Beth-Shemesh

THE RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

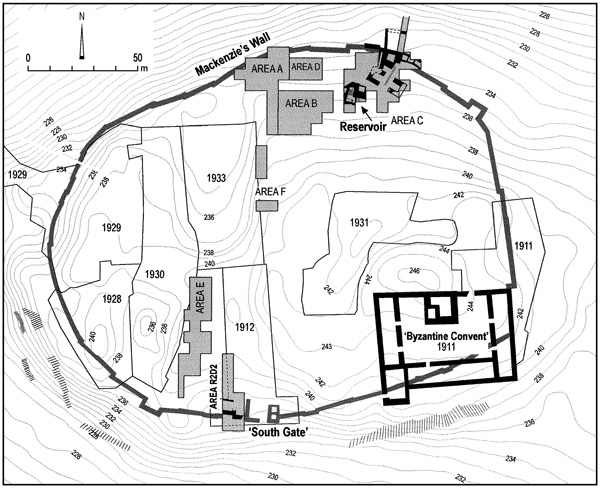

The renewed excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh began in 1990 under the direction of S. Bunimovitz and Z. Lederman. The 1990–1996 excavations were conducted on behalf of the Department of Land of Israel Studies at Bar-Ilan University; from 1995–1996 they were in collaboration with the Department of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. From 1996 the expedition has collaborated with S. Weitzman of Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, and from 1997 it has been under the auspices of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University.

In 12 seasons of excavation, 2,600 sq m were excavated in seven areas (A–F, R2D2). The excavations concentrated mainly on the Iron Age levels; yet, in one area (R2D2), Middle Bronze Age remains were exposed in situ. The renewed excavations established the following Iron Age stratigraphy at the site:

- Level 6: Iron Age I, 1150–1100 BCE (E. Grant and G. E. Wright’s stratum III).

- Level 5: Iron Age I, 1100–1050 BCE (Grant and Wright’s stratum III).

- Level 4: Iron Age I, 1050–950 BCE (Grant and Wright’s stratum IIa).

- Level 3: Iron Age IIA, 950–750 BCE (Grant and Wright’s stratum IIb/IIc).

- Level 2: Iron Age IIB, 750–701 BCE (Grant and Wright’s stratum IIc).

- Level 1: Iron Age IIC, 650–635 BCE.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE WALL. At the lower tip of area R2D2, on the steep southern slope of the mound, a massive stone wall was exposed. The wall, about 2 m wide, is built of medium to large fieldstones and was founded within a shallow trench cut in the chalky bedrock. The segment exposed was built in saw-tooth fashion and must have supported a brick superstructure; a mass of burnt and fallen bricks was found lying in front of it. No traces of additional defensive elements such as an earth or chalk glacis were found. A room was excavated behind the wall, its earth floor laid directly on the flattened bedrock. On the floor were two ovens (tabuns). The pottery retrieved from the room is predominately Middle Bronze Age IIB. Since the wall segment seems to be part of D. Mackenzie’s Strong Wall, which encircles the entire mound (now completely covered and unseen), one may conclude from the excavation of this room that Beth-Shemesh was first defended by a city wall in the Middle Bronze Age IIB. Presumably, Mackenzie’s South Gate, located near the newly found segment of the Strong Wall, should also be dated to that period.

THE IRON AGE I (LEVELS 6–4). Iron Age I remains were unearthed in all areas of the new excavations. So far, three phases of unfortified occupation (levels 6–4) were discerned, dating from the mid-twelfth century BCE to the establishment of the first Iron Age II city (level 3) in the second half of the tenth century BCE. Substantial remains of levels 6 and 4, the main Iron Age I phases, were excavated mainly at the north of the mound in areas A, C, and D. Level 5 designates sparse remains of a short-lived phase found mainly in area A.

