Beth-Shean

TEL BETH-SHEAN

INTRODUCTION

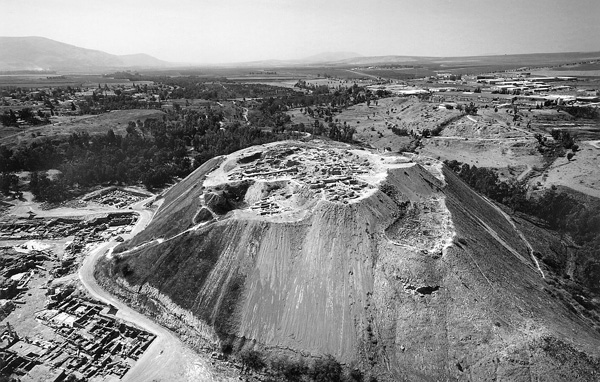

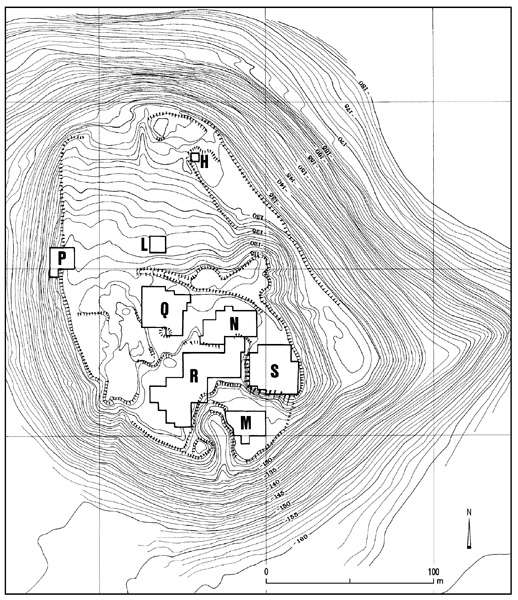

Nine excavation seasons were conducted at Tel Beth-Shean by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem from 1989 to 1996, under the direction of A. Mazar. One major conclusion of the new excavations is that a topographic step crossing the c. 10-a. mound north of the summit, located at its southeastern corner (between the new excavation areas Q and L), was in fact the northern edge of the settlement during most of the Bronze and Iron Ages, except during the Early Bronze Age I, when settlement perhaps spread over the lower part of the mound, remains of which were found in area L. Thus, through most of the Bronze and Iron Ages the settlement at Beth-Shean probably did not exceed c. 4 a. It has been suggested by B. Arubas that the mound was cut to some extent on the south and west during large-scale earthmoving operations during the Early Roman period, when the civil center of Nysa-Scythopolis was constructed; this might explain the lack of fortifications and the fact that buildings in all periods were found cut on the southern and western parts of the mound.

The adjacent chart presents the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania Expedition (UME) strata and local stratigraphy in the Hebrew University (HU) excavations at Tel Bet-Shean.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

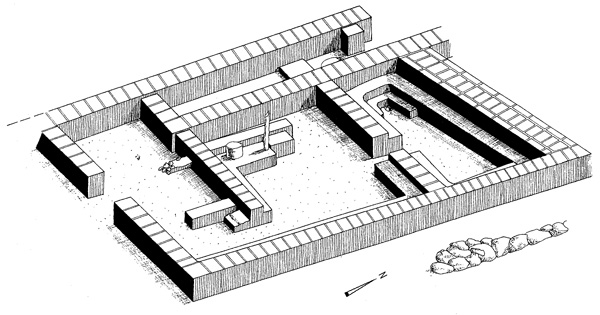

THE EARLY BRONZE AGE I. Area M of the new excavations is located on the southeastern edge of the mound, the highest point of the mound in that period. In this area the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania excavations stopped at the top of level XIV of the Early Bronze Age I. The new excavations revealed there two strata of the Early Bronze Age IB: local strata M3 and M2. A large public building stood there in stratum M3, destroyed and rebuilt in stratum M2.

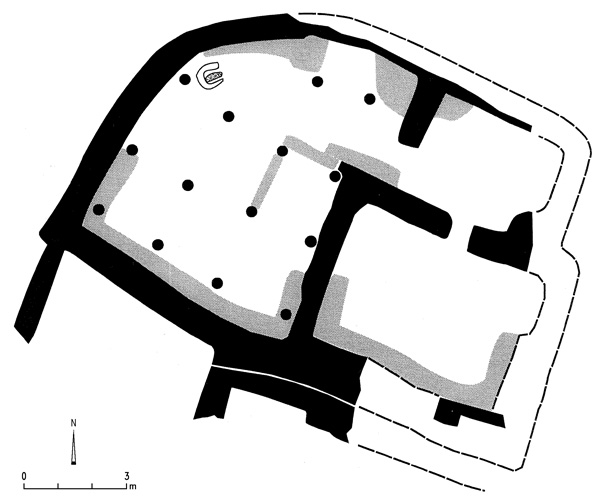

The mud-brick building of stratum M3 includes two rooms on the eastern side and a large hall on the western. Its northwestern wall is rounded. A street runs along the sides of the building on the west and north. The main entrance to the building was not found, but its location could only have been on the eastern side. Benches along the walls and round corner platforms are located in all the rooms. The main hall, 52 sq m in area, has 14 pillar bases made of unworked stone arranged in four rows. An unusual grinding installation was located in the hall, constructed as a raised oval platform. This main hall may have had a second story. The thick destruction layer of this building contained a large quantity of carbonized grain and lentils, and fragments of many band-slipped pithoi and hole-mouth jars. Gray burnished ware is lacking, while it existed in the previous Early Bronze Age IA. The building may be defined as a public one, probably associated with local economic administration. The main hall and its supposed upper story could have been utilized for food storage and processing, while the eastern rooms could have been an official wing for receptions, administration, etc.

| Period | Date | UME | HU: Areas R and S | HU: Other Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medieval | level Ia | P1 | ||

| Islamic | level Ib | P2, L1, H1 | ||

| Byzantine | level II | P3, H2, L2 | ||

| Roman | level III | P4 | ||

| Hellenistic | level III | P5 | ||

| Iron Age IIB | late 8th century | P6 | ||

| Iron Age IIB | 8th century until 732 | level IV and parts of level V | destruction P7: dwelling |

|

| Iron Age IIB | late 9th–early 8th century | parts of level V (?) | P8a–b | |

| Iron Age IIA | mid-10th to 9th century | parts of level V | destruction S1 S1b |

P9; N1 P10 |

| Iron Age IB | 11th century | temples of level V and structures of late level VI (?) | destruction S2 |

N2 |

| Iron Age IA | 12th century (20th Dynasty) | level VI late level VII |

destruction S3 S4 |

Q1, N3a N3b |

| LB IIB | 13th century | level VII level VIII |

S5 | Q2, N4 Q3 |

| LB IIA | 14th century | level IX | destruction R1a |

|

| LB IB | late 15th century | R1b | ||

| LB IA–B | 15th century | R2 | ||

| MB II | 16th century | level XA | R3 | |

| MB II | late 17th century | level XB | R4 | |

| MB II | late 18th/17th century | level XB/XI | R5 | |

| Gap | ||||

| Intermediate Bronze Age (MB I or EB IV) | 23rd–21st century | level XI (mixed) | R6 | |

| EB III | 27th–24th century | levels XI (part)–XIII | R 11–7 | M1 |

| EB II | 30th–28th century | few sherds | R12 (borders EB III) | few remains |

| EB IB | 33rd–31st century | XIII XIV |

M2a–b M3 |

Following the destruction, the building was rebuilt in stratum M2 along the same outlines but with a new inner plan. The large hall was divided by a wall into two rooms and the eastern wing was redesigned. This later building, dated to the end of the Early Bronze Age I, was mostly excavated by the University Museum expedition as their level XIV.

THE EARLY BRONZE AGE II–III. The Early Bronze Age II is represented in area M by only a few sherds, including two with the typical red-painted triangles filled with dots. These sherds could not be associated with any architectural remains. The Early Bronze Age III is represented in stratum M1, which parallels level XIII of the previous excavations. Remains of buildings, streets, and installations excavated by the University Museum expedition were cleaned and several newly excavated loci contained Khirbet Kerak ware and other local Early Bronze Age III pottery.

In the northeastern part of area R, Early Bronze Age III deposits covering an area of about 25 sq m were excavated. Six stratigraphic phases were defined (R12–R7). Phase R12 ended with destruction. A pottery group from this phase appears to be borderline Early Bronze Age II and III. Phases R11–R7 are successive slight changes to a street and fragmentary buildings on both its sides. All these phases included 40–60 percent Khirbet Kerak pottery, the rest local Early Bronze Age III forms, mainly jars. Petrographic study has shown that the Khirbet Kerak pottery was made locally. Beth-Shean and nearby Tel

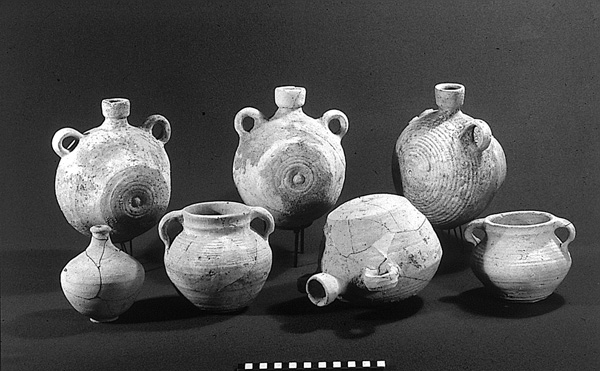

THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (= Intermediate Bronze Age = Early Bronze Age IV). Phase R6 in area R represents a poor settlement from the Intermediate Bronze Age, on top of the last Early Bronze Age III occupation debris. Remains of a floor and few meager walls were found that could have been foundations for tents or huts. Several complete pottery vessels and few copper objects were found. These remains indicate a short-lived, perhaps seasonal settlement. The pottery is similar to that found in the northern cemetery.

