Bethsaida (et-Tell)

THE SITE

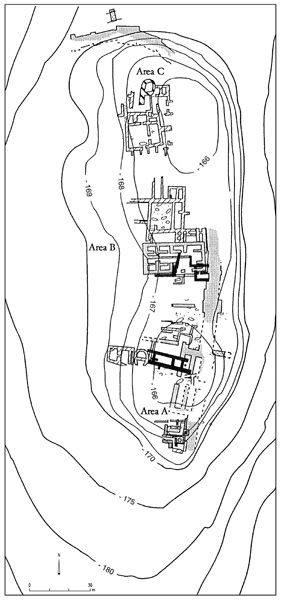

Bethsaida lies northeast of the Sea of Galilee, 1.5 km from the present-day shoreline and several hundred meters east of the Jordan River. It is identified with a 20-a. mound known as et-Tell, which rises to an elevation of 45 m above a plain known as the Bethsaida Plain (or Bateiha Plain). Geological investigations in the Bethsaida Plain have revealed that it was formed over the past 2,000 years. Prior to that, the Sea of Galilee reached the southern slopes of the mound. As a result of earthquakes and landslides, the Jordan River was blocked, resulting in its overflow and the formation of silt beds along its banks. This ultimately resulted in the uplifting of the plain above the banks of the river and the shoreline. At the end of this process, the shoreline of the lake retreated southward. Today’s shoreline is located 1.5 km from the mound.

IDENTIFICATION

The wealth and character of its Iron Age remains suggest that Bethsaida was the capital of the kingdom of Geshur during the tenth–ninth centuries BCE. It may reasonably be assumed that the name of the site during the Iron Age was Tzer or Tzed, if the interpretation of the enigmatic verse Jos. 19:35 is correct.

Bethsaida is mentioned frequently in the New Testament as the birthplace of three of the Apostles—Peter, Andrew, and Philip—and as a center of Jesus’ ministry. Byzantine sources indicate that the Zebedee brothers, James and John, came from Bethsaida. Near Bethsaida, Jesus healed a blind man (Mk. 8:22), performed the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes (Lk. 9:11), and was seen walking on the sea (Mk. 6:45). According to Matthew and Luke (Q sources), Jesus rebuked the cities of Bethsaida, Chorazin, and Capernaum for refusing to repent.

Josephus locates Bethsaida in lower Gaulanitis, near the estuary of the Jordan River. He states that Philip, the son of Herod the Great, who inherited Gaulanitis from his father, elevated the village of Bethsaida to the status of a Greek city (polis) and renamed it Julias. Eusebius’ Chronicles state that Julias was founded during the reign of Tiberius, a view rejected by E. Schuerer. However, numismatic and archaeological evidence have provided support for Eusebius’ claim and date the renaming to 30 CE. Julias was named after Julia/Livia, wife of the emperor Augustus and mother of Tiberius. She had died a few months earlier and Philip renamed the city to honor the Roman imperial cult. Remains of a small temple discovered at the site are attributed to this program. Josephus recounted that one of the early skirmishes in the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (perhaps in 65 CE) took place near Julias. In this battle he was injured and evacuated to Capernaum; however, the fate of the city following this battle is not described.

Eusebius locates Bethsaida six miles from Capernaum. Bethsaida is frequently mentioned by Christian pilgrims from the fourth century CE onward. Willibald, an eighth-century German pilgrim, mentions his visit to Bethsaida and a church there dedicated to Peter. He stayed there overnight and continued to Capernaum. No Byzantine church has been discovered at Bethsaida and Willibald’s description more likely fits the octagonal church in Capernaum. Apparently, the true location of Bethsaida had been forgotten by the fourth century CE.

The search for Bethsaida was initiated during the Renaissance. Bethsaida appears on the maps of this period either west or east of the Sea of Galilee. The view that Bethsaida and Julias are two separate places was proposed by G. Schumacher in the 1880s. According to this theory, widely accepted through the twentieth century, Bethsaida should be identified with el-‘Araj, a site near the estuary of the Jordan River on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee, while Julias and the palace of Philip should be located on the mound of et-Tell. Modern archaeological surveys and research have refuted this theory. Julias and Bethsaida were indeed the same place.