In level 6, the earliest phase of the Iron Age I, two contiguous, spacious buildings were exposed in areas A and D, both destroyed in a fierce conflagration. Since the buildings have doorways opening towards the mound’s slope and there are wall stumps in that direction, it is apparent that a row of lateral rooms originally lay in front of the existing remains. The two buildings seem, therefore, to comprise the remains of a contiguous stretch of buildings lying along the fringe of the mound. The western building, dubbed the “patrician house,” is the more impressive. It consists of two elongated halls, one beautifully paved in large pebbles, on both sides of an inner court or large room. The massive stone walls are indicative of the existence of an upper story, confirmed by the mass of fallen mud bricks that sealed the ground floor. Some gold jewelry found within the debris had apparently fallen from above. One of the walls contained in its foundations a lamp and bowl deposit. The building east of the “patrician house” is similarly planned though of poorer construction. A few installations found in its rooms, such as a large grinding stone and hearths, reflect the daily life of its inhabitants. Found near the hearth in one of the rooms was a large flat stone that probably served as a base for a wooden column. A row of four similar column bases, contemporaneous with the “patrician house,” was also found in area A. The use of wooden columns in the early Iron Age I buildings at Beth-Shemesh represents a Canaanite architectural tradition. Similar architecture appears at Late Bronze/Iron Age I sites in the Shephelah, such as Tel Batash, Tel

In accordance with the architecture, the character and composition of the pottery assemblage from level 6 shows clear affinities with other lowland sites such as Tel Batash, Gezer, and Tell Qasile. On the other hand, it is noticeably different from contemporary assemblages at the so-called Proto-Israelite sites in the hill country. Monochrome Philistine pottery (Mycenean IIIC1) is so far missing at Beth-Shemesh, as are other cultural traits typical of the first phase of Philistine settlement in Canaan. The amount of Philistine bichrome pottery found in the early Iron I levels is surprisingly small, comprising only five percent of the relevant ceramic assemblage.

Relying on architecture and pottery, the material culture of Beth-Shemesh certainly reflects a continuation of Canaanite cultural traditions until the end of the twelfth century BCE and beyond. Yet food remains at the site reveal a more complicated situation. Analysis of over 6,000 animal bones from the early Iron Age I levels proves that pork was entirely avoided at Beth-Shemesh, in contrast with contemporary Philistine centers (at which there is evidence of 18–19 percent pork consumption) and Late Bronze Canaanite sites in the Shephelah (with 5–8 percent), yet consistent with the minimal percentage of pig bones at the Proto-Israelite sites. The remains at Beth-Shemesh are interpreted as reflecting the establishment of ethnic boundaries following the Philistine settlement in the Shephelah. It is suggested that Philistine expansion north and east of their original enclave in the Coastal Plain initiated competition and struggle over natural resources in the Sorek Valley. This in turn prompted the indigenous population of the valley to establish social and cultural boundaries to distinguish itself from its new aggressive neighbors. One such conspicuous boundary, evident at Beth-Shemesh, could have been pork avoidance, in its contrasting of Philistine eating habits. Conceivably, under continuous Philistine pressure, the pork taboo could have become a shared cultural value of the various groups settled in the mountain region and its periphery, eventually turning into an Israelite ethnic marker.

As mentioned above, level 5 is a short-lived occupational phase sandwiched between levels 6 and 4. It includes a squatter phase above the “patrician house” and a variety of other fragmentary Iron Age I occupational remains stratified over level 6 in area A.

Level 4 is the latest Iron Age I occupation phase at Beth-Shemesh, characterized by the first extensive use of monolithic stone pillars for roofing support. This phase was severely disturbed by large-scale building operations that took place in level 3, when the Iron Age I unfortified village/town of Beth-Shemesh was transformed into a royal administrative center. The level 4 remains are domestic in nature, consisting of fragmentary houses in areas A and C with monolithic stone pillars set within chalk floors, tabuns, and domestic contents. Many square- or cigar-shaped pillars were found integrated within public buildings of level 3, apparently in secondary use (see below). Of special interest in area C are the remains of a house separated by an alley from an adjacent industrial installation (of an undetermined function). The installation and the alley were deliberately filled and became obsolete when the entrance complex for the underground water reservoir of level 3 was constructed (see below). The pottery assemblage of level 4 belongs to the very end of the Iron Age I or beginning of the Iron Age II. Level 4 represents, therefore, a stratigraphic/ceramic horizon antedating the construction of the first monumental buildings at the site.

THE IRON AGE IIa (LEVEL 3). Level 3 is the main Iron Age II level exposed at the site. It is a lengthy phase, dating from the second half of the tenth century to the first half of the eighth century BCE, and including the transformation of Beth-Shemesh into a royal administrative center on the border between Judah and Philistia, its peaceful development, and its violent destruction. The level is characterized by a great variety of public buildings constructed immediately over structures of level 4 and incorporating building materials robbed from that level. The distribution of the public buildings over the entire site and their functional character leaves no doubt that the central government was involved in the replanning of the town. The insights gained by the study of level 3 have a bearing on the much-debated issue of the emergence of the state in Judah.

