Caesarea

THE ISRAEL ANTIQUITIES AUTHORITY EXCAVATIONS

EXCAVATIONS

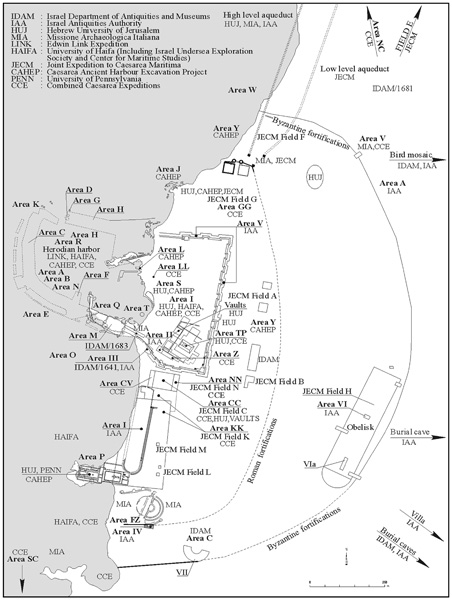

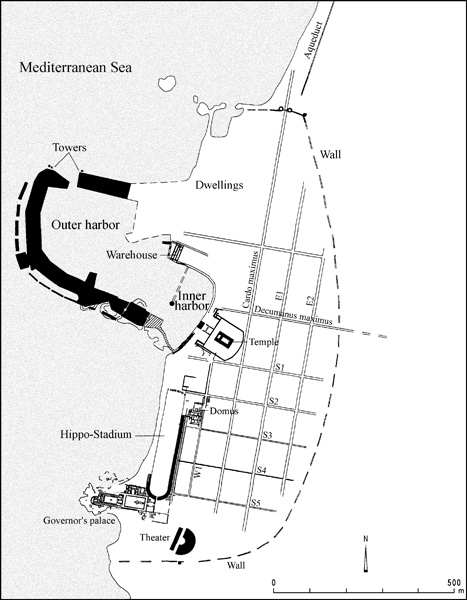

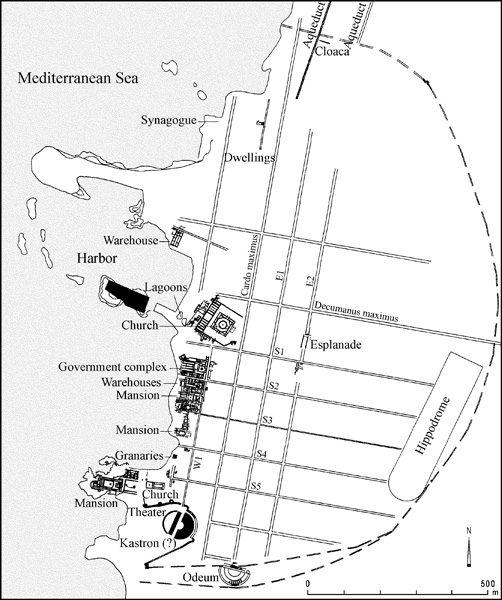

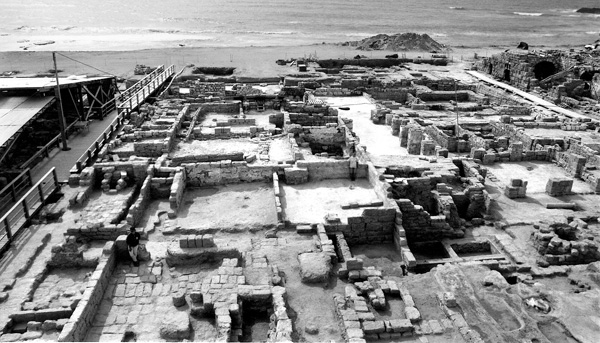

Large-scale archaeological excavations were carried out at Caesarea from 1992 to 1998 by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA); they were directed by Y. Porath. The project included the excavation of a 100–150-m-wide strip along the coast between the theater complex to the south and the excavations of the Combined Caesarea Expeditions (CCE) to the north; the western part of the temple platform and the area between this platform and the eastern quay of the port of Sebastos; both sides of the southern Crusader wall (continuing the salvage excavations carried out in 1989); the bottom of the Crusader moat (cleared in the 1960s by A. Negev), from the southern gateway to the northern gateway; and the area southwest of the theater. In addition, salvage excavations were conducted within the area demarcated by the Byzantine wall; in structures outside the wall; on the necropolis; in agricultural areas to the east, north, and south of the city; and along the aqueducts that carried water to Caesarea from outside the city.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

Fills from the Herodian period contained remains of periods predating the Hellenistic Straton’s Tower: Epipaleolithic flint artifacts, including blades and debitage, fragments of a Middle Bronze Age jar and cylindrical juglet (probably from a tomb), and numerous sherds from the end of the Iron Age and the Persian period. These sherds attest that the site was probably founded at the end of the Iron Age; however, no building remains of a settlement prior to the Hellenistic Straton’s Tower have been uncovered so far. Building remains of Straton’s Tower were discovered in excavations conducted in the northern part of the Crusader moat, indicating that the Hellenistic city did not extend as far as Caesarea’s temple platform. Cist graves in the southern necropolis of Straton’s Tower, cut into the kurkar or dug into the sand, were uncovered beneath the southern part of the Herodian city.

THE HERODIAN PERIOD: THE REIGNS OF HEROD AND ARCHELAUS. The center of the city of Caesarea, which was founded by Herod, was occupied by a temple dedicated to Roma and Augustus, erected on a platform supported by high stone walls and divided into compartments filled with earth and debris. The western walls of the platform were constructed of large kurkar stones with marginal drafting, laid as headers and stretchers. The southern wall of the platform was constructed at a right angle to the western wall, while the northern wall is at an obtuse angle (106 degrees). A paved street, perhaps the decumanus maximus, runs parallel to the northern wall. In Herodian times the western façade of the platform was without vaults and consisted of a large recessed area (c. 85 by 21 m) between two projecting wings that extended westward from the platform, creating a plaza connecting the platform and the inner harbor. A drainage channel at the western edge of the plaza carried water southward, outside the harbor area. (On the CCE’s excavation of the temple platform, see below.)

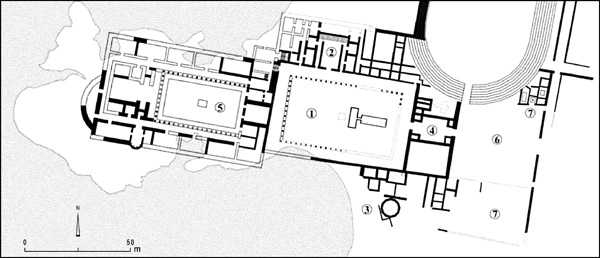

An arena for chariot racing, built like a Roman circus, was uncovered south of the harbor near the sea. The circus was found in the exact location mentioned by Josephus (Antiq. XV, 341, though he used the term amphitheatron) and dubbed “Herod’s circus” by the excavators. The western part of the circus was built on sand deposited following the construction of the artificial harbor, but this side of the structure was subsequently destroyed as a result of stone robbing as well as erosion by the sea. The original circus had an elongated U-shaped track (301 by 50.3 m) divided lengthwise through its center by a spina constructed in segments, and eight starting gates (carceres). The gates were built in a radial pattern along an arc with a radius of 55 m. Seats for the spectators were built on the eastern and southern sides only, over a fill between two walls (total width 9.25 m). The western wall of the circus (4.5 m wide) supported the fill of the track and protected it from the sea waves. The tribunal was located in the center of the eastern cavea, above a system of vaults containing concealed stairs. The circus was separated from its immediate surroundings by a deep, wide dugout (12–16 m wide and 4–6 m deep). Herodian coins found in the earliest occupational levels of the circus date its construction to the time of Herod. This facility held the chariot races during the festivities celebrating the inauguration of Caesarea (Josephus, Antiq. XVI, 137). (On the CCE’s excavation of the starting gates, and on the slightly different interpretation of the facility as a hippo-stadium, see below.)

In the area south of the theater, a segment of the southern wall of the Herodian city (1.8 m wide) was exposed. The wall and its round tower were constructed of large blocks with typical marginal drafting, and the adjacent fills contained sherds of the Herodian period. The discovery of the southern wall attests that the theater was included within the fortified limits of the city (contrary to the Italian expedition’s view), and that the northern wall with its gateway set between round towers (exposed by the Italian expedition and examined by the Joint Expedition to Caesarea Maritima, JECM, in 1978) is also to be ascribed to the earliest construction carried out by Herod. The exposed sections of the Herodian wall are located c. 560 m (3 stadia) from the temple platform, equivalent to six insulae.

THE ROMAN PERIOD. In 6 CE, the Romans replaced Herod’s son Archelaus with a Roman governor of the equestrian rank (titled praefectus and later a procurator) and made Caesarea, instead of Jerusalem, the seat of their government. The choice of Caesarea as the capital of Roman Judea led to a surge of construction in the city.

The area east of Herod’s circus was prepared for construction at the beginning of the first century CE: the surface was leveled and the dugout around the circus was filled. The fill contained a large amount of Herodian ware and numerous coins, the latest of which was struck by the governor Marcus Ambibulus (10 CE). In the leveled areas, the wealthy residents of Caesarea built luxurious mansions with walls covered in colored plaster and mosaic or plastered floors.

The area south of the circus and west of the theater was occupied by the praetorium or government compound of Judea, which continued in use until the beginning of the fourth century CE. (Another government complex with a law court was revealed by the CCE’s excavations farther north, in their areas CC and NN; see below.) In the government compound the various expeditions—Italian, Hebrew University, University of Pennsylvania, and the IAA, in chronological order—exposed the governor’s palace, several administrative offices and chambers, and the lower courses of a rectangular platform with steps between antae on the eastern side, perhaps for the Tiberium, mentioned in the inscription of Pontius Pilate.