Bethsaida was first identified with et-Tell, the largest mound around the Sea of Galilee, by the German traveler U. J. Seetzen in the early nineteenth century, and again in 1838 by E. Robinson, who bolstered this identification with a scrutiny of the historical sources. The French scholar V. Guérin suggested in the mid-nineteenth century that Bethsaida should be identified with Tel Hum (Capernaum). He suggested identifying Capernaum with Khirbet el-Minya (

From the late nineteenth century and until the archaeological excavations commenced in 1987, scholars tended to agree either with Robinson or Schumacher. In a field trip to the site in 1928, W. F. Albright asserted that in view of the absence of Roman pottery at et-Tell, it should not be identified with Bethsaida, suggesting instead that it had been a relatively large Middle Bronze Age city. The 1968 survey of the Golan reported sherds from the Early Bronze Age II, Middle Bronze Age I and II, Iron Age I and II, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods. However, archaeological excavations have subsequently shown that the site was uninhabited during the Middle Bronze Age. The excavations revealed sherds but no architectural remains from the Early Bronze Age I and II (the architectural remains were apparently thoroughly demolished and utilized in the construction of Iron Age earthworks), fortifications and a palace from the Iron Age IIA–B, massive Hellenistic period architectural remains unobserved in the surveys, no Byzantine or Ottoman period settlement, and only scanty finds from the Iron Age IIC, Persian, Umayyad, and Mameluke periods. Through the Ottoman period, the site served as a Bedouin cemetery.

Probes and remote sensing (ground penetration radar) near the present-day shoreline at el-‘Araj, the other contender for identification as Bethsaida, have shown it to have been an exclusively Byzantine period settlement. The finds at et-Tell support Robinson’s proposal that Bethsaida should be identified with it.

EXCAVATIONS

The excavations at Bethsaida began in 1987 under the direction of R. Arav. Between 1987–1990, the excavations were carried out on behalf of the Golan Research Institute under the auspices of Haifa University. Since 1991, they have been conducted on behalf of the Consortium for the Bethsaida Excavations Project, consisting of 24 universities and colleges headed by the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The project includes archaeological, geographical, and geological surveys on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee, aimed at reconstructing the environment and landscapes in ancient times.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

Excavations were carried out in three areas and six main strata were discerned, summarized in the following table:

| Stratum | Construction | Period | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bedouin tombs, simple structures, a modern Syrian military position | Modern | From the 16th century |

| 2 | A rural settlement surrounded by Iron Age and Roman city walls, Roman temple | Hellenistic, Roman | 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE |

| 3 | Little construction, Iron Age buildings in secondary use | Persian | 6th century BCE to 3rd century BCE |

| 4 | Little construction, Iron Age buildings in secondary use | Assyrian conquest and Babylonian period | 732 BCE to the 6th century BCE |

| 5 a, b | A thriving city, thick city walls, palace in secondary use, four-chamber city gate, granary | Iron Age IIB | 850–732 BCE |

| 6 a, b | The foundation of a thriving city, thick walls, bit hilani palace, city gate, granaries | Iron Age IIA | 950–850 BCE |

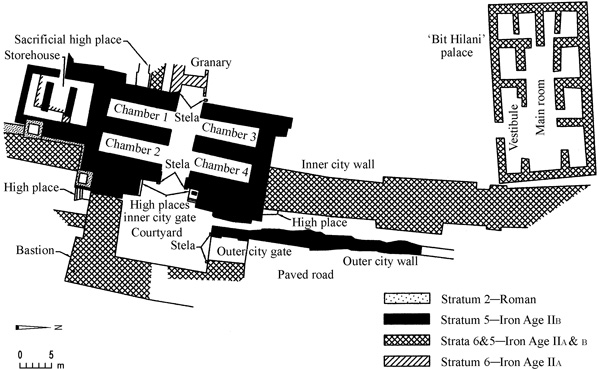

THE IRON AGE. The Iron Age remains of the site include a city gate, thick city walls, a palace in the bit hilani style, and granaries.

Area A—The City Gate. The mound on which the city was founded was originally a basalt extension descending from the Golan plateau and consisting mainly of very large boulders. The founders of the settlement erected a series of terraces, one atop the other, covering the boulders. At the top of the terraces they built two parallel walls encircling the entire mound. Information on the nature of the outer city wall in stratum 6 is still lacking. The inner city wall was constructed with offsets and insets. The core of the wall was filled with stones of various sizes. The outer face and particularly the corners were reinforced by large, meticulously laid boulders. The respective offsets and insets of the inner and outer faces of the inner city wall were parallel to each other. At the offsets, the wall attained a maximal width of 8 m; at the insets it was only 6 m wide.