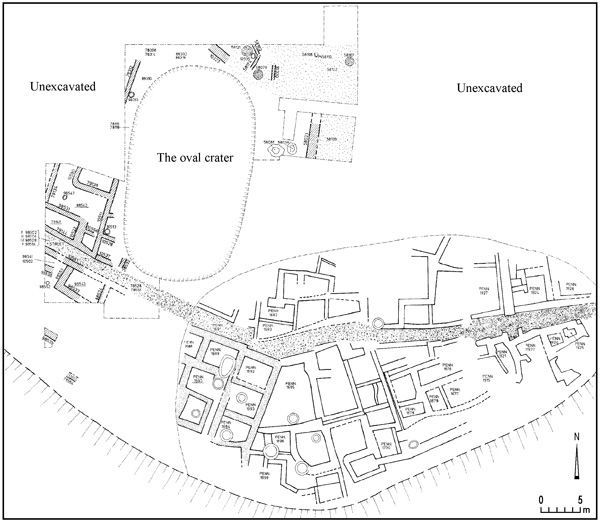

THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE II. There was an occupation gap at Tel Beth-Shean following the Intermediate Bronze Age and lasting until the late Middle Bronze Age IIB, when a well-planned small town (about c. 4 a.) was founded on the summit of the hill. A large part of this town was excavated in area R, extending the area exposed by the University Museum expedition (levels XI–X). The combined plans of the two excavations allow a reconstruction of a considerable part of the town plan. It had a peripheral street parallel to the edge of the mound with houses on both sides, and some elaborate large buildings. No fortifications were found; they either did not exist or were entirely eroded or cut away during the Roman period.

In the western part of area R, three strata were identified (R5–R3), parallel to levels XI, XB, and XA of the previous excavations. Parts of the street and the residential quarter, which continue the University Museum excavation area, were exposed. Infant burials in jars were common in all three strata. In the earliest stratum, elaborate jewelry, alabaster vessels, and pottery dating to the transition between the Middle Bronze Age IIB and IIC was associated with a pit burial of a teenage individual in contracted position. The central part of area R consisted of an 18-m-long and c. 2–3-m-deep oval depression or crater, a kind of huge pit which was filled with layers of refuse thrown into it from all sides. The original function of this pit is unknown. It was filled during strata R5-4 and went out of use in stratum R3, when installations were constructed above it. In the eastern part of area R additional building remains of this period were found. The main feature here is a large open area paved with a thick lime floor on which several hearths and other installations were found. This could be a courtyard of strata R5-4 related to a public building (temple?) located outside the limit of the excavation area. The pottery of strata R5-3 can be defined as belonging to the late Middle Bronze Age IIB and mainly Middle Bronze Age IIC (= Middle Bronze Age III). Imported pottery is rare; it includes few Tell el-Yahudiyeh and Cypriot sherds. Chocolate-on-white ware started to appear in stratum R4 and became popular in stratum R3.

In area M, two pit burials were found dug into the Early Bronze Age levels. They contained few human remains and several complete Middle Bronze Age pottery vessels. Similar pit burials were excavated in the same area by the University Museum expedition. Few remains of Middle Bronze Age burials were found in area L as well, below a Byzantine level and on top of an Early Bronze Age I occupation layer. This area appears to have been outside and close to the edge of the built-up perimeter of the Middle Bronze Age town.

The Middle Bronze Age II town appears to have been a rather small, unfortified town that stood between c. 1700 and 1550 BCE. The circumstances of its end remain unclear. There is no evidence for a conflagration.

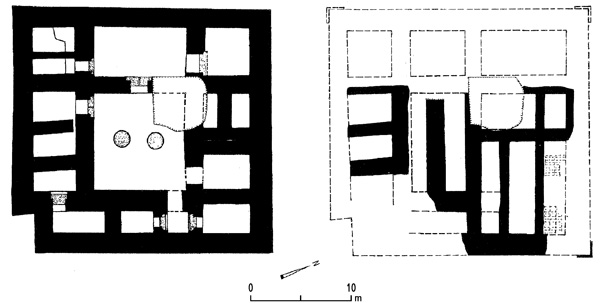

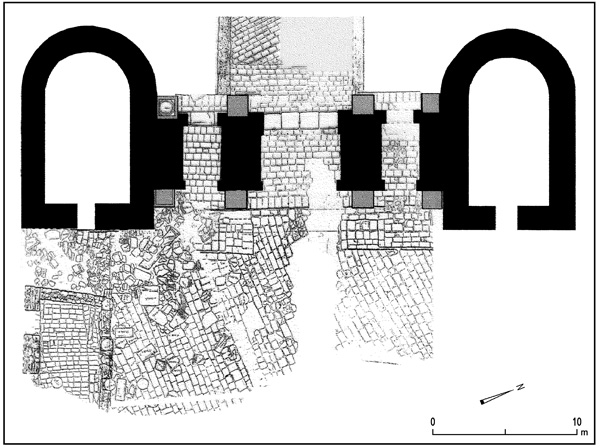

THE LATE BRONZE AGE I: STRATUM R2. Stratum R2 was discerned in a limited area in the central part of area R. In other parts of area R, this stratum remains elusive and indeed is not mentioned by the University Museum expedition. It is therefore interpreted as a local phase between the last Middle Bronze Age II town and the level IX sanctuary found in the previous excavations. A temple and a few additional rooms and installations to its north and south are attributed to this phase. The temple was exposed directly below the courtyard of the University Museum expedition level IX sanctuary and above installations of stratum R3. It is the earliest in the series of Late Bronze Age–Iron Age I temples (levels IX–V) uncovered in the same location by the University Museum expedition.

The temple plan is exceptional: it has an entrance hall on the southern side (internal dimensions 9 by 3.4 m), a main hall, and an inner room. Access to the main hall (internal dimensions 7.35 by 5.6 m) was via a corner entranceway from the entrance hall. Plastered benches are built around its walls; in the western part of the hall is a freestanding bench that widens to form a small platform. A cylindrical stone found standing on this platform may be interpreted as a baetyl; a small post hole on the same platform may indicate the location of a wooden pillar (symbolizing Asherah?). From the main hall one entered an inner room, trapezoidal in shape with plastered benches along its walls. It remains unclear whether the cultic focal point in this temple was in the main hall or the inner room. The building has a western wing with three rooms, one of them a small chamber with a narrow stone-lined pit surrounded by benches; its function remains obscure. A larger stone-lined pit was found in a spacious courtyard in front of the temple. It perhaps served as a silo or was used in some other capacity related to cult practices.

The plan of the temple, although unique, is somewhat reminiscent of several Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I temples defined as “temples with indirect entrances and irregular plans.” The temple at Beth-Shean represents the earliest example of such temples in the southern Levant. The temple was intentionally abandoned after a certain period of use, perhaps due to earthquake damage, which distorted and cracked walls and floors. Its ruins were filled and leveled in preparation for the construction of the level IX sanctuary courtyard. As a result, the building was devoid of finds.

THE LATE BRONZE AGE IB–IIA: STRATA R1b AND R1a. The University Museum expedition uncovered a large architectural complex in level IX, attributed by A. Rowe to the time of Thutmose III and by other scholars to the fourteenth century BCE. Much of this complex, except the southeastern part, which had been removed by the previous expedition, was cleaned and investigated by the new expedition (which termed it stratum R1a). In the western wing of the complex, an earlier phase of level IX was found (stratum R1b). In the eastern part (east of the courtyard), only one architectural phase from this level was discovered (the original level IX as published), built directly above the latest Middle Bronze Age II remains.

In stratum R1b a large building with several large rooms stood in the area west of the courtyard. A circular installation similar to the one defined by Rowe as a “roasting pit” was found there and two more such installations were found in other parts of the area, attributed to both strata R2 and R1. They indeed appear to have been used for roasting (perhaps sacrificial) animals.

In the southern part of the area, the remains of the casemate structure uncovered by the University Museum were examined. It became clear that these cannot belong to an outer fortification, as has been suggested in the past, since there were stumps of walls continuing southward. One of the rooms was excavated and contained an elaborate stepped bath installation. It appears that this row of rooms (including the one containing the “lion and dog” orthostat) belonged to a large building—a residence or palace—which stood at the southern edge of the mound and was significantly destroyed by erosion or cut away during the Roman period. In the northeastern corner of area R, a part of level IX (stratum R1a) that was excavated by the new expedition has shown that this level was destroyed by a fierce conflagration.

Rich pottery assemblages from strata R1a and R1b were recovered, containing mostly local Canaanite types. Imported pottery was very rare. A small number of Egyptian forms (“flower pots,” bowls, and tall bottles), probably of local manufacture, were found, indicating that Beth-Shean was occupied by Egyptians by the fifteenth century BCE. Special finds from this level include a painted sherd depicting a man playing a trumpet of an Egyptian type.

A short Akkadian inscription on a clay cylinder was found at the foot of the mound, in the dump of the previous excavations. It bears a message from Tagi, governor of Ginti-Kirmil, to Lab‘ayu of Shechem—two figures well known from the Amarna Letters. The discovery of this inscription must be related to the status of Beth-Shean as an Egyptian stronghold during the Amarna period, which corresponds to level IX.

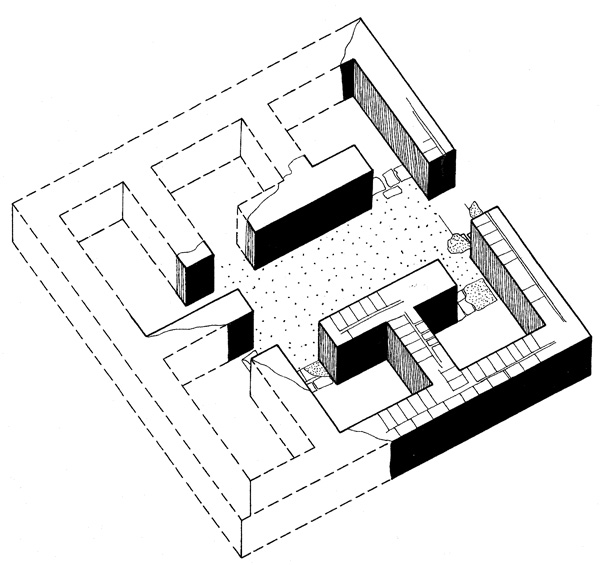

THE LATE BRONZE AGE IIB: THE NINETEENTH DYNASTY. Levels VIII and VII of the previous excavations were dated to the Nineteenth Dynasty (published fully in 1993 by F. W. James and P. E. McGovern). The new excavations did not reach level VIII, while remains of level VII were excavated in areas N (stratum N5) and Q (strata Q3 and Q2).