The large and sumptuous promontory palace, 175 by 54 m at its largest, was erected on two levels along the southwestern boundary of Herod’s circus. The IAA excavated the upper level, which included a peristyle courtyard (65 by 42 m), a northern wing (65 by 22 m), a southern wing (at least 61 by 28 m), and an elaborate entry complex to the east (45 by 22 m). An open expanse on its eastern side was shared by the palace, the administrative offices to its east, and the southern entrance to the circus. The parts of the palace adjoining the circus were built on the fill of the dugout enclosing the circus from the time of Herod and Archelaus. The palace walls reaching the circus extend up to its outer wall but are not incorporated into it. In the fill beneath the early floors of the rooms in the northern wing were recovered sherds from the end of the first century BCE to the beginning of the first century CE and a coin of Archelaus.

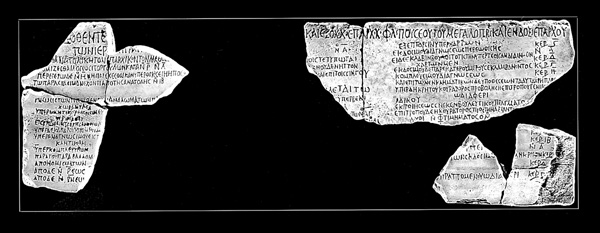

The IAA’s excavations revealed that the construction of the palace, or at least its upper level, should be ascribed to the earliest Roman governors, and not, as has been suggested by E. Netzer, B. Burrell, and K. L. Gleason, to Herod. The palace served as the seat and center of activities of the governors of Judea (named Palaestina after the suppression of the First Jewish Revolt) until the beginning of the fourth century CE. The latest dated inscriptions found in the palace are from the time of the governor Aufidius Priscus, dedicated to the co-emperors Constantius Chlorus and Galerius (293–305 CE). East of the palace were uncovered the administrative offices of the government compound with their courtyards and corridors. In two offices from the later phase of the compound, inscriptions were found in the mosaic floors, one of which mentions the offici custidiar and the other the frumentariorum.

Chariot races were held in Herod’s circus until approximately the middle of the second century CE. During the course of its existence, a cavea was added on its western side and the number of seats for spectators increased from c. 7,500 to 12,500. The floor of the arena, the stone-built spina, and the starting gates also underwent several phases of renovations (on the CCE’s excavation of the gates, see below). The filling of the dugout surrounding the initial circus allowed access to the seats from the outside, instead of from inside the arena as in the first phase. At the beginning of the first century CE the metae (turning posts) at the ends of the spina were connected to the municipal water system, but were later separated from it.

In 1996, the IAA renewed excavations along the course of the spina of the eastern circus, which replaced Herod’s circus in the middle of the second century CE. Examination of the eastern circus by the JECM in 1974 revealed that it measured 90 m wide by more than 412 m long; it is estimated that it could have accommodated more than 30,000 spectators. In the middle of the arena of the eastern circus three pieces of a broken obelisk of pink Aswan granite were found where it had fallen. Sections of the spina foundation were exposed (5.5 m wide and 1.15 m beneath the arena floor), as well as the meta prima and patches of the arena’s plaster floor. Around the obelisk the base of the spina had been widened on each side by 0.75 m, and sunken to a depth of 2.8–2.9 m below the arena surface. A solid base (c. 9 by 7 m) on which the obelisk was placed was thereby created. The obelisk was more than 14 m high and weighed over 80 tons. It was restored by the IAA and returned to its original position. An elongated euripus (water basin) lined with large marble slabs (1.5–3 m long, 1.02–1.05 m high, and 0.32–0.39 m thick) and with a white mosaic floor (c. 25 tesserae per square decimeter) crowned the spina. The euripus atop the spina terminated in the south in a semicircular recess, as in the Circus Maximus in Rome and in depictions on mosaic pavements at Carthage and Volubilis. The meta prima was exposed at the southern end of the spina. On top of it were erected three conical posts (metae) of pink Aswan granite, each consisting of two sections (total height 5.4 m, diameter 1.70–1.75 m at base and 0.32–0.35 m at top) that stood atop large marble pedestals (diameter 2.15–2.20 m), shaped like huge column bases. Three building phases could be distinguished in the meta prima; in the latest phase it was extended to fit the size of the huge conical posts. The foundation of the later phase cut through the earlier floors of the arena. The obelisk, the marble slabs lining the spina, and the conical posts on the meta prima all belong to this latest building phase. The eastern circus continued in use until the end of the Byzantine period.

After the chariot races were transferred to the eastern circus, the southern part of Herod’s circus was turned into a Roman amphitheater where gladiatorial contests (munera), hunting games (venationes), and fights between wild animals (bestearii) were staged. The floor of the arena was dug 0.5 m below the floor of Herod’s circus and the bare wall was plastered and decorated with frescoes. The plaster and drawings required frequent repair because of their exposure to the elements and proximity to the sea, and were changed due to changes in artistic taste. The earliest frescoes contained various animals drawn to different scales against a background of schematically rendered flora. Among the animals appear the lower limbs of a man walking, probably an animal tamer or a gladiator. The subsequent fresco presented imitations of colored marble panels that were later replaced by colored plaster with a red stripe. The latest plaster layer was not in color.

In the third century CE, the amphitheater occupying the southern section of Herod’s circus was no longer in use. The entire facility was later put into operation once more for a short time as an arena for chariot races, apparently during the renovation of the eastern circus (when the obelisk was erected and the spina reshaped). A new meta prima was constructed in this phase, with foundations made of drums of kurkar columns in secondary use sunk into the plastered floor of the previous amphitheater. It seems that the latest phase of the caceres belongs to the same period. The latest coin found in the arena surface of that provisional circus dates to the Emperor Alexander Severus (222–235 CE), indicating that the transition was not carried out before the Severan dynasty.

Toward the end of the first century CE, the square in front of the western façade of the temple platform was paved with stone slabs; the latest coin found in the fill below the pavement dates to the time of Titus (79–81 CE). A nymphaeum with three arched niches was added to the western façade of the northern projecting wing bordering the square. The channels for the pipes of the nymphaeum’s fountains and the niches were carved into the Herodian wall, with no regard for the joints between the blocks of the original construction, and the basin that collected the fountain’s water was built next to it. The statues found on the site—one in A. Negev’s excavations and one in the IAA’s—probably came from the niches that had decorated the nymphaeum.

It seems that the network of streets in the southwest was planned in the Herodian period, and their course remained unchanged until the end of the Byzantine period. The early streets were paved with a layer of crushed kurkar; during the second and third centuries with dolomitic limestone; and in the Byzantine period with kurkar stones mixed with reused dolomitic limestone. Lead or clay pipes laid beneath the streets carried water from the high-level aqueduct. A network of drainage channels was dug to receive rainwater and excess water from the municipal water system. (See below further discussion on the streets and their network in light of the CCE’s excavations in their areas CC, KK, and NN.)

During the first century CE the round tower of the southern wall was replaced with a rectangular tower, and a wall was built along a course that reduced the area of the fortified city. These were probably constructed at the end of 66 or beginning of 67 CE, after the annihilation of the Jewish community and as protection from raids carried out by the rebels against the gentile cities, including Caesarea (Josephus, War II, 259). Parallel to the course of the new wall, a lead pipe was exposed that carried water from the high-level aqueduct to the Roman praetorium in the southwestern part of the city. The southern Herodian wall was still standing when the imperial theater that replaced the Herodian theater was constructed (according to the Italian excavators, under the Severan dynasty).

In 2000, part of a semicircular structure (external diameter c. 85 m) was exposed approximately 200 m east–southeast of the theater. It has perimeter and radial walls separated by wedge-shaped “rooms” narrowing toward the center. In plan, the structure recalls the vault system supporting the cavea of a theater. About 50–60 m to its north, part of a building with three entrances (the central one in a curved niche and the other two in rectangular niches) was excavated in 1985 by M. Peleg and R. Reich. They described the structure as a “city gate in the southern wall of Byzantine Caesarea,” but it appears that the “gate” of the Peleg-Reich excavations was in fact part of a scaenae frons of a theatrical structure. This structure and the semicircular structure of the 2000 excavation should probably be interpreted as a theater or an odeon, perhaps the odeon mentioned by the Byzantine chronicler Malalas (Chron. 10, 46).

Outside the city wall, part of a villa of the second–third centuries CE built on top of the eastern kurkar ridge was excavated by the IAA. A well with a water wheel (saqiya), as indicated by the typical pots found on its bottom, supplied water to the villa.

A cemetery extended outside the city walls, mainly in areas unsuitable for cultivation. Most of the burials were in pits lined with stones or terracotta tiles, and in several cases in burial caves carved out of the kurkar crest east of the city. One of the loculi caves with a pit for the collection of bones apparently served the Jewish community. At the end of the first century CE, the area outside the southern wall west of the rectangular tower was converted into a cemetery that was delimited on the south by a stone wall. In the section excavated, 34 stone-built cist graves were found with tombstones in the “Italian” style, similar to those on the Via Appia. The bodies were cremated in 4 out of the 11 tombs examined; the others were articulated skeletons. In some of the tombs the coffins were made of terracotta tiles stamped L X FRE, an abbreviation of the name of the Tenth Roman Legion. In a number of cases, Latin or Greek inscriptions engraved on marble slabs were placed atop the tombs, however none were preserved in situ. Numerous burials of infants and fetuses were found in truncated jars or in cooking pots dug into the ground between the stone-built tombs. The finds in the tombs were very meager and consisted mainly of sherds and lamps from the second–third centuries CE. In tomb L40279, a coin of Hadrian was found near the left shoulder of the body. In tomb L40259, a young girl was interred with her gold earrings, and gold and silver rings. The cemetery served the pagan community of Caesarea and was perhaps intended for the officials of the praetorium. By the third century it was no longer in use and its area was confiscated for the urban expansion beyond the southern Roman city wall.

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. The change in status of the province of Palaestina as a result of the unification of the empire under Constantine the Great and the recognition of Christianity as the religion of the empire (324 CE) led to changes in civic buildings of the provincial capital Caesarea and an increase in construction in the city. The Roman praetorium of Palaestina Prima was moved and its functions divided among several building complexes in different parts of the city. The area of the Roman praetorium and the adjacent Herod’s circus was used for private dwellings and municipal buildings, with two courtyard buildings erected on top of the northern and southern wings of the abandoned promontory palace. Above the outer wall of the eastern cavea of the circus two rows of marble columns, perhaps a promenade, now extended southward above the office of the frumentariorum toward the theater. Public toilets, built partly above the eastern wall of the entrance of the abandoned palace, were incorporated into the southern gate of Herod’s circus.

