Gerizim, Mount

HISTORY

Archaeological finds—pottery, coins, and radiocarbon dating—indicate that the temple on Mount Gerizim was first built in the mid-fifth century BCE. A city began to grow up around it at the end of the fourth century BCE, after the city of Samaria was destroyed by Alexander the Great. At the beginning of the second century BCE, in the days of Antiochus III, the temple and its compound were rebuilt and the city expanded greatly. Based on the coins found at the site, it is clear that the temple and the city were destroyed by John Hyrcanus around 110 BCE, and not in 128 BCE as recounted by Josephus, who writes that immediately after the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes (128 BCE), Hyrcanus launched a campaign against Mount Gerizim (Antiq. XIII, 254–257; War I, 62).

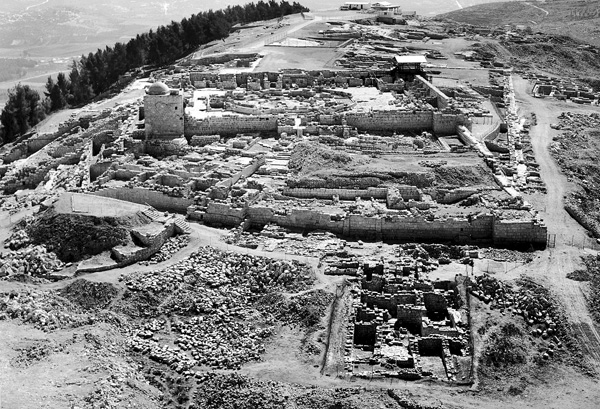

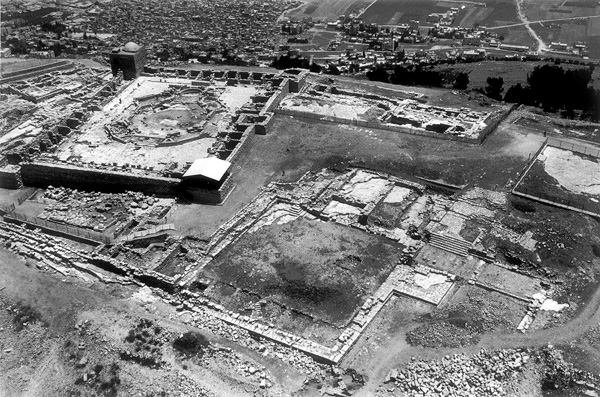

The city and temple stood abandoned through the Hasmonean and Roman periods, during which the Samaritans made a number of unsuccessful attempts to reestablish their control of the mountain (Antiq. XVIII, 85–89; War III, 307–315). During the reign of Antiochus Pius (160 CE), the upper temple of Zeus on the northern ridge of Mount Gerizim was inaugurated, and at the beginning of the third century CE, the temple was completed by one of the Severan Dynasty. At the beginning of the fourth century, with the rise of Christianity, the Samaritans reconstructed the sacred precinct and converted it into a pilgrimage site. In the Late Roman period, a fortress was erected near the precinct. In 484 CE, Zeno erected a fortified church to Mary Mother of God on the ruins of the sacred precinct. The church was reconstructed and expanded by Justinian after it was damaged in the Samaritan revolts. During the Crusader period the Samaritans successfully returned to Mount Gerizim to conduct sacrifices; a monumental Samaritan inscription was found from this period.

EXCAVATIONS

Excavations at the site, under the direction of Y. Magen, began in 1983 and continued for 20 years until 2003. Large parts of the Hellenistic city and the Samaritan sacred precinct were uncovered in the excavations. The Byzantine period Church of Mary Mother of God and its compound on the southern ridge and the remains of the temple of Zeus to the north were excavated by R. J. Bull.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

