Hazor

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

In 1990, 35 years after Y. Yadin began excavations at Tel Hazor, a renewed excavation dedicated to his memory commenced at the site and has been underway continuously every summer. The Selz Foundation Hazor Excavations in Memory of Y. Yadin are a joint project of the Philip and Muriel Berman Center for Biblical Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University, the Israel Exploration Society, and, until 2000, the Complutense University at Madrid. The renewed excavation is directed by A. Ben-Tor.

The excavations have three main objectives. First, they aim at assessing the stratigraphical, chronological, and historical conclusions outlined by the Y. Yadin expedition. Second, they explore several important issues not resolved by Yadin’s excavations. Noteworthy among these are chronological issues, including the rise of “greater Hazor,” the date of the fall of Canaanite Hazor, and the date of the Iron Age II fortifications (gate and casemate wall, the so-called “Solomonic Gate”), attributed by Yadin to the tenth century BCE; and the complete exposure of the structure investigated by Yadin and referred to by him as “the ‘palatial’ building of the Middle Bronze Age II,” the northeastern corner of which was discovered in 1958. The third objective of the renewed excavations is to preserve and partially restore some of the most important monuments uncovered, prevent their further deterioration, and help develop Hazor into an attractive site for visitors.

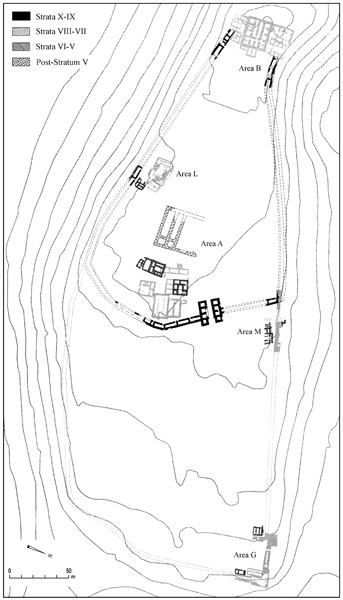

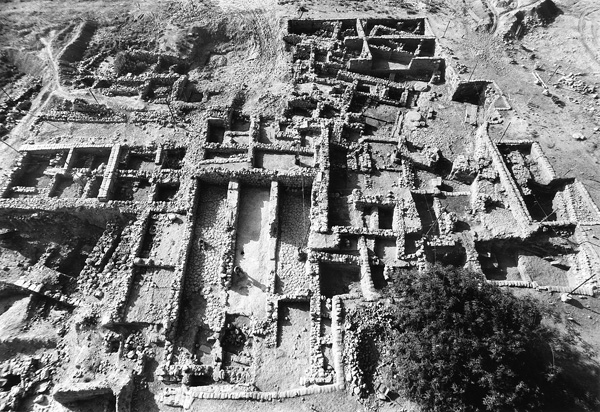

Whereas Yadin opened ten excavation areas in the upper and lower parts of the site, the renewed excavations opened only two, both of them in the upper city (the acropolis): area A, an expansion of Yadin’s area A in the center of the acropolis; and area M, on the northern edge of the acropolis, facing the lower city. In order to avoid confusion, it was decided to temporarily retain Yadin’s stratigraphic designations, despite the fact that as a result of the renewed excavations, it will be necessary to somewhat modify these designations, further subdivide various strata, and perhaps even add or omit strata.

The most complete stratigraphic sequence at Hazor was encountered in area A, where remnants of occupation from the Early Bronze Age through the Persian period were uncovered by the Yadin expedition. Also uncovered in area A were the “Solomonic fortifications,” the remains of the latest Late Bronze Age level, and what Yadin identified as the corner of Hazor’s Bronze Age palace. Hence, this area was chosen as the best place to attempt to check Yadin’s stratigraphy and chronological conclusions.