During the fourth century the western part of the temple platform was extended westward as a vaulted structure into the square west of the original building. The foundation trench of the excavated vaults cut through earlier floors and a new higher floor was associated with them. A thick plaster floor was laid on top of the vaults. The assumed Herodian stairway was moved to the area west of the façade of the vaults.

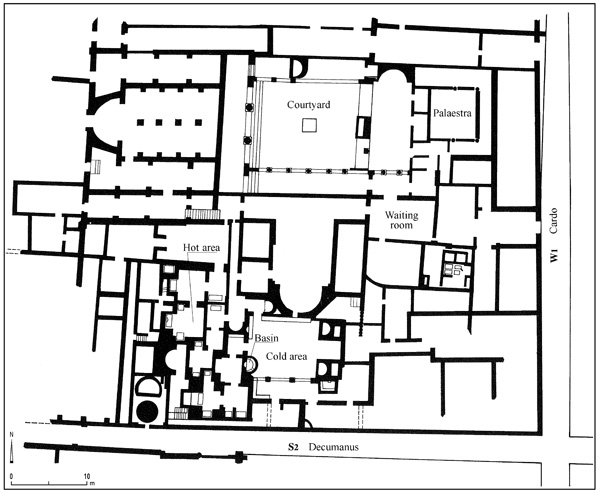

In the fifth century a public bathhouse was erected in the southern part of insula W2S3, above the building that replaced the Roman mansion in the third century. In addition to hot and cold bathing areas, the bathhouse included a dressing room (apodyterium), a magnificent palaestra, public toilets, rooms, and courtyards. The caldarium complex in the western part of the bathhouse was built on top of a fill that covered the eastern cavea of Herod’s circus. The bathhouse consisted of two adjoining bathing complexes which could be operated in unison or separately, either as summer and winter facilities or as separate units for men and women or different classes. The larger wing of the bathhouse was arranged along a circular route and, after its renovation, along two back and forth routes, similar to the original arrangement in the smaller complex. On the floor of the frigadarium of the small complex a marble sculpture of the torso of a woman from the Roman period was found, having been put to secondary use there as decoration. Water was supplied to the bathhouse through clay pipes leading from the municipal conduit passing under cardo W1. The bathhouse was later detached from the municipal water supply and received water from a well with a water wheel in the southwestern area. (On the CCE’s excavations of the warehouse complex adjacent to the bathhouse to the north in their area KK, see below.)

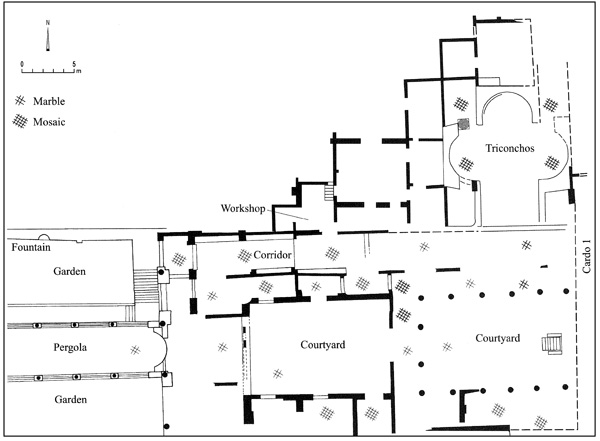

In the sixth century, after the promenade from the beginning of the fourth century went out of use, a palace was built in the southern part of insula W2S4. The palace included a courtyard surrounded by rooms, as well as a courtyard with columns on three sides; to its north was a trefoil-shaped hall (triconchos). The western side of the palace was occupied by an irrigated sunken garden with a stone-built pergola. The western wing (garden and pergola) was dug into the fill that sealed Herod’s circus and damaged the lower rows of seats. The palace was paved with marble and mosaic floors; some of the walls were covered with marble panels. In debris on the floor of the trefoil-shaped hall were fragments of a multicolored mosaic with human figures that had covered the walls. A mosaic-paved corridor connected the various wings of the palace. Two rooms of a complex north of the palace were attached to the palace complex by a doorway cut in the northern wall of the corridor. On the plaster floor of the larger room was found a layer (0.3 m high) of cut stones of various colors that had been inlaid in opus sectile panels prepared to decorate the walls. The room served as the workshop where the stone pieces were cut and the opus sectile panels were produced. In the workshop were also found raw materials, partially cut pieces of stone, production waste, and tools. The systematic manner in which the panels were stored and the sealing of the room from the outside indicate that the cessation of production was planned in advance, perhaps in the face of some kind of danger (such as the Persian invasion of 614 CE or the Arab siege and conquest of 640/641 CE) with the intention having been to subsequently return to work. The statue of a magistrate with head and arms cut off, found in a pile of stones in this area, may have come from the palace.

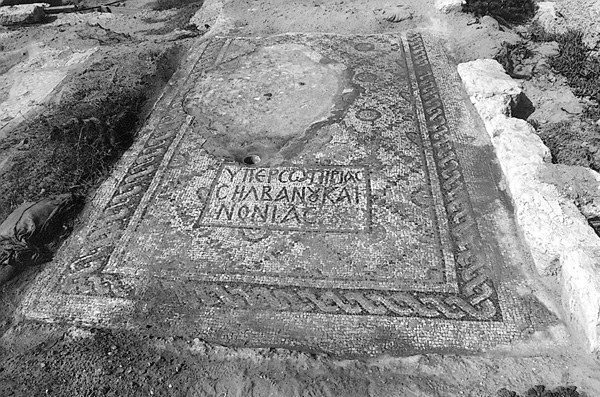

Above the ruins of the southern part of Herod’s circus, a building of basilical plan on an east–west axis was exposed. It consisted of a hall with an internal apse, a narthex, and an atrium, and was probably a church. The hall was paved with a multicolored mosaic with geometric motifs and a Greek inscription: “For the salvation of Silvanus and Nonias.”

In the area between the Byzantine palace and the basilica were uncovered portions of buildings paved with mosaics that were erected after the promenade went out of use. One of the mosaic floors was decorated with a partly damaged Greek inscription of seven lines that reads: “Ioanis son of Procopius paved the…in memory of …in the month of March…Amen.” The mosaic floor of another hall (c. 9.2 by 4.6 m) was decorated with round medallions (c. 0.45 m, external diameter) arranged in 15 parallel rows, seven medallions to a row, each medallion containing a depiction of a bird. To the west of the hall was a stone-built fishpond that apparently belonged to the building. Among the buildings of the Byzantine period destroyed when their stones were plundered in a later period were several rectangular stone storage facilities built inside pits (called cellar granaries or cellar bins). The granaries were always built in even-numbered groups of two, four, six, or eight.

Salvage excavations carried out in 1999 northwest of the theater exposed a public toilet complex from the Byzantine period that probably served those attending the theater. When the building went out of use, its drainage channels were filled with debris and a large amount of sherds from the end of the sixth–beginning of the seventh century CE.

The remnants of an east–west wall from the Byzantine period (c. 3.8 m wide) were found under the western section of the southern Crusader fortification. The wall terminated about 5 m west of the eastern quay of the Port of Sebastos, and its foundation was dug below sea level. It seems that the wall was part of the harbor’s southern breakwater, which was repaired during the reign of the emperor Anastasius I (491–518 CE). In 2000, a section of the southern wall of Byzantine Caesarea was uncovered (21 m long, 2.65 m wide) c. 10 m south of the Roman theater/odeon, i.e., about 50 m south of the line of the Byzantine wall proposed by M. Peleg and R. Reich.

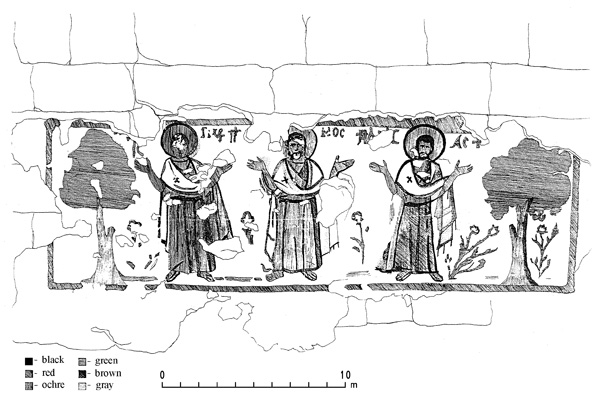

In 2004, the IAA reopened as part of a conservation project the area of the figurative mosaic excavated in 1955 by S. Yeivin on a hill about 500 m outside the Byzantine fortifications to the northeast. Yeivin had suggested that the figurative mosaic belonged to an unroofed church, associated with the nearby cemetery, but R. Reich and others assumed the remains belonged to a Byzantine villa. Limited excavations directed by Y. Porath were carried out in 2005 south and west of the figurative mosaic. It was shown to belong to an elegant central courtyard of a large mansion (over 50 by 45 m). Fragments of mosaic floors uncovered in the debris over the intact mosaics of the ground floor indicate that several rooms of the mansion had a second story. The mansion was destroyed by fire and the stone walls were later dismantled and removed. The artistic style of the mosaic floors and the finds revealed upon them date the mansion to the Byzantine period (sixth–mid-seventh century CE). The most splendid find is the surface of a wooden “sigma” table (1.04 by 0.97 m), made of an inlay of glass plates that fell face down on the mosaic pavement (the wood tabletop and legs were burnt to ash). The square plates of the inlay (c. 4 by 4 by 0.5 cm) were produced as flat pieces in gold glass technique, then pressed into molds to create a relief of a cross or flower. Since the mansion was decorated mainly with secular motifs, and only a few typical Christian motifs, it probably functioned as the residence of a respected and wealthy member of the bureaucratic-political or commercial elite of Caesarea. It seems that the mansion, located outside the walls of Caesarea, was destroyed in a raid prior to (or during) the Arab siege and conquest of Caesarea (640/641 CE).