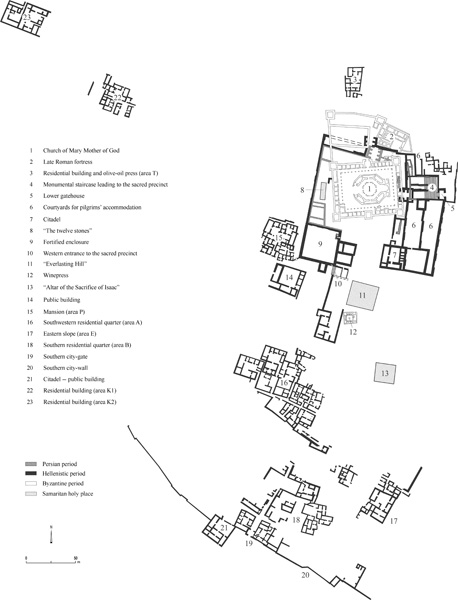

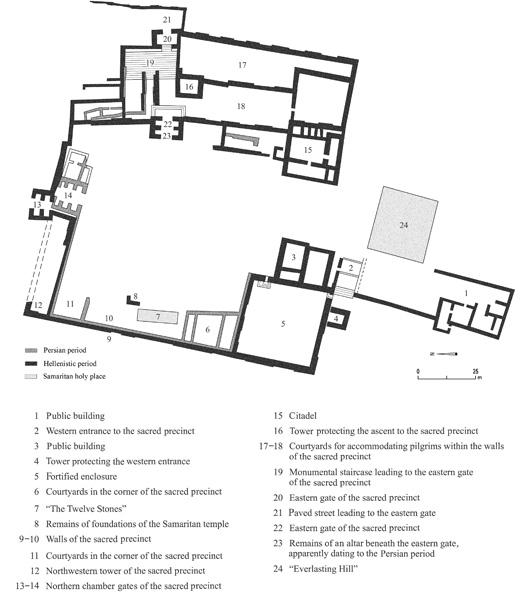

The archaeological discoveries on Mount Gerizim can be divided into the Hellenistic city, the sacred precinct from the Persian period, the sacred precinct from the Hellenistic period, the Roman temple of Zeus, the remains to the north of the Roman temple, the renewed Samaritan cult on the mountain in the fourth century CE, and the Church of Mary Mother of God.

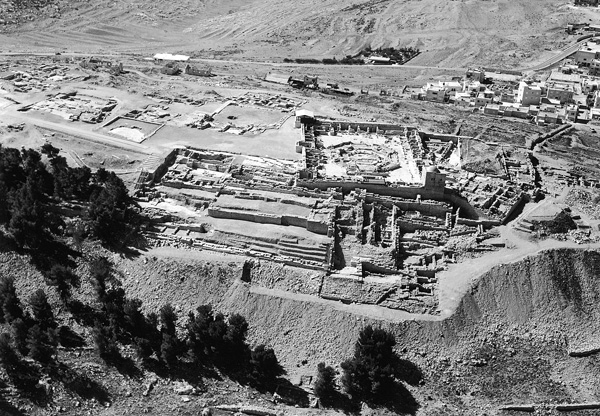

THE HELLENISTIC CITY. The Hellenistic city grew up around the sacred precinct of the Persian period, which was built on the highest spot of the southern range of Mount Gerizim, overlooking Shechem and the eastern valleys. Two major roads reached the city. One ascended from Shechem to the west through a pass to the Roman temple. The other, from the east, is the extension of the route to Shechem from Jerusalem in the south. The city founded on Mount Gerizim had no natural advantages, having been built on a high, barren mountaintop with no water sources, far from the central crossroads of Samaria. It was established for religious reasons at a holy site and functioned as a sanctuary and city of priests.

The city covered an area of 800 by 500 m—over 100 a. Most of the dwelling quarters were situated on its southern and western sides, where the rocky terrain slopes moderately. Few buildings stood on the northern side, and construction on the steep eastern slope required large-scale hewing into the bedrock, with very few buildings constructed there as well. The city was not entirely surrounded by a wall and its perimeter was not determined by walls and towers. No urban planning is apparent. It grew and expanded slowly with the addition of buildings, streets, and neighborhoods. During the Hasmonean campaign against the city, the lack of a defensive wall necessitated the construction of barricades and the individual fortification of streets and houses. The only truly fortified area in the city was the sacred precinct erected during the second construction stage in the Hellenistic period.

The city was divided into residential quarters: the southern quarter (area B), which was the largest, including the citadel to the south of the city (area G); the southwestern quarter (area A); the mansion (area P); the eastern slope (area E); the northern quarter (area T); and the northwestern quarter (area K).