At the center of the eastern side of the city, atop the series of terraces, a monumental city gate was constructed. A beaten earth road ascended to the gate from the northeast along a moderate slope. The complete plan of the gate complex is not yet clear, but there appears to have been an inner and outer gate with a courtyard between them. The outer gate was a simple structure consisting of a room 7.5 by 5.9 m with two parallel entrances. A wall of yet undetermined width connects the outer city gate with an external bastion projecting toward the eastern slope, referred to as the eastern bastion, which is in a poor state of preservation. Only its western corner was preserved, to an elevation of about 2 m. This corner was constructed with particularly large, roughly dressed stones. The area between the outer and the inner gates was paved with medium-sized cobbles, with small stones filling the gaps between them. A thick layer of white plaster covered the pavement.

At a later stage, the gate was damaged, a thick layer of debris covered the floor, and a new floor was laid on top of it. The old walls were utilized for the renewal of the gate. Stratum 6 came to an end during the ninth century BCE, in a vast destruction by a major conflagration that created a c. 1-m layer of debris. The walls evidently did not go entirely out of use, but were reused with alterations in stratum 5.

The city gate of stratum 5 was built upon the ruins of the previous stratum. Except for the eastern section, which retains the plan of the earlier city gate, there was a new plan for the gate complex. The road that led to the city was elevated and paved with carefully laid cobblestones. This pavement extends at least 50 m beyond the outer city gate. The outer city wall was rebuilt, its width varying between 1.5 and 2.5 m; it was clearly lower than the inner city wall. The area between the two walls was also paved with cobbles. The paved road led to the outer city gate, which was similar to the earlier stratum 6 outer city gate and was built upon its walls. Similar to that gate, the stratum 5 gate was 7.5 m wide and 5.9 m long.

Two 4-m-wide entrances led to a 150-sq-m paved courtyard. The courtyard was meticulously paved with fieldstones, and the view from the courtyard was completely blocked by walls and the gate structures. The wall of undetermined width that connected the bastion to the outer city gate remained in use during this time. Nothing from the bastion in stratum 5 was preserved. The assumption that it continued to exist during this period derives from the fact that the remains of the outer and inner city gates were found to be in use in both strata 6 and 5.

The inner city gate was of the four-chambered-gate type, 35 by 17 m and preserved to a maximum height of 3 m. It was perpendicular to the outer city gate. Two towers filled with stones, each 10 m long and 6 m wide, flanked the entrance. The outer face of the towers and in particular their corners were constructed with very large boulders. At the bottom of the towers were low stone benches. Remains of thick white plaster cover parts of the walls and indicate that plaster and white wash covered the entire structure. Two deep niches in the corners of the towers flanking the entrance each contained ritual high places. The gate threshold was built of large dressed stones that were carefully laid. Remains of an oak door were found on the floor of the gate. The gate passage was carefully paved with medium-sized fieldstones, polished by many years of pedestrian traffic. Two pairs of spacious chambers, each 10 by 3.65 m, faced each other on opposite sides of the entryway. A wall 2.5 m wide separates each of the chambers. The floor of the chambers was of beaten earth, except for that of chamber 2, which was plastered. The finds from three chambers (1, 3, and 4) leave no doubt that these chambers were utilized for storage rather than military purposes.

Chamber 1 was empty and chamber 2 served as a granary. A brick wall blocked the entrance to this chamber and grain impressions were found on its plastered floor. Remains of oak beams were also found in this chamber. Remnants of the collapsed upper story were discovered above c. 1.5 m of debris upon the lower floor; several jars were included among them. Chamber 3 contained approximately one ton of carbonized barley. Chamber 4 contained offering vessels probably associated with the high places at the gate. There were approximately 30 vessels, jars, jugs, carinated bowls, flat plates, cooking pots, and perforated cups. Carbonized grain was found in various parts of the chamber. One jug bears the inscription: “to the name of” followed by an ankh-like sign symbolizing the moon god.