From probes made in 1990 north of the Byzantine wall and east of the low-level aqueduct, it appears that the surface level in the Roman–Byzantine period was lower than at present. The areas up to c. 5 m above sea level were irrigated and used for cultivation, the soil enriched by the dumping of the city’s organic waste. Higher land was used for burial. In the lower areas were exposed a pool that received water from a well, a section of a masonry irrigation system, and part of a room with a multicolored mosaic floor.

In 1992, Y. Ne’eman discovered a section of a paved road running outside Caesarea to the east, probably the road to Megiddo. It crossed

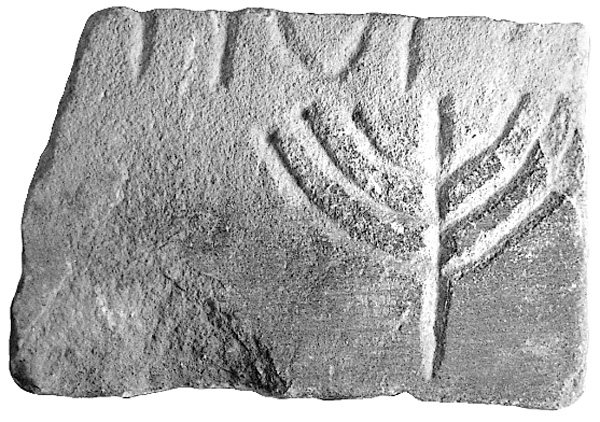

Outside the Byzantine wall, cemeteries extended around the city, mainly in areas unsuitable for agriculture. In 1992, a cave with arcosolia carved out of the kurkar ridge was excavated southeast of the city. In the cave sealed lamps of a type generally associated with the Samaritans were recovered. Three of the lamps were decorated with a seven-branched menorah. Soot was found on all the nozzles, even though the seal on some of the lamps had not been broken. In 2002, a section of a cemetery was exposed in the dunes east of the city with cist graves lined and covered with kurkar stones. In several of the graves the dead were interred in limestone sarcophagi.

THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD. With the Arab conquest of 640/641 CE and the resulting loss of Caesarea’s political-administrative status and cessation of maritime trade, the municipal network collapsed. Many of the inhabitants left the city, a large number of its buildings were abandoned, and the aqueducts leading into the city fell into disrepair (see below). An example of these changes was seen in the excavations in the southwestern sector of the city, where the imposing Byzantine buildings—the bathhouse, palaces, basilica, storerooms, and granaries—were no longer used in the capacities for which they had originally been built. The plundering of all the portable furniture and objects was followed by the systematic removal of wooden fixtures (roofs and doors), metal fittings (hinges, pipes, and clamps for fastening the marble panels), and valuable stone articles (columns and their components, marble panels lining the walls, and floor tiles), and eventually the dismantling of the walls. Dismantled marble objects were piled up in the palaestra of the bathhouse and the sunken garden of the Byzantine palace in insula W2S4, having been prepared for transport from Caesarea. In the complex south of the bathhouse were piles of kurkar stones that had been detached from the walls and sorted for reuse.

The remaining occupants of Caesarea were concentrated mainly near the harbor and in a few rooms of the abandoned Byzantine structures. Between the abandoned and half-dismantled buildings, garden plots were laid out for cultivation, enriched by soil and organic waste, ridded of collapsed stones, and fed by a new irrigation system using water from wells dug for this purpose. The lower parts of the walls were left in place to serve as protection from wind, sand, and salt spray from the nearby seashore. The advanced irrigation network was uncovered in the rooms of the ground floor west of the palaestra of the abandoned bathhouse. (See below similar findings from the CCE’s excavations in their areas CC, KK, and NN.)

In excavations conducted northwest of the theater in 1999 it became evident that the fortress (fortezza) which replaced the theater was constructed after the middle of the sixth century (contrary to the claims of the Italian excavators). The northern wall of the fortress incorporated walls of the Byzantine structures, including the public latrine noted above. The sherds recovered in the concealed channels of the latrine postdate the middle of the sixth century CE. If this fortress is not the kastron mentioned in Christian sources as existing in Caesarea during the Persian conquest (614–627/628), it must have been constructed after the Arab conquest (640/641), when the Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik ordered the city to be fortified.

Evidence that Caesarea once again became a fortified city during the rule of the Abbasid caliphs was uncovered in the IAA excavations. The southern wall (2.8 m wide) of the Abbasid city was discovered beneath the Crusader wall. The wall’s western extension was constructed above the wall attributed to the renovation of the harbor’s southern quay by the emperor Anastasius I; the continuation of the wall ran eastward along a straight course above the buildings of the Roman–Byzantine city. A cellar granary typical of the Abbasid period was uncovered along the inner face of the wall; it was later filled in during the construction of the Jaffa Gate of the Crusader wall.

The harbor of Caesarea was prepared for use once again and the western part of the inner basin was cleaned of sediment. The earth removed in the deepening of the harbor was deposited above the Byzantine remains south of the Early Islamic city wall, at a distance that would not endanger its defenders, while helping to prevent further destruction to the partially dismantled Byzantine buildings. Thus, three mounds of sand were created, mixed with shells, sea-pebbles, and a large quantity of Roman and Byzantine sherds. Many of the sherds bore signs of marine wear and encrustation, attesting to a lengthy period of submersion.

The vaults west of the temple platform, constructed at the beginning of the fourth century CE, were not properly maintained after the Arab conquest. The vaults north of the stairway connecting the harbor esplanade with the top of the temple platform collapsed and were filled with a sloping earthwork that contained eighth–ninth-century CE sherds. On the sloping surfaces, a road was paved running east–west and flanked by houses built on a gradual incline. Cisterns were dug into the fill beneath one of the houses. The vaults south of the stairway were completely preserved; two of them contained lime kilns. In the area of the upper square, south of the vaults, were bronze and iron smelting installations. These installations attest that at the beginning of the Islamic period building material was taken from the abandoned Byzantine structures and recycled in workshops on the site. In a later period, the area above the southern vaults was again leveled and paved with a layer of lime mortar on a

During the Abbasid-Fatimid period, water was supplied to the city by wells, cisterns, and springs near the seashore. In 1990, a stone-built channel was exposed which carried water from a spring near the shore, adjacent to the southern city wall. The Persian geographer Nasir i-Khusraw’s description of “springs issuing into the city,” apparently refers to this channel.

The inhabitants of Caesarea in the Early Islamic period prepared agricultural plots among the ruins of the Byzantine city by dismantling the early buildings, clearing the stones, and spreading organic waste from the city dump. When the arena of the eastern circus was prepared for dry farming, large stones not reused in construction and too heavy to stack into heaps (marble blocks from the spina, granite posts, and fragments of sculpture) were thrown into pits dug into the ground. In the dunes south of Byzantine Caesarea and up to the mouth of

The cemetery of the Early Islamic city extended outside the walls. The dead were interred in articulation, generally oriented east–west in pit graves dug between the ruins of the Byzantine city and in the sand deposit accumulated after the deepening of the harbor. Muslims were laid on their right side, their head to the west and face to the south toward Mecca.

In 2002, a hoard of 79 gold dinars from the Fatimid period was found (the latest coin minted in 1085/1086 CE). It had been concealed either during the turmoil of the eleventh century or on the eve of the Crusader conquest.

THE CRUSADER PERIOD. The southern wall of the Early Islamic period continued in use after the Crusader conquest (of 1101 CE). Towards the end of the Crusader period, during the reign of Louis IX, King of France, the southern wall was rebuilt and reinforced with a fosse and a glacis (in 1251/1252 CE). In the west, the city was separated from the fortress by digging a wide trench, turning the fortress into an island above the harbor. In the southern wall a gate with an inner tower (Jaffa Gate) was added above the cellar granaries of the Islamic period, which were filled with the city’s waste, including numerous sherds from the tenth to thirteenth centuries CE.

The southern vaults of the temple platform, where the Crusader church was erected, existed until the end of the Crusader period. The columns in the southern aisle of the church were built on solid foundations that contained fragments of columns and capitals plundered from Byzantine buildings dug deep into the fill of a Herodian compartment.

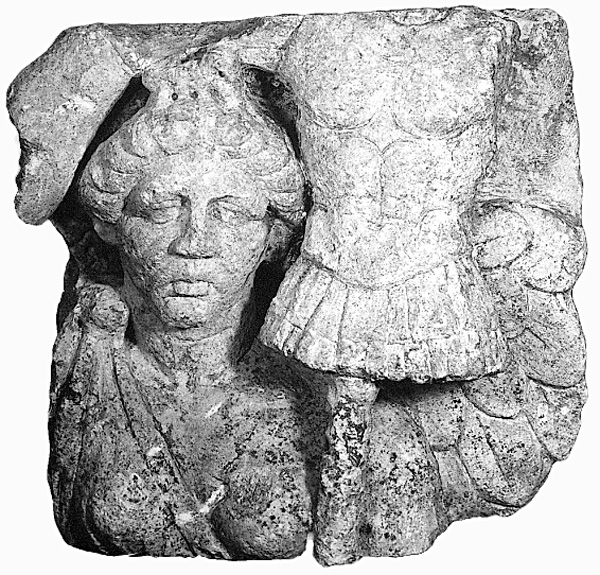

During conservation work in the northeastern corner of the Crusader wall, which was constructed during the crusade of Louis IX, a Crusader building of the twelfth century was discovered abutting the wall. Two columns of gray granite with marble capitals uncovered in situ in the Hebrew University excavations of L. Levine and E. Netzer belong to this building. (The excavators identified the columns as part of a tetrapylon or the junction of streets from the Roman–Byzantine period.) The columns supported a construction, perhaps an arch, from which typical twelfth-century statues of “demons” projected to the north. It thus appears that prior to the city’s fortification by Louis IX, the Crusader city of Caesarea extended northward over a larger area.

THE WATER SUPPLY. The present groundwater level at the site on which Straton’s Tower and Caesarea were established is c. 30 cm above sea level near the shore; before water was pumped from modern wells, the water level was higher toward the east. A survey and excavations in the area uncovered three springs from which water was conveyed in pipes and channels: at the round tower in the harbor, at the end of the southern wall of the medieval city, and at the abrasion shelf south of the Byzantine city wall. In all periods the inhabitants of Caesarea received a supply of water from wells dug down to the groundwater level and from the springs along the shore. Caesarea also obtained water from outside the city by means of three water-supply systems that were constructed during the Roman–Byzantine period.

