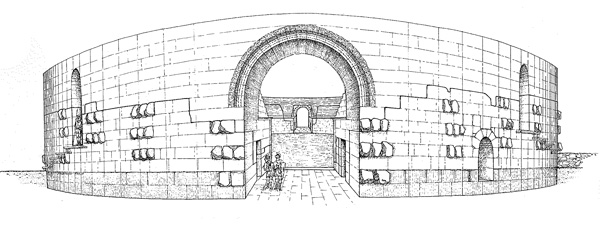

THE ROMAN AMPHITHEATER. The amphitheater was constructed in a previously uninhabited flat area of alluvial soil, northwest of the city. The oval structure’s maximal measurements are 71 by 56 m. Its total area is 3,000 sq m. The building material consists of large rectangular ashlars of locally quarried limestone. The structure includes an arena with subterranean galleries, surrounded by a wall and a relatively small cavea resting upon a series of interconnected barrel vaults that create a large service corridor, also termed ambulacrum or gallery. The corridor is cut at both ends of the central axis (north–south) by two large access galleries leading to the arena. Ten rectangular openings lead from the service corridor to the arena, three vaulted entrances lead from the service corridor to the outside, and two low entrances connect the service corridor to the tribunes, located at both ends of the arena’s secondary axis (east–west). Four vaulted vomitoria led the spectators to and from the cavea.

The arena was the site of gladiatorial contests (munera), animal hunting displays (venationes), contests between men and beasts (bestiarii), and other forms of entertainment. In addition, it apparently served as a place for military exercises and as a parade ground. The amphitheater was built after 135 CE and was utilized as such for c. 250 years. Its use probably ceased following the earthquake of 363 CE. Architectural changes attributed to the Byzantine period attest to the structure having been adapted for use then as a public building of some other sort. The dismantling of the stone seats of the cavea apparently began during the Byzantine period and was completed during the Early Islamic period (seventh–eighth centuries CE). During the medieval and the Ottoman periods the structure served as a stable and contained industrial installations.

The Façade. The outer façade was constructed of opus quadratum. The outer wall of the amphitheater (1.8–2 m thick) is well preserved. Today, seven to nine courses are visible and attain a height of c. 5.4 m on the eastern side. The amphitheater was dry-built on both the outer and inner faces. Small stone chips, probably by-products of stonecutting during construction, were used to level some of the lower courses.

In the outer wall of the amphitheater, an unusual feature is the large, smoothed limestone protrusions projecting from the wall’s surface. Arranged in groups of two or three at c. 4-m intervals with asymmetrical spacing, these may have been placed to facilitate planned additions, but are more likely stylistic elements, intended to break the monotony of the wall surface. No clear evidence concerning the nature of the area outside the amphitheater was found. In the immediate vicinity there were probably streets leading to the building.

The Arena. During the excavation, the arena was entirely cleared of earth up to the assumed original floor level. The floor is presumed to have been of tamped earth laid upon brownish-red soil that was exposed in several places c. 0.3 m beneath the assumed original floor level. A subterranean complex beneath the floor is oriented to the central axes of the arena.

The maximal length of the arena is 56 m and its maximal width 41 m. The wall surrounding the arena (2.3 m thick, 3.9 m high) was constructed of six courses of large, rectangular limestone blocks and covered with painted plaster, some fragments of which remained, in shades of reddish-brown with beige stripes. At the top of the wall was a carved cornice.

In the northwestern corner of the arena, 3.3 m from the surrounding wall, a limestone column was found in situ. Next to it were square and rectangular limestone floor slabs. Eleven similar columns were found in the southeastern part of the arena over the course of several excavation seasons. The columns all stood 3.3 m from the arena wall at 3.3 m intervals and were 1.7 m high and 0.48 m in diameter. The columns and pavement are dated to the Byzantine period and appear to have encompassed the arena, indicating adaptation of the amphitheater in a later phase to a new public function, probably a municipal market with a roofed galley. The depiction of Eleutheropolis in the Medeba mosaic map, dated to the sixth century CE, shows a round structure with a dome and columns. This would appear to be a representation of the amphitheater converted into a public structure with a roofed colonnade during the Byzantine period.