The Southern Quarter (Areas B and G). The densely inhabited quarter at the southern edge of the city is surrounded by an improvised peripheral wall formed by the adjoining walls of the outer houses. The quarter measures c. 300 m from east to west and c. 120 m from north to south and was traversed by a central road which began at the two-chambered southern gate (8.50 by 7.50 m) and ended at two large squares. Alleyways leading to houses branched off to the east and west. On either side of the gate stood two sizeable public buildings, each constructed around a central courtyard. The western building measured 19.30 by 16.50 m; the eastern building measured 21 by 17 m and had two entrances, one from the north and the other directly from the city gate. At the southwestern end of the southern boundary wall formed by the outer walls of the houses protruded a large citadel measuring 25 by 25 m and constructed around a central courtyard. All the exterior openings of the gate structures and the citadel had been blocked, apparently at the time of the siege of the city. To the northeast of the city gate was uncovered another group of buildings, which included buildings B1 and B2. B1 comprised a central building surrounded by storerooms; B2 was a large building with a central courtyard and an elaborate reception room, its façade adorned by two Doric columns, forming a portico.

The southern section of the boundary wall of the quarter was uncovered for 250 m. At its eastern end were enclosed courtyards. Some 180 m to the south of the boundary wall a fort (28 by 27 m) with four square towers (7 by 7 m) was revealed (area G), situated in a mountain pass along the road ascending to the city from the east. The finds inside the fort were few, but include coins from the end of the fourth century BCE up to the days of John Hyrcanus.

The Mansion (Area P). To the west of the sacred precinct, a large mansion was uncovered, unlike any other structure found as yet on Mount Gerizim. This architectural complex, built on a steep slope, was composed of three wings: an olive-oil press (building I), a dwelling and commercial section (buildings II–III, V), and luxurious living quarters (building IV). Measuring 40 by 40 m, the complex has five entrances—two in the north, one in the east, one in the west, and one in the south. It was constructed abutting the wall of the sacred precinct and in certain places has been preserved up to its second story.

Building I (22 by 19 m) was built around a paved court. The entrance, from the northern passage, had a well-hewn stone threshold into which was set a wooden door. In the large eastern hall a crushing installation and two niches for anchoring the beams of an olive-oil press were found, with weights still in situ. This building may originally have been a dwelling, which was converted into an olive-oil press at a later stage, similar to the building in area T (see below). To the west of the press was a luxurious dwelling, building IV, outstanding in the Hellenistic city on Mount Gerizim. It measured 20 by 14 m and was built around a stone-paved central courtyard with a cistern. The entrance was from the northern passage. This building had a magnificent reception room (13 by 5.5 m) with walls covered in stucco and colored frescoes, and a floor in white plaster. This is the only example of colored frescoes known so far on Mount Gerizim, suggesting that this building belonged to a wealthy individual. To the south of the olive-oil press was uncovered a group of buildings (II–III, V), including dwellings, storerooms, and shops that opened onto another passage to the south of the complex.

The Eastern Slope—“The Bakers’ Fort” (Area E). The eastern side of the city was characterized by steep slopes that hindered the construction of houses. As the Seleucid authorities did not permit fortification of the city, these steep cliffs could not be exploited for defensive purposes. Instead, large public buildings were erected to great heights, creating a wall of sorts. On the eastern slope to the south of the sacred precinct, two buildings were excavated, E1 and E2. The former was a large building, 42 by 25 m, apparently a public structure rather than a dwelling, given the absence of large cisterns. On its northern side a staircase descended eastward from the sacred precinct, measuring 8 m long and 2 m wide, and including 15 steps, all preserved intact. The staircase led into a vestibule which opened onto the central courtyard surrounded by dwelling rooms and a central reception hall on the western side. The building contained over 20 cooking and baking ovens and was therefore dubbed “The Bakers’ Fort.” E2 was a smaller building located on the upper eastern slope.

THE SACRED PRECINCT. The Samaritan sacred precinct, the first building erected on Mount Gerizim, was constructed in the mid-fifth century BCE (the Persian period) on the highest point of the mountain. In the second century BCE, at the beginning of the reign of Antiochus III, the temple and its enclosure were rebuilt following their destruction by John Hyrcanus.

