Burj el-Aḥmar (the Red Tower)

IDENTIFICATION AND EXPLORATION

The surviving remains of Burj

Although there is archaeological evidence for the occupation of the site in the Byzantine period, the first historical reference to it occurs in 1158 CE, when Pope Hadrian IV confirmed the “tower of Latina” as belonging to the Benedictine Abbey of St. Mary Latin in Jerusalem. It was most likely granted to the abbey by the lord of Caesarea, Eustace Garnier (1105/10–1123 CE), or his son Walter (1123–1149/50 CE). The Red Tower would have been in Ayyubid hands from 1187, but when the area returned to Christian rule in 1191 it appears that the abbey, by then reestablished in Acco, leased it and its estate to the Templars. At approximately the same time, however, the abbey also leased its entire estate in the lordship of Caesarea to the Hospitallers. The resulting dispute as to which of the two military orders had the right to the Red Tower was settled in 1236, but it was not until 1248 that the Templars finally handed over the property. The Hospitallers’ lease of the Red Tower and other nearby properties was renewed in October 1267, but already by this time the area had fallen under Mameluke sway. In 1265, Sultan Baybars granted Burj

EXCAVATION RESULTS

The purpose of the excavation at Burj

PHASE A: PRE-CRUSADER, FIFTH CENTURY CE TO c. 1100/50 CE. Apart from a stone knife, possibly of the Chalcolithic period, the earliest finds were pottery and glass from the fifth century CE onward. Structures were elusive, probably because the site had been leveled prior to the construction of the tower.

PHASE B: CONSTRUCTION OF THE CRUSADER TOWER, c. 1100/50 CE. Pottery and other finds from the layers associated with the construction of the tower suggest that it was built in the first half of the twelfth century CE. It may therefore be identified as the Turris Latinae that was standing by 1158. It is uncertain, however, whether it was built by agents of the Abbey of St. Mary Latin after it came into their possession, or, as appears more probable, by the lord of Caesarea or one of his knightly tenants in an earlier phase of Frankish colonization.

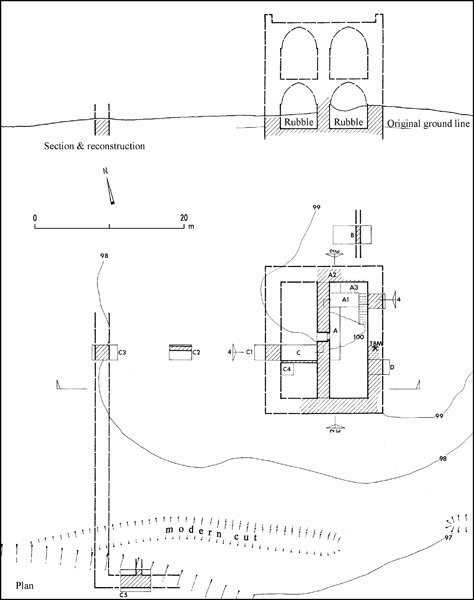

The tower was rectangular, measuring 19.7 by 15.5 m, with walls over 2 m thick. Its flat terraced roof would have been some 13 m above ground level and it was probably enclosed by a crenellated parapet. It had two stories, the lower one consisting of two barrel-vaults, side by side, and the upper apparently of six bays of groin-vaults (or cross-vaults) arranged two by three. The entrance was probably at ground-floor level on the east, though it was not found in the excavation. From the eastern basement vault, a door gave access into the western vault and a stone staircase carried on a semi-vault led up to the first floor. Trial trenches revealed the existence of an outer wall over 2 m thick, built some 21 m west of the tower. A similar wall was also found in the south, suggesting that the tower had formerly stood at the center of an enclosure measuring some 60 by 60 m.

PHASE C: OCCUPATION AFTER THE THIRD CRUSADE, c. 1191–c. 1265 CE. In a later period, probably not long before its final destruction, the interior of the tower appears to have been renovated. At the north end of the eastern ground-floor vault, a raised clay-and-plaster-covered dais was constructed over the earlier stone-flagged floor, the material filling it apparently including rubbish that had accumulated in the basement. Finds from this fill include pottery, glass, metalwork, animal bones, and some organic material. A group of 24 coins, comprising deniers of Amalric (minted 1163–c. 1219 CE) and coins of the bishopric of Le Puy, would be consistent with a date after the Third Crusade. The dais seems likely to have been a sleeping platform or mastaba, similar to those found by C. N. Johns in the suburban tower at ‘Atlit. By this period the tower may have served as the residence of an estate official who would have been installed by the Hospitallers when they took possession of the Red Tower from the Templars in 1248.

PHASE D: DESTRUCTION OF THE TOWER, c. 1265–c. 1390 CE. The tower was destroyed methodically and the lower parts of its east and west walls were partially robbed, causing them to fall outwards and the vaults to collapse. The resulting pile of rubble seems to have been picked over for building stones for some time before being leveled. The date of its destruction seems to have been around 1265, when Sultan Baybars took Caesarea and destroyed its fortifications. A terminus ante quem of 1390 was provided by Mameluke coins found lying on the leveled surface above the debris.

PHASES E AND F: LATER OCCUPATION TO FINAL ABANDONMENT IN 1947. A small settlement with houses built of mud and stone occupied the site for the next five and a half centuries. For much of this period it was possibly used only seasonally by villagers from the hills of Samaria to the east.

FINDS. The pottery from the Early Islamic, Crusader, Mameluke, and Ottoman phases includes a range of imported and locally produced wares. Although much of the metalwork and glass comes from the thirteenth-century Crusader phase, its main parallels are eastern rather than western. Analysis of the faunal remains showed that the preponderance of sheep-goat over cattle that existed in the Byzantine and Early Islamic phases gave way to an equal balance between the two in the Mameluke and Ottoman phases. In the Crusader phase, however, pig bones, which were absent in the other phases (if one excludes residual material in the later layers) account for 86 percent of the total main mammalian species, the remainder being sheep and goat. A sample of carbonized plant remains from phase D also showed, among other things, that broad beans, bread wheat, chick peas, two-row hulled barley, lentils, and grass pea were being cultivated, threshed, and cleaned in the vicinity in the thirteenth century.

DENYS PRINGLE

IDENTIFICATION AND EXPLORATION

The surviving remains of Burj

Although there is archaeological evidence for the occupation of the site in the Byzantine period, the first historical reference to it occurs in 1158 CE, when Pope Hadrian IV confirmed the “tower of Latina” as belonging to the Benedictine Abbey of St. Mary Latin in Jerusalem. It was most likely granted to the abbey by the lord of Caesarea, Eustace Garnier (1105/10–1123 CE), or his son Walter (1123–1149/50 CE). The Red Tower would have been in Ayyubid hands from 1187, but when the area returned to Christian rule in 1191 it appears that the abbey, by then reestablished in Acco, leased it and its estate to the Templars. At approximately the same time, however, the abbey also leased its entire estate in the lordship of Caesarea to the Hospitallers. The resulting dispute as to which of the two military orders had the right to the Red Tower was settled in 1236, but it was not until 1248 that the Templars finally handed over the property. The Hospitallers’ lease of the Red Tower and other nearby properties was renewed in October 1267, but already by this time the area had fallen under Mameluke sway. In 1265, Sultan Baybars granted Burj