Area M is an expansion to the north and east of Yadin’s area M, opened in 1968. There were two main reasons behind the decision to return to this area. First, this is where Yadin’s excavations found the “joint” between the two major Iron Age fortification systems of the site, which he dated to the tenth and ninth centuries BCE, the reigns of Solomon and Ahab, respectively. It was one of the most disputed of Yadin’s chronological-historical conclusions, and it could be tested through work at this spot, along with the new information gleaned from the investigation in area A. The second reason it was chosen to work in area M has to do with the fact that the northern flank of the upper city (the acropolis) slopes steeply northward towards the lower city everywhere except in area M, at the middle of the slope, where there is a rather broad and flat terrace-like plateau. It was hoped that the investigation of this topographic feature might yield information on how the two parts of Hazor—the lower city and the acropolis—were connected.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

The following summarizes the results of 15 excavation seasons on the acropolis from 1990–2004.

THE BRONZE AGE. Monumental public buildings of the Bronze Age extend over the entire excavated area, in both areas A and M. This is explained by the fact that area A is located in the very center of the city’s acropolis, while area M is situated at the point of juncture of the lower city with the acropolis. The renewed excavations also exposed Bronze Age remains predating these monumental buildings.

An important addition to Hazor’s stratigraphic sequence is the discovery of remnants of a settlement dated to the Early Bronze Age IV (the Early Bronze–Middle Bronze Age transition). Remnants of walls belonging to modest dwellings, accompanied by ceramic assemblages including complete vessels of Early Bronze Age IV date, came to light in isolated spots in areas A-2, A-4, and A-5, where excavations reached sufficient depths. Yadin’s excavations suggested the existence of a settlement of that period at Hazor on the basis of sherds discovered in later fills (Yadin’s stratum XVIII). This Early Bronze Age IV village-type settlement is now a certainty.

No earlier architectural remains of the Early Bronze Age have yet been encountered by the renewed excavations, though such remains were exposed on a terraced surface in the area between the northern and southern temples during the 1968 season. A very large number of Early Bronze Age III sherds, many of them belonging to the Khirbet Kerak ware family, were found in the fill placed on top of the southern temple.

Two tombs found in area A-2 are noteworthy. One is an infant burial accompanied by clear Middle Bronze Age IIB burial gifts, thus earlier than the palace complex and perhaps also the A-5 fortifications. The second is a larger tomb, containing multiple burials and a bronze dagger; its pottery is of the same date as that of the other tomb. Both tombs seem to represent a stage of scanty occupation at the site (Yadin’s stratum Pre-XVII) prior to the full-blown building activity of Middle Bronze Age Hazor.

Probes below the southwestern corner of the throne room and in the courtyard of the Late Bronze Age palace in area A show that the palace was built on top of a thick fill intended to level the natural southwest–northeast downward slope of the site. The eastern wall of the courtyard (area A-4) retains the eastern edge of this fill, where it reaches a thickness of more than 2.5 m. Massive walls were found running westward below that fill and to the east, north, and south, beyond the limits of the later fill. The size of the walls and the narrow extent of the exposed area do not yet allow for the understanding of the plan of this very large structure. Furthermore, the walls suffered extensive damage due to stone robbing in later periods; the stones were probably used for the construction of the later palace. But the structure can be dated to the Middle Bronze Age: a series of floors associated with its easternmost wall bore a large assemblage of pottery of that period. It seems, therefore, that this massive structure, most of which is located under the floors of the Late Bronze Age palace, constitutes an earlier palace. If future excavations prove this conclusion to be correct, the occupant of this palace might therefore have been the Ibni-Addu mentioned in the Mari archive.

Another impressive architectural complex associated with this structure is of a cultic nature. It comprises a series of standing stones (

During the excavations conducted in the 1950s, a mud-brick construction more than 7 m wide was exposed (in trench 500). Yadin interpreted this as a wall belonging to Hazor’s fortifications, constructed in the Middle Bronze Age. In area A-5 of the renewed excavations, north of trench 500, a huge mud-brick structure was exposed, clearly a northern extension of the construction found in trench 500. This structure was filled in during the eighth century BCE, and buildings were constructed atop the fill. Due to its immense dimensions, the plan of this construction cannot yet be determined, but it can be said that it clearly dates to the Bronze Age. It was probably constructed in the Middle Bronze Age, and continued to be in use—at least in part—during the Late Bronze Age. Further excavations here may expose a city gate, and perhaps a citadel defending it. Due to the topography of the site, the approach to the upper city was always from the east, where it remains today. The Iron Age gate of the tenth century BCE and the approach to the expanded ninth-century BCE city were both on the east.