The Iron Age fortifications of Beth-Shemesh were investigated mainly in area C. A deep section cut down the mound’s slope exposed a large revetment tower constructed on bedrock and supporting a massive city wall built further up the slope, the impressive corner of which has been exposed. It is built of large fieldstones founded on huge boulders and was preserved in parts to a height of over 2 m. The flat upper courses of the walls indicate that they carried a massive mud-brick superstructure. A paved and partially roofed secret passage discovered next to a “saw-tooth” in the wall led out from the city to the northern slope of the mound. Three casemates were found abutting the wall’s massive corner. Probes under the corner of the fortifications down to bedrock found no evidence of earlier fortifications. The pottery found in the foundations of the fortifications indicates that they were constructed in the second half of the tenth century BCE.

The large public structure uncovered in area B, measuring more than 15 by 15 m, has massive mud-brick walls on stone foundations. Two building phases are evident. In the later, the building reached its enlarged, final state, with two main broad halls, each divided into two elongated spaces by a row of pillar bases (broken cigar-shaped pillars from level 4). The northern hall has a thick plaster floor while that of the southern is stone-paved. The plan of the building is similar to the governor’s residence exposed by E. Grant in the western quarter of Beth-Shemesh. It yielded very few finds, and was probably evacuated before it burned down.

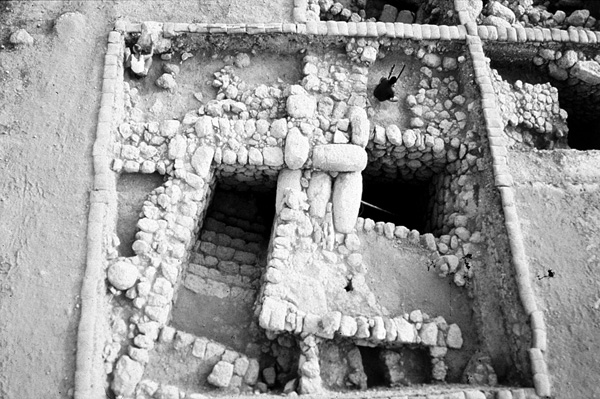

The most impressive public project of level 3 is the underground water reservoir. The cruciform reservoir consists of a central area and four rectangular halls. Its total volume is c. 800 cu m. The four halls were originally identical in size (c. 9 m long, 4 m wide, 6 m high). Later, however, two were reduced in width by an additional plastered construction, presumably built in order to raise the water level. The walls and floors of the reservoir were plastered three times. The first layer consists of thick (10 cm) cement-like chalky plaster; the second layer is thinner (2 cm); the third layer (2 cm) was applied only to the floors of the halls and the lower part of the walls to slightly above height of a standing person. This final modification was carried out by hand, leaving handprints in the plaster.

