Ha-Bonim

IDENTIFICATION

Ha-Bonim is located 1 km inland from the Mediterranean coast, 15 km north of Caesarea, and 7 km south of ‘Atlit (Kfar Lam). The remains of a small, trapezoidal castle are situated atop a kurkar coastal ridge, c. 30 m above sea level.

Yaqut al-Rumi (c. 1179–1229 CE) referred to the site as Kafr Lab in a geographical gazetteer compiled in 1224/1225 CE. He dated the castle’s construction to the caliph Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik (724–743 CE). Frankish sources from between 1200/1201 and 1262 CE contain several references to the site. They never mention a castle, but refer to an estate (Latin casalibus or Old French casual) sold or exchanged among the lords of Caesarea and the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, or among the latter and the Order of the Temple.

EXPLORATION

V. Guérin surveyed the site in 1841 and provided the first published description of it in 1875. He described a large enclosure flanked by semicircular towers and assigned its construction to the Crusader period. The site was subsequently visited and described by C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener within the framework of the Survey of Western Palestine. P. Deschamps (1939) accepted V. Guérin’s dating. In the early 1970s, new studies by M. Benvenisti and A. Kloner considered reassigning its construction date to the Early Islamic period.

EXCAVATIONS

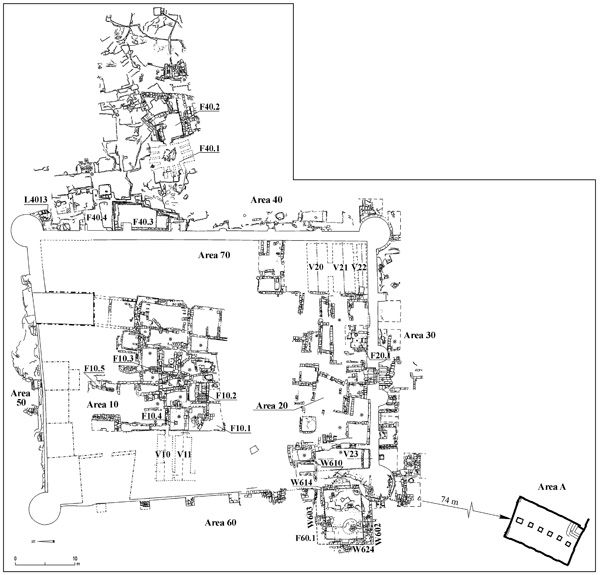

The excavations at ha-Bonim were conducted in 1999 on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, under the direction of H. Barbé and Y. Lehrer and with the assistance of M. Avissar. Three main excavation areas were opened inside the castle: area 10 at its center, area 20 along its southern side, and area 70 along its eastern. Outside the castle, work was conducted over a total of 4.5 a. in area 30 along the rampart’s southern face and in front of the gate, in area 40 to the east, and in area 60 to the west. Area 50, along the castle’s northern outer face, was not explored, since the rampart’s foundations there lie directly on bedrock.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

REMAINS PREDATING THE UMAYYAD PERIOD. Remains of the following periods preceding the construction of the castle were uncovered at the site: Chalcolithic (area 60), Persian and Hellenistic (areas 30, 40), and Roman and Byzantine (areas 10

Outside the Castle. A tomb (F40.1) comprising one room with a bench (3.80 by 3.40 m) and containing 12 loculi sealed by slabs was excavated. It was closed by both a flat stone door and a rolling stone and was approached via a pre-existing quarry. The inner end of each loculus was elevated with a pillow-like headrest, indicating the orientation of the burials. Anthropological analysis of the remains confirmed that the loculi had been used for multiple burials. Interred in the tomb were at least 54 individuals. Accompanying finds consisted of Byzantine pottery and glass vessels from the end of the fourth to the fifth centuries CE. A late Byzantine refuse dump (F40.2) in the quarry concealed the entrance to the tomb. The dump contained thousands of pottery fragments, including over 60 Samaritan lamps, mostly complete, and one late Byzantine–early Umayyad period lamp. Two coins minted in the sixth century CE and a “Byzanto-Arab” coin were the latest numismatic finds associated with this dump.

Another large quarry was uncovered to the east of the rampart (F40.3); quarrying activity undoubtedly predated the rampart, as the quarry extended westward below the rampart masonry. The rampart’s foundations were stepped inside the quarry, directly on bedrock, whereas the base of the nearest buttress overlay the fill in the quarry. The lower layers of the fill contained pottery sherds dating to the Persian and Hellenistic periods, which could be when the stone quarrying activity took place. The finds in the upper layers of the fill, at the elevation of the buttress, were dated to the transition from the Byzantine to the Umayyad period. Noteworthy among them are six Byzantine period lamps and an early Umayyad period lamp. The remaining layers of the fill contained sherds from the Early Islamic, Crusader, Mameluke, and Ottoman periods.