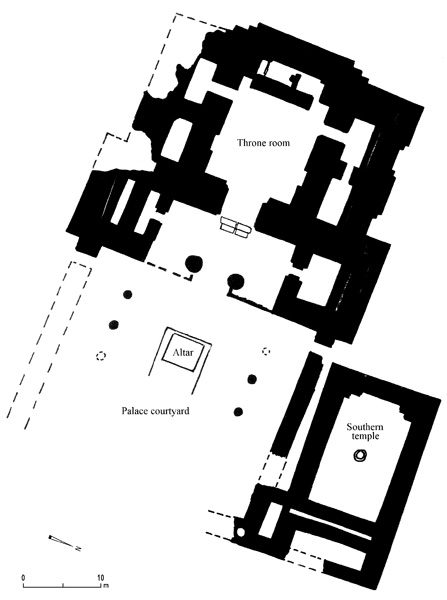

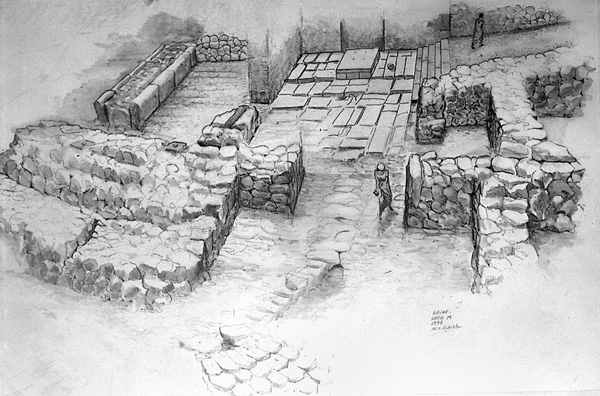

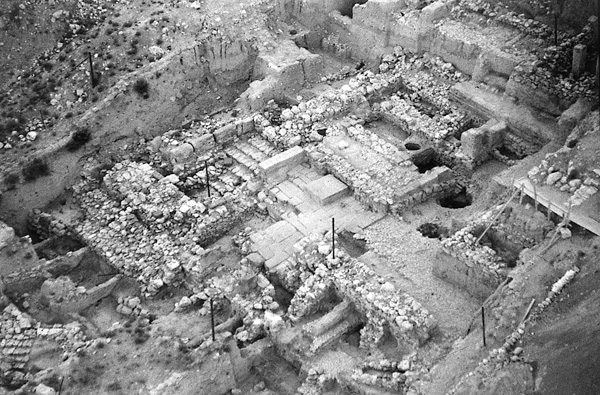

The huge remains of the Late Bronze Age palace (henceforth “the palace”) rise on the western edge of area A. It is composed of three main parts: the nucleus (consisting of the throne room and adjacent rooms), the porch, and the courtyard. The nucleus was so massively built that its walls still stand high, reaching the present surface of the site and forming a mound of their own. The level of the top of the walls of this Bronze Age structure is even today higher than that of the latest Iron Age houses built around it. With the exception of its southern flank and courtyard, this part of the palace was untouched by the Iron Age builders and thus escaped destruction. The administrative center of Iron Age Hazor, consisting of the tripartite storehouses and well-planned private dwellings, was built to the east of the nucleus of the palace, above its spacious courtyard. The area above the nucleus of the palace was left as an open “piazza.”