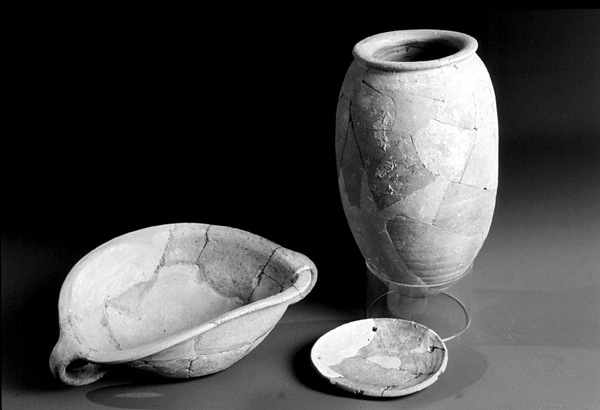

Water was drawn from the reservoir through a round shaft descending vertically from the mound’s surface to the reservoir’s central area. Maintenance operations, however, were presumably carried out through an entrance structure and a stairway leading down into the northwestern hall reservoir. In order to construct the stairway, a large square shaft was dug to bedrock, supported by retaining walls. On the eastern side of the shaft a massive pier adjoins the stairs. The stairway leading to the reservoir is comprised of three segments. Only four steps of the upper staircase survive. The intermediary staircase consists of seven broad steps, built with flat fieldstones. The steps, retaining walls, and pier there were plastered in order to facilitate the flow of surface run-off into the reservoir. A plastered channel leads from the city through the pier and down the steps. Additional segments of plastered channels, near the reservoir’s entrance structure and further away, indicate that the reservoir was fed by rainwater collected from the entire northeastern part of the mound. At the bottom of the intermediary staircase is the most impressive part of the entrance system: a narrow passage between the central pier and the shaft’s retaining wall, roofed by three cigar-shaped stones, each weighing over half a ton. The retaining wall at this point is also imposing, with its large, dressed headers and stretchers. Below this passage, the lowest staircase descends sharply to the hewn mouth of the reservoir. The lowest part of the shaft is rock hewn and plastered; a vaulted opening in its eastern side leads into the reservoir; and a bench was left hewn in the rock under the vaulted opening, where vessels for the drawing of water could be placed. Two jars and a globular cooking pot, left by their owners, were discovered in situ on this bench.

Investigation of the entrance structure showed that its walls were established directly on the remains of level 4, the latest Iron Age I occupation layer. The level 4 house floors cut by these walls bore pottery assemblages identical to those retrieved from the foundations of the fortifications. Both the fortifications and the water reservoir seem therefore to be related to the intervention of the early monarchy at Beth-Shemesh.

Intriguing remains of public character were also exposed in area E, at the southern part of the site. Here, a large chalk-paved open area was found to be covered by a mass of fallen bricks fired red in a heavy conflagration. The area is located between two substantial public buildings: one is a tripartite storehouse excavated by E. Grant at the southeast corner of his 1930 trench, the other is a large building of which only the massive west wall escaped later disturbances. The function of the open area could be inferred from the restorable pottery found smashed and scattered all over it. The vessels are limited in variety and consist mainly of small hole-mouth jars and scoops, though storage jars and large pithoi were also retrieved. There was no clue as to the commodities stored within them. A small clay scale-pan indicates economic transactions of some sort. The open area and its vicinity were therefore dubbed a “commercial area.”

North of the “commercial area” and immediately adjacent to Grant’s 1930 trench, a stone building of the same phase was exposed. Only a few of the building’s rooms escaped later disturbances; they attest to a violent destruction. A row of 11 lamelekh-like storage jars and a large pithos were found in situ. Close to the jars an assemblage of small pottery vessels was exposed, including a wine set that contains a jug, a strainer, and deep bowls. A rich pottery assemblage was also found on the floor of an adjacent room. A typological study places it in the first half of the eighth century BCE.

An important discovery in area E is an iron workshop unearthed under the chalk floor of the “commercial area,” which indicates that the public function of that area goes back to the beginning of the Iron Age II. Stratigraphical evidence attests that the workshop had an earlier phase, still to be investigated in detail. The workshop, which extended across an open area next to the remains of a large public building (almost entirely disturbed), feature several pits used as smithing hearths. Iron smithing related materials—charcoal, block tuyeres (square in section), and a large amount of slag, the bulk of which consists of concavo-convex smith hearth bottoms—were found within and around the hearths. Magnetic tracing of hammerscale distribution in the workshop also attests to iron working around the smithing hearths. Some finished iron artifacts (arrowheads, a plowshare, blades, etc.) may have been manufactured or repaired in the smithy. The finds from the workshop are currently under analysis in collaboration with T. Rehern of the Institute of Archaeology, University College, London.

The iron workshop of Beth-Shemesh is the earliest excavated in the Near East. Dating to the ninth century BCE, it spans the crucial years when the technological and cultural transition from bronze to iron was completed and iron became commonly utilized. The close spatial and contextual relations between the earliest Iron Age II public buildings in area E and the iron workshop raise intriguing questions about the connection between the adoption of iron into general use and the moving of Israelite society toward statehood. The finds at Beth-Shemesh suggest that social and political centralization in the tenth–ninth centuries BCE in Judah were accompanied by the appropriation and control of iron technology, given its growing economic importance.

Private houses of level 3 were excavated in areas B, F, and E. In area B, houses contiguous with the main public building have round stone mortars set within packed earthen floors. In area E, square stone monoliths were found integrated within the fieldstone walls of the houses. The same architectural elements characterize the Iron Age II remains excavated by E. Grant. Of special importance is a spacious building excavated in area F, which presents a series of floors spanning the lifetime of level 3 and attesting to its peaceful nature. The last phase of the house contains a large olive crushing basin indicating that the olive-oil industry at Beth-Shemesh, which is typical mainly to level 2, already began in level 3.