The Persian Period Compound. The dimensions of the Persian period compound were 98 by 96 m, including the gates. The 1.30 m-wide western wall is preserved to a height of 2 m along its entire length of 84 m. Despite the easy access to the site from the west, no gates were uncovered in this wall due to the location of the holy of holies at the rear of the temple (which can probably be identified with the present-day Samaritan holy site known as “the twelve stones”). The western wall was built of large fieldstones hewn from the upper layers of bedrock, as opposed to the stones of the later Hellenistic compound, which were hewn from deep quarries. Enclosed courtyards stood at either end of the western wall. The southern courtyard measured 21.5 by 12 m; the northern courtyard was 2.5 m wide, its length unknown. The northern compound wall was completely uncovered, measuring c. 73 m long and at its center a six-chambered gate, 15 by 14 m. To the east of the gate stood a large building (12 by 11 m) in which thousands of burnt bones of sacrificial animals were found in a thick ash layer. This building, located next to the altar, may have served as a receptacle for ash from burnt sacrifices. The eastern wall of the compound was extensively damaged by later building in the Hellenistic and Byzantine periods. The eastern gate of the Persian period may also be assumed to have been six-chambered, like the one in the north, with a staircase leading up to it. Many finds from the Persian and early Hellenistic periods were preserved in this spot. The southern gate was also almost completely destroyed by Hellenistic construction.

Thus, in the Persian period compound there were apparently three gates, on the northern, eastern and southern sides, reminiscent of the temple described in the Book of Ezekiel as a model for the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Thousands of pottery vessels and Persian period coins were found in the sacred precinct, providing the mid-fifth century BCE founding date for the temple. It and the surrounding compound continued in use for c. 250 years until the construction of the new temple in the Hellenistic period.

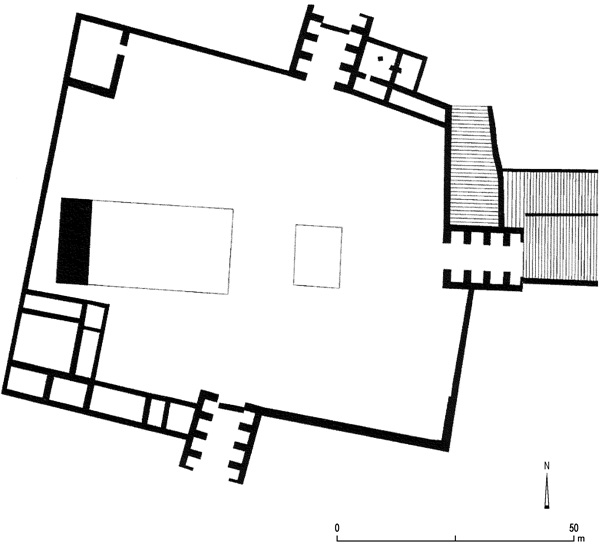

The Hellenistic Period Sacred Precinct. At the beginning of the second century BCE, a large, magnificent new compound was built in the sacred precinct, at its center a temple of white ashlars. It existed for some 90 years until its destruction by John Hyrcanus. (The precinct remained abandoned until the fifth century CE, when the construction of the Byzantine church and enclosure destroyed the Hellenistic compound to its foundations, with only its outer walls surviving.) In the Hellenistic period significant changes were made to the original plan of the precinct. For one, it was not modeled after the temple in Jerusalem, but followed a different style incorporating elements of Greek architecture. Although the core of the compound retained its original size, buildings and fortifications were added around it, increasing the outer circumference of the enclosure, which now measured 212 by 136 m. The western wall of the compound remained as it was, but a plastered offset-inset wall was adjoined to its outer face. The southern wing of the compound was drastically altered, with the addition of large public buildings and a monumental 9 m-wide staircase, seven steps of which are preserved, changing the direction of the entrance to the compound. The stairs led to a paved square, from which one turned north toward the temple. Opposite the staircase was a square tower, 9 by 8.5 m, built to defend the gate. The entrance to the sacred precinct was also protected by a fortified enclosure, 39 by 38 m, with 3 m-thick offset-inset walls, entirely plastered. To the south were large public buildings connected to the temple and used by visitors. The northern wall of the compound was preserved for its entire length, together with the northern gate. The Hellenistic offset-inset wall adjoined the earlier Persian wall from the outside. In the northwestern corner stood a fortified tower built of large stones. The earlier, six-chambered northern gate was now replaced by a small but elaborate four-chambered gate. The entrance was 3.60 m wide and each chamber, measuring 3 by 2.5 m, was well paved in stone slabs. This gate was built to the north of the earlier gate to provide access to the compound during construction. It was 10 m long.