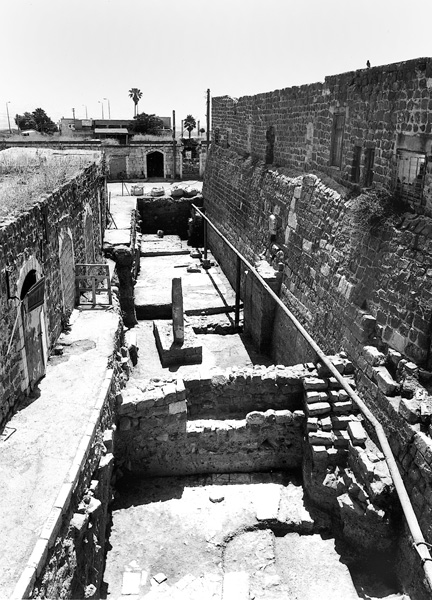

In area N, several structures on both sides of a north–south street were revealed. The eastern structure is part of a massive mud-brick building that was probably located close to the northeastern outer corner of the town. This appears to have been one of the Egyptian governmental structures at Beth-Shean, recalling the so-called migdol excavated by the University Museum in the southwestern part of the Hebrew University expedition’s area R. Its walls are 1–2.5 m wide. The excavated part contains a large hall and two small chambers used for storing grain. As no entrances were found, these rooms were probably in a basement. The building was destroyed in a heavy conflagration c. 1200 BCE. A large assemblage of pottery from this building included much local pottery, an imported tall-necked Egyptian jar, a fragment of a debased Cypriot milk-bowl, and a complete collared-rim pithos of unique form. It should be noted that collared-rim jars are extremely rare in the subsequent Iron Age I levels at Beth-Shean. West of the street several rooms and installations were excavated. One of the rooms probably belonged to a high-ranking person, as it contained a group of five Rameside scarabs, one of them with a rare dedicatory inscription. Among the other finds are an Egyptian bronze razor and a unique fork-like shafted bronze tool.

In area Q, excavation below “the governor’s house” (building 1500 of level VI) recovered remains of two earlier strata (Q3 and Q2). Of stratum Q3 only a small area was revealed; it includes a plastered sitting bath. A large building of stratum Q2 is constructed of mud brick without stone foundations, and has mud-brick floors, both reminiscent of Egyptian architecture. The building measures 20 by 20 (?) m, its outer walls are massive, and its inner space is divided into rooms and corridors by a network of subsidiary brick walls. The plan resembles the contemporary Egyptian fortress at Deir

In area S, the lowest level reached in the new excavations is stratum S5, which may correspond with level VII or late VII, but it was excavated only in small probes.

No evidence for an abrupt, violent end to level VII was found in any of the areas mentioned above. The buildings went out of use and were replaced by new ones in the subsequent period, yet the town plan of level VII was maintained in level VI, as shown by both the primary and renewed excavations. Thus the transition from the Nineteenth to the Twentieth Dynasty at Beth-Shean appears to have been marked by a gradual development, change, and rebuilding of the town.

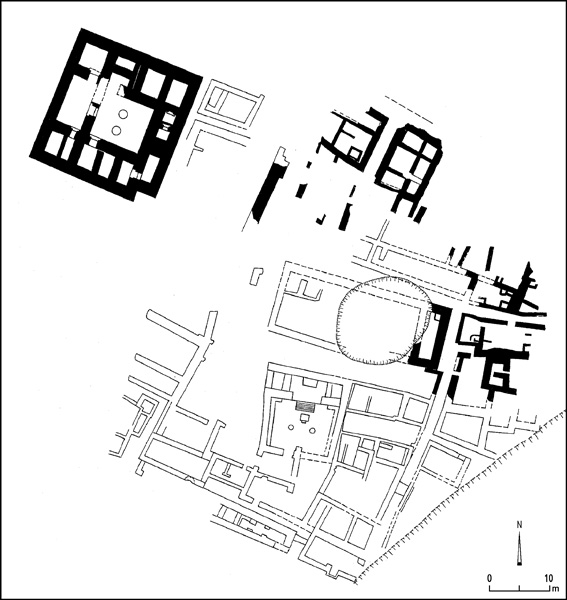

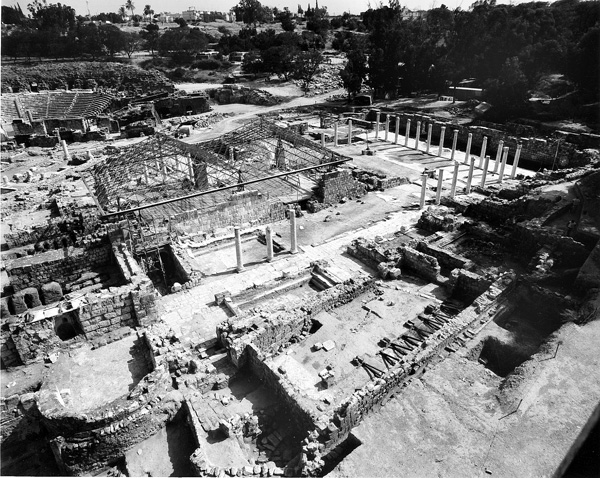

THE IRON AGE IA: THE TWENTIETH DYNASTY. A large area of level VI, the Twentieth Dynasty Egyptian garrison town, was excavated by the University Museum expedition. The new excavations included examinations of buildings 1500 and 1700 (areas Q and N, respectively) and their surroundings (all excavated by the University Museum expedition), and a large residential area at the eastern end of the mound (area S).

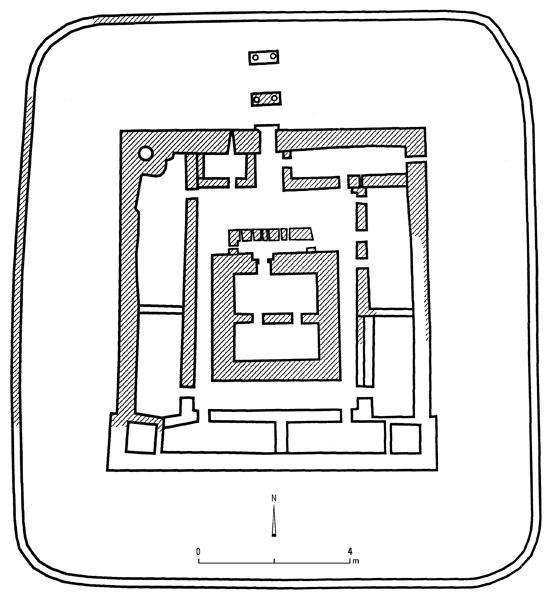

Area Q. Building 1500, the level VI “governor’s house,” was completely exposed in the previous excavations, yet only a schematic plan was published. Cleaning of what remained from this building (stratum Q1) and excavation below its foundation levels made it possible to draw an accurate plan of it and study its history. The basalt stone foundations of the building were laid exactly on the outer walls of the earlier building of stratum Q2 (see above). Thus, in terms of general town planning there is continuity between strata Q2 (level VII) and Q1 (level VI). However, the new building marks a substantial change in the function of this area during the early Twentieth Dynasty: the fortress or administrative building of stratum Q2 was replaced by a small governor’s palace, an elaborate manifestation of the Egyptian presence in the form of an Egyptian-style reception hall, stone doorsills, and inscribed door jambs with Egyptian hieroglyphic dedications. This was probably the residence of Ramses-Weser-Khepesh, whose inscription on a stone lintel was found further to the east (in the Hebrew University expedition’s area S). Analysis of the architecture based on the location of the stone doorsills indicates that the main entrance to the building (which was not preserved) was through the northwestern room, and not in the middle of the western wall, as proposed by the excavators.

Area N. Building 1700 of the University Museum expedition was cleaned and excavations were carried out below its walls. The northern and eastern walls of this building have massive basalt stone foundations; it became clear that these postdate level VI structures and floors to its north (strata N3a and N3b). Thus these walls must be attributed either to the eleventh century BCE (late level VI) or the Iron Age IIA, when similar structures were constructed further to the east, in area S (stratum S1). Massive brick walls attributed to building 1700 south of these stone walls belong either to the time of the stone walls or to an earlier building of level VI, yet this was difficult to determine. Stone doorsills marked on the plan of the University Museum expedition appear to have been found out of their original context. Thus the very existence of building 1700 as an Egyptian residency during the Twentieth Dynasty is questioned.

In the northern part of area N, the ruined buildings of stratum N4 (late thirteenth century) were rebuilt in stratum N3b on a somewhat different plan, and modified in stratum S3a (both contemporary with level VI, the Twentieth Dynasty). The general town plan of N4, including the street, was retained in stratum N3. This level was already excavated by the University Museum expedition, thus no intact floors were found. During the cleaning of the previous excavation surface, a scarab of Ramses III and a sherd of a Mycenean IIIC bowl were found.

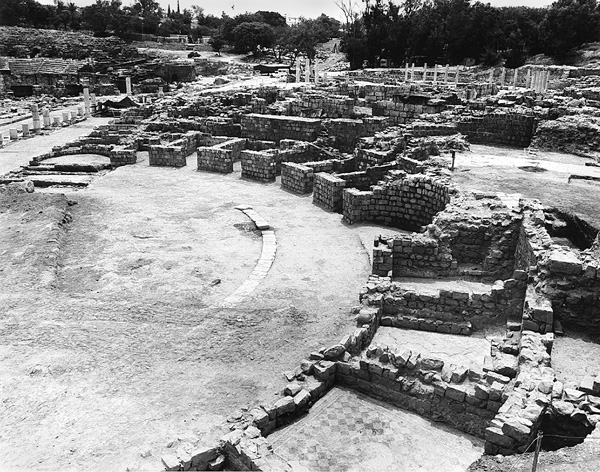

Area S. An area of 700 sq m of a residential quarter was excavated here, representing a continuation of the level VI residential area uncovered by the University Museum expedition further to the south. Two occupational phases—strata S4 and S3—can be attributed to the period of the Twentieth Dynasty. The total accumulation of debris in these two strata was up to 2.5 m deep. They appear to correspond to late level VII (which was defined in only a few places during the previous excavations) and level VI, respectively. In stratum S3, two sub-phases, denoted S3b and S3a, were discerned in several structures. The transition between strata S4 and S3 was probably a gradual, peaceful development, although two fragmentary human skeletons found on stratum S4 floors may hint at partial destruction by an earthquake. Stratum S3 was destroyed by a severe fire, putting an end to the Egyptian garrison town some time in the second half of the twelfth century BCE. The thick destruction layer of this last Egyptian level at Beth-Shean produced many finds.