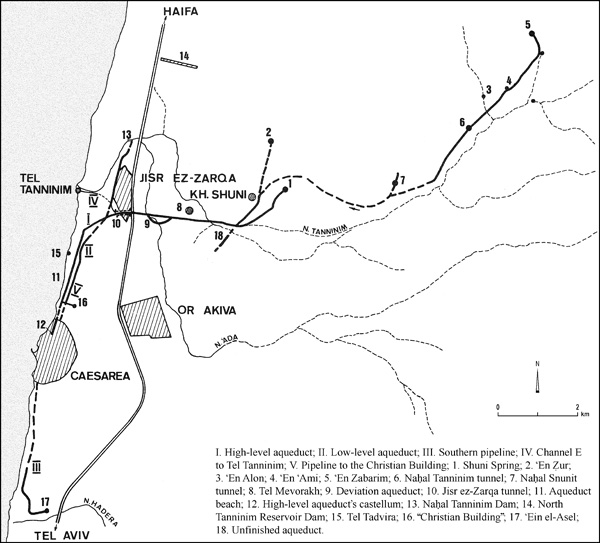

The High-Level Aqueduct. The aqueduct, starting from the Shuni Spring and other springs in the upper basin of

Channel B was replaced by channel C, which was built on top of the fill that blocked channel B and reached Caesarea c. 2.1 m higher. A section of the course of channel C, in the

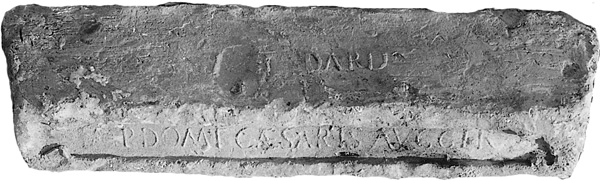

Channel B was built in the days of Hadrian (117–138 CE), as indicated by Latin inscriptions on the exposed side of the channel. The date of the construction of channels A and C does not appear in historical sources or inscriptions. It is generally agreed that channel A was built in Herod’s time, but its omission by Josephus in his description of the construction of Caesarea, together with the quality of its plaster and the results of the archaeological excavations in the 1990s, support the view that it was built later, during the first century CE. Channels C and D were probably built in the fourth century CE, as is evidenced by an inscription from 385 CE found near the point where channel D rejoined the course of channel A.

Channel A also supplied water through clay pipes to three imposing buildings (probably monasteries) from the Byzantine period located north of the city: one at Tel Tanninim, one at Tel Tadvira, and the “Christian Building.” The pipe leading to Tel Tanninim was later replaced by a masonry channel, which was partly supported by a wall of arches using the cement casing of the pipeline as its foundation. The “Christian Building” is located east of the low-level aqueduct and the clay pipe leading to it passed over the vault covering the aqueduct.

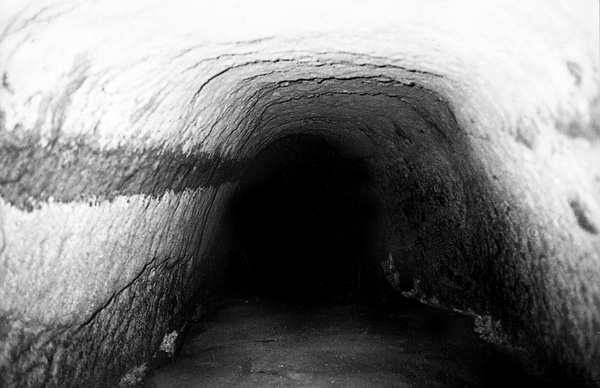

The Low-Level Aqueduct. The low-level aqueduct carried water from the

The Southern Conduit. A pipe was laid in the Byzantine period to carry water from ‘Ein el-Asal, in the lower course of

The Unfinished Aqueduct. This aqueduct, uncovered in Binyamina, was meant to carry water from the springs in the upper reaches of

The Lower Aqueduct. After the Arab conquest, when Caesarea lost its political and economic power and many of its inhabitants abandoned the city, the remaining population could not maintain the complicated system that brought water from outside the city and the system was neglected and ceased to function. During the Middle Ages, the needs of the inhabitants were met by installations near their homes: wells, springs near the shore, and cisterns that stored rainwater. The uncompleted lower aqueduct built in the tenth to eleventh centuries alongside the southern city wall to carry water from a spring near the shore (exposed in 1990, see above; see also

YOSEF PORATH

THE COMBINED CAESAREA EXPEDITIONS EXCAVATIONS

EXCAVATIONS

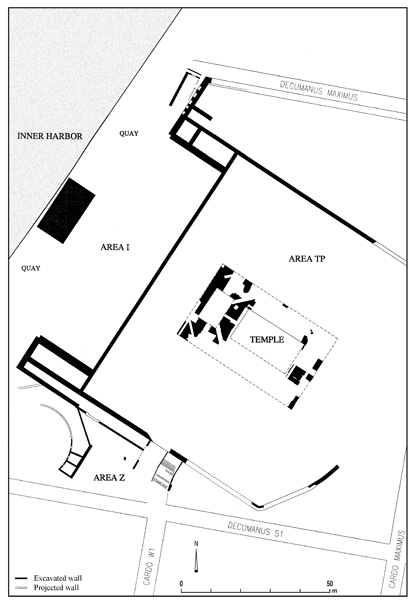

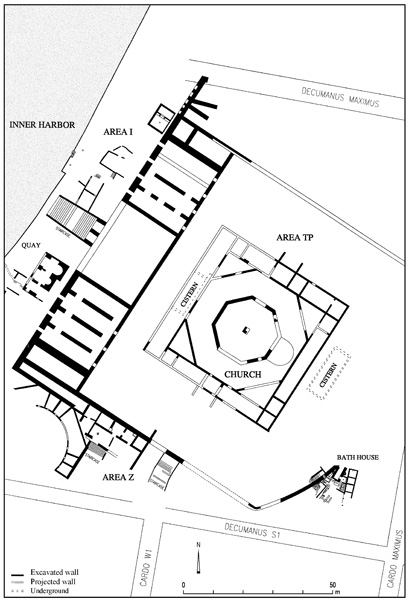

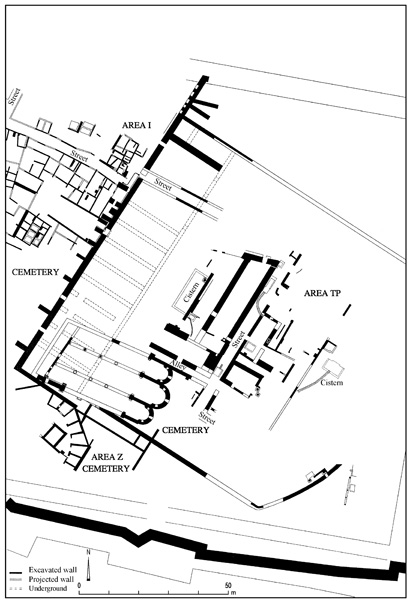

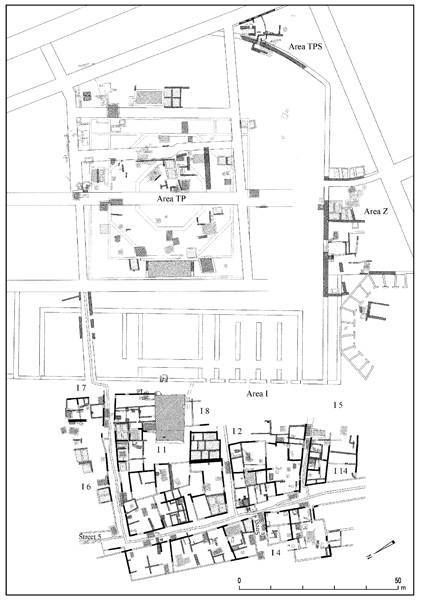

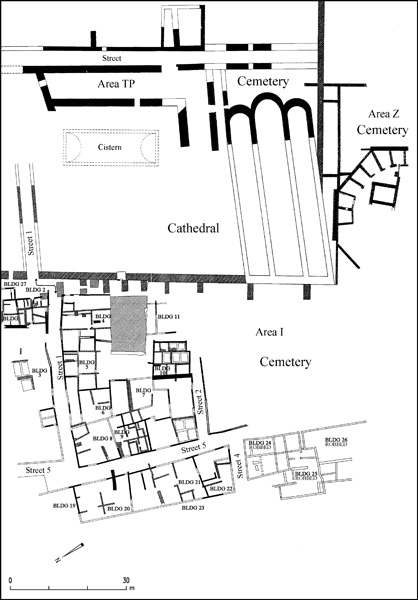

During the 1990s the face of ancient Caesarea underwent dramatic change as excavations on an unprecedented scale exposed much more of the site and resolved earlier puzzles and misconceptions. The Combined Caesarea Expeditions (CCE) organized in 1989 by A. Raban, of the Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa, and K. G. Holum, of the University of Maryland, continued work through much of the decade and, on a more limited scale, into the new millennium. In 1993, J. Patrich joined the CCE directorate on behalf of the University of Haifa. Inside the Old City, K. Holum directed excavations on the temple platform (area TP) and in a warehouse quarter north of the inner harbor (area LL). A. Raban led excavations at the presently land-locked inner harbor and its eastern quay (area I), and at two sites along the southern edge of the temple platform (areas Z and TPS). J. Patrich excavated south of the Crusader city in areas CC, NN, and KK. In area KK, he uncovered six warehouse units, while area CC, formerly field C of the Joint Expedition to Caesarea Maritima (JECM), contained a government complex that accommodated the Roman provincial procurator and later the governor of Byzantine Palestine. The CCE team also devoted effort to area CV, the western side of the area CC vaults, and its maritime unit conducted underwater excavations in the harbor.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

AREA LL. In area LL the CCE team renewed excavation of a quarter north of the inner harbor that L. Levine and E. Netzer had first explored in 1975–1976 and 1979. An east–west street through the quarter angled north of the orientation that Herod’s street grid required, so the alignment was thought to date from Straton’s Tower, but only a few soil layers and quarrying in the bedrock confirmed Hellenistic occupation. The street itself and its underlying drains underwent at least four phases of rebuilding between the first century CE and the later sixth, the ultimate phase consisting of a durable pavement of hard limestone slabs. At right angles to this street, extending southward toward a stone-built quay 23.7 m long on the inner harbor, stood a large warehouse (horreum). This structure measured 45 by 20 m and consisted of storage rooms arrayed on both sides of a central corridor, probably with a second story. Built originally in the late first century BCE as part of Herod’s port facilities, this warehouse was eventually dismantled sometime in the Roman period but was completely reconstructed in c. 400 CE on the same foundations. It then functioned until the 630s CE, the eve of the Muslim conquest, as part of the annona, the elaborate imperial apparatus that supplied grain, wine, and other commodities to the army and civil service. The CCE excavated three rooms of this warehouse, as well as part of the central corridor, down to the original lime plaster and tessellated floors.

