‘En Ḥofez

THE SITE

The site of ‘En

EXCAVATIONS

Archaeological excavations of an approximately 1-a. area were carried out at the site in 1994 by Y. Alexandre on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, prior to the construction of a new residential area in southern Yoqne‘am Ilit. The site had suffered damage by mechanical digging. Subsequent to the excavations, part of the site was released for development; another unexcavated part was covered by fill and developed as a park. Three major periods were exposed: the Middle Bronze Age, the Iron Age, and the Persian–Hellenistic periods.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE. A domestic building measuring 13 by 10 m and oriented north–south was uncovered directly beneath the extensive public building complex of the Persian–Hellenistic periods in the northwestern part of the excavated area. The building, built directly on bedrock with fieldstone walls preserved up to six courses (c. 1 m), consists of six rooms with floors, doorways, and thresholds. Beaten-earth floors, sometimes plastered, created level surfaces on the uneven bedrock. There were two superimposed floors in most of the rooms, indicating an extended period of use. An infant burial was discovered beneath the lower plastered floor in one of the rooms, adjacent to one of the two doorways of the room. On the upper floors of the building were found several smashed pottery vessels, including bowls, pithoi, and a collection of about 30 large baked clay loom weights. The pottery is dated to the Middle Bronze Age IIA–B. There is no sign of violent destruction by fire, but the quantity of pottery and loom weights at the site suggests that it was suddenly abandoned.

THE IRON AGE. An extensive Iron Age settlement was partially exposed at the site, alongside but not overlying the Middle Bronze Age dwelling, and below the major Persian–Hellenistic complex. Since the later Persian–Hellenistic walls were generally not dismantled during excavations, the Iron Age plan is not fully understood. However, the one that emerges is of several houses built according to a radial plan, oriented differently than the later Persian orthogonal plan. There is evidence for a cobbled alleyway between two houses and another two houses share a wall. The plans of the individual houses are not uniform, but a basic four-room concept, including pillared partition walls and three-room variants, may be discerned. The houses have inner courtyards, side rooms, and backrooms, separated by fieldstone walls preserved to a height of up to six courses (c. 1 m), and connected through doorways with stone thresholds. The floors are of beaten earth and occasionally of flagstone, and there is evidence for three superimposed floors in several of the rooms. The rooms are furnished with clay ovens (tabuns), stone installations for oil pressing, and an unidentified mud-brick installation. On the uppermost floors was found a domestic repertoire of Iron Age IIA–B pottery (tenth–ninth centuries BCE), including bowls, cooking pots, storage jars, and stone querns. In one of the rooms three dipper juglets filled with silver pieces and simple silver earrings were discovered, intentionally buried beneath a corner of the uppermost floor. The pottery repertoire indicates that the settlement was abandoned sometime in the ninth century BCE.

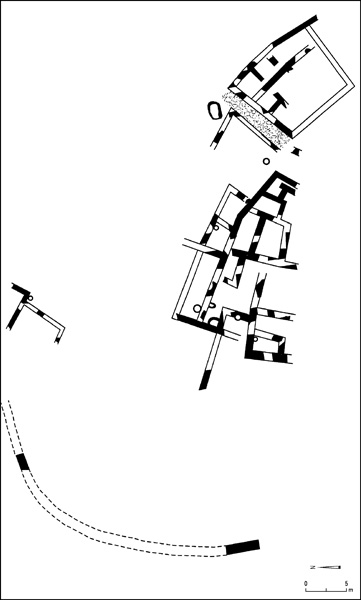

A small trial square, excavated about 30 m east of the main excavation area in order to investigate the eastern limit of the Iron Age settlement (outside that shown on the plan), exposed wider walls (1.0 m) than those of the houses (0.7 m). On the basis of the width of these walls, their orientation, and their location at a slightly higher level than the ground to the east, it can be suggested that the walls were part of an Iron Age fortification system. Two other small sections of walls (1.0–1.1 m wide) uncovered on the southern and southwestern sides of the excavated area may be part of the same defensive system.