In strata S4 and S3, houses flank two intersecting streets: a north–south street that is the continuation of a street uncovered in the previous excavations and an east–west street. The houses have courtyards and rooms in which various grinding, cooking, baking, and storage installations were found. Two of the stratum S4 houses have rows of rough stone pillar bases dividing a larger space, a feature that disappears in stratum S3. One of the many ovens found in stratum S3 has a small opening in its side wall, a feature known in Egyptian ovens (e.g., at Deir el-Medineh), but unknown in Canaan.

The pottery assemblages of strata S4 and S3 (as well as N4) are similar: about half the vessels are local Canaanite forms, while the other half—mainly bowls and various small jars—are Egyptian forms produced in a local workshop using typical Egyptian pottery manufacturing techniques, perhaps by Egyptian potters brought to Beth-Shean. Only few vessels had been imported from Egypt, particularly small cups with a single loop handle and one drop-shaped jar with a tall neck.

More than 20 sherds of Mycenean IIIC Middle vessels (mostly stirrup jars, but also skyphoi and a jug) were found in both strata S4 and S3 and are an important addition to the single stirrup jar and the few sherds found in building 1500 and its vicinity. This pottery was probably imported from Cyprus, where it was common during the twelfth century BCE. Since such pottery is rare at other sites in the southern Levant, it probably indicates special relations between Beth-Shean and Cyprus, such as the possible presence of Cypriot or “Sea People” mercenaries in the Egyptian garrison. Hints of the presence of such mercenaries can be found in the northern cemetery, where some of the anthropoid clay coffins were made in a grotesque style that is foreign to both Egypt and Canaan. Beth-Shean provides a well-dated context for this pottery style in two strata dated to the time of the Twentieth Dynasty.

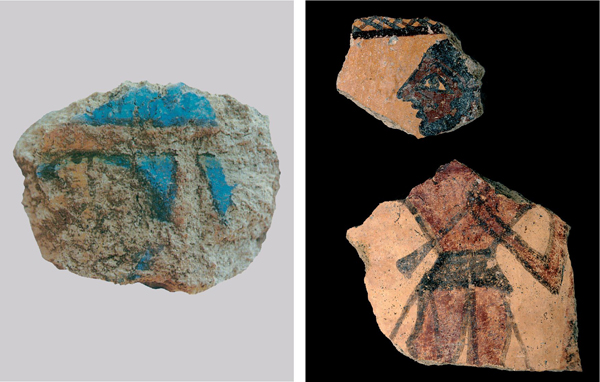

Architectural decoration and various finds attest to the high status of the Egyptian population of this area. One of the stratum S3 buildings produced fragments of wall paintings in black, red, blue, and yellow on mud plaster, most probably in Egyptian style. The fragment of an Egyptian stone relief shows a man (the governor?) sitting on a folded stool, his back straight. A short hieratic inscription in ink on a potsherd probably mentions the Canaanite deity ‘Anat. A commemorative scarab of Amenhotep III describing the arrival in the tenth year of his reign of the Mitanian princess Kirgippa, one of six such scarabs known thus far, was found on a stratum S3 floor. It was probably a valuable heirloom kept for generations. Smaller finds include fragments of thin gold leaf that covered various objects; a ram’s head of hammered gold that apparently served as a furniture casing; and elaborate jewelry including gold earrings and pendants, silver rings, and carnelian and other stone beads. In stratum S4, two small hoards of scrap silver pieces were found wrapped in linen woven in an Egyptian technique. Several scarabs and faience amulets with various Egyptian motifs, among them the god Bes and the Horus eye, were common in these strata. Several bullae provide evidence of Egyptian administrative activity. Clay bird-head figurines typical of the Egyptian New Kingdom, one painted in red and blue, were common.

The circumstances of the violent destruction of stratum S3 and its exact date remain unknown, but it may be surmised that it marks the final blow to the Egyptian empire sometime during the days of Ramses IV, V, or VI. The destruction could perhaps have been caused by a local Canaanite attack initiated by neighboring cities such as

THE IRON AGE IB. Evidence for a rebuilding of the town during the later Iron Age I was found in areas S and N. In the southern part of area S, stratum S2 marks the rebuilding of structures that were destroyed by fire at the end of stratum S3. The new walls follow a somewhat different layout. New floors were constructed and in a destruction layer of this stratum a pottery assemblage was found that recalls Megiddo VIA. The north–south street remained in use. In the northern part of area S the structures of stratum S1 appear to destroy all evidence of stratum S2. In area N, stratigraphic evidence for this phase was found, though its floors had been excavated by the previous expedition. It appears that this level corresponds with late level VI of the earlier excavations; it may be suggested that the double temple complex attributed to level V was founded in this period. Stratum S2 is thus interpreted as a Canaanite town following the ruined Egyptian stronghold.

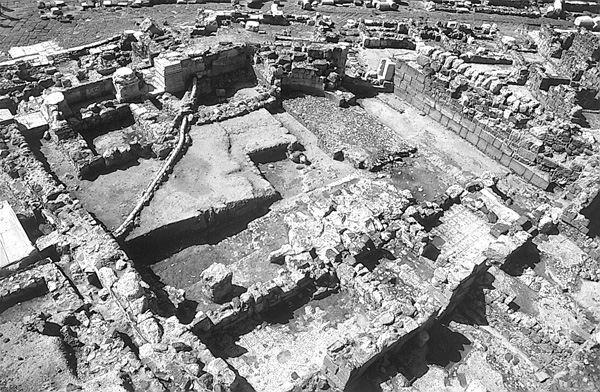

THE IRON AGE IIA. Area S. Stratum S1 in area S corresponds to much of the lower level V of the previous excavations. It is divided into two phases. Both include only scattered remains, as much of this stratum was removed by the previous expedition. The earlier phase (stratum S1b) includes only the remains of a massive stone floor, part of a stone pavement, and the wall of a dwelling. Red-slipped and hand-burnished pottery appears in this phase for the first time.

At least four massive structures were erected in phase S1a of area S. They were partly excavated by the University Museum expedition, and only foundations and a few floor surfaces were available for exploration in the new excavations. Yet the preserved remains indicate that these were large and well-planned structures of a public nature. The walls have basalt foundations with a brick superstructure laid on wooden beams. Three of these buildings were destroyed by a conflagration that fired and melted the bricks. The pottery found in these buildings includes “hippo” jars, red-slipped and hand-burnished bowls, and other vessels typical of the Iron Age IIA horizon in the Beth-Shean Valley.

Area P. Two Iron Age IIA phases were found in small probes in this area. During this period Beth-Shean appears to have been part of the Israelite kingdom. The public structures in area S may be related to an administrative center at Beth-Shean during the time of Solomon, which was destroyed by Shishak (who mentions Beth-Shean in his inscription). It should be recalled, however, that distinguishing between tenth- and ninth-century pottery is extremely difficult, and consequently a ninth-century date (Omride period) for the buildings of phase S1a is not impossible.

THE IRON AGE IIB. The University Museum excavation results concerning the Iron Age II were not entirely clear. They removed all Iron Age IIB remains on the summit of the mound (their levels upper V and IV). Thus a new area (P) was opened in order to examine this period, yielding a stratigraphic sequence. Strata P10 and P9, excavated in small probes, belong to the Iron Age II. Stratum P8, with two sub-phases, belongs to the end of the Iron Age IIA and the beginning of the Iron Age IIB (c. 800 BCE), and includes several walls, installations, and floors. It also produced a rich pottery assemblage from this period.

After a destruction of some sort, a new building was erected in stratum P7. This is a large building, planned on the principle of a four-room house, but lacking pillars. The main entrance leads to a central rectangular hall (probably a roofed space) with entrances leading to two rooms on each of its three wings. The building stands on the edge of the mound and its two western rooms were eroded away; there was no place for a fortification wall in this part of the town. The building was destroyed by a major fire, which caused a thick collapse layer and resulted in the preservation of many finds. This destruction can be attributed to the Assyrian conquest of 732 BCE. The finds include more than 120 complete or almost complete pottery vessels of various types, typical of eighth-century BCE northern pottery. One large jug/jar (from Transjordan?) has a curious seal impression. The household objects found in this building include many loom weights, spindles, and grinding stones. The building appears to have had at least two stories and probably accommodated a high-ranking family. It seems to have been located at the northwestern edge of the inhabited part of the town at that time. North of the building a street was found, and to its east were two construction phases of stratum P7 (denoted P7b and P7a). Following the violent destruction of stratum P7 was a short period of activity (stratum P6) with few floors and scanty walls left by squatters, perhaps dated to the last decades of the eighth century BCE.

Several Hebrew ostraca were found in area S, in the bottom of what probably is an Iron Age II pit. All the inscribed sherds come from the lower part of a single jar; they are administrative lists, including names and numerals. The unusual name zma recurs several times.

THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD. After a gap in occupation lasting over 500 years, settlement on the mound was renewed during the third century BCE. This level represents the foundation of Nysa-Scythopolis, the new name of Beth-Shean until the end of the Byzantine period. Somewhat later (probably in the early second century BCE), the settlement expanded to include parts of Tel

In area P, stratum P5 belongs to the Hellenistic period. Three stratigraphic phases of domestic architecture were found, including thin stone walls, floors, and ovens. The finds include coins of the third to first centuries BCE (the earliest a coin of Ptolemy II), 17 stamped handles of Greek amphorae dated mainly to the last third of the third century BCE, and a rich collection of pottery including imported pottery of the third and mainly the second century BCE. While the stamped handles appear to belong to the period between the foundation of the Hellenistic city (c. 260 BCE?) and its surrender to Antiochus III in 218 BCE, the coins and pottery are from that period as well as the Seleucid period. The end of stratum P5 perhaps came towards the end of the second century BCE with the conquest of Beth-Shean by John Hyrcanus. Nearby Tel

THE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE PERIODS. Only a few pottery sherds and coins were dated to the Early and Late Roman periods in area P (stratum P4) and no architectural features from these periods were found. It appears that while a monumental temple stood on the summit and the city developed at the foot of the mound, the mound itself remained unoccupied in the Roman period.