The CCE team, like Levine and Netzer, discovered an abandonment layer lying upon the warehouse floors, a dense deposit of ceramic vessels for storage and transport, together with numerous coins dating no later than the 630s. Also from this layer came a set of gold ornaments that once decorated the belt of a senior military officer or civil official, a man named Stephanos to judge from the inscription on a belt buckle. Above this deposit, signs of building collapse appeared, including fallen structural blocks and burned wooden beams, and above the collapse was a layer of drifted sand, suggesting decades of utter desolation.

Like Levine and Netzer, the CCE dated the collapse and desolation in area LL to the period after the Muslim conquest of 640, and its reoccupation to the later seventh and eighth centuries. Area LL now became a domestic quarter of Muslim Caesarea, like others excavated recently inside the Old City in areas I and TP. Cross-walls blocked the former east–west limestone street, and the entire area was subdivided into about five dwelling units consisting of small rooms arranged around courtyards. The layout of the occupation had changed completely. Access was now apparently by narrow lanes from the north, west, and south. Floor levels were raised in two or three stages between c. 700 and 1000 CE, and beneath the courtyards and rooms, paved with kurkar slabs or mosaic pavements, the builders installed wells, cisterns, and the ubiquitous sinkpits for waste water. One former warehouse room now contained a large subterranean grain bin, lined with stone slabs. Although a century earlier in date, it was similar to grain bins from c. 1000 CE found next to prosperous Muslim dwellings throughout the Old City. The same domestic occupation apparently continued into the Crusader period. Of special interest was an apparent fortification tower that the CCE began excavating on the northwestern side of area LL, perhaps part of the coastal defenses of Muslim and Crusader Caesarea. What remains of the tower now measures 8 by 8 m, but only the northern, eastern, and southern walls still stand, and the entire western half may already have fallen into the sea. The walls are kurkar masonry c. 1 m thick, surviving as high as c. 8 m above sea level but with heavy buttresses at the corners that indicate considerable additional height. Flat but pointed arches pierce the northern and southern walls. The dating is still uncertain, but the architecture appears to be Islamic and may belong to the ninth or tenth century.

AREA TP. Area TP, the temple platform, rises to the east of the inner harbor. Josephus’ War I, 414 refers to it as a “hill of earth,” but actually it is a ridge of bedrock that Herod’s builders elevated and extended with retaining walls containing an earth fill, thus forming an esplanade large enough to accommodate a large temple and its surrounding porticoes. No trace of the porticoes exists, but they may be restored by analogy with Josephus’ description of the porticoes of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The temple platform’s full extent, far smaller than its Jerusalem counterpart, was about 90 m east–west and 100 m north–south, and the esplanade on top, presumably paved with stone slabs, lay at about 11.5 m above sea level. Upon it Caesarea’s most sacred religious buildings rose throughout the centuries, above the city’s essentially flat terrain.

The inhabitants of Hellenistic Straton’s Tower, upon the ruins of which Herod built Caesarea, may already have worshiped on this very spot in a temple dedicated to Aphrodite as Isis-Hella-Agathe, but so far no archaeological evidence has come to light. The CCE did discover massive remains of Herod’s magnificent temple to Roma and Augustus, built when he founded the city in 20–10/9 BCE, and of an octagonal early Christian church constructed largely of its reused stones about 500 CE. After the church collapsed in the earthquake of 749 CE, the Muslims built the town’s Great Mosque somewhere nearby. Though mentioned by Muslim geographers, it has thus far not been identified in the remains. In the twelfth century, the Crusader conquerors built here the triple-apsed basilica of St. Peter that A. Negev cleared in the 1960s.

Subsequent stone robbing, as well as subterranean cisterns, sinkpits, wells, and deep foundations of later occupations (see below), destroyed most of the temple, the church, and other occupations, but enough fragments survived to recover the plans and elements of the superstructures. From the Hellenistic period (Straton’s Tower, third–second centuries BCE) only a few dissociated building stones came to light in the area TP excavations, along with a 1.9 m segment of a crude north–south retaining wall.

Ceramic evidence and coins confirm construction of the Roma and Augustus temple late in the first century BCE, and indeed, Josephus connects it with Herod’s original building campaign of 22–10/9 BCE. In his descriptions, the historian emphasizes the building’s exceptional scale and the colossal size of the statues of Roma and Augustus that it housed (War I, 414, cf. Antiq. XV, 339). The remains consist, first, of numerous fragments of the temple podium’s deep foundations. These were large blocks of the local kurkar sandstone joined together and to the underlying bedrock with a heavy dark gray mortar. Interior stones were irregular, but facing stones had been cut square, in some cases with bosses on the exterior subterranean faces. The foundations represent a podium 28.5 m wide north–south and 46.2 m long. The relatively narrow 2.8-m-wide foundation on the west would have accommodated a colonnade of six columns while the 7.8-m-wide foundations on the north, east, and south supported both a free-standing colonnade and the cella walls; so the temple was presumably peripteral and prostyle, i.e., it had a surrounding colonnade and a colonnaded porch on the west looking out over the harbor. Nothing more can be said of its plan, but many superstructure fragments have also survived, including bases, segments of column shafts, capitals, and entablature. These permit reconstruction of the Corinthian order, nearly 22 m high from the podium to the top of the architraves. Columns, architraves, and presumably other architectural elements had received a thick coat of hard, white stucco, with molded fluting in the case of the column shafts. This stucco protected the friable stone from rapid weathering and left the impression of marble construction. The height of the podium is unknown, but its upper surface must have been about 4.2 m higher than the level of the paved esplanade. With its pediments, therefore, Herod’s temple was indeed a building of majestic proportions, towering over 30 m above its surroundings.

Excavations in area Z on the south and southwest flanks of the temple platform exposed about 20 m of the southern retaining wall in this sector, 1.52 m wide, also dating from the Early Roman period (see below). Remains of a staircase also came to light, at least 6 m wide, that provided access to the temple platform from the south, in line with one of the north–south city streets. On the west, A. Negev had already exposed parts of the temple platform’s western retaining wall 17 m west of the temple podium. On this side, projecting arms to the north and south embraced the inner harbor and linked the temple platform with the harbor in one grand architectural conception. Midway between these projecting arms, exactly on the temple’s centerline and just inside the inner harbor quay, the excavators discovered a massive foundation of masonry and poured concrete, 9.4 m east–west and 20 m north–south, likewise Early Roman in date, interpreted as the foundation of the cult altar. Upon this altar the priests would have sacrificed bulls and other animals to Roma and Augustus during periodic festivals. In the space between this foundation and the western retaining wall a broad staircase presumably provided access from the inner harbor quay to the levels of the temple platform esplanade and of the temple podium itself. So far, however, the excavations have yielded no trace of this staircase.

The temple to Roma and Augustus appears to have survived more than four centuries, though cultic activity presumably ceased during the fourth century CE, when Caesarea and the Empire as a whole adopted Christianity. The striking archaeological evidence both for the building’s longevity and for its destruction c. 400 CE consisted of large detached segments of the molded stucco coating of a column uncovered in north–south alignment with fragments of the associated capital and the entablature. Apparently a standing column had collapsed northward and came to rest upon a soil fill at 11–11.5 m above sea level, where the paving stones of the esplanade had already been robbed. From the position of these fragments, buried in an early fifth-century layer as they had fallen, it is clear that the column still stood c. 400 CE, presumably with those adjacent to it, but the archaeologists could not determine whether the colonnade collapsed due to natural causes or was intentionally pulled down. Purposeful temple destruction at other cities during this period perhaps points in favor of the latter possibility. In any case, Herod’s temple was then systematically dismantled down to the lowest foundation courses, at 9.0–11.45 m above sea level, and its stones were taken for use in new construction.

The Intermediate Phase. The first phase of new construction dated no later than c. 450 CE. The builders buried the dismantled temple foundations in a fill that contained ceramics of the fourth and fifth centuries, creating a new occupation level at 11.5–12 m above sea level. Into this surface they dug the foundations for a new building or a building complex, oriented differently from the underlying temple and unrelated to it. The foundations, 60–70 cm wide, consisted of cobbles and fieldstones laid in

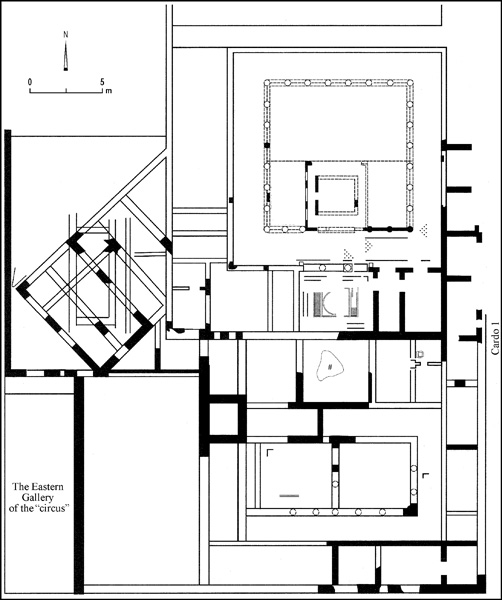

The Church Phase I. This desacralization lasted until c. 490, when Christian authorities constructed a new sacred building, a martyr church or martyrium, on the temple platform. Unfortunately, the team found no inscription identifying the martyr to whom the church was dedicated, but they did recover enough archaeological evidence to reconstruct much of the construction process and the building’s original design and history. It appears, first, that the church builders dismantled the intermediate building complex down to its foundations, recovered the stones for reuse in their own building, and then covered the entire building site with a fill that elevated the occupation level to c. 12.7 m above sea level. Curiously, they returned to the orientation of Herod’s temple, perhaps because, for purely technical reasons, they adopted, on the west, the deep foundations of the temple pronaos, to support the foundations of their own building. In plan the church foundations consisted of concentric octagons inscribed within concentric squares. The outer octagonal foundation, 39 m in diameter, was 65 cm wide and supported the outer walls of the church, while the heavier inner foundation, 1.1 m wide, supported an internal colonnade with corner piers separating the ambulatory and the central nave, together with an octagonal clerestory above it and a segmented hip roof or dome. These octagonal foundations comprised large kurkar blocks mortared together, many of which originated in Herod’s temple, and the circumscribed square foundations were of similar construction, the outer one measuring 50 m on each side. The square foundations represent square and rectangular side rooms intended for use as chapels or for storing liturgical vestments and vessels. They and the triangular corner spaces were all roofed, to judge from the absence of sub-floor drains for these rooms. Capacious vaulted cisterns on the west beneath the narthex and on the east did receive runoff from the building, but it came from the roofs of the octagon and the side rooms, through well-constructed downspouts attached to the interiors of the side room walls.