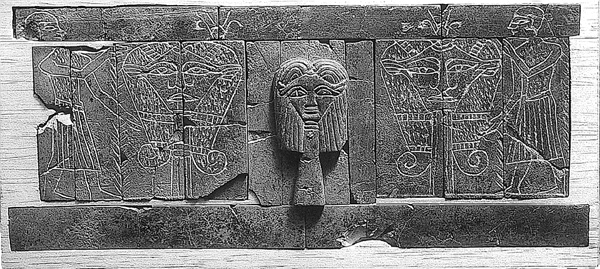

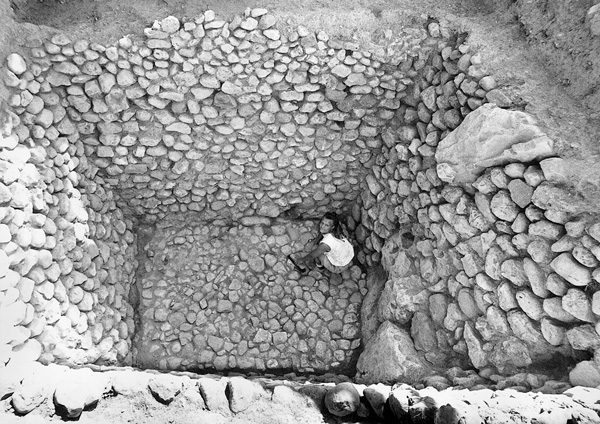

The walls of the main unit, built of mud brick resting on a stone foundation, are unusually massive, from 3–4 m thick. The lower part of these walls are lined, inside and out, by smoothly cut basalt orthostats. Wood played an important part in the construction. Wooden planks, mostly of cedar, were incorporated into the walls both horizontally and vertically; their charred remains were found in abundance. The throne room at the center of the unit measures c. 12 by 12 m. The wooden floor, which perished in the fire that destroyed the building, rested on a foundation of lime and pebbles, as indicated by two charred planks found lying on the pebble foundation. Further evidence for the wooden floor is the fact that the lower edge of the orthostats lining the lower part of the walls, originally concealed by the floor, are now exposed, ending some 15 cm above the pebble foundation.