During the Byzantine period (stratum P3) the entire mound became a residential area, with a round church on the summit. In area P, foundations of a massive building of public character were found; few of its floors were preserved. In a later Byzantine period phase, a new house was added at the northern edge of area P, which had a large room with a mosaic floor decorated with a frame of vines and amphorae. In area H, a small probe close to the northern edge of the mound, a street, and two façade walls of elaborate Byzantine buildings were excavated. In area L, part of a Byzantine building was uncovered, with a deep constructional fill. Byzantine plastered cisterns and a massive foundation in area S were perhaps related to the round church that stood nearby.

THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD. The University Museum expedition had uncovered a well-planned Early Islamic residential quarter, which covered the entire area of the mound. It had straight, wide intersecting streets and large dwelling units. Part of one such dwelling was excavated in area P (stratum P2); it consists of several rooms and courtyards. Umayyad pottery was found, as well as a few coins. In area L, parts of Early Islamic period walls were also uncovered. In both areas (as well as in the previous excavations) there was no architectural continuity between the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods.

THE MEDIEVAL PERIOD. The University Museum expedition had unearthed a gate at the northwestern corner of the mound and a fortification wall that surrounded the entire mound. These were dated to the Late Islamic period. In area P it became clear that the fortification wall (stratum P1) was constructed after the Early Islamic period buildings went out of use. Part of a large building—a hall with pilasters that probably carried arches—was uncovered in the northern part of area P. It had two construction phases. The small amount of pottery found on its floors is medieval (twelfth–thirteenth centuries CE?). This fortified town apparently did not last long, as large parts of the mound remained unbuilt. It is possible that this was a Crusader period town that existed beside the Crusader fortress excavated on the opposite ridge, to the south of the Roman period city (see below).

SUMMARY

The Hebrew University excavations at Tel Beth-Shean have refined our knowledge and shed more light on the history of the site from the end of the fourth millennium BCE until the medieval period. During most of this time (from the Early Bronze Age III through the Iron Age II) it appears that only the summit of the mound was settled, an area of 4–5 a. Only in the Early Bronze Age I and the Hellenistic (?) and Byzantine to Islamic periods was the entire mound settled.

During the Early Bronze Age I, it was a rather large settlement with a public building at its summit, which had some administrative function, perhaps related to the storage and redistribution of food. During most of the Early Bronze Age II, there was a gap in occupation with brief activity at the end of that period. In the Early Bronze Age III, the summit of the mound was settled by producers of Khirbet Kerak ware; this settlement lasted for a considerable period of time and is represented by five stratigraphic phases. During the Intermediate Bronze Age, a short lived, perhaps seasonal, settlement existed on the mound, followed by an occupation gap until c. 1700 BCE. During the late Middle Bronze Age II, there was a rather small yet well-planned town with three successive strata. All that remained of this town in the Late Bronze Age I was a small shrine, perhaps with a small settlement around it. Not being one of the major Canaanite cities, the site fell prey to the Egyptians, who converted it into a governmental center, probably shortly after the establishment of the New Kingdom empire in the fifteenth century BCE. The town continued to serve the Egyptian government for approximately 300 years, until the late Twentieth Dynasty. Two violent destructions during this period (at the end of levels IX and VII) were immediately followed by the reconstruction of the town, until its final destruction by fire towards the end of the period of Egyptian presence in the second half of the twelfth century BCE.

Monuments and statues erected at the site during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties are evidence of bold Egyptian propaganda and ostentatious display. It appears that throughout this period, Beth-Shean was no more than 4 a. in area. It did not develop into a large town but essentially remained what it was initially—an Egyptian stronghold settled mainly by Egyptians and their mercenaries, some of them perhaps of foreign origin (the so-called Sea Peoples).

During the eleventh century, after the Egyptians had left, Canaanite culture continued to thrive at Beth-Shean and nearby sites. During the Iron Age IIA, the site appears to have been an administrative center and was destroyed by severe fire, perhaps during the invasion of Shoshenq I (the biblical Shishak). Later the town was rebuilt at least twice. Elaborate buildings stood there in the eighth century, until the devastating Assyrian conquest in 732 BCE. A short period of squatter settlement was followed by a break until the third century BCE, when the Hellenistic town was founded. This prosperous settlement came to an end in the late second century BCE, though some activity continued during the first century BCE. A gap during the Roman period (with the exception of the temple on the summit) was followed by the establishment on the mound of a residential area, with a round church at the summit, during the Byzantine period. In the Early Islamic period, a new and elaborate residential quarter replaced the Byzantine one. During medieval (Crusader?) times, the mound was fortified and several large buildings were erected on it.

AMIHAI MAZAR

THE HELLENISTIC TO EARLY ISLAMIC PERIODS: THE ISRAEL ANTIQUITIES AUTHORITY EXCAVATIONS

EXCAVATIONS

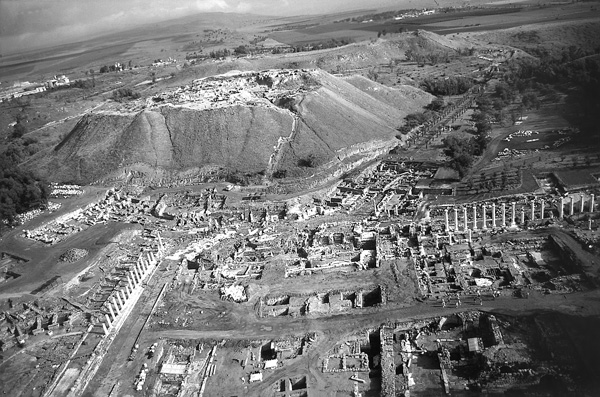

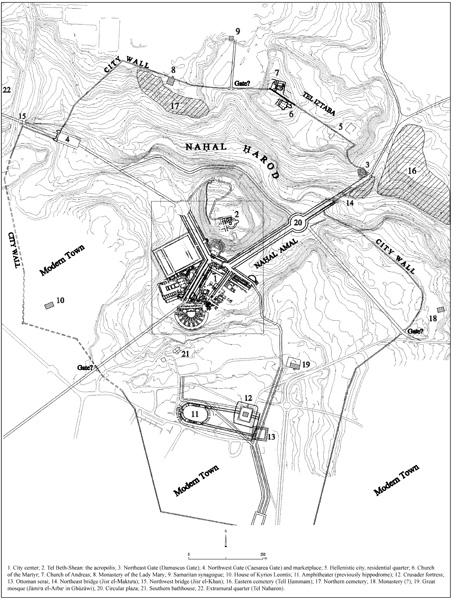

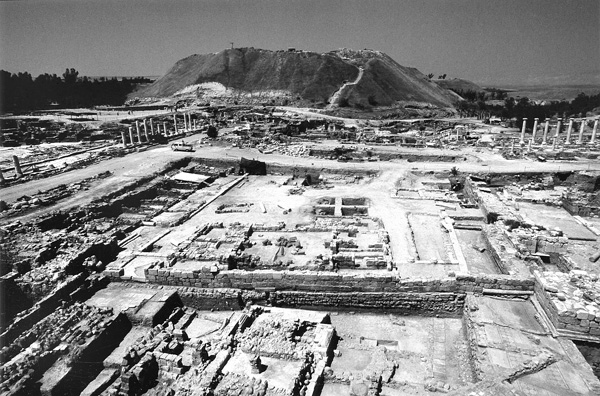

Large-scale excavations have been conducted at Beth-Shean since 1986 within the framework of the Beth-Shean Archaeological Project, under the direction of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), accompanied by extensive restoration and conservation work. Recently, a detailed model of the city was erected at the site entrance and illustrations and explanations were set up along the visitors’ path. Excavations in the civic center of remains from the Roman–Byzantine and Umayyad periods and on Tel

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD. Hellenistic period remains were revealed at Tel Beth-Shean, in a continuation of the excavations of the University Museum expedition, and mainly on Tel

The excavation of the Hellenistic stratum at Tel

The results of the excavations indicate that Nysa-Scythopolis was first founded as a military post on Tel Beth-Shean by Ptolemy Philadelphus c. 260 BCE, along with other outposts such as Philoteria (Beth

The mixed population of the city is evident from the priestly inscription from the second century BCE found on Tel Beth-Shean, which mentions the priest of the cult of the king, Hyracalides son of Serapion, who was of Egyptian descent, alongside Evibelius son of Epicrates, of Greek descent. The inscription is also instructive on the cult of Zeus, the official cult of the Seleucid Dynasty, and of the other gods worshipped in the city. Alongside the cult of Zeus was the cult of Dionysus, the patron god of the city, called “the founder” in a Roman inscription found in the excavations. From the city’s coinage it is evident that Zeus the father and Dionysus the son were associated with Tyche/Nysa, the city goddess and nursemaid in the founding myth of Nysa-Scythopolis, as told by the Roman naturalist Pliny (NH V, 74). From the

The city is mentioned in the description of the campaign of Judas the Maccabee to free the Jews of Gilead (1 Macc. 12:29–31), and again in connection with the events of the year 143/2 BCE when Tryphon confronted Jonathan the Hasmonean within the city borders (1 Macc. 12:40–41; Antiq. XIII, 188). At the end of the second century BCE Epicrates surrendered the city to the Hasmoneans in return for money (Antiq. XIII, 280; War I, 66), and the destruction and burning of the city can be attributed to the conquest by John Hyrcanus (c. 108/107 BCE). Nysa-Scythopolis thus joins other Hellenistic cities such as Neapolis (Shechem) and Mareshah where signs of destruction may be attributed to the Hasmonean campaign. Little is known of the history of the city after the Hasmonean conquest, and the excavations have revealed that the city was unoccupied in this period and remained in ruins until the conquest of the land by the Roman general Pompey in 64/3 BCE. At this time all the Hellenistic cities in the region were liberated and returned to their inhabitants, rebuilt and perhaps even refounded, and incorporated into the province of Syria, which was established at this time (War I, 155–157; Antiq. XIV, 74–76). The city of Nysa-Scythopolis, like many others in the region, began calculating years from the conquest of Pompey.