The eastern wall, 93 m long, was built on the steep slope. In the center was a large, four-chambered gate measuring 14 by 10 m with an entrance 4.7 m wide. The northeastern corner was built of especially large stones set deep into the ground. At the southeastern corner of the compound stood a large citadel, 25 by 24 m, with very thick walls rising to a second story, perhaps a third. The citadel was built around a central courtyard containing an elaborate and well-preserved reception room. The eastern wing of the compound was fortified by two thick, offset-inset walls forming large courtyards, in which pilgrims gathered prior to ascending to the temple.

The eastern gate served the pilgrims visiting the temple from Shechem. A paved street, up to 16 m wide, led southward to a two-chambered lower gate. From here, a staircase, up to 23 m wide and 34 m long, rose the 15.5 m to the upper levels by way of some 57 steps. It was enclosed on its northern and southern sides by thick walls and a monumental watchtower. At the top of the staircase was an elaborate, four-chambered upper gate with two wooden doors whose copper hinges were preserved in situ.

THE FINDS. Hundreds of thousands of finds were uncovered in the excavations at Mount Gerizim, including some 16,000 coins, pottery vessels, stone vessels, glass vessels, metal objects, inscriptions, and over 400,000 bones of sacrificed animals.

Coins. Sixty-eight coins were found from the Persian period, prior to the conquest of Alexander the Great, including Sidonian and Samaritan coins, most coming from the sacred precinct. The earliest coin is dated to 480 BCE. From the Ptolemaic period, 417 coins were found, including issues of Alexander the Great and Ptolemy I to VI. A yhd-type coin dating to 270–285 BCE was discovered. Most of the coins found on Mount Gerizim date to the Seleucid period, to the reigns of Seleucus II and III, and Antiochus II–VIII. Also found were many Acco coins. As mentioned above, Mount Gerizim was not destroyed in 128 BCE after the death of Antiochus IV, but in 110 BCE during the reign of Antiochus IX. From the Hasmonean period, 546 coins were recovered, dated to the reigns of John Hyrcanus, Aristobulus, and Alexander Jannaeus. There is a break in the numismatic record at Mount Gerizim from after Jannaeus until the beginning of the fourth century CE, but numerous Late Roman, Byzantine, Late Islamic, and Crusader period coins were retrieved.

Animal Bones. In the sacred precinct at Mount Gerizim, over 400,000 burnt bones of sheep, goats, cattle, and pigeons, most below the age of one year, were found within layers of ash. The main concentrations of burnt bones were found in the following locations: on the northeastern side of the compound near the northern gate, most of these dating to the Persian and Ptolemaic periods; outside and along the eastern wall of the compound; in the fortified enclosure in the southwestern corner, near the western staircase; and on the inner, southwestern side of the Persian compound, near the “twelve stones.”