Two large gates at the ends of the central axis lead into the arena. Entrances on both sides of each of these main gates provided access to the service corridor beneath the cavea. Each gate had double wooden doors that opened inward, through which the inaugural procession (pompa) entered the arena. The southern entrance served as the main entrance to the arena, the porta triumphalis facing the city. The northern entrance was probably the porta libitinesis, via which the bodies of the killed gladiators were removed. This entrance was flanked by two rooms, probably spoliaria, to which the injured or killed gladiators were brought.

The subterranean structure of the arena consists of two long vaulted galleries located along the primary and secondary axes of the amphitheater. A length of 31 m of the original 42 m of the gallery along the main north–south axis was cleared. The gallery along the secondary axis is 39 m long. The galleries have vertical openings leading to the arena. Originally, there were eight such openings, two in each of the four arms of the underground galleries. The underground gallery along the secondary axis is connected to a small temple (sacellum) beneath the western tribune. The eastern gallery along the secondary axis has a dead end and no connection with the room beneath the eastern tribune. The southern end of the gallery along the north–south axis is blocked by a stone wall.

Over 650 bronze coins were found in the central portion of the underground complex. These were in poor states of preservation, apparently due to flooding of the subterranean structures. The coins have been dated to the latter part of the fourth century CE. Most were found above floor level. It is suggested that the large number of coins in the fill represents the final period of the amphitheater’s use, toward the end of the fourth century CE.

The Cavea. The small size of the cavea, 7.5 m wide, is one of the main features of the Beth Guvrin amphitheater. Only sparse remains of seats were found, next to remains of later structures built directly upon the vaults supporting the cavea. Four vaulted entrances for the audience (vomitoria) lead into the cavea. Three of the entrances were entirely uncovered; the fourth, in the northern façade, was not excavated. The public entered the cavea from its bottommost level, unlike most known amphitheaters and theaters, where the vomitoria led the audiences to the uppermost level. Two tribunes (pulvinaria) with seats of honor at either side of the secondary axis interrupt the sequence of the cavea. The cavea probably consisted of a single block of seats (maenianum). Given the poor state of preservation of the cavea and the robbing of the rows of seats, it is difficult to accurately evaluate the total number of seats. There appear to have been seven or eight rows of seats in the eastern part of the cavea and it may be assumed that there were originally three or four additional rows. The length of the stone mass that supported the seats is c. 0.65 m, its width 0.60 m, and its height 0.45 m.

The tribunes (pulvinaria) were relatively small and had a limited capacity. Access to the eastern tribune was via a vaulted entrance. Access to the western tribune was via a raised external entrance, c. 2 m above the presumed street level and reached via a wooden ramp or stairs. There was no direct link between the western tribune and the sacellum beneath it, though there is evidence for such a link from amphitheaters elsewhere. The western was the most important tribune, as it faces east and afforded those seated therein a view of the city and its other public buildings, such as the large imperial bathhouse, located below the citadel of the Early Islamic and medieval periods.

The Sacellum. The vaulted room (3.8 by 3.2 m) excavated beneath the western tribune is identified as the amphitheater’s sacellum. In the small cell beneath it were found two Roman cultic altars together with some 100 complete oil lamps and fragments of roughly another 100, providing an indication of the cultic function of the room above. A rectangular niche (1.2 by 0.68 by 0.5 m) that apparently held a statue was constructed in the western wall of the room. The walls of the sacellum were covered with layers of beige plaster, evidence of its importance. There was an entrance from the cultic room to the arena and two entrances to the service corridor. The western tribune above the sacellum indicates that the entrance to it was for gladiators and those with a religious role in the contests.

The Service Corridor. The vaulted service corridor was excavated to its original floor level, with the exception of a small area in the northern part of the building in which a Mameluke furnace was found. The corridor was built of 5.5–6-m segments, as may be discerned from the small angles in the construction of its walls and rounded vaults. This segmented method of construction made it possible for several teams of builders to work simultaneously.