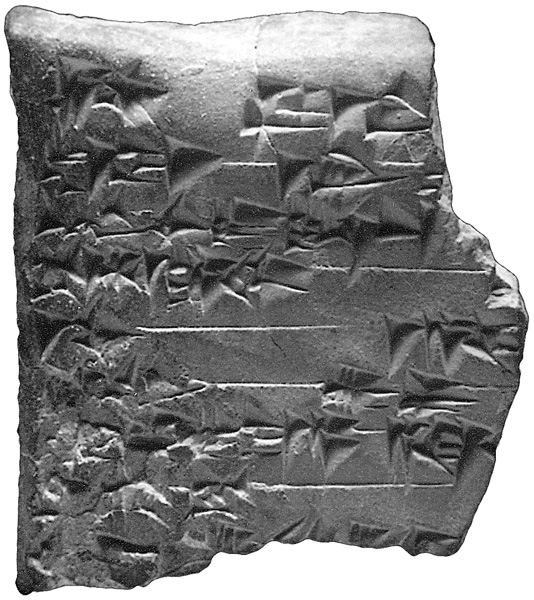

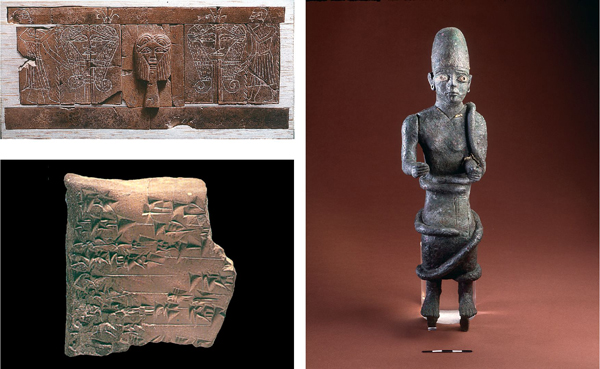

The plan of the palace very closely resembles that of the contemporary palace at Alalakh IV. This is manifest in the general plan of the courtyard, porch, and throne room; the similar approach from the courtyard to the porch; the corner location of the staircase; the broken zig-zag outer face of the walls; the orthostat lining; and the combination of wood and mud brick in the wall construction. The two buildings clearly belong to the same architectural tradition, another indication of Hazor’s northern affinities. The main difference between the two is that the Alalakh palace has numerous rooms, suited to its administrative role, while the Hazor palace has only five rooms flanking the throne room. However, it seems that despite this, the Hazor structure still merits the term “palace” (and not “temple,” which is another option), first and foremost because of its similarity in plan to the palace at Alalakh. Second, a structure that is clearly a temple lies in close proximity to the Hazor palace, and forms an integral part of the entire architectural complex. And third, the bathtub located in the rear room behind the throne room is another indication of the secular nature of the building. One should perhaps view the Hazor palace as more of a ceremonial edifice, while an administrative palace should be sought elsewhere on the site. The palace yielded the most impressive finds yet unearthed by the renewed excavations, including statues and statuettes of local and Egyptian origin; various works of art, among them the largest collection of decorated bone inlays yet found anywhere; and five inscribed clay tablets.

The large Syrian-type temple, termed the southern temple, lies immediately to the north of the courtyard. (A short distance to the north is another temple, the northern temple, uncovered by Yadin’s expedition in 1968.) Entered from the east, the southern temple is a long one-room structure with a recessed niche in the western wall, opposite the (presumed, but now destroyed) entrance. The southern stone-built wall still stands to its original height of nearly 2 m, its upper course entirely flat; the mud-brick superstructure was not preserved. The northeastern corner of this structure was already exposed by Yadin’s expedition in 1958, and was interpreted as the corner staircase of the Middle Bronze Age palace of Hazor. Now that the building has been exposed in its entirety, it is clear that a staircase indeed stood in this corner, but it was of the temple rather than the palace. The temple favissa is located in the very center of the structure and contained a large number of cultic vessels of various kinds, accompanied by ash and bones. When the building went out of use, it was covered to the top of its walls by a fill of earth mixed with hundreds of sherds, the majority of which date to the Early Bronze Age III, evidently brought from somewhere on the acropolis.

A pebble-paved street, which underwent several phases of repair, leads from east to west, having most probably originated at the city gate (not yet exposed, presumably located in area A-5). The street extends upward between the northern and southern temples, turns south along the western wall of the southern temple, and leads over a flight of stairs into the courtyard of the palace. This is a clear indication that all of these buildings are part of one master plan, and were in use or at least still visible at some point concurrently. The southern temple was constructed toward the end of the Middle Bronze Age (Middle Bronze Age IIC)—contemporary with the earlier (Middle Bronze Age) palace—while the later palace was probably built in the fifteenth or, more probably, in the early fourteenth century BCE.