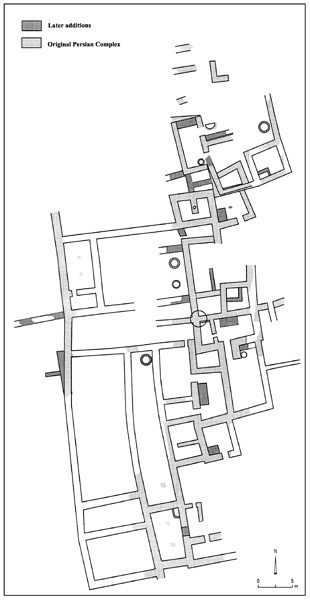

THE PERSIAN AND HELLENISTIC PERIODS. A major building complex with dimensions of at least 80 by 60 m was erected at the site during the Persian period. Only part of the complex was excavated, as the eastern part lay beyond the limits of the salvage excavation. Moreover, since part of the excavated area was destroyed by mechanical digging, it was not possible to fully reconstruct its plan. A long 1.0 m-wide stone wall with no entryways was exposed for a length of c. 30 m on the western side, and was probably the external wall of the complex. A similar adjoining wall was uncovered on the southern side. Overall the complex exhibits an orthogonal plan and required leveling works at the site in order that it be constructed on a fairly uniform level.

Within the outer walls, the complex is divided by stone walls (c. 1.0 m wide) into rooms or units of varying sizes, of which roughly 30 were exposed. They include large rooms, smaller rooms, small storage rooms, and open courtyards. The larger rooms, c. 7 by 4 m, have extant pillar bases for two pillars each to support the roofing. The walls, built of large and medium-sized stones, are preserved for five to six courses to a height of over 1 m, often employing a herringbone masonry technique. There is widespread evidence for changes and repairs throughout the complex, in the form of added walls and installations, superimposed floors, and blocked doorways. Several of the units have evidence for three superimposed floors of flagstone or packed earth. The rooms and the courtyards included large ovens, stone installations possibly for oil pressing, stone-lined storage bins, and several stone millstones and grinding stones. A stone-built, well-plastered bath was found in the corner of one of the large rooms.

The enormous pottery assemblage in the complex consists of hundreds of storage jars, predominantly sack-shaped jars and some large basket-handled jars. Three whole carinated “torpedo” jars datable to the beginning of the Persian period were found beneath the floor and walls of the complex, in a room defined by wall stubs, thus providing a terminus post quem for the construction of the complex. Other pottery vessels include mortaria with flat and ring bases, bowls, cooking pots, juglets, lamps, and several imported vessels such as amphorae, Cypriot juglets, and East Greek black-glazed ware. An unusually large number of iron tools were discovered in the complex, including a plough, a plough ring, many sickles, and pick axes. Several of these objects were found hidden in the stone walls of the building, unusual contexts suggestive of a sudden abandonment of the site by its occupants. The few weapons at the site include several iron knives and daggers, and one iron and one bronze arrowhead. A unique group of six bronze Hellenistic long-nozzled lamps with partly smelted receptacles and several lumps of slag were exposed in one room. Bronze smelting was apparently one of the activities that took place in the complex. Luxury artifacts include a bronze mirror, a bronze ladle, a bronze eagle figurine (possibly a weight), a miniature incised stone incense altar, bronze fibulae, and a couple of miniature faience or paste amulets. Among the coins are a few miniature bronze Tyrian coins and one bronze and one silver coin of Alexander the Great, the latter two originating from the uppermost level, which reflects the latest use of the complex.

The construction of the complex must postdate the three carinated torpedo jars, which belong to the late sixth or early fifth century BCE. It continued in use, having undergone a series of alterations, as late as the time of Alexander the Great. The bronze lamps with their distinctly Hellenistic long nozzles certainly belong to the final phase of the complex. The architecture, furnishings, agricultural tools, and other finds in the complex clearly indicate that it was a well-planned public building, constructed and controlled by a central authority. The activities that took place in and around the complex included large-scale agriculture and food production and storage, and at one stage, bronze smelting. Several items in the ‘En

THE MAMELUKE AND LATER PERIODS. An undated enclosure built of huge stones reflects a later occupation of the site, subsequent to its abandonment. Apart from this enclosure, later graves—probably from the Mameluke period—were dug into the stone walls of the complex.

YARDENNA ALEXANDRE

THE SITE

The site of ‘En