Access to the arena was via ten entrances located in the wall surrounding the arena, each 1.58 m high, 0.95 m wide, and 2.3 m long. Three vaulted entrances lead outside of the building and two low rectangular entrances connect the service corridor with the tribunes. The service corridor was partly illuminated by six rectangular windows in the outer wall of the amphitheater.

The Historical Context. The Roman army was stationed in and around the city following the suppression of the Second Jewish Revolt in 132–135 CE. The construction of the amphitheater stemmed from the presence of these Roman army units in the area and the rebuilding of the city. It is possible that the amphitheater was essentially a military structure serving these units of the Roman Legion. The impressive imperial bathhouse from the same period was uncovered east of the amphitheater, beneath the citadel of the Early Islamic period and the Middle Ages. Construction of the amphitheater and other public buildings is evidence for the rapid urbanization and Romanization of the region during the second half of the second century CE, prior to Septimius Severus’ granting of rights to the city and its name change to Eleutheropolis in 200 CE.

THE BATHHOUSE. The bathhouse was constructed during the Late Roman period, in the third century CE, and remained in use through the Byzantine period. It ceased to be used at the beginning of the seventh century CE. Belonging to the imperial type, it is symmetrical in plan, laid out along a central axis with a central caldarium and open courtyards. It appears to have covered an area of over 4,000 sq m. Only its western portion has been entirely excavated. It sits upon a hillside facing northwest, and in order to level the area, a network of five barrel vaults was constructed, serving as the foundation of the building. These are carefully executed of building stones with marginal drafting (Severan masonry).

The vaulted entrances as well as the passageways between them were each surmounted by a double arch (one riding upon the other). Thirteen such double arches survive from the original building. The double arches were constructed in different sizes and places and some were plastered. Up to now, only two examples of the use of the double arch technique are known in Roman Palestine: in the partition walls of the Struthion tower below the Sisters of Zion Monastery in Jerusalem, and next to the scaenae of the Roman theater at Beth-Shean (second century CE). Several similar double arches are known in Gerasa.

The hot area, located in the western portion of the bathhouse, included hot rooms (caldaria), a tepid room (tepidarium), sweating rooms (sudatoria), a room for anointing with oil or massages, and a hot bath or baths. In each of the rooms exposed in the hot area are remains of a hypocaust. The colonnettes of the hypocaust are covered with ceramic tiles. On some of the walls, the remains of the plaster bear the imprints of the pipes that circulated hot air (tubuli). At the center of the hot area is the main hot room. Two adjacent passages connect the main hot room to the side hot rooms. Every passage consists of two spaces roofed with a half dome connected by a narrow passageway. West of these passages are two spaces that were roofed with vaults. On the wall of the northernmost, impressions on tubuli were left in the plaster up to the tops of the wall; and the conduit into which the tubuli vented was preserved.

At the two ends of the hot area are sweating rooms. The northernmost was entirely excavated and two furnaces (fornaces) were found built into the external walls of the furnace room (praefurnium). The walls of the room are lined with ceramic tiles that protected the stone walls against the heat. The tepidarium is next to the hot room. Between them are two broad passageways that appear to have been blocked. Two additional rooms at the two ends of the bathhouse extend eastward. These rooms were indirectly heated by passages from the hot rooms and probably served as anointing or massage rooms.

To the east is the cold area. Only a portion of its western side was excavated. The frigidarium, pool, toilets, courtyard, drainage channels, and probably dressing rooms were uncovered. The northern part of the frigidarium was constructed upon a system of vaults and includes mosaic pavements and cold pools. At the center of the cold area is a courtyard paved with stone slabs, beneath which passes the central drainage channel. Most of the remains in this area belong to Byzantine period repairs.

The central drainage channel passed under the bathhouse and formed part of the city’s drainage network. Over 50 m have so far been exposed under the bathhouse. It drained into

A latrine was uncovered in the northeastern part of the excavation area. A staircase descends to it. Along the walls runs a 60-cm-wide and 2.5-m-deep drainage channel, which drains into the central channel described above. It was covered by stone seats that were placed into recesses in the walls of the room and rest upon a low wall built along the drainage channel. The southwestern corner of the latrine contains a basin of water that fed a channel of clean water running along the seats. A white mosaic pavement was found along the channels.