Unlike the temple, the church survived at floor level and even higher. Large patches of a pavement of large gray marble slabs came to light in the octagon; and in one of the side rooms on the east, already uncovered by A. Negev, the floor was opus sectile of red and cream stone slabs. Several superstructure blocks also remained in situ and lying about the site, some with clamp holes on their interiors and exteriors for attaching marble wall revetments. In the northern and southern walls of the outer octagon, jamb blocks and thresholds cut from reused marble column shafts revealed the positions of two doorways, and a single jamb indicated a third door opening into one of the side rooms from the northern entrance corridor. Inside the ambulatory, one of the eight corner piers and two square bases of the ambulatory colonnade remained in situ, demonstrating that the colonnade consisted originally of eight pairs of columns between corner piers, surmounted, of course, by Corinthian capitals, about eight of which survive, and probably by an arcade below the clerestory. In its original configuration the church apparently had no apse or raised bema for celebrating the eucharist, but a rectangular foundation below floor level in the exact center of the octagon revealed the position of the martyr shrine, perhaps in the form of a sarcophagus.

The Church Phase II. This configuration remained in service for only a short time, perhaps less than a decade, before the martyrium underwent conversion into a congregational church. Excavating on the eastern side of the building, beyond the eastern bay of the ambulatory colonnade, the archaeologists discovered substantial fragments of a second pavement level above the original pavement, the later one, too, composed of marble slabs. This pavement was positioned precisely between the two eastern corner piers, where two columns were evidently removed to accommodate it. The pavement fragments represented a newly installed bema, a raised platform for celebrating the eucharist that was semicircular on its eastern side and presumably surmounted by a semi-dome. Along the western side of this bema two steps were preserved, riveted with marble slabs, that led upward from the nave, and there were cuttings in column bases for the chancel screen that separated the bema from congregational space. No trace of the altar table has been identified, or of the synthronon for the clergy behind it, though these may confidently be assumed. Also uncovered was a marble disk 1.62 m in diameter with imprints of bases on its upper surface for small columns. This was likely the base of the church’s ambo, or preacher’s pulpit, which would have been positioned within the nave a short distance west of the bema. Hence in its second configuration, though apparently not in the first, the octagonal church accommodated the normal eucharistic liturgy, and in it the bishop or other clergy preached on occasion to the congregation.

Construction of the octagonal church entailed modification of the temple platform itself. In area Z on the southern flank, the Herodian period staircase was renewed in this period and remained in service (see below). On the west, the space between the projecting arms of the original design had been filled in, perhaps already in the third century, with a series of vaulted substructures that supported a 20-m extension of the temple esplanade toward the west. About 500 CE, perhaps together with construction of the church, a new staircase, 9 m wide, was built to provide access between the inner harbor and this extended esplanade. Like the church, its fabric contained numerous fragments robbed from King Herod’s temple.

After the Muslim conquest of 640 CE, the octagonal church survived for a century or so, perhaps functioning during part of this time as a mosque. Indications of earthquake destruction suggest the building’s ultimate collapse in the major tremor of 749 CE, and indeed, numismatic and ceramic evidence prove the establishment of a new kind of occupation on the temple platform in the later eighth century. This was a domestic occupation of substantial townhouses built around courtyards, similar to those in area I to the west (see below), but in area TP little more than subterranean structures survived, mainly the cisterns, wells, sinkpits, and grain bins that destroyed much of the evidence for the underlying church and temple. Somewhere nearby was Caesarea’s Friday Mosque, known from literary sources, but no trace of it has come to light. The townhouses, but not the mosque, continued after the Crusader conquest of 1101 CE, when the local bishop built the surviving Church of St. Peter on the temple platform’s southwestern flank. Finally, in the thirteenth century, only a generation or two before Caesarea capitulated for the last time to the Egyptian Mamelukes, the Crusaders of Caesarea established a new monumental occupation with deep foundations that destroyed still more evidence of the underlying occupations. This was a series of broad and deep foundations, generally not mortared but laid with earth in the interstices, which probably supported great vaulted Crusader halls, as large as 30 by 10.5 m, which might have accommodated horsemen and their mounts. These flanked a 3.8-m-wide paved street that ran across the temple platform north to south and intersected a narrow alley, likewise paved, against the north side of the basilica. When excavations began, the remnants of the medieval domestic and monumental occupation left little sense of the grandiose ancient buildings—pagan temple and Christian church—that lay below.

KENNETH HOLUM

AREA TPS. Area TPS is located at the southeastern corner of the temple platform, just outside and adjacent to its curved retaining wall, which was founded on quarried bedrock and survived to its full height of over 4 m. The wall, 1.2 m thick, was built during the time of Herod and subsequently rebuilt some five centuries later. In the rebuilding phase, a door was installed in its lower part, with four stairs leading up to a rather narrow passageway (0.8 m wide). Inside the passageway, a 1.5-m-wide flight of stone-slab stairs ascended westward, adjacent to the inner side of the wall, up to the surface of the platform.

Access to this passage was through a small Byzantine bathhouse, preserved almost intact to its second story. Built around 500 CE, it is triangular in plan, its apex facing north. The eastern side was delimited by a thin partition wall that cancelled the colonnade along the western side of Caesarea’s cardo maximus, transforming it into a series of large water tanks. The main room of the bath, the caldarium, is only 4 by 2 m, with two external apses in each of its long walls containing skylights. The tepidarium to the east is half the size of the caldarium. The floors and walls of both rooms had once been paved with thin marble slabs. The frigidarium occupied the broader eastern side of a large dressing room that was furnished with marble benches and a niche with marble shelves. The complex was entered through a door in a thin partition wall from a paved courtyard to the west. The bathhouse went through several phases of modification, but continued to function well after the Islamic occupation of 640 CE, probably as a purification facility for Christian worshipers on their way to the octagonal church.

Toward the beginning of the eighth century, at least part of the bathhouse was converted into a fish-processing factory, as attested by some shallow basins and quantities of jars containing fish. The entire complex was covered by building materials fallen from the upper floors, most probably during the earthquake of January 18, 749 CE. Soon after that, the area was leveled to an elevation similar to that of the temple platform. Domestic structures were installed there during the Abbasid and the Fatimid eras. In the tenth century CE, a well was dug just inside the blocked entrance that once connected the bathhouse to the high platform. During construction of the walls of the rectangular well, the doorway was exposed and refurbished as a cache accessible through the well shaft. Sometime later, probably in the first half of the eleventh century, this cache was packed with a hoard of metal vessels, huge glass containers, and assorted jars and tableware—most likely the personal belongings of a metal shop owner. The unclaimed hoard was exposed during the 1995 excavations and it seems to resemble the one found at Tiberias several years later. During the Crusader period the area was paved with stone slabs and may have functioned as an open courtyard.

In addition to the discovery of the curved retaining wall of the raised temple platform, which was the main sacred place at Caesarea throughout its history, the small Byzantine bathhouse and the Fatimid hoard, another important archaeological discovery in area TPS is the evidence for the yet undocumented scope of destruction caused by the earthquake of 749, clearly attested by the positions of the fallen columns in the western courtyard.

AREA Z. Area Z lies south of the western half of the temple platform and the great Crusader church. The southern retaining wall of area TP, which marks the northern edge of the excavation area, and a massive retaining wall running perpendicular c. 18 m south of it are the only structural features in the area dating to Herod’s reign. The space between these walls contained an earth fill, while east of the eastern wall in area Z-2, a broad stone-slab staircase probably dating to the Herodian period was exposed that ascended to the temple platform from the south along a slightly curved line, as if to amend the overall layout of the sacred area and to conform to the line of the harbor of Sebastos and Caesarea’s streets.

The main architectural feature of area Z is a sigma complex, a series of trapezoid chambers opening onto what appears to have been a circular plaza and backed by a massive polygonal wall. A unique aspect of this complex is its longevity—the same chambers remained in use from the Early Roman period until the Crusader conquest of 1101 CE, nearly one millennium. Eight of the chambers, comprising just short of one quarter of a circle, were excavated in the 1987 and 1994 seasons. Each exhibited a distinct stratigraphic sequence and all were either workshops or storage chambers during the Roman and Byzantine periods. In later phases, during the Early Islamic era, some chambers included indoor wells and/or two-story shops. Unique among the rich assemblage of small finds, including metal and glass slags, is a group of over a dozen small marble slabs covered in Kufic incantation texts of the Umayyad period inscribed in black ink.

During the Abbasid era, following the replanning of the city after the great earthquake, the Byzantine tessellated square in front of the sigma complex was built-up with dwellings, wells, and septic pits. Later, during the Fatimid period, these buildings were partly leveled, and the northern half of the circular square was repaved in stone slabs.