At the bottom of the western rampart, where the rampart meets the southwestern tower, c. 48 sq m of bedrock was exposed. A homogeneous layer of earth (0.30–0.40 m thick), including some early remains such as Chalcolithic pits, had accumulated on the bedrock. Overlying it was a dense mixture of lime and crushed shells, its composition similar to that of the mortar used for the construction of the castle. It appears that the mixture, used to create a flat surface or floor outside the rampart, was prepared in this area. It contained pottery fragments from the Byzantine to the Umayyad period and a coin dated 498–538 CE. The fill above this floor was dated to the Abbasid period.

The lime floor was also found outside the western end of the southern rampart. Most of the rich material below it there was dated to the Persian and Hellenistic periods, but also associated with it were several fragments of Byzantine period oil lamps and a few Abbasid pottery sherds. The floor rested on top of the rampart’s stepped foundation and abutted the rampart’s exterior base. Above the floor, all the fills outside the rampart and associated with it were contemporary with or postdated the Abbasid period.

Inside the Castle. A drain was discovered in the southwestern corner of the central excavated area (F10.1); the sherds in its fill dated to the Roman period, including two fragmentary discus lamps produced in the first to third centuries CE and a coin of Trajan (98–117 CE). A floor of the castle’s first building phase, composed of an earth and lime mixture and containing some Byzantine pottery fragments, overlay the fill in the drain. Over the floor were several later floor layers. They were composed of slabs and mortar and sealed the fills in the bedrock cavities, which contained finds dating to the transition from the end of the Byzantine period to the beginning of the Early Islamic period, including a Samaritan lamp of the seventh–eighth centuries CE. Finds from the Abbasid period were found upon these floors.

A quadrangular water reservoir was located immediately east of the drain (F10.2). Its bottom part and four steps in its southeastern corner were rock-hewn; the walls were coated with hydraulic plaster. The mosaic floor, composed of large white tesserae, suggests a Byzantine installation, most likely a winepress. When the upper walls of the vat were built on the bedrock, the stairs became obsolete, indicating a possible change in use of the original installation. To the north, the early floors of the castle were built in accord with the outer face of the reservoir. Other water installations excavated in the central excavation area include two rock-hewn cisterns, pear shaped and coated with hydraulic plaster (F10.3, F10.4), which contained finds indicating their abandonment in the Abbasid period.

At the northern side of this central excavation area, a drain (c. 5.00 by 1.50 m) built on bedrock was excavated (F10.5). Its walls were lined with dry masonry that supported the rectangular cover slabs. Thin layers of dark earth in the drain attest to sedimentation in still water; they contained finds from the Roman to the Early Islamic periods. Further to the north, on the same axis, an outlet was inserted in the outer face of the rampart. The level of the covering slabs embedded in the hard sediment corresponded to that of the castle’s early floor (30.79 m). The pottery in the hard sediment was dated to the late Byzantine–early Umayyad periods. Found together with it were a coin (498–538 CE) and a fragment of a Samaritan lamp(type 4).

All these data favor a construction date for the castle in the Umayyad period.

THE UMAYYAD CASTLE. The castle (southern façade 46.60 m; eastern 62.80 m; northern 51.40 m; western 60.00 m) occupied an area of c. 0.75 a., though the inner space did not exceed 0.5 a. The rampart’s thickness (1.60 m) could only be measured on the southern and eastern sides. A small portion of the northern wall, where it abuts the northeastern tower, was 2.20 m thick. The rampart had four solid circular corner towers (diameter of the southwestern tower 6.00 m; diameter of the other three 5.20 m) and two smaller, solid semicircular towers flanking the pointed-vault gate in the southern wall (diameter 2.80 m). The gate was 2 m wide between the doorposts. Eighteen buttresses were set along the rampart: two to the south, four to the north, and six to the east and west, respectively. The buttresses were square (each side 1.40 m) and fairly equidistant (7.00–8.80 m apart).

All the architectural elements of the castle were systematically bonded, indicating a single phase of construction. The castle’s masonry consisted of kurkar ashlars, mostly laid as stretchers and bonded with lime mortar mixed with shell inclusions. Six vaulted rooms of uneven proportions were preserved along the inner face of the rampart. The building method of these rooms was rather heterogeneous, employing headers and stretchers. The stones were bonded with the same lime and shell mortar mix used in the rampart.

An underground hall 74 m south of the castle was partially accessible from the surface. The room was rectangular (11.50 by 7.00 m) and oriented north–northeast by south–southwest. Two lines of arches were set on a central row of pillars and atop the room’s walls. The foundations of the walls and the pillar bases were rock hewn; the upper section was built. The roofing was composed of rows of rectangular slabs resting on top of the arches (on the extrados). The entrance was in the southern corner of the room; four rock-cut steps descended to the floor. Two openings in the northern wall were eventually sealed.