THE CRUSADER FORTRESS. The Crusader fortress covers an area exceeding 7 a. and includes three bands of defense: an inner wall, an external wall, and a moat. At the center of the fortress, on the remains of an older citadel, the Crusaders erected an inner citadel and an adjacent church. The fortress was built in two stages, each of distinct construction.

The First Phase. During the first phase, the area of the fortress was 170 by 125 m. Earlier remains had been adapted and reused as building material. Gaps between the robbed building stones of these remains were filled with white plaster, which was incised with herringbone patterns. Primary construction—including gates, entranceways, and pilasters—is of chalky limestone masonry, rather than local nari, and bears the characteristic diagonal stonecutting of the Crusader period and some mason marks. To the north and west, the fortification reused Roman and Byzantine period towers, while to the south and east, new walls were constructed, some of them resting upon earlier foundations. The width of the walls and the towers is 2–2.5 m. In the southwestern corner, the wall meets an octagonal corner tower containing remains of a gate opening to the courtyard of the fortress. The gate remains include a hinge socket for the door and a track for lowering a portcullis. Another gate is located at the northern edge of the north–south wall running across the fortress area.

The inner fortress was utilized in the day-to-day life of the Hospitaller knights and as a final defensive position while under siege. The fortress has four corner towers and was constructed over an Umayyad structure, probably also a fortress. The staircase in the southwestern tower has only been partially preserved. At the center of the inner fortress is a bailey surrounded by a network of cross vaults, which served as dwellings and storehouses. There was probably a second story above the vaults. Beneath the central courtyard is a staircase providing access to subterranean vaults that remained from the Roman bathhouse and were utilized for storage. In the western part of the inner fortress, a large industrial area including warehouses, pools, basins, and ovens was uncovered. The kitchen that served the inhabitants of the fortress was also probably here. In the southern part of this area are two passageways from the Roman-Byzantine period leading to areas used by the Crusaders as reservoirs. Another gate in the eastern wall of the citadel provides access to the well east of it (Bir el-Qela). In the southeastern part of the fortress was found a large hall identified as the refectory. Its entrances lay on the western and northern sides.

The Second Phase. The next phase was probably constructed several years later, after the Crusaders had become firmly established. During this phase an outer defensive system was built that included walls and an external moat surrounding the entire fortress. The area of the fortress was expanded to approximately 190 by 150 m, excluding the moat. During this phase the fortress probably contained a civilian settlement. Unlike the first Crusader phase, the second is characterized by planning and careful execution. The walls, of carefully trimmed masonry, slant inward from the moat as they rise upward, ranging in width from 2–4 m. The towers in the outer wall alternate with those of the inner wall.

The moat to the south of the fortress, in which the modern road between Qiryat Gat and Beth-Shemesh passes today, was a dry moat. In the north,

The tower at the center of the southern outer wall is well preserved. It has two stories, with an inner staircase. On the ground floor are two posterns to the moat. The tower protrudes from the line of the wall, allowing it to defend the moat and the wall via loopholes on three sides. Two other towers, spaced 8 m apart, were uncovered at the northeastern corner of the fortress. One of the entrances to the fortress appears to have been between these two towers. The northernmost was a corner tower, 11 by 11 m, of which only the two bottom courses have been preserved. On its two outer sides are loopholes 1 m above the floor, separated by a raised step to permit quick and safe movement between them. On the northwestern side of the tower is a postern leading from the fortress to