Beyond the sigma complex, to the east, an additional subsidiary staircase, just over 3 m wide, was installed toward the end of the fifth century CE, leading toward the temple platform, probably in conjunction with the inauguration of the octagonal church there. A series of shops whose rear wall was the massive retaining wall of area TP occupied the elevated space on both sides of the staircase, above the sigma, replacing a Roman (second-century CE) bathhouse to the east. During the Crusader period this area was used as a burial ground, under the paved courtyard of the church.

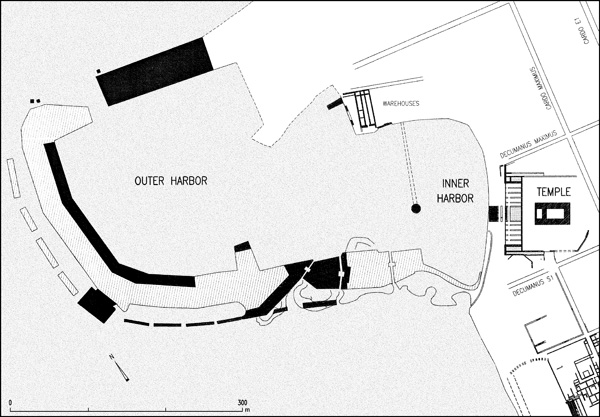

AREA I. The flooded basin of the inner harbor of Sebastos and its perimeter have been studied and partly excavated as area I, by and large as a preliminary step toward renovation as a tourist attraction. This basin, detected by CAHEP in the late 70s, turned out to be twice as large as formerly surmised—over 200 m from north to south and c. 100 m from east to west, with water at one time covering an area of just over 18,000 sq m to an average depth of c. 2.5 m. At present, c. 90 percent of that area is landlocked and most of it was found to have been built-up by late antiquity. Approximately half of it was excavated down to the wave-carried sand fill. The excavations extended eastward over the harbor’s original quay for c. 20 m, up to the series of vaults that comprised the western façade of the temple platform. (On the results of the underwater excavations of the harbor, see below.) The stratigraphic study revealed 16 occupational phases and an additional 10 sub-phases, which were marked by CCE as follows:

16: Hellenistic period—mostly second century BCE, Straton’s Tower.

15: Herodian period—c. 16 BCE–6 CE.

14c: Early Roman A period—rule of the procurators, 6 CE–70 CE.

14b: Early Roman B period—to the Hadrianic period, c. 70–118 CE.

14a: Middle Roman A period—to the Severan period, c. 118–190 CE.

13b: Middle Roman B period—to the reign of Gallienus, c. 190–268 CE.

13a: Late Roman period—to the Constantines, c. 280–330 CE.

12b: Early Byzantine A period—to the time of Honorius, c. 330–400 CE.

12a: Early Byzantine B period—to the time of Anastasius I, c. 400–500 CE.

11: Middle Byzantine period—until after Justinian I, c. 500–565 CE.

10: Late Byzantine A period—to the reign of Phocas, c. 565–600 CE.

9: Late Byzantine B period—to the Islamic conquest, c. 600–640 CE.

8b: Transition period—early Caliphate, c. 640–700 CE.

8a: Umayyad period—first half of the eighth century CE.

7: Abbasid period—mid-eighth to mid-ninth centuries CE.

6: Tulunid, Ikhshidid, and Abbasid periods—mid-ninth to mid-tenth centuries CE.

5: Early Fatimid period—mostly the last three decades of the tenth century CE.

4: Middle Fatimid period—first half of the eleventh century CE.

3b: Late Fatimid period—second half of the eleventh century CE.

3a: First Crusader Kingdom and Ayyubid periods—twelfth century CE.

2: Second Crusader Kingdom and Mameluke periods—thirteenth century CE.

1: Bosnian village—late ninteenth–early twentieth centuries CE.

The Hellenistic Period (Stratum 16). The structural remains include a single, continuous course of slender ashlar headers, running parallel to the eastern quay of the inner basin, some 12 m to the east, probably a lower step leading up toward a raised quay that had been dismantled during Herod’s reign. Quantities of second-century BCE potsherds, including some coins and a dozen stamped handles of Rhodian and Koan wine amphoras, confirm that date. It seems that this harbor basin, which was protected from the open sea by a wall that terminates on its southern end in a round tower 12 m in diameter, similar to those exposed by the Italian expedition to the north, was somewhat larger than the Herodian one. Masonry with dressed margins like that of the western façade of the temple platform has been found at the back of the vaults and on their flanks, up to a height of c. 7 m above mean sea level. This leaves them some 5 m too low to have served as the western retainers of Herod’s temple platform. They may be related to an earlier Hellenistic building phase, as indicated by their similarity to the inner face of the original phase of the city wall along the north coast. The northern city wall was probably the one referred to in the Talmud as marking the boundary of the Land of Israel, the “city wall of Migdal Sar” (probably a literal translation of the Greek name Stratonis Pyrgos). This wall may have been the administrative demarcation between the royal harbor of Sebastos and the municipality of Caesarea until 70 CE.

The Herodian Period (Stratum 15). Two major structural complexes completed before Caesarea’s inauguration in 10 BCE should be attributed to the city’s initial phase. One comprised the eastern and northern segments of the quay that encircled the inner harbor basin. This quay replaced the earlier Hellenistic one almost all around the basin, except for the very northwestern end of it, which was exposed (in areas S and SE) down to its base courses at 2.4 m below mean sea level. It was found to be built of large headers of elongated kurkar blocks, in a typical Phoenician style. Elsewhere, the quay was exposed for a stretch of over 120 m along the eastern side of the basin and at the southern and northeastern turns of its course. The Herodian quay comprised a base wall made of form-casted pozzolana concrete that had been installed on a quarried ledge of the kurkar bedrock, at 1.2–2.3 m below mean sea level, up to the sea level of the time, with additional courses of ashlar headers as high as 1.6 m above mean sea level.

The second monumental structure is a 20-m-wide staircase that ascended from the quay eastward to the temple to Roma and Augustus. This structure was built of large, well-cut kurkar blocks as a raised platform that was reached through a vaulted passage at the back and 3-m-wide stairs ascending westward through an arched vomitorium. Once on the elevated pier, the pilgrims would turn eastward and climb up the broad “imperial” staircase. This concept of indirect passage on the way to a sacred shrine resembles the one at the Herodian Temple in Jerusalem (at the so-called Robinson’s Arch) and might have enabled better control over the visitors (and perhaps even the charging of entrance fees, either to the Temple, the royal harbor, or both). Only the central half of the staircase remained, after it had been trimmed to half its original width during the Byzantine era. The landing pier survived intact, comprised of a massive 10-by-20-m rectangle of pozzolana concrete with ashlar blocks around its perimeter.

An additional installation that belongs to the initial phase is the flushing channel constructed with pozzolana concrete that runs along the southern half of the eastern quay of the inner harbor basin. The channel began at the water’s edge of the south bay as a funnel-shaped structure, broad and shallow toward the incoming wash of the breakers that would flow into it and ascend to just over 1 m above mean sea level to a settling basin. From the settling basin, the sea water flowed in a channel running northward behind the quay and parallel to it, emptying into the inner harbor basin some 40 m from the northeastern corner of the harbor. This flushing channel went out of use sometime around 200 CE, when it was filled by silt that had been dredged from the bottom of the basin. It seems that at that point in time the flushing mechanism had lost its efficiency due to the advanced segmentation and subsidence of the harbor’s western moles.

The Early Roman Period (Stratum 14). This period may be divided into three sub-phases. During the first one (14c), the inner harbor appears to have operated much as it had since its inauguration, with some additional features. One such feature was a prominent sewer tunnel, installed at the back of the quay at the base of the western façade of the temple platform and running parallel to it, from north to south. It was large enough for internal maintenance work (1.2 by 0.6 m across) and covered by large, well-cut ashlar slabs. During this first sub-phase the western temple façade already comprised two sets of four parallel vaults at each side of the royal staircase, each 21 m long by 5.8 m wide with a maximum inner height of over 8 m. A nympheum was installed at the northern end of this façade, facing the inner basin and draining into the tunnel. The harbor was still separate from the city as a royal, or official unit, as may be deduced from Caesarea’s epithet on its coins issued by Agrippa I and by Nero: “…By the harbor of Sebastos.”

The second sub-phase followed the First Jewish Revolt and the promotion of Caesarea to the status of colonia prima. Though the city continued to flourish as the metropolis of the Roman province, the harbor had begun to fall into a state of disrepair. There is archaeological and sedimentological evidence to indicate that its main moles had lost coherence toward the end of the first century CE: merchantmen foundered over the collapsed segments of these features and the surge into the harbor basin piled sand deposits within the inner basin (see below, Underwater Excavations). Some alterations were made during that sub-phase within the vaulted chambers of the western façade of the temple platform. Their original function may have been altered from storage facilities for naval units to storage facilities for commercial goods.

The main feature added during the third sub-phase was a platform or quay, comprised of loosely laid large ashlars that protruded from the eastern quay c. 8 m into the inner basin. This platform is 26 m wide, aligned with the royal staircase (c. 3 m wider than the staircase on each side). It was laid over deposits that cover the rocky floor of the basin to a depth of 2.2 m below mean sea level. It was held in place by a compacted pozzolana concrete matrix that was laid by hand (the fingerprints of the masons are still visible). A narrow staircase was added to the western front of the platform, descending southward to the rocky bottom of the harbor basin. Another, circular, flight of stairs was constructed at the northeastern corner of that platform, also leading down to the bottom of the basin. In view of the fact that the water level at that time was somewhat higher than present-day mean sea level, one may wonder how that complex was constructed and for what purpose. This additional mole may have served as an extended landing for the royal staircase, provided that the staircase was modified to ascend directly from the waterfront to the level of the temple. For the time being, the magnificent complex remains enigmatic.

The Middle and Late Roman Periods (Stratum 13). Not much has survived of the structural elements datable to this period within the area of the inner harbor basin and the western façade of the temple platform. Modifications were made within at least some of the vaulted chambers, including renovation of the vaulted roofs and portions of the side walls. Some of the passages connecting these chambers were blocked and their openings to the west were closed by thin partition walls, furnished with small rectangular doorways. During this period, some vaults appear to have been subdivided and wooden galleries were added, turning the storage compartments into two-story complexes.