The longevity of level 3 is reflected in its pottery assemblage, which shows that the first public enterprises at Beth-Shemesh took place already in the second half of the tenth century BCE. The fierce destruction that ended level 3 can be explained by a number of possible historical scenarios. Yet it must be emphasized that the destruction occurred prior to Sennacherib’s campaign in Judah, presumably during the first half of the eighth century BCE. The bulk of level 3 pottery suggests decades of ordinary, quiet daily life, with no evidence of momentous events, which would have left behind shattered ceramic clusters in situ. The pottery spans the construction and destruction assemblages of level 3 and is found mainly in constructional fills of levels 3–2 all over the excavated area (an important exception is the vessels comprising the wine set mentioned above).

Noteworthy among the finds of level 3 is a piece of a double-sided game board. On its narrow side the name of its owner,

The importance of Tel Beth-Shemesh for understanding the transition in Judah from rural to monarchic society lies not only in its continuous settlement sequence but in the extent of the excavations conducted at the site. In the three cycles of excavations at Beth-Shemesh, large tracts of the site were exposed, affording an almost complete view of an Iron Age town with all its functional details. An integrated map of the site, produced for the first time by the present expedition, allows a coherent view of the Iron Age settlements covering the whole site. Focusing on the level 3 town plan, the new map highlights the governmental symbols that transformed the character of rural Beth-Shemesh. These include: fortifications and the underground water reservoir in area C; the public building in area B; the governor’s residence (most probably a double storehouse), the huge silo, and another storehouse in the 1928–1930 excavation trenches of E. Grant; and a “commercial area” replacing an earlier public iron workshop in area E.

THE IRON AGE IIb (LEVEL 2). Level 2 is the last extensive Iron Age settlement at Tel Beth-Shemesh, destroyed by Sennacherib’s army in 701 BCE. No evidence of an Iron Age settlement later than the eighth century BCE was uncovered above level 2 (for the limited episode of level 1, see below). Being the uppermost level of the mound (D. Mackenzie’s Byzantine Convent and the adjacent medieval Arabic huts are concentrated on the east side of the site), it suffered heavily from a variety of post-depositional processes. Though much level 2 pottery was found on the surface and in sub-surface layers of all areas excavated, only a few pockets were actually in situ and restorable. At any event, the pottery assemblage of level 2 is typical of the Lachish III horizon and includes 21 lamelekh (double-winged and four-winged) and four official (“private”) seal impressions. The conclusion that level 2 was destroyed and abandoned in 701 BCE concurs with D. Mackenzie’s opinion and is supported by an examination of the pottery assemblage from E. Grant’s excavation. The 586 BCE date suggested by E. Grant and G. E. Wright for the destruction of their stratum IIc should be understood today as reflecting W. F. Albright’s erroneous interpretation of the late Iron Age levels at Tell Beit Mirsim.

A few structures exposed in areas A, B, F, and E contained the remains of olive-oil press installations: monolithic crushing basins, vat presses, stone weights, plastered or paved floors with hole-mouth jars sunken in them, plastered cells for keeping the produce, and scores of carbonized olive pits strewn all over the remains. In area E, a large number of hole-mouth jars was found around the olive-oil installation. Notably, in his nearby 1912 excavations, D. Mackenzie exposed an olive-oil installation, including presses and some intact hole-mouth jars of the same kind. He also found many sherds of such vessels scattered around the installation. It seems, therefore, that in the second half of the eighth century BCE a number of olive-oil installations existed in the southern quarter of the town, as well as in the northern and central quarters. Since more olive-oil installations were exposed by E. Grant all over his excavation plots, it is apparent that the production of olive oil, which already began in level 3, was an important component in the economy of Beth-Shemesh on the eve of Sennacherib’s campaign. This industry came to an end in 701 BCE when the town was abandoned and parts of the Shephelah of Judah, including olive groves, were given to the Philistine city-states by the Assyrians (see below).

Remains of private houses exposed in area E consist mainly of fieldstone walls integrating square stone monoliths, and pebble or plaster floors. In the destruction layer of one of the houses, a bowl bearing the chiseled inscription qds was found. Similar bowls are known from Judah, especially in the eighth century BCE, and were interpreted as denoting offerings taken by priests to their homes.