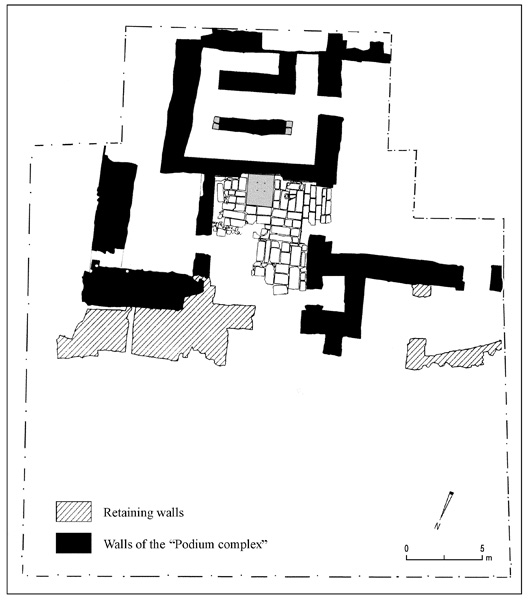

Less than 100 m to the north is area M, the junction between the lower city and the acropolis. A thick wall, only the stone foundations of which have been preserved, was exposed on the northern edge of the excavated area. This seems to have been an inner fortification separating the two parts of the town—the acropolis and the lower city—while at the same time serving as a retaining wall for the entire architectural complex to the south. A flight of stairs or a ramp, badly damaged by later Iron Age structures built upon it, leads southwards from the fortification up the steep slope, ending in an enclosure paved with smoothly cut orthostats clearly in secondary use. At the rear end of this enclosure is a square podium built of smoothed basalt slabs, its rear part placed in a shallow niche located in the northern wall of a building to the south. The cover stone of this podium is indented with four symmetrically placed depressions, which were most probably intended for a chair or throne upon which a dignitary was seated or perhaps a statue of a deity placed. A group of scoop bowls found strewn about indicates that some kind of cultic activity took place here, at the entrance to the acropolis. From here, a pebble-paved street or a huge courtyard, the continuation of which lies beyond the excavated area, leads upward toward the building located immediately to the south, and most probably also farther into the acropolis. The part of this building exposed so far consists of three long halls, lying side by side; its function is yet unknown.

Like the palace in area A, area M was violently destroyed in a huge conflagration that marked the end of Late Bronze Age Hazor. The date of this event is still a matter of controversy, and at this phase of the excavation no definite conclusion can be reached. Tentatively, however, it seems that this destruction of Hazor should be placed in the second or third quarter of the thirteenth century BCE, as indicated by the analysis of the ceramic assemblage associated with the destruction layer. Furthermore, such a date is supported by a fragment of an offering table found in area M, on which an inscription in Egyptian hieroglyphs mentions a high official (the name has not survived), whose title corresponds in form to those of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

THE IRON AGE. There was most probably a gap of occupation at Hazor between the destruction of the Late Bronze Age city and the Iron Age I occupation. The length of this gap depends on the date of destruction of Canaanite Hazor and cannot be determined at present. The Iron Age I (Yadin’s strata XII–XI) is represented by a few fragmentary walls found in areas A-1, A-3, and A-4, and by more than 30 pits, similar to those found by Yadin’s expedition at Hazor or known from other sites. These pits penetrate the destruction layer of the Late Bronze Age occupation. Most of the pits are round and unlined, c. 1.5 to 2 m deep. They are mainly filled with ash and characteristic Iron Age I sherds, dating to the eleventh century BCE. In no case are any walls, fragmentary as they are, superimposed upon or cut by the pits. Thus, in contrast to Yadin, we have no justification for ascribing two strata to these remains uncovered in area A.

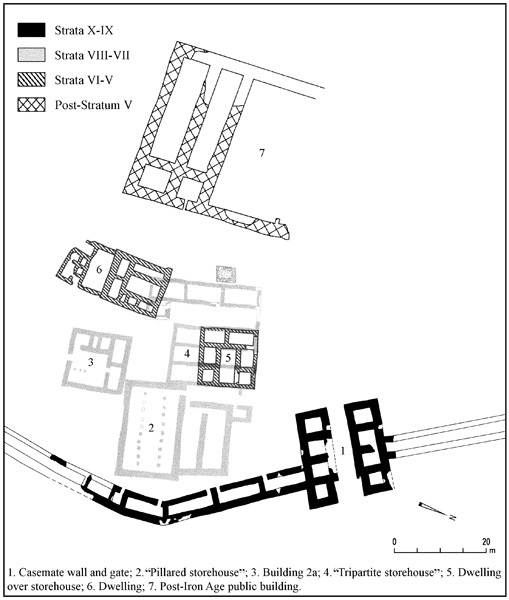

East of the administrative center (see below), an uninterrupted architectural sequence spanning strata X–V was excavated. Unlike the structures immediately adjacent to them, which are of a public nature, the structures in this part of the city are smaller and less well constructed. They seem to have functioned as private dwellings, shops, and installations of various kinds. This sequence is divided into many sub-phases, and, together with the sequence established in the administrative center, provides an important ceramic assemblage spanning the late tenth–late eighth centuries BCE.