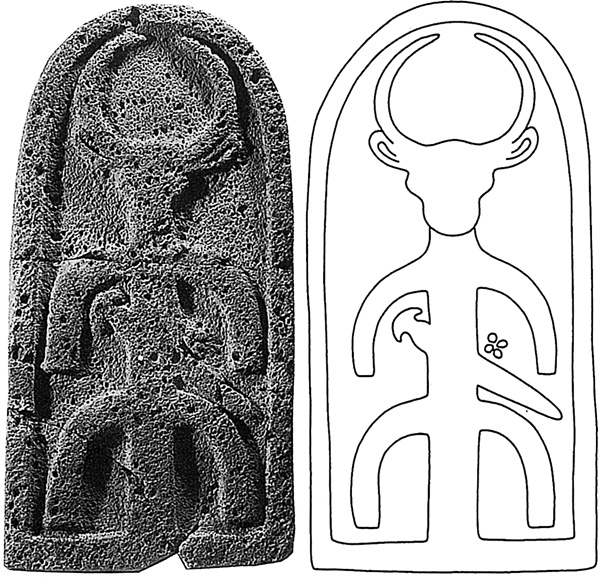

High Places and Stelae. Five high places and eight stelae were discovered in the gate complex. Five of the stelae are finely dressed, with rounded upper parts. They were found in the following locations: two in the inner courtyard near the outer city gate (in fact, only the western stela was found in situ; fragments of the eastern stela were discovered in the gate area); two dressed stelae flanking the entrance of the inner city gate; two semi-dressed stelae flanking the entrance at the back of the inner city gate; a stela in a different style in secondary use in the wall of chamber 2, which indicates that it was in use in stratum 6 of the gate; and a decorated stela on the stepped high place at the niche in the northern tower. This last stela contained two elements. The upper element is figurative and represents a bull’s head with large crescent horns. Below it is a non-figurative element consisting of a pole with two parallel arches facing down, interpreted as a Luwian hieroglyph meaning “a stela.” A dagger is located on the lower arch and a small round projection split into four portions is seen next to the dagger. Scholars identify this stela with the moon god. The stela was found shattered and scattered on top of the high place.

The five high places discovered fall into three distinct types: two were “stepped” high places, two were “direct access” high places, and one was a “sacrificial” high place. The high places were symmetrically divided between the northern and southern sections of the gate, with one “stepped” and one “direct access” high place in each section. The “sacrificial” high place was placed at the back of the inner city gate.

One of the stepped high places (1.45 by 2.7 m by c. 1 m high) was constructed in the niche of the northern tower. Built of basalt fieldstone and in a style similar to the gate complex, it was covered with white plaster. It contains two steps leading to a podium upon which the decorated stela and a rectangular basalt basin stood. Two perforated ritual cups of the type known primarily from Transjordanian Iron Age sites were found inside the basin. It seems that the cups were used for pouring libations from the basin. The stepped high place in the southern wing was built near the southern corner of the southern tower. It contained three low steps leading to an empty podium. No ritual objects or stelae were found on this high place. A wall connecting the tower to the bastion built behind the high place indicates that it was indeed a high place and not an ordinary stairway.

In the niche of the southern tower, adjacent to the entryway, was a high place of the “direct access” type. It consists of a shelf 1 m above the ground, running the entire length of the southern wall of the niche. No steps or rampart led to the shelf, hence its name. Along the western wall of the niche was a low bench of sun-dried mud brick. The second “direct access” high place was found at the northern tower in the corner between the tower and the city wall. It is a low shelf, 2.45 by 1 by c. 0.3 m high, consisting of a line of stones filled with plaster and earth. No offering or ritual vessels were found at this high place.

At the back courtyard of the inner city gate was the “sacrificial” high place. Measuring 2.75 by 2.10 m, it consisted of a paved, sloping rampart leading to a paved high place raised only 30 cm above the level of the courtyard. Two mud-brick shelves flanked the high place on both sides. Ritual objects were discovered at the high place, including a large segment of a basalt basin with elevated corners, a flat basalt slab, a large boulder with an incision of perhaps a bull, and scattered animal bones. A large repository pit, 1.35 m in diameter and c. 3 m deep, was discovered at the north end of the high place. It was filled with ash and burnt bones of animal offerings. Analysis indicates sheep, goat, cows, and a small percentage of fallow deer. It is noteworthy that all are animals conforming to regulations in Lev. 11.