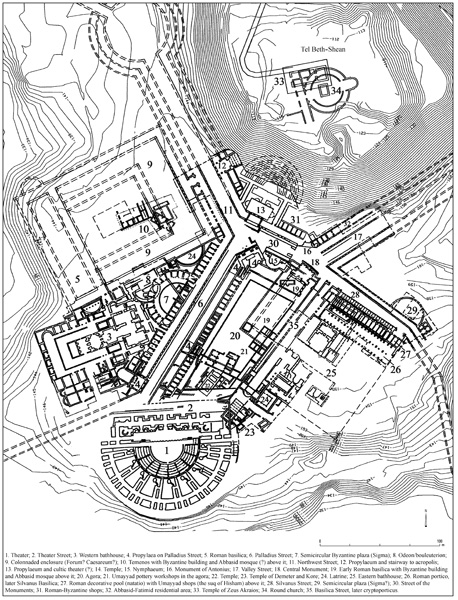

THE ROMAN PERIOD. Based on the coins of the city, Gabinius, the Syrian governor in 57–55 BCE, can be accredited with the reestablishment of Nysa-Scythopolis, which was now also called Gabinia. The location of the city shifted again, this time from the well-defended mounds in the north to the basin of

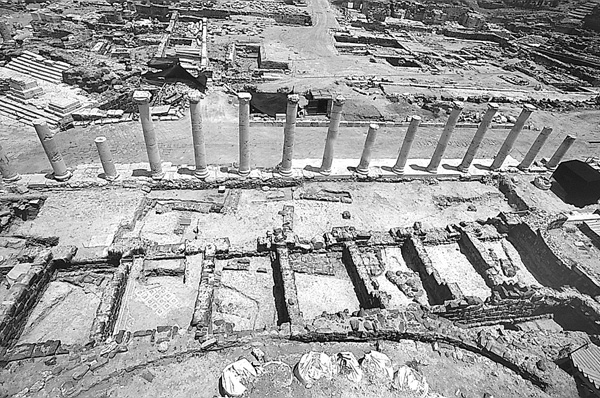

In the civic center, the agora (or forum) stood as the focal point of the urban plan, as was customary in Roman Republican city planning in the West. In the southeastern part of the agora was a temenos that contained two temples and in the northeast a basilica. To the south of it a theater was built whose remains revealed two construction stages: the first, dated to the days of Tiberius, was discerned below the foundations of the later theater, erected above it in the days of Septimius Severus. On the eastern side of the agora a 12-m-wide road paved with basalt slabs led to the temple enclosure from the north. From the excavations it appears that another road ran along a similar route to that of Palladius Street to the west of the agora, and thus it seems that the northwestern entrance to the city from the direction of Caesarea was already in use in this period. To the northeast of the agora, the remains of a bathhouse were found by the Hebrew University expedition and at the foot of the tell were the remains of shops and another road (see below). It seems, therefore, that the urban plan of Nysa-Scythopolis was already well established in the first century CE, a plan that attained monumental magnificence during the second century CE.

Although historical sources regarding Nysa-Scythopolis during this period are vague, the city was apparently included in the territories awarded to Cleopatra by Anthony. Nysa-Scythopolis was not among the cities annexed by Octavius to the kingdom of Herod and thus continued to be part of the Syrian province. It appears that the establishment of Caesarea as a central port city and the location of Nysa-Scythopolis at the important regional crossroads connecting the coastal cities with Damascus on the one hand and the trade centers of Transjordan and Caesarea on the other lent the city a greater degree of importance, security, and economic prosperity. This situation may have been disturbed, however, by the massacre of the Jews that took place in the city following the riots in Caesarea in August/September 66 CE (Josephus, War II, 457–469), an event that resulted in the stationing of a cavalry unit in the city under the command of Neopolitanus. After the siege of Jotapata (Yodfat), the Fifteenth Legion was sent by Vespasian to rest near the city, most probably in the legionary camp at Tel Shalem (Josephus, War III, 412). The unrest that shook the country between 117–120 CE, in the years preceding the Second Jewish Revolt, brought about the upgrading of Judea, in whose territory Nysa-Scythopolis was now included, to the status of consular province. As a result, an additional legion was stationed in its territory and the legionary headquarters were established at Kefar Othnai (Legio) on the edge of the Jezreel Valley, on the road from Nysa-Scythopolis to Caesarea.

The annexation of the Nabatean kingdom, the establishment of Bosrah as the capital of Provincia Arabia, and the construction of the Via Nova Traiana, reflecting the eastern policies of Trajan, continued to strengthen the status of Nysa-Scythopolis and elevated the importance of its location on the central crossroads between the East and the coastal ports. In the spring of 130 CE, Hadrian visited the city and was received by the governor, Tinius Rufus, as evidenced by a number of inscriptions found within the temple compound of the agora. The visit constituted part of a direct continuation of the regional policies of his predecessor, as can be seen in the administrative and military organization of the province, including the building of the extensive road network of the region. The suppression of the Second Jewish Revolt and the establishment of peace in the province brought about the construction of a triumphal gate in the name of the Senate and the Roman people within the city region, most probably in the legionary camp at Tel Shalem to the south of the city.

Nysa-Scythopolis was now entering its golden age. Although Trajan and Hadrian were the founders of the political and economic infrastructure of the city, most of the fruits of their consequent policies came under their immediate successors, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. One may also attribute to this period the first use of the Gilboa quarries, which comprised the source of limestone masonry and architectural elements for the magnificently designed monumental buildings of the city in this period.

The Streets and Gates of the City. During the second century CE the architecture of Nysa-Scythopolis, like many other cities in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, was characterized by monumental design. Its colonnaded streets led past grand buildings and the city plan was richly adorned in magnificent and monumental architecture that would continue to reflect the splendor of Nysa-Scythopolis throughout the Byzantine period. To the north of the city, two of the five monumental city gates were uncovered, erected in the first half of the second century CE as free-standing city gates, at the end of the colonnaded streets of the city. These monumental city gates incorporated a central arch and flanking towers, the central arch elaborately decorated on both façades (inner and outer) with free-standing columns bearing a rich entablature while ornate niches in its wall housed statues.

The Northeast (or Damascus) Gate is located on the northern bank of

A colonnaded street led from the bridge to a circular plaza, 52 m in diameter, surrounded by porticos and shops and once boasting a tetrapylon in its center, the remains of which were found in the plaza. It was a juncture for this colonnaded street leading from the northeast, the continuation of which—known as Valley Street, 24 m wide including its adorned porticos and shops—ran along

The Northwest (or Caesarea) Gate stands at the northwestern end of Northwest Street, a magnificent colonnaded street originating in the city center. This free-standing gate of an unwalled city is situated on the southern bank of

Northwest Street probably reached another circular plaza located at the foot of the tell. This plaza, like its predecessor to the east, would have been the meeting point of four colonnaded streets: Northwest Street, originating in the civic center, a street (not on plan) from the Southwest (or Neapolis) Gate, the street that encircled the tell from the north, and another from the Northwest Gate. In this way a well-planned, belt-type junction connecting all four main city gates was constructed. It incorporated within the city a central crossroads, which enabled travelers from the coast or inland to reach their destination, whether Damascus or Arabia, without entering the hectic civic center, while remaining within the city’s jurisdiction and bound to its tax regulations.

On the western side of Northwest Street, next to the civic center, a grand compound surrounded by porticos of the Ionic order was exposed, measuring 135 by 102 m. A magnificent propylaeum led from the colonnaded street into the central axis of this enclosure. A monumental basilica built in the Corinthian order stood on a podium on the western side of the compound and it seems that a temple stood in the center. Alongside the southern portico of the compound was an odeon, a small roofed theater that probably also functioned as a bouleuterion, where the city council convened. It seems that the porticoed compound with its basilica, built in the first half of the second century CE, was a caesareum—in imperial architecture a temenos dedicated to the cult of the emperor (but see discussion below on the results of the Hebrew University expedition in the compound, referred to there as the “new forum and temenos”).

From the foot of the tell another colonnaded street (Palladius Street) led southwest towards the theater. Below the street and its western portico there was evidence that a similar paved street oriented slightly westward already existed in the first century CE. From its earlier stage in the first half of the second century CE, Palladius Street was a magnificent colonnaded thoroughfare of the Ionic order, bordered on either side by mosaic-paved porticos and shops. It was built on the slope of the western hill and is therefore situated at a higher level than the agora to the east. As a result, the shops on its eastern side were built on top of the shops of the agora portico. This first floor of shops, opening eastward toward the agora, had numerous installations and artifacts preserved within them, including shelves for merchandise and storage jars for food. The second-floor shops opened westward toward the portico of the colonnaded street. In two places along the eastern portico of the colonnaded street, in the center and near its northeastern end, propylaea and wide staircases descended from the colonnaded street to the agora.

The remains of another propylaeum dating to the second century CE were found below the propylaeum built at the southwestern end of Palladius Street at the beginning of the Byzantine period. It seems that both the earlier and later propylaea led to the western bathhouse, built in its various stages on the hill at a higher level than the colonnaded street. At the end of the colonnaded street stood the ruins of an arch that marked the southwestern entrance to the street from the theater street plaza.

To the southwest and perpendicular to Palladius Street are the remains of another street running along the façade of the theater (Theater Street) and the façade of the western bathhouse further west. At the junction of the streets were found the foundations of a nymphaeum whose superstructure had been removed at a later stage and its plan is therefore unclear. Between the nymphaeum and the propylaeum leading to the western bathhouse, the remains of a large latrine were uncovered, its sewage system incorporated into the main drainage system of Palladius Street.

To the south of the theater, between it and the hippodrome built outside of the civic center, the excavations of F. Vitto revealed the remains of another city gate, apparently the southern one, on the road to Jericho and Jerusalem (Aelia Capitolina). In the absence of a city wall, the city gates stood as magnificent monuments at the ends of the streets over the pomerium ditch, marking the administrative and judicial borders of the city and the point where the regional network of roads entered its jurisdiction.