Important data regarding specifically the tenth century BCE were uncovered in areas A-4 and M. A multi-roomed dwelling located immediately under the pillared storehouse of stratum VIII was exposed, yielding an impressive ceramic assemblage. The northern part of this building had already been exposed by Yadin’s expedition. Four architectural phases were identified, corresponding to Yadin’s strata XA–B and IXA–B. The earliest of these (stratum XB) is associated with the paved alley running along the inner face of the casemate wall, and thus also with the six-chambered gate. The ceramic assemblage originating in this dwelling dates to the late tenth century BCE and thus confirms Yadin’s dating of the defensive system. Additional support for this conclusion came from area M, where the northernmost room of the casemate wall, the excavation of which was begun by Yadin but not completed, also yielded a tenth-century ceramic assemblage on its earliest floor.

Iron Age Hazor reached its peak in the ninth century BCE (Yadin’s strata IXA–VIII–VII). Yadin’s excavations have shown that the ninth-century city was double the size of that of the tenth century. The expanded city area was fortified by a wall. Part of this wall, referred to as the “solid wall,” was uncovered in area M. The ninth century also saw the construction of the citadel (area B), the huge water system (area L), and the pillared storehouse (area A). The renewed excavations unearthed another tripartite storehouse, built concurrently with the pillared one, immediately to its west. Remnants of huge storage vessels, one of them complete, were found sunk into the floor of that storehouse. Two stone-lined silos dug into the ground, each with a capacity of c. 40 cu m, or some 60–70 tons of grain, were uncovered in areas A-1 and A-3 in close proximity to the storehouses. Immediately to the south and west of the storehouses are two buildings of the four-roomed type, one (building 2a) uncovered by Yadin and another by the renewed excavations; they probably served officials administrating this public area in the very center of Iron Age Hazor. At least one of them (building 2a) continued in use even after the storehouses were abandoned. A long, well-built hall, probably the northern third of a tripartite storehouse—most of which lies outside the excavated area—was encountered in area M.

A dense occupation represented by dwellings and installations dating to the eighth century (Yadin’s strata V–VI) was encountered in the entire area to the south and west of the limits of Yadin’s excavations in area A, as well as throughout area M. An important change in the architectural layout of the entire area was noted: the large public storehouses built in the ninth century BCE (strata VIII–VII) went out of use and were replaced by private houses. This is true also for the structure identified as a storehouse in area M. The main public storage space was then located in area G. Two circular silos dug into the floor of the courtyard of one of the dwellings encountered in area M may indicate that grain storage during that period was more commonly private than public.

Indications of the destruction of stratum VI by earthquake, noted by Yadin, were not identified. There is an evident decline in the urban layout of the city in the eighth century (strata VI–V) relative to the ninth century, when area A in the center of the town had been strewn with buildings of a public nature. However, the dwellings which replace the huge storehouses that once stood there still exhibit a degree of affluence. Mostly belonging to variants of the four-room house type, they are rather spacious domiciles, measuring c. 150 sq m each, and carefully planned and well built, as befits a neighborhood located at the very center of the city. The renewed excavations have defined more sub-phases in this period than were reported by Yadin, resulting in a very dense stratigraphic sequence for the tenth–eighth centuries BCE, unparalleled at any contemporary site in the country. The latest remains in both areas A and M (Yadin’s stratum VA) were found to have been violently destroyed and covered by a thick layer of ash and debris, clearly associated with Hazor’s destruction in 732 BCE by the Assyrians.

