Deir Qal‘a

THE SITE

Deir Qal‘a (or Deir Kulah) is located at the edge of a precipice, 370 m above sea level, on the northern banks of the Shiloh River, southwest of the Peduel settlement and some 1.5 km east of the village Deir Balut in western Samaria. Its elevated position afforded it control over the surrounding area and several junctions of secondary roads that crossed the riverbed and connected southern Samaria and northern Benjamin with the Coastal Plain.

EXPLORATION AND EXCAVATIONS

Deir Qal‘a is mentioned frequently in historical sources, often described as a Byzantine monastery due to the remains of a chapel found at the site, along with building stones bearing incised crosses. The nineteenth-century scholar V. Guérin describes an impressively fortified monastery and dates its founding to the fourth–fifth centuries CE. Early twentieth-century British surveyors, the first to map and draft a plan of the site, characterize the finds as a fortified castle and monastery of the Byzantine period. The 1968 survey of Ephraim and Manasseh suggests that this was a large manor house of the same period, a proposal supported by contemporary scholars and surveyors. Three seasons of excavations were carried out during 2004–2005 by Y. Magen and N. Aizik of the Staff Officer for Archaeology in Judea and Samaria, with the purpose of clarifying the connection between the fortified building and the chapel and other Christian remains at the site.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

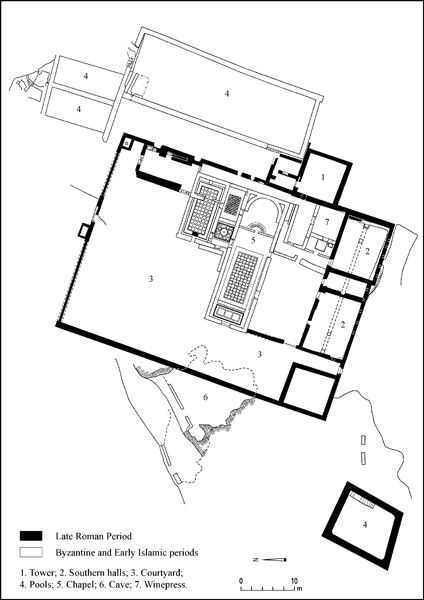

The site, encompassing an area of some 55 by 38 m, consists of a massive watchtower and an enclosure containing large rooms surrounded by a wall built of ashlars, some with drafted margins and projecting bosses. The stones were obtained from large stone quarries to the east of the site. The enclosure features a courtyard with a white mosaic floor, incorporating a chapel and additional rooms built in a later phase. Discovered to the east and north, beyond the line of the enclosure wall, were several large pools, the water from which was conveyed via sluices and stone-carved channels to pools and agricultural areas. An additional pool was found at the southwestern corner of the enclosure. These were probably first hewn as stone quarries, given their proximity to the enclosure itself.

A large natural cave with a gushing karstic spring was found at the base of the cliff upon which Deir Qal‘a was built; the cave was adapted for use as a dwelling, with remains of walls dividing the space into what may have been cells for monks. A stronghold built of hewn fieldstones was found some 150 m to the northeast of the site. It was accessed by a hewn staircase. The placement of the stronghold provided visual contact with the main watchtower. A lime kiln was added to it in a later phase.

Excavations revealed two main phases of occupation at the site. Phase A, the Late Roman period (fourth–fifth centuries CE), features the watchtower, stronghold, and quarries; whereas phase B, the Byzantine to Early Islamic period (sixth–eighth centuries CE), includes the construction of the chapel, changes in the arrangement of rooms and the courtyard, and the conversion of the stone quarries into pools.

The square watchtower (9.5 by 9 m, the walls up to 1.2 m thick), seemingly the first element constructed of the entire complex, protrudes eastward from the line of the enclosure wall. Its exterior face was built of large ashlars, the majority with drafted margins and protruding bosses; and its interior of small fieldstones, binding material, and plaster. The walls are preserved to a height of 7 m (8–10 courses). It has a narrow entrance (0.9 m wide) on the northern side. Early twentieth-century photographs show the complete entrance, its engraved lintel bearing a tabula ansata with a cross in the center. Seen above the lintel are indications of an upper floor, which was not preserved. The large stone threshold of the entrance was found during excavations. Carved across it is a drainage channel, which routed water to the inner reservoir, hewn and built under the tower’s foundation.

North of the watchtower and adjacent to it was once a large stone quarry (33 by 10.5 m and 6 m deep) which provided the stones for the tower. During the Byzantine period, the sides of the quarry were plastered and an ashlar-built wall added, raising the height of its western side. In this way the quarry was converted into a pool, which redirected runoff water to supply other pools beyond the northern line of the wall.

The enclosure wall is attached to the southwestern side of the watchtower, and exhibits a similar construction technique to the tower but is built of smaller stones. The southern line of this wall, partially built upon bedrock, is the only section preserved for its entire length, to a height of up to c. 6 m. At the second story level are nine small windows that provided illumination for the large rooms. The collapsed center of the western enclosure wall was rebuilt only in the twentieth century, when the land became agricultural. From photographs in the British archives, construction protruding from the path of the wall could be discerned at the southwestern corner of the site, apparently the location of the local latrine.

The enclosure was entered through two gates. One, found in the southern wall, is still complete, at 1 m wide and 1.9 m high. In the center of the front of its lintel is an incised cross. Above the lintel is a relieving arch made of massive stone. Six bolt sockets were fitted in the doorposts, three on each side. It is probable that this gate remained locked most of the time, and was used only as a rear escape route. A narrow corridor leads from the entrance northward to the center of the enclosure.