The Agora Temples. To the north and northeast of the theater façade, within the agora, a cultic compound was erected containing two temples originally built in the first half of the first century CE, their façades renovated in the first half of the second century CE when the civic center was refurbished. The first temple, located north of the theater postscenium wall, was a rectangular building erected on a podium, its walls decorated with base and cap moldings incorporating lion heads, with a staircase leading to it from the north. It had a Corinthian tetrastyle pronaos and a libation installation on the far side of the cella. In the early second century CE, the temple was renovated and surrounded by Corinthian columns, turning it into a peripteral temple. At the beginning of the Byzantine period the temple was dismantled and covered with earth, some of its components reused in other buildings, leaving very little evidence on its architectural setting. An inscription found nearby, dated to the first century CE, mentions Cassiodorus, builder of the temple, priest of god and emperor, who was also the head of the gymnasium and the city agoranomos. The inscription does not mention the name of the god to whom the temple was dedicated.

To the east of this temple was another cultic complex, in the center of which was a square monument built on a high podium and surrounded by columns. Within it was a round space with a bema on the southwestern side, upon which a statue probably stood. From the north, a staircase built above a vault ascended to the building. Within the vault a wide variety of finds attesting to cult practices was found, including offerings, figurines, and inscriptions. Alongside the central monument were two nymphaea built on terraces, one above the other. Between them, a covered portico led to the vault. The upper nymphaeum was round and in its façade were incorporated inscriptions and altars. The lower nymphaeum was rectangular and its façade incorporated fountains in the shape of lion heads. At the back of the temple were rooms decorated with colored frescos, and in front of it was a plaza with a built altar. A rich collection of inscriptions on marble slabs and altars was found within the temple enclosure, providing evidence that the cultic complex was almost certainly dedicated to Demeter and Kore, whose worship is also depicted on the city coins. A paved street led from this cultic compound toward the northeast along the eastern side of the agora.

The Eastern Bathhouse. To the east of the agora, a large bathhouse (120 by 93 m) was exposed extending between Silvanus Street and the agora’s eastern temple. It was originally built in the first century CE and was expanded in the second century. Both this and the 100-by-70-m western bathhouse were enlarged significantly in the Byzantine period and thus occupied a substantial area of the city’s civic center, indicating their important role in the life of the city residents and visitors.

The construction of the eastern bathhouse within the streambed of

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. From 324 CE onward, the region is characterized by the slow but steady establishment of Christianity and the decline of paganism, a cultural struggle whose signs are clearly discernible at Nysa-Scythopolis. However, despite Christianity’s victory, the roots of pagan tradition and culture were still evident in the city during the sixth century CE and the urban landscape differed little from that of the imposing Roman city. A significant factor that determined the design of the Byzantine city, apart from the religious-cultural changes, was the earthquake of 363 CE, which led to the reconstruction of various parts of the civic center. A number of years later, in approximately 389 CE, the province of Palestine was redivided into three administrative provinces and Nysa-Scythopolis became the provincial capital of Palaestina Secunda. The borders of the new province included the Jezreel Valley and Lower Galilee, northern Gilead in Transjordan, and the Golan. The city thus became a center of provincial administration, commerce, and business, and the governor (archon) seated at Nysa-Scythopolis used municipal and provincial tax revenues to rebuild the city. Many building inscriptions from this period mention the numerous governors who renovated the city’s streets and porticos, squares and monuments, bathhouses, theater, amphitheater, and odeon, and built water systems and the city walls.

During the Byzantine period, urban settlement and population growth reached their zenith. This was manifested in the city by the expansion of the already built-up area and the construction of new suburbs on the outskirts of the city and outside the walls, as at Tel Naharon, and to the east and west of the city. The population of Roman Nysa-Scythopolis, estimated at c. 20,000 in the second century CE, had doubled by the first half of the sixth century. The inhabitants of the city in this period were diverse; alongside the growing Christian community was a large number of newly converted pagans, a sizeable Jewish community, and a considerable Samaritan community, one of the largest outside of Samaria and second only to that of Caesarea, capital of Palaestina Prima. The notables of the Samaritan sect, as evidenced by the inscriptions and the sources of the time (Cyril of Scythopolis), wielded substantial political influence in the provincial government and even in the court of the emperor.

The Reconstruction of the City. Some of the repairs and reconstructions discerned in the buildings of the city can be attributed to the damage caused by the earthquake of 363 CE. The scaenae frons of the theater was rebuilt in this period, now with two stories, and the size of the theater was decreased by a third. On the southwestern side of Palladius Street a new propylaeum was built leading to the western bathhouse, making use of architectural elements from the earlier propylaeum, which was apparently destroyed in the earthquake. Near the theater a dedicatory inscription was found, not in situ, stating that the city was renovated in the days of Abalbius the great metropolitan, probably in the aftermath of the earthquake of 363 CE.

Other building projects can be attributed to the city’s new status as provincial capital. For example, the governor, Flavius Prophirius Palladius, laid a new mosaic floor in the portico of the colonnaded street that bears his name. The western and eastern bathhouses were expanded, and halls, porticos, and many new rooms—all richly decorated—were built, as were public latrines alongside them. It appears that the two bathhouses (thermae) in the center of Nysa-Scythopolis were not intended solely for the inhabitants of the city, but also for the stream of visitors arriving to the provincial capital on matters of business and trade. This explains why the governors named in the many inscriptions found in the western bathhouse deemed it worthwhile to invest so extravagantly in them. To the south of the theater a smaller bathhouse (balnea) was built, representing a neighborhood bathhouse the likes of which would have been located in other neighborhoods of the city. The remains of two such bathhouses have been found in previous excavations in the southern sector of the city, which was added to the city’s jurisdiction during the Byzantine period.

A significant change in the appearance of the city was associated with the rise of Christianity. This is seen in the dismantling and sometimes even covering-over of the temples, which may have been partially destroyed by the earthquake of 363 CE. The temple of Zeus Akraios, which stood on the top of the tell, was dismantled and a round church was erected on its foundations. The agora temples were dismantled and covered, the level of the agora was raised and it was redesigned. The temple in the center of the caesareum was also dismantled and its elements reused in other buildings. The quadriporticus was abandoned and by the end of the Byzantine period it was partially covered by construction debris.

The renovation of the city reached its peak at the beginning of the sixth century CE, during the reigns of Anastasius (491–518) and Justin I (518–527), the period from which most of the building inscriptions in the city date, indicating the administrative and economic power of the provincial capital at this time. The reconstruction projects from this period, most of a grandiose, monumental nature, are best recognized in the civic center of Nysa-Scythopolis.

Along the central part of the western portico of Palladius Street, the Sigma was built in 507 CE by the governor of Palaestina Secunda, Theosevius son of Theosevius, who was a native of the city Amisus in the district of Hellenpontus, with the assistance of Sylvanus son of Marinus, the praetor. The Sigma was a luxurious commercial center including taverns and shops built as an arched exedra with a semicircular portico and grand apses in the center and at either end. In the rooms of the Sigma were magnificent mosaics, among them a medallion depicting Tyche and many inscriptions. The complex opened onto a paved plaza from which a wide staircase led to the western portico of the colonnaded street. Palladius Street was renewed and the porticos along it were repaved with marble slabs, which also decorated the façades of the shops. Somewhat later a basilica was built by the governor Flavius Theodorus in the western wing of the western bathhouse. The large hall had meeting rooms (triclinia) on its western side and a colonnaded portico on its eastern, which was repaved; on its northern side its apse was decorated with a colored wall mosaic. Public basilicas of this type, in some of which the cult of the emperor took place, are a well-known component in large bathhouses and their incorporation in these complexes is evidence of the growing importance of the bathhouse in the social and cultic life of the city, long Christianized in this period.

The marble statues of the second-century decorative program of the bathhouses, like those of other structures in the city, such as the theater, the odeon, and the colonnaded streets, remained in place until the early sixth century. As the city became more and more Christian, they were removed and buried. A statue of Hermes was found in the odeon, and in the theater was unearthed another statue of the same god, along with statues of Tyche and Aphrodite. In the eastern bathhouse statues of other gods originally stood in special niches in the frigidarium halls, including two of Aphrodite accompanied by Eros riding a dolphin, Apollo, Leda and the swan, Heracles, Athena, Zeus and an eagle alongside a citizen in a toga, and a bull. Most of the statues were buried without heads, which may have been buried separately. In the Sigma a mosaic pavement depicts Tyche and some of the inscriptions of the period incorporate quotes from classical literature. The theater, the odeon, the amphitheater, and the bathhouse with its newly installed basilica continued to be used by the citizens of the city, clear evidence of the deep roots of the Hellenistic culture still prevalent in the life of the city, which apparently did not conflict with the change in religion.

The agora was also renewed and its porticos repaved. The mosaic floor of the western portico depicts a scene of animals including a lion and a zebra. A new portico was built to the south of the agora, separating it from the theater. In front of the theater was built a splendid portico (porticus post scaenam) and to the north and northeast of it two intersecting paved plazas with a wide staircase leading from the first plaza to the façade portico of the theater. Next to the second plaza were erected a nymphaeum, a staircase leading from the plaza to the eastern side of the theater entrances, and another staircase leading down to the latrines of the eastern bathhouse.