THE CHURCH. Construction of the elaborate Romanesque-style church within the fortress may be dated to the fortress’ second phase. The church was built against the southern wall of the inner fortress. In order to construct the church’s northern aisle, the southeastern tower of the fortress was destroyed. The church rests upon earlier foundation walls, which in effect dictated its dimensions. Its total area is c. 800 sq m and it undoubtedly served a large population inhabiting the fortress and the surrounding area. It was constructed as a basilica, divided by two rows of pilasters into a nave with two aisles that end at the eastern side in three apses. Each aisle includes five bays roofed with cross vaults. The dimensions of the foundations of each pilaster are 3 by 3 m. In constructing the foundations of the pilasters, the builders descended to a depth of 6.5 m beneath the surface, destroying earlier remains in the process. The entrance to the church, contrary to the standard plan, is on the southern side, since the massive wall from the previous Crusader phase rose on the western side. The nave of the church was probably 10 m high while the aisles were 8 m high. In the northern wall was found a passage from the church into the citadel, which could be closed from the citadel.

The decoration of the church consists primarily of architectural elements in secondary use: Roman-Byzantine pedestals, columns, and capitals. The only decorated elements executed by Crusader artists were the beams resting upon the capitals and a number of pedestals imitating Byzantine ones. Sixty-one distinct mason marks were found on the stones of the church, indicating perhaps the number of artisans who took part in the construction. The laying of the stone paving may be dated based upon coins of King Amalricus (1162–1174) found beneath them.

Further additions dating to the Crusader period were found in the fortress. In the area between the inner Crusader walls and the inner citadel (particularly in the northern part of the fortress) were found remains of buildings and installations reflecting the daily life of its inhabitants, such as workshops, warehouses, and stables. It is possible that these buildings also served as dwellings, and they probably belong to the settlement that came about as a result of improved security following the Crusader conquest of Ashkelon in 1153. The surge in building may also have been due to the arrival of 32 Frankish families around 1168, some of whom may have settled inside the fortress itself.

The Date of the Church. The church was constructed after the fortress was already standing, but not before 1140. The disuse of part of the fortifications while the church was under construction, noted in other parts of the fortress as well, did not begin before the mid-twelfth century CE. The floor of the church is dated to the 1160s. Accordingly, completion of the church probably occurred only in the second half of the twelfth century.

Later Phases of the Church Building. During the Ayyubid or Mameluke period, the nave and the southern aisle were destroyed and the northern aisle was closed by massive walls that incorporated the pilasters of the church. These walls were carefully constructed of stones in secondary use laid upon arches relieving the weight of the walls on the pilaster bases. This new arrangement turned the northern aisle into a part of the fortifications of the inner citadel. A prayer niche facing south (

AMOS KLONER

Color Plates

EXCAVATIONS

The Roman amphitheater at Beth Guvrin was first identified in 1981 during the archaeological-architectural survey of the city. Probes were sunk during three brief seasons from 1982 to 1986. Systematic test excavations, accompanied by clearance of deposits from the arena, took place from 1990 to 1992. Large-scale excavations were conducted from 1993 to 1995 under the direction of A. Kloner and A. Hubsch. The inner citadel was excavated from 1992 to 1993 by A. Kloner and E. Assaf. The bathhouse located in the citadel enclosure east of the amphitheater was excavated from 1995 to 1997 under the direction of A. Kloner and M. Cohen. The fortress and fortifications have been excavated and exposed since 1992. The church was sporadically excavated in 1982, 1986, 1992, and 1994–1996 by A. Kloner, D. Chen, D. Gamil, and M. Cohen.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE ROMAN AMPHITHEATER. The amphitheater was constructed in a previously uninhabited flat area of alluvial soil, northwest of the city. The oval structure’s maximal measurements are 71 by 56 m. Its total area is 3,000 sq m. The building material consists of large rectangular ashlars of locally quarried limestone. The structure includes an arena with subterranean galleries, surrounded by a wall and a relatively small cavea resting upon a series of interconnected barrel vaults that create a large service corridor, also termed ambulacrum or gallery. The corridor is cut at both ends of the central axis (north–south) by two large access galleries leading to the arena. Ten rectangular openings lead from the service corridor to the arena, three vaulted entrances lead from the service corridor to the outside, and two low entrances connect the service corridor to the tribunes, located at both ends of the arena’s secondary axis (east–west). Four vaulted vomitoria led the spectators to and from the cavea.