A second gate, uncovered during the excavations, was found in the center of the northern enclosure wall, of which nothing remains. Only a 2-m-wide threshold survives from this gate, which leads into the courtyard by way of a wide corridor with a coarse, white mosaic floor. North of this opening, an ancient road was identified, partly cut and stepped, and connecting the site with the main crossroads to the north.

The southern wing abuts the enclosure wall. Prominent in this wing are two large rooms (10 by 8 m) separated by a narrow corridor (3 by 3 m). They are built of ashlars and are well plastered. Their entranceways are narrow (1 m) and located close to the corners of the rooms at both ends of the corridor. Old photographs from the site indicate that three vaults once stood in the southeastern room, a room identified in the British archive as an olive-oil press. There is some evidence indicating that the wing had a second story, such as the plaster in the rooms and the small windows in the enclosure wall. The westernmost room of the wing, a small square room (7 by 7.5 m), has another room below it and according to photographs, another above it. Therefore, the building was at least three stories high in the southwestern corner of the enclosure. The southern wing appears to have contained the dining room, kitchen, and storerooms.

The large central courtyard, the dimensions of which are not quite clear, was paved in a coarse white mosaic floor. A hewn staircase connects the yard to the entrance of the watchtower. The courtyard was enclosed from the north by a number of dwelling rooms which have not yet been excavated. The major changes of phase B occurred in the yard. Its area was reduced and it was subdivided into additional rooms by fieldstone walls built directly on the mosaic floor. A chapel was erected in its center, and in the southeast corner, at the foot of the watchtower, a roofed winepress (5 by 5 m) containing a square plastered collecting vat was constructed.

The long, narrow chapel (25 by 8.5 m, wall thickness 0.9 m) is well constructed, partially of ashlars. The entrance (2.2 m wide) is in the west, of which only a threshold survives. The anteroom or “narthex” is narrow (6.8 by 2.7 m) and is paved in a colored mosaic floor with geometric and diamond-shaped motifs. It is bordered on the east by a stylobate of smoothed stones, at the ends of which are well-dressed stone columns. The northern column (2.5 m long and 0.6 m in circumference) was found lying on its side.

The nave (13.3 by 6.8 m) features a large, colored mosaic floor (10.5 by 5.5 m), framed by rope-like patterns and divided in its middle into alternating stylized squares and circles. Badly damaged by later agricultural activity, only fragments of the mosaic were found in the excavation. A low wall, the remains of a chancel screen (not found in the excavation), separates the hall from the bema; in the middle of this wall, stone steps and a narrow (0.9-m-wide) opening lead up to the bema floor, which is not preserved aside from a section of colored mosaic, in the shape of a bow, facing the opening. On the eastern side of the bema is the apse, 5.5 m wide, well built of ashlars, preserved four courses (about 2 m) high, and plastered on its inner side.

Due to topographical limitations, the two rooms which normally would have been built on either side of the apse were both erected north of the apse. Entry to the rooms was by two narrow (1–1.2-m-wide) openings cut into the wall to the north of the chapel. Their walls are plastered and their floors paved in mosaic: the eastern room’s mosaic is a white panel decorated in red diamonds and squares, the western room’s is more ornate and colorful, with geometric motifs. The artistry, size, and color of the tesserae, as well as the motifs and decorations, date the mosaics of the chapel and the side rooms to the sixth century CE. Repairs to various parts of these mosaics are dated to the eighth century CE.

CONCLUSIONS

The location of the complex close to a crossroads of secondary routes together with its imposing construction and sizeable watchtower lead to the conclusion that it was financed and built by the local lord. The site belonged to a group of neighboring villages that led a campaign of land-grabbing and control of inner roads in southwest Samaria and north Benjamin, a policy which gained momentum toward the end of Roman rule in the Land of Israel. During the 6th century CE, parallel with the strengthening of Christianity as the state religion, the Land of Israel once again became a center of events and the local authorities renewed the call for the taking hold of lands. For this purpose, a group of monks was introduced into the existing territory. Deir Qal‘a changed from a military compound to a civilian-Christian site under the patronage of the authorities. In making the site more amenable to its new inhabitants, the chapel was built and the pool system was upgraded so as to supply the monastery and surrounding agricultural lands. This settlement continued until the early eighth century CE, at the beginning of the Early Islamic period. The Arab conquest and the strengthening of Muslim rule in the Land of Israel led to the ultimate abandonment of the site.

YITZHAK MAGEN, NAFTALI AIZIK

THE SITE

Deir Qal‘a (or Deir Kulah) is located at the edge of a precipice, 370 m above sea level, on the northern banks of the Shiloh River, southwest of the Peduel settlement and some 1.5 km east of the village Deir Balut in western Samaria. Its elevated position afforded it control over the surrounding area and several junctions of secondary roads that crossed the riverbed and connected southern Samaria and northern Benjamin with the Coastal Plain.

EXPLORATION AND EXCAVATIONS

Deir Qal‘a is mentioned frequently in historical sources, often described as a Byzantine monastery due to the remains of a chapel found at the site, along with building stones bearing incised crosses. The nineteenth-century scholar V. Guérin describes an impressively fortified monastery and dates its founding to the fourth–fifth centuries CE. Early twentieth-century British surveyors, the first to map and draft a plan of the site, characterize the finds as a fortified castle and monastery of the Byzantine period. The 1968 survey of Ephraim and Manasseh suggests that this was a large manor house of the same period, a proposal supported by contemporary scholars and surveyors. Three seasons of excavations were carried out during 2004–2005 by Y. Magen and N. Aizik of the Staff Officer for Archaeology in Judea and Samaria, with the purpose of clarifying the connection between the fortified building and the chapel and other Christian remains at the site.