At the beginning of the fifth century CE the city was encircled by a fortification wall incorporating the city gates, which until now had been free-standing monuments at the ends of the main colonnaded streets of the city and had remained unchanged in plan and location. The wall, c. 4.8 km in length, traverses Tel

Churches and Monasteries. The church erected on the tell was the only one built next to the civic center. This is in contrast to cities such as Gerasa, Pella, Gadara, and many others where there are numerous churches in the civic center. In addition, no basilica, not to mention a cathedral, has been found in the city, which served as the seat of the bishop. The church at the top of the tell was most probably built in the second half of the fifth century CE, a long time after the temple to Zeus Akraios was destroyed and dismantled. It was built in the style of an ambulatory church with an unroofed central area, examples similar to which are found in the region. These churches were usually not intended for the use of the general community and it is possible that the church on the tell was dedicated to John the Baptist and perhaps even comprised part of a monastery. All other churches were located on the outskirts of the city, on Tel

The small, single-apse church (Church of Andreas) on the western summit of Tel

The newer church (Church of the Martyr) is larger, also built as a basilica with two rows of arches dividing it into a central nave and aisles. The three apses to the east were arranged as a trefoil, the central apse containing a synthronon and a bema, at the center of which stood an altar. Below the floor of the bema, paved with colored stone tiles, were found the remains of a reliquary. Chancels once stood in front of the bema and on both side apses. The northern apse contained a decorated marble sarcophagus, which probably originally stood in the cellar of the central apse of the small church outside the wall, and was moved to the new church when the former was destroyed. The northern apse was decorated with a delicately carved latticework chancel screen. On the northern side of the church stood a large chapel with one apse. In front of the church was a narthex with a pedestaled colonnade, the column capitals decorated with crosses. To its north and adjoining the city wall was a kitchen and dining room, and around the church were the rooms of the monastery to which it belonged. All the mosaic floors of the church were decorated with beautiful geometric guilloches and around their edges were designs of fruit and vegetables, plants, birds and peacocks, as well as panels depicting lively hunting scenes containing realistic animals. A fragmentary mosaic inscription found in the narthex mentions a martyr whose name has not survived or was not included. According to the style of the mosaics and the inscriptions, the church was probably built in the first half of the sixth century, very likely with the reconstruction money allocated to the city by the emperor Justinian following the Samaritan revolt of 529 CE.

The biography written by Cyril of Scythopolis on the life of St. Sabas, who visited the city in 518 and again in 531 CE, mentions several churches and monasteries of the city, including the Chapel of Thomas the Apostle, located outside the city on the road to Caesarea; its remains appear to have been uncovered by N. Zori. Cyril also mentions the old Church of the Martyr St. Basilius, which existed at the beginning of the fifth century and also receives mention in the biography of Euthymius. This can probably be identified with the church, described above, that stood outside the city wall before it was rebuilt within the walls as the Church of the Martyr. Its first location connects it to the Samaritan synagogue, which was built some distance to the north, and it may be that both are mentioned in the affair of the massacre of the Christian children by the Samaritans. In the opinion of L. Di Segni, this event was erroneously attributed by Malalas to Caesarea, and actually took place in Nysa-Scythopolis near the Church of the Martyr St. Basilius and the Samaritan synagogue. Also mentioned in the report of Cyril are a monastery called Antananth (spring of figs?); the Apse of John, which may have been the arch of the propylaeum along the street that leads to the Church of John on the tell; and the Church of Procopius, the first martyr of the city, situated in the palace of the bishop, the location of which is still unknown. Near the ruined bridge the monastery of Father Justin was built in 522 and in the middle of the sixth century another monastery (“Monastery of the Lady Mary”) was built to the west of Tel

From the results of the excavations it is evident that a gradual process characterized at first by the cessation of development in the city began in the second half of the sixth century CE. There were no more building inscriptions or other evidence of architectural projects except those related to church buildings. This process reached its height by the end of the sixth–beginning of the seventh century CE. Public buildings were no longer maintained and slowly deteriorated, some were abandoned and even dismantled, and private construction gradually encroached on the public areas. In the porticos of the colonnaded streets poor private dwellings were erected and the once-magnificent colonnaded streets were now neglected and covered with alluvium, becoming virtual alleyways. All this is evidence for the decline of local authority—both the municipal and provincial administration—as well as the central administration of the Byzantine Empire. The Persian conquest did not directly affect the city, but it definitely accelerated these processes, which were by then clearly evident throughout the entire civic center.

THE UMAYYAD PERIOD. The Muslim victory over the Byzantine army at the Battle of Pella in the winter of 635 CE brought about the fall of the city, although not its destruction. The city surrendered and signed a treaty that ensured co-existence with no major concessions, although by now both the status and appearance of Nysa-Scythopolis had deteriorated. Some time after the conquest, the municipal administration was reorganized, retaining its Byzantine components but changing the administrative centers. The capital of Jund el-Urdun, similar in size to the province of Palaestina Secunda, moved to Tiberias, where the ruling bodies of the administration were centered, while Beisan, as Nysa-Scythopolis was now called, lost much of its administrative importance. It was, however, still located on the central crossroads and thus bustled with trade and business. The urban landscape of the city was now somewhat peculiar, in that many of the distinctive symbols of the Roman-Byzantine culture—the colonnaded streets, plazas and city gates, the theater and the agora, and alongside them propylaea, nymphaea, and other monuments—now comprised background scenery, devoid of content, for a city that was slowly changing its way of life and function from that of a polis to a medina. The population of the city also underwent a transformation, and now included a growing number of recently arrived Muslim residents. Arabic was used alongside Greek. Byzantine coins, sometimes restruck, continued in use and it appears that daily life in the civic center, as well as in the churches and monasteries on the outskirts of the city, continued as usual.

Tel Beth-Shean, which rises in the center of the city, mirrors to a great extent the situation in the lower city from the Muslim conquest through the second half of the seventh century CE, during which time continuity was accompanied by gradual change. The tell, which during the Roman period was not inhabited and only contained the temple of Zeus Akraios, slowly changed its appearance during the Byzantine period. Following the erection of the church on the tell, a residential neighborhood grew up around it, possibly connected with the monastery. The remains of a paved road were discerned that ascended from the gate of the tell and ran between the church and the residential area. After the conquest, the church was dismantled or destroyed in the earthquake of c. 660 CE, and the residential area gradually spread into the area of the ruined church and monastery. The street of the tell now changed direction and was paved over the remains of the church. In the Early Islamic period, houses with large courtyards were erected alongside the houses from the Byzantine period, making use of stones and columns from the church, upon which were found inscriptions in Arabic. (See above for details on the Hebrew University expedition’s finds from the later periods on Tel Beth-Shean.)

The monasteries of Tel

At the foot of the tell, in the civic center, no initial significant change was discerned in the urban aspect of the city, apart from the continuation of the above-mentioned process consisting of the abandonment of public structures and accelerated private construction in the previously public areas. The earthquake of c. 660 CE, however, had a dramatic effect on the appearance of the city. It seems that some of the porticos of the colonnaded streets, the porticos of the agora, and that of the Sigma collapsed at this time and their ruins became a source of building stone for construction in other areas. It was only after the earthquake and as a result of the Umayyad reforms beginning in the mid-690s CE that the civic center, which until now had stood in ruin, changed its function as well as its appearance.

The center of the Umayyad city was now located on the tell, comprising mainly a crowded residential district gradually spreading into the old city center at the foot of the tell. On the saddle between the tell and the western hill, a number of buildings, which in the past were part of a residential area, were now used for light industry. The commercial area near the tell was greatly developed, attesting—along with the shops of the northwestern portico of the agora—to the extent of commercial activity in the city during the Umayyad period. The efforts expended to maintain the city gates, the bridges over

Later Arabic sources from the Abbasid and Fatimid periods mention Beisan as a small city with abundant water sources, famous mainly for its date palm groves. However, these sources relate to the period after the earthquake and therefore do not reflect the economy of the Umayyad city. From 700 CE an extensive pottery industry, which produced large quantities of ware, was located on the edges of the theater and within the area of the agora. Near the northeastern corner of the theater and even inside it was found a large complex of installations for ceramic production, including ten pottery kilns and their wide array of products. Nearby, in the area of the agora, was revealed another workshop, which included, apart from two large, two-storied buildings built around large courtyards, many installations and a large number of kilns. Found in the rooms of one of the buildings were many vessels waiting to be marketed; such vessels produced in these workshops were sold to the shops in the commercial center. The discovery of a variety of vessels from the workshops of Beisan at many other nearby sites attests to the extent of the trade and the wide distribution of these wares throughout the entire region.

Another industrial complex was built in this period within the area of the frigidarium of the eastern bathhouse, whose impressive stone dome had collapsed in the earthquake of 749 CE and sealed the complex beneath it. Within the three large marble pools of the bathhouse frigidarium, a sophisticated system of smaller pools was built, making use of the water supply and drainage systems of the bathhouse. In the adjacent frigidarium, whose dome had also collapsed, a luxurious residence was uncovered in which columns and capitals of the bathhouse were in secondary use. It probably belonged to the owners of the nearby workshop. Although there was no clear evidence indicating the products of this industry, it may have been involved in the dyeing of linen garments, as Nysa-Scythopolis was famous for its high-quality linen products. This is mentioned in the Talmud, in a Latin work of the fourth century CE (Expositio totius mundi et gentium), and in the price list of the emperor Diocletian from the end of the third century CE, which authorizes the highest prices for the products of the city. It seems that even in the Umayyad period the city continued to be a center for the spinning, weaving, and dyeing of linen garments, an industry conducted mainly by the Christian inhabitants of the city and whose products were now marketed by Muslim traders.

Not only industry was located on the outskirts of the Umayyad city. Palladius Street went out of use and agricultural terraces were probably constructed in its area. Found within the city were many flourmills, which made extensive use of the abundant water supply conveyed to the city in this period from the springs of Gilboa by the sophisticated water system constructed in the Roman-Byzantine period. While most of these flourmills date later than the Umayyad period, it is possible that some were already in use in this period, reflecting the role of Beisan as a flour-milling center for the entire region.

In the area of the Sigma, which was destroyed by the earthquake of c. 660 CE and partially dismantled, was found an Umayyad cemetery containing c. 350 graves of men, women, and children. The character of the graves and the position of the deceased indicate without a doubt that they were Muslim. The burials began around 700 CE and reflect, therefore, the change that began at this time in the function of the old civic center.

On the 18th of January 749 CE, Umayyad Beisan came to a sudden end when it was totally destroyed by a mighty earthquake. The few scattered dwellings erected over the ruins, which apparently belong to the survivors of the earthquake, are but a shadow of the city’s magnificent past. The center of the city now moved to the southern hill, where a Crusader fortress was erected with a surrounding moat (see below). During the Ottoman period a small village was located on that hill, which became the core of modern Beth-Shean in the 1950s. This splendid ancient city, as well as the evidence of its dramatic downfall, waited patiently for archaeological excavations to reveal its hidden secrets.

GABI MAZOR

THE HELLENISTIC TO EARLY ISLAMIC PERIODS AT THE FOOT OF THE MOUND: THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY EXCAVATIONS

INTRODUCTION