At the southern part of the gate and adjacent to it was a storehouse measuring 11.5 by 9.5 m. An entrance from the west led to a spacious room that is divided into three elongated halls by partition walls. The northern hall is subdivided into two smaller chambers. The storehouse was filled with sherds of large jars that had been smashed and scattered all about the rooms prior to the collapse of the roof.

Use of the stratum 5 gate ended in a major destruction. Evidence of a fierce conflagration that melted the bricks into clinkers was found all around the gate. The upper floors collapsed into the first floor and buried it, consequently preserving it. Dozens of iron arrowheads found in the gate attest to the warfare leading to its destruction. Pottery and 14C tests indicate that this probably occurred during the 732 BCE military campaign of the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III.

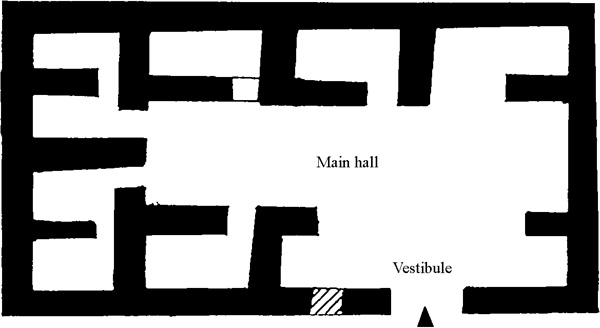

Area B—A Palace in Bit Hilani Style. A large complex associated with stratum 6 is located north of the city gate. It consists of a spacious courtyard paved with cobbles. At its northern side, a large building identified as a palace in bit hilani style was excavated. The building (28 by 15 m) was constructed of very carefully laid large basalt boulders. A wide entrance at the southern long wall, presumably without columns, led to a broad vestibule and thence to the main hall, which measured 20 by 6 m and occupied most of the structure. The hall was surrounded by eight smaller chambers. An underground tunnel connected the northeastern chamber to the area between the outer and inner city walls.

During the life span of stratum 5, a wall was built across the main hall of the palace, bisecting it into two elongated halls. It seems that during this phase the structure was no longer used as a palace. Pottery and loom weights found in the elongated halls indicate possible weaving activity on the second floor of the building.

Area C. A north–south trench was excavated in this area to examine the fortification system of the city of strata 6 and 5. Contrary to the steep slope that defended the city in the east, the northern side was much more vulnerable, and was therefore very heavily fortified; and contrary to the gate area, no evidence of an assault (such as arrowheads, catapult stones, or ash layers) was encountered in this area, which indicates that the strong fortification was effective, at least here. The fortifications included an outer city wall, c. 1–1.5 m thick, constructed of very large boulders at the bottom of a short, steep glacis. This wall was most probably lower than the much thicker inner city wall, which most plausibly served as the main component of the defenses. The glacis was supported by a massive subterranean revetment wall. A 2-m-wide terrace separated the glacis and the thick inner city wall. As in area A, the inner city wall had parallel offsets and insets on its inner and outer faces. The width of the wall varied from 6 to 8 m. At the northeastern corner of the city wall was a tower, 21 m long and 8 m wide. Two buttresses were discovered in the northern section of the city wall.

Strata 4 and 3 represent the Assyrian occupation and the Persian period. A small settlement was discerned at the site incorporating ruins and structures from the previous period. Very little was built during these periods, mostly around the ruins of the palace, which was occupied until the Hellenistic period.

THE HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN PERIODS. In spite of the differences between the stratigraphy and pottery of these two periods, most of the Hellenistic structures remained in use during the Roman period, and therefore the two are grouped together as stratum 2.

Area A. The main stratigraphical element in this period is a structure of possible Hellenistic origin. During the Roman period, this structure was transformed into a temple. Measuring 20 by 5 m, it was built atop a small mound of debris that covered the Iron Age city gate, making it the highest spot in the town and creating a podium-like structure. The eastern part of the temple was situated upon the ruins of chamber 3 of the Iron Age gate.

Many of the walls of the temple were looted in antiquity, leaving few remains of the semi-dressed basalt stones in situ. The temple included a porch, antechamber, holy of holies (naos/cella), and back porch. A few dressed stones, some with decoration, were found in secondary use in Bedouin tombs near the temple, including a lintel with a meander motif between two rosettes; a basalt jamb door containing ivy and acanthus leaves; basalt friezes depicting acanthus leaves arranged in medallions surrounding a flower; basalt columns, column drums, and bases; and a few limestone blocks and pilasters. Foundations of a column base were discovered in the area between the eastern antae.