THE ABBASID AND LATER PERIODS. Occupation continued during the subsequent periods, from the Abbasid period to modern times, and is characterized by an increased density of buildings inside and outside the fortified wall. In the Crusader period a church (F60.1) was erected against the southern end of the western façade of the rampart. In the Early Ottoman period some of the earlier buildings inside the castle were partly razed and a pavement was laid.

Outside the Castle. To the southwest of the outer face of the rampart, alternating thin layers of earth and ash were identified (over 1 m thick). This deposition seems to have begun in the Fatimid period and continued into the Crusader occupation and may indicate relatively lax maintenance of the rampart area; the ash layers may have been the result of the clearing of undergrowth by burning. Some buildings, such as the Crusader church, were constructed in these layers.

The church was rectangular (11.0 by 9.5 m) and abutted the western rampart, next to the southwestern tower. It was oriented east–west with an apse. The southern (W602) and northern (W603) walls (1.80 m thick) had a double facing and were built on a stepped foundation upon bedrock. The foundation trenches were cut into a thirteenth-century CE fill. The main entrance (0.80 m wide) was in the center of the western wall; a slightly narrower door was placed in the western part of the southern wall. A third door may have been symmetrically located on the northern wall, though this could not be confirmed, as the wall was destroyed down to the foundation level. To the east, W602 abutted the outer face of the southwestern tower, where it was preserved to a height of nine courses; W603 abutted the outer face of the rampart and rested on a buttress, which was either destroyed or its top removed to accommodate the wall. The eastern wall (W614), on either side of the apse (W610), was built of stretchers and preserved to a height of three courses; it rested on a stone fill, which was partly intrusive into earlier layers, and leaned against and was aligned with the face of the rampart, between the southwestern tower and the buttress to the north. The apse was preserved to a height of five courses and penetrated 1.50 m into the masonry of the rampart, after the rampart was partially dismantled; its construction technique was identical to that of W614. The floor of the church was missing, most probably dismantled as early as the Mameluke period; however, the stratigraphic analysis, as well as some architectural elements, enabled us to estimate its level. The plan of this building, its orientation, and the chronological data point to its identification as a church from the Frankish period (thirteenth century CE).

Inside the Castle. During the Early Ottoman period numerous walls of buildings that were added inside the castle were leveled and the area was paved, restoring it to its original use as a courtyard. This change could be seen in the southern end, near the gate, and in the center of the area. Both areas had fairly consistent elevations (32.25 m and 32.50 m, respectively). These pavements overlay fill that contained pottery fragments from the seventeenth to the eighteenth centuries CE, including tobacco pipes.

SUMMARY

The original plan of the Umayyad castle was a quadrangular rampart, strengthened by buttresses and solid towers. Vaulted rooms abutted the inner rampart face and opened onto a paved central courtyard with cisterns and reservoirs. The plan follows a tradition of Roman-Byzantine military forts, but incorporates additions and alterations of Islamic architecture.

External influences are noted, such as the concept of a solid tower accessible only via the rampart-walk, which recalls Sassanid architecture. Byzantine architects, working for the new local potentates, appear to have drawn a standard plan suited to the tastes, needs, and means of their clients. Similar buildings from the Early Islamic period are found in the region: the castles or fortified caravanserais at Qasr al-Hair al-Sharqi, Qasr al-Hair al-Gharbi, Qasr al-Kharana, and Mshatta, as well as the palaces at Khirbet el-Mafjar and Khirbet el-Minya (

During the Abbasid period, the castle was modified. Its environs appears to have been neglected during the Crusader occupation, when construction was carried out outside the rampart, including the building of a small church, indicating that the castle did not serve a defensive purpose at that time. This is corroborated by the fact that medieval written sources fail to mention a fortification here. As referred to above, in various acts recorded in the charters of the Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem, the site is called a casual or casalibus of Cafarlet, or in other words, a village.

During the Ottoman period, the changes within the rampart sought to recreate the original plan: a central courtyard surrounded by rooms built on the roof of earlier vaults. Subsequently, the castle was abandoned and villagers settled in its ruins, as described by nineteenth-century travelers.

HERVÉ BARBÉ, YOAV LEHRER, MIRIAM AVISSAR

IDENTIFICATION

Ha-Bonim is located 1 km inland from the Mediterranean coast, 15 km north of Caesarea, and 7 km south of ‘Atlit (Kfar Lam). The remains of a small, trapezoidal castle are situated atop a kurkar coastal ridge, c. 30 m above sea level.

Yaqut al-Rumi (c. 1179–1229 CE) referred to the site as Kafr Lab in a geographical gazetteer compiled in 1224/1225 CE. He dated the castle’s construction to the caliph Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik (724–743 CE). Frankish sources from between 1200/1201 and 1262 CE contain several references to the site. They never mention a castle, but refer to an estate (Latin casalibus or Old French casual) sold or exchanged among the lords of Caesarea and the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, or among the latter and the Order of the Temple.