A few scattered walls associated with patches of floors encountered in areas A-1, A-2, and A-3 are later than this destruction layer. The meager ceramic assemblage associated with these walls, lying immediately below the surface, dates to the Iron Age and should therefore be ascribed to Yadin’s stratum IV. In area M these remains are much more substantial and include several complete architectural units. However, since there they are located mainly on the slope, outside of the Iron Age fortifications, they are not superimposed on the destruction layer of stratum V. It is therefore impossible to determine whether these too should be ascribed to stratum IV, or represent a stratum V occupation located outside the town’s fortifications. If the former is the case, then the settlement of stratum IV was much more substantial than Yadin estimated.

In the center of the acropolis, west of the palace complex, the remains of a very large structure were found, its dimensions indicating a public use. The structure was found destroyed down to below the level of its floors, with only its foundations surviving, which makes it difficult to arrive at a precise date for it. The fact that the building severs walls clearly associated with the late Iron Age settlement at Hazor (of Yadin’s stratum V) shows that it was erected after the destruction of Israelite Hazor. However, a more precise date than one sometime in the Assyrian, Persian, or Hellenistic periods cannot be arrived at presently.

THE PERSIAN–HELLENISTIC PERIODS. The cemetery of the Persian period, investigated by Yadin’s expedition in the center of the tell (area A), was confined to the area immediately to the west of the Iron Age gate. Not a single additional tomb of that period was found during the renewed excavations in area A. In contrast, the northern slope of area M, overlooking the lower city, was strewn with tombs of the Persian period, located mainly on the plateau in the middle of the slope.

Only a handful of stray sherds of the Hellenistic period were found in both areas of the excavation.

THE EARLY ISLAMIC–OTTOMAN PERIODS. Numerous sherds dating from the Early Islamic through the Ottoman periods constitute the latest indications for human activity at Hazor. Remnants of a building dating to the Ottoman period are still visible in the eastern part of the upper city; another one overlying the western wall of the pillared storehouse was excavated by Yadin; and parts of buildings dating to the Mameluke period were excavated by us on the southern edge of areas A-1 and A-4. The southern edge of the acropolis appears to have been occupied at that time.

Pockets of ash mixed with Gaza ware found on the southern edge of areas A-1 and A-4, and some fragmentary lines of small stones encountered in areas A-2 and A-3 (perhaps huts or demarcations for tents) are probably remnants of sporadic activity by the inhabitants of the village of Waqqas, which was situated to the east of the tell.

RESTORATION

Since the beginning of the renewed excavations, the following architectural units have undergone preservation and partial restoration: the cultic installation of the Iron Age I uncovered in area B of the Yadin expedition, the Iron Age I pits in the palace courtyard, the six-chambered gate and adjacent casemate wall, building 2a and the pillared storehouse (both relocated), the olive-oil press within building 2a, the podium and stairs in area M, the northern temple, and various parts of the palace. Under the direction of O. Cohen, the excavation conservator, a protective roof has been constructed over the palace nucleus.

AMNON BEN-TOR

Color Plates

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

In 1990, 35 years after Y. Yadin began excavations at Tel Hazor, a renewed excavation dedicated to his memory commenced at the site and has been underway continuously every summer. The Selz Foundation Hazor Excavations in Memory of Y. Yadin are a joint project of the Philip and Muriel Berman Center for Biblical Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University, the Israel Exploration Society, and, until 2000, the Complutense University at Madrid. The renewed excavation is directed by A. Ben-Tor.

The excavations have three main objectives. First, they aim at assessing the stratigraphical, chronological, and historical conclusions outlined by the Y. Yadin expedition. Second, they explore several important issues not resolved by Yadin’s excavations. Noteworthy among these are chronological issues, including the rise of “greater Hazor,” the date of the fall of Canaanite Hazor, and the date of the Iron Age II fortifications (gate and casemate wall, the so-called “Solomonic Gate”), attributed by Yadin to the tenth century BCE; and the complete exposure of the structure investigated by Yadin and referred to by him as “the ‘palatial’ building of the Middle Bronze Age II,” the northeastern corner of which was discovered in 1958. The third objective of the renewed excavations is to preserve and partially restore some of the most important monuments uncovered, prevent their further deterioration, and help develop Hazor into an attractive site for visitors.