A few figurines were found in the area of the temple, one depicting a female wearing a diadem atop cylindrical headgear covered with a veil. Another female figurine wears a veil and may depict Demeter/Ceres/Persephone/Kore, who was identified with Livia/Julia, the wife of Augustus and the mother of Tiberius, after whom Bethsaida was renamed. Other finds around the temple include a bronze incense shovel, the handle of another incense shovel and two coins minted by Philip, the son of Herod, in 30 CE. The coins commemorate the renaming of Bethsaida to Julias (which alludes to the date of the construction of the temple). To the south of the temple, a few other structures were found, some containing sherds of limestone vessels. Such vessels were, according to Jewish halakhah at the end of the Second Temple period, considered unsusceptible to ritual impurity. Their discovery in archaeological contexts thus provides evidence of a Jewish presence.

The city gate from the Iron Age was thoroughly destroyed, yet the road leading to the city gate remained in use. During the Roman period a few tombs, oriented north–south and devoid of offerings, were dug into the road. The road was covered with debris and boulders from the fourth century CE onward.

Area B. The Iron Age palace went out of use during the mid-ninth century BCE, when it was converted into a public building. Parts of it were destroyed during the Assyrian conquest of 732 BCE, but its western chambers remained in use until the Hellenistic period. During the Roman period, a private residential building was constructed atop the ruins of its eastern wing. The walls of the building abut the Iron Age city wall, which apparently remained standing. This structure contained a courtyard and three rooms in the east. It was built of medium-sized fieldstones that would have been easily transported. Its walls were c. 70 cm thick. Small stones filled the spaces between the larger ones and the entire structure was plastered. North of this building were a few more courtyard-style residential homes constructed during the Hellenistic period. The largest of these occupied 474 sq m and included a spacious paved courtyard, a kitchen on the eastern side, and residential rooms on the north. This building, like others of this period, contained a large number of fishing implements, including lead net weights, stone weights, fish hooks, and basalt anchors typical of sites around the Sea of Galilee. The anchors weigh 25–50 kg and have a hole pierced at one end.

Area C. A few residential courtyard buildings flanking a paved street were found in this area. One of the better preserved buildings contains a courtyard flanked by a kitchen on the east, which contained cooking pots, grinding stones of various types, and an oven. Among the small finds were pruning hooks and an iron house key. East of the kitchen was a small subterranean cellar covered with basalt beams. A few jars and a casserole found in the cellar indicate that it may have been used as a wine cellar. A few rooms were found on the northern side of the courtyard, one perhaps serving as a dining room. The finds, repairs, and renovations in the house indicate that the building remained in use for a lengthy period of time, perhaps starting in the Persian period (stratum 3) and continuing to the Hellenistic period. The building was possibly abandoned at the end of the second century BCE. Other houses from this period incorporated parts of the city wall, indicating that on the northern side—as on the east—the city wall remained high enough for such secondary use centuries after its construction during the Iron Age.

RAMI ARAV

Color Plates

THE SITE

Bethsaida lies northeast of the Sea of Galilee, 1.5 km from the present-day shoreline and several hundred meters east of the Jordan River. It is identified with a 20-a. mound known as et-Tell, which rises to an elevation of 45 m above a plain known as the Bethsaida Plain (or Bateiha Plain). Geological investigations in the Bethsaida Plain have revealed that it was formed over the past 2,000 years. Prior to that, the Sea of Galilee reached the southern slopes of the mound. As a result of earthquakes and landslides, the Jordan River was blocked, resulting in its overflow and the formation of silt beds along its banks. This ultimately resulted in the uplifting of the plain above the banks of the river and the shoreline. At the end of this process, the shoreline of the lake retreated southward. Today’s shoreline is located 1.5 km from the mound.

IDENTIFICATION

The wealth and character of its Iron Age remains suggest that Bethsaida was the capital of the kingdom of Geshur during the tenth–ninth centuries BCE. It may reasonably be assumed that the name of the site during the Iron Age was Tzer or Tzed, if the interpretation of the enigmatic verse Jos. 19:35 is correct.