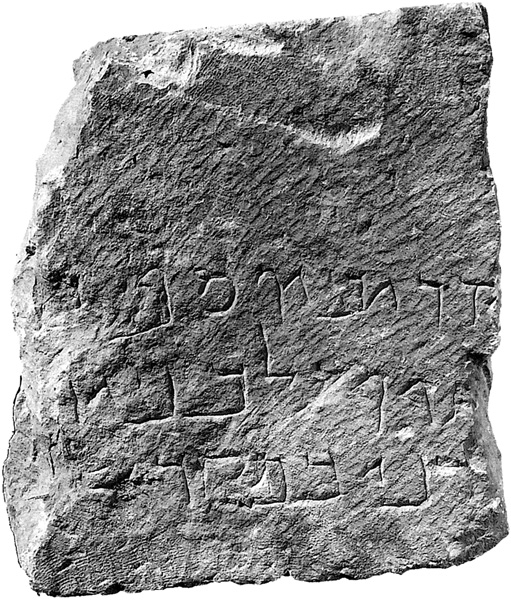

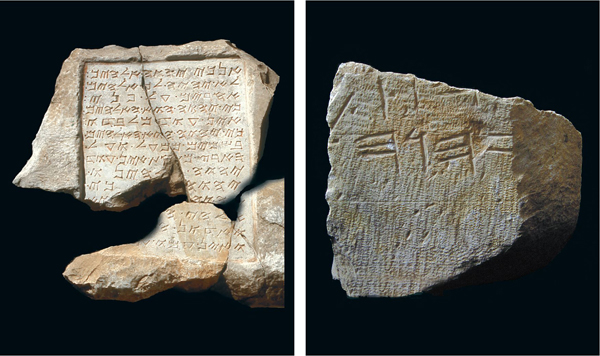

Inscriptions. Recovered in the sacred precinct of Mount Gerizim were over 500 inscriptions, as well as masons’ marks on building stones, paving stones, and a sundial. Some 400 inscriptions in ancient Hebrew and Aramaic are dated to the Hellenistic period. Most of the names mentioned, in addition to the titles of Cohen and Levite, are biblical Hebrew names. Eighty-three of the inscriptions are in Greek, some from the Hellenistic period; but most Samaritan dedications to the temple on Mount Gerizim are from the fourth and fifth centuries CE, when the Samaritans restored the sacred precinct. A few are from the Byzantine church. An inscription written in Samaritan script can be dated to the Crusader period. Over 20 ashlars, apparently from the temple itself, bear Hebrew and Greek masons’ marks.

Weapons. Many weapons were found at the site, including lead sling projectiles, bronze arrowheads, and a complete iron sword.

EVIDENCE FOR A TEMPLE ON MOUNT GERIZIM. Many of the finds from the sacred precinct indicate the presence of a temple on Mount Gerizim during the Persian and Hellenistic periods. The excavations revealed dozens of well-cut ashlars, bearing masons’ marks, which had been removed from the walls of the temple. Its large stones were reused in the church, and proto-Ionic capitals belonging to the early temple of the Persian period were found. The inscriptions discovered on Mount Gerizim provide the strongest evidence for the existence of a temple there. These include, for example, the titles of the priests who served in the temple and the formula qdm ’lh’ b’tr’ dn’ (before God in this place), indicative of the site’s sanctity. Another inscription includes the formula qdm ’dny (before the Lord), and an additional clearly legible inscription in Hebrew reads “that which Joseph offered for his wife and his sons before the Lord in the temple.” Another inscription mentions byt

THE SAMARITAN SACRED PRECINCT IN THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CENTURIES CE. Following the disappearance of paganism and the designation of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, a religious reform was initiated by the Samaritan leader Baba Rabah. The Samaritans took advantage of this time of transition to renew their cult on the sacred precinct on Mount Gerizim and construct many synagogues. Evidence for the existence of the Samaritan holy site on Mount Gerizim during the fourth century CE can be found in the Christian sources of the period and in Midrash (Bereshit Rabah 32:10). It is unknown whether there was only a synagogue for prayer or if animals were also sacrificed inside the Samaritan sacred precinct, as in the Hellenistic period. Dozens of Samaritan inscriptions in Greek have been found at the site. Most begin with the formula “the one God who helps” along with the Samaritan Hebrew names of those who dedicate gold coins to the holy site on Mount Gerizim.

YITZHAK MAGEN

Color Plates

HISTORY

Archaeological finds—pottery, coins, and radiocarbon dating—indicate that the temple on Mount Gerizim was first built in the mid-fifth century BCE. A city began to grow up around it at the end of the fourth century BCE, after the city of Samaria was destroyed by Alexander the Great. At the beginning of the second century BCE, in the days of Antiochus III, the temple and its compound were rebuilt and the city expanded greatly. Based on the coins found at the site, it is clear that the temple and the city were destroyed by John Hyrcanus around 110 BCE, and not in 128 BCE as recounted by Josephus, who writes that immediately after the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes (128 BCE), Hyrcanus launched a campaign against Mount Gerizim (Antiq. XIII, 254–257; War I, 62).