The fortification complex of level 3 seems to have fallen out of use in level 2, when a structure oriented in a different direction and resembling a two-chambered gate was built above it. Since no adjoining wall was found (see below), the function of the structure as a gate is questionable. Due to its proximity to the surface, the structure was severely damaged and only its foundations were preserved, and only partially. The construction of the foundations is not uniform: two of the piers incorporate reused cigar-shaped columns, while the other two make use of rectangular ashlars. The leveled top of the foundations suggests that they had carried a brick superstructure. The foundations of the structure’s chambers, as well as supporting walls linking them, were built within a large pit dug into earlier strata. Constructional fill was then carefully laid between the piers and around them. A plastered channel roofed with large, flat fieldstones, of which only a few survived, was uncovered in the passage between the structure’s chambers. The channel, whose northern part had eroded down the slope, was built together with the structure’s foundations and was integrated into the supporting walls and fills. An outlet of this channel was revealed close to the ceiling of the underground water reservoir’s northwestern hall. It is conceivable that the channel collected rainwater from the periphery of the site into the reservoir. Alternatively, it might have let surplus water out of the reservoir. A large plastered plaza was uncovered behind the structure. It seems to have been connected with its superstructure, thus covering the passage and the water channel. This so-called gate lacks an accompanying wall and presumably was part of the water reservoir complex. Both previous excavators of Beth-Shemesh have noted the absence of fortifications at the last Iron Age II town of Beth-Shemesh and the spread of houses above and beyond the line of the former city wall. The new excavations seem to confirm this observation.

The modest and probably unfortified town of level 2 appears to reflect expansionist trends of the kings of Judah in the eighth century BCE. In light of the complete destruction of level 3 at Beth-Shemesh and the sudden reconstituting of a fortified town culturally oriented towards Judah at the long abandoned neighboring site of Tel Batash/Timnah, it is conceivable that Judah’s border with Philistia was moved west, leaving Beth-Shemesh behind.

THE IRON AGE IIC (LEVEL 1). The renewed excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh made clear that the city was finally destroyed and abandoned in 701 BCE. D. Mackenzie’s claim for a transitory reoccupation phase after Sennacherib’s campaign should be interpreted as referring to the fragmentary remains of level 2 overlying the major destruction of level 3, which he erroneously related to Sennacherib. However, unexpectedly, excavations in the underground water reservoir have shed light on a short and unsuccessful attempt to return to the desolate site. In the silt layer accumulated on the reservoir’s floor, a few complete jugs and hole-mouth jars as well as many broken jugs typical of the seventh century BCE were found. These containers were used for drawing water and represent resumption of use of the reservoir after its cleaning and partial replastering. Shortly after its reactivation, however, the steps descending into the reservoir were completely blocked by massive earthen fill (weighing c. 150 tons). Removal of the dump showed that it is comprised of habitation remains, mainly of level 2, which were deliberately thrown into the steps’ shaft. Apparently, it was intended to prevent access to the primary source of water of the site.

This previously unknown episode in the history of Beth-Shemesh is interpreted in light of the geopolitical situation in the Shephelah following Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 BCE. As a result of this campaign, the Shephelah of Judah was devastated and depopulated. Moreover, Sennacherib awarded parts of the region to the Philistine kings not only as a means of castigating the rebellious Judah, but as part of a calculated policy that encouraged the economic growth of Philistia. It is likely that the olive groves and wheat fields around Beth-Shemesh were controlled by Ekron (Tel Miqne), which became one of the largest olive oil producing centers in the Levant. For decades, the people of Judah could not return to their land, which was cultivated by others. According to the pottery analysis, a small group from Judah tried to return to Beth-Shemesh between 650–635 BCE. The new discoveries suggest that they reactivated the desolated water reservoir and settled around it. However, the Philistines and their Assyrian overlords reacted violently and sealed the water source of the site, and the site never recovered.

SHLOMO BUNIMOVITZ, ZVI LEDERMAN

THE RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

The renewed excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh began in 1990 under the direction of S. Bunimovitz and Z. Lederman. The 1990–1996 excavations were conducted on behalf of the Department of Land of Israel Studies at Bar-Ilan University; from 1995–1996 they were in collaboration with the Department of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. From 1996 the expedition has collaborated with S. Weitzman of Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, and from 1997 it has been under the auspices of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University.

In 12 seasons of excavation, 2,600 sq m were excavated in seven areas (A–F, R2D2). The excavations concentrated mainly on the Iron Age levels; yet, in one area (R2D2), Middle Bronze Age remains were exposed in situ. The renewed excavations established the following Iron Age stratigraphy at the site: