Jezreel (Yizre’el), Tel

INTRODUCTION

Tel Jezreel (Yizre’el) is situated on a ridge extending along the southern side of the eastern part of the Jezreel Valley. The site rests at the edge of the ridge, some 100 m above the valley bed, commanding over the ancient highway between Megiddo and Beth-Shean, which passed through the valley. The mound is roughly rectangular, covering an area of c. 15 a. The Arab village of Zer‘in was located in the northwestern part of the site, its graveyards extending onto the southeastern part. Presently, only the Ottoman tower or small fort and the medieval church still stand, while heaped ruins of the Arab village, destroyed in the 1948 War of Independence, cover the surface.

The site and its surroundings contain many rock-cut cisterns, some still open today. Although their date cannot be established, it seems that rainwater collected in cisterns was the main water source of the settlement in ancient times. A large spring, ‘En Jezreel, is located in the valley to the northeast of the site. However, since it is relatively far away and situated at a lower elevation, it seems unlikely that it was the main water source of the settlement on the tell.

The site was continuously settled subsequent to the Iron Age, its ancient name reflected in the name of the Arab village, Zer‘in. Christian travelers who visited Jezreel in the twelfth century CE mention the tomb of Jezebel at the site. Benjamin of Tudela visited Jezreel c. 1165 CE, noting one Jewish dyer who lived there. In the fourteenth century

HISTORY

In the Biblical period, Jezreel is referred to in Joshua 19:18 in the context of the inheritance of the tribe of Issachar. In 1 Kings 4:12, it is mentioned in the list of districts governed by Solomon’s “officers,” indicating that the site was settled at the time of the United Monarchy. 1 Kings 21 tells the story of Ahab and Naboth, implying that Ahab built a palace in Jezreel, although it remains possible that the story refers to the palace and events in Samaria. 2 Kings 9–10 tells the story of Jehu’s revolt and his takeover of Jezreel in 842 BCE. It is clear that Jezreel was a royal center then, and that Joram King of Israel, the dowager Queen Jezebel, and Ahaziah King of Judah—all killed by Jehu—had been residing there. Jezreel is also mentioned in Hosea 1:4, possibly in reference to Jehu’s revolt.

In the Roman–Byzantine period, Jezreel is named twice. The anonymous pilgrim of Bordeaux referred to Jezreel in 333 CE as Stradela. In the Onomasticon of Eusebius, written in the fourth century CE, Jezreel is similarly mentioned as a large village named Esdraela, located between Legio and Beth-Shean. During the Crusader period, the settlement at the site was known as Le Petit Gérin, or Parvum Gerinum. It belonged to the Templars; Abu Shama hints that it may have been fortified. Zer‘in is mentioned several times in connection with battles of that period. It was conquered and destroyed by Muslim units in 1183, and burnt by Saladin in 1184. In 1187, it was overtaken for the final time by the Muslims. In 1263, the Franks negotiated unsuccessfully to gain back Zer‘in, and in 1283, Burchard of Mount Sion refers to Zer‘in as a village of 20 or 30 houses. In 1596–1597, the tax survey of Sultan Muhammad bin Murad III refers to four heads of households with taxable agricultural products at the site. In 1688, O. Dapper relates that the settlement at that time consisted of roughly 150 houses inhabited by Moors and Jews.

EXCAVATIONS

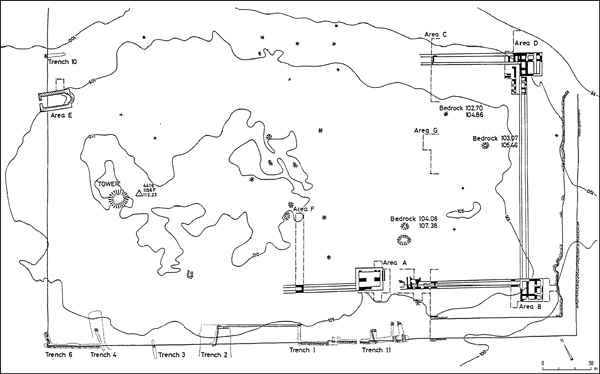

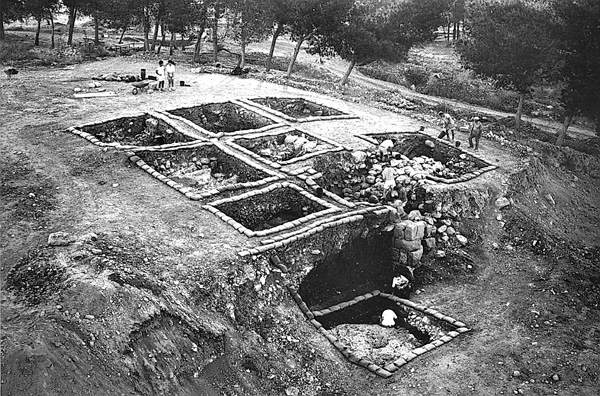

Several surveys have been conducted at Tel Jezreel and the medieval church. N. Zori surveyed the site as part of his Beth-Shean Valley survey. Another survey was conducted recently by M. Oeming. In 1987, it was decided to build a museum dedicated to the history of Jewish settlement in the Jezreel Valley in the area to the southeast of the site. Preparatory work by bulldozers discovered two corner towers of the Omride enclosure. The building plans were halted, and two salvage excavations were carried out by the Department of Antiquities, now the Israel Antiquities Authority. P. Porat, O. Feder, and S. Agadi excavated the area within the corner towers, and O. Yogev excavated on the slope to the southeast of the site. In 1990–1995, systematic excavations were carried out by D. Ussishkin and J. Woodhead on behalf of Tel Aviv University and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. Several sections were cut across the walls of the Omride enclosure, and two of its corner towers and the gate were excavated, as was the medieval church.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE EARLIER PERIODS. Early Chalcolithic (Wadi Rabah culture) flint artifacts and pottery, as well as Early Bronze Age pottery mainly dating to the Early Bronze Age III, were collected from the tell and its slopes. It is not clear whether the site was settled during these periods or that these finds had been brought from the site located near ‘En Jezreel. Late Bronze Age pottery uncovered in later fills does seem to indicate that a settlement existed at the site then.

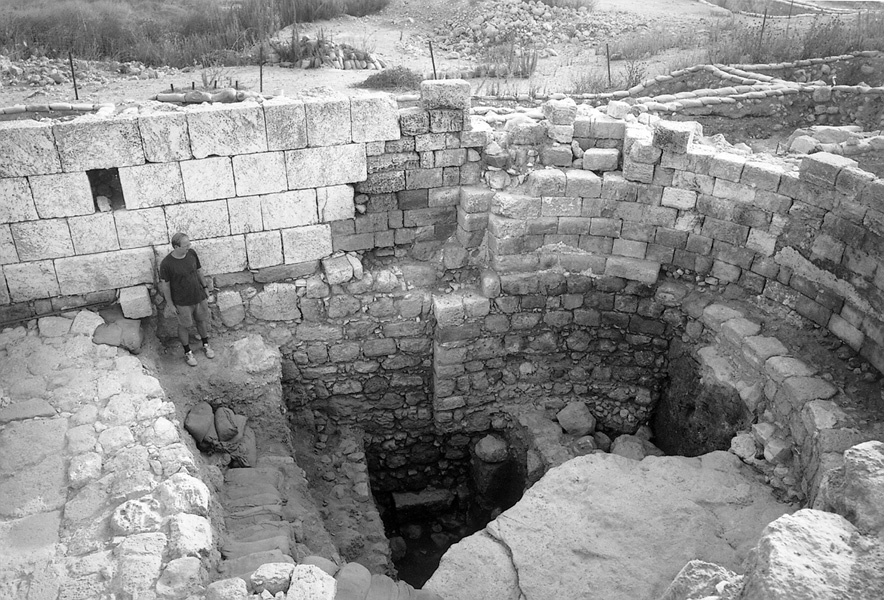

THE OMRIDE ENCLOSURE. Pottery found in the constructional fills of the Omride enclosure shows that the site was settled in the Iron Age IIA, however nothing is known of its size or character. Between 882–852 BCE, a large fortified enclosure was built by Omri and Ahab at Jezreel. Its construction is dated and assigned to the Omride kings on the basis of biblical evidence. It is a symmetrical, rectangular enclosure surrounded by a casemate wall with square projecting towers in its corners. The wall and the towers were buttressed on the outside by an earthen rampart. The lower interior part of the rampart was made of layers of brown soil, its upper exterior part of limestone chips and gravel. A rock-cut moat surrounded the enclosure on all sides except the northeastern, where the wall and ramp extended along the edge of the steep slope of the ridge. The moat, which is 8–12 m wide, is at present filled with later debris. Its bottom, 6.5 m beneath the surface, was reached in one spot. The impressive moat is unique in this period, and indicates the particular strength of the fortifications and the importance of the enclosure. The gate is situated off-center in the southwestern side of the enclosure. It is a six- or four-chambered gatehouse likely accessed by a bridge or drawbridge over the moat.

Much effort was invested in the construction of the fortifications. The enclosure was of massive proportions, 289 m long and 157 m wide, encompassing an area of c. 10 a. The overall length of the moat along three sides of the enclosure was c. 670 m. It was roughly estimated that the construction of the moat involved the hewing of c. 26,800 cu m of rock, and that some 23,300 cu m of soil and gravel was dumped to form the rampart.

Relatively little is known regarding the interior of the enclosure, as most of the excavations took place near the corner towers and the gate area. Bedrock is somewhat high in the central parts of the enclosure, requiring the dumping of soil brought from the vicinity in the lower parts to level the area. In the gate area, the fills contained debris taken from the earlier Late Bronze Age and Iron Age IIA settlements. Remains of two public buildings were uncovered near the gate and the eastern corner tower. In the chambers of the casemate wall and adjacent to them were found relatively poor domestic remains. The finds consist mainly of domestic pottery.

The fortifications were mostly preserved at foundation level. The walls are generally built of boulders laid in courses, with smaller stones filling the spaces between them. The superstructure of (at least) the southern corner tower was built of mud bricks. The use of ashlars is limited; several corners were built of them, but only some ashlars were incorporated into the walls.

No structural changes or phases have been discerned in the enclosure, an indication that it was in use for a relatively short period of time. The southern corner tower was destroyed by fire, a possible indication that the enclosure met its end in a willful destruction. This conclusion is also supported by one bronze and eight iron arrowheads found in the excavations.

THE LATER IRON AGE. Meager settlement remains were found above the ruined enclosure. They include pottery and two storage jar handles bearing lamelekh seal impressions. Four burials, one in a clay “bathtub” coffin, were uncovered near the ruined gate of the Omride enclosure, apparently part of an intra-mural graveyard.

THE LATER PERIODS. Settlement continued at the site, apparently without interruption, into the twentieth century. During the Byzantine period the entire site was settled, including the area of the derelict Iron Age moat. Several winepresses and other installations indicate agricultural activity. Rock-cut tombs dating to the Roman–Byzantine period were uncovered in the vicinity. During the medieval period, the settlement was limited to the northwestern part of the site. A church and a tower or small fort were built in this area in the Crusader period. Two structural stages were discerned during the excavation of the church, suggesting that it was founded in the Byzantine period. The remains of the tower were incorporated into the small fort built in the Ottoman period.

SUMMARY

A settlement existed in Jezreel during the Early Bronze Age III, Late Bronze Age, and Iron Age IIA, but the site rose to prominence when Omri and Ahab, reigning in 882–852 BCE, built a fortified enclosure there. Several proposals have been made regarding the role of Jezreel vis-à-vis Samaria as a royal center in the kingdom of Israel. J. Morgenstern suggested that Samaria was the summer capital and Jezreel the home of the royal winter palace. A. Alt believed that the Kingdom of Israel had two capitals, one for the Canaanite and the other for the Israelite population. Y. Yadin suggested that Samaria served as the capital of the kingdom, but that the temple of Ba‘al was built on Mount Carmel rather than Samaria, not far from Jezreel. H. Olivier was of the opinion that Samaria served as the capital, while Jezreel was a kind of “gateway city,” controlling the access to the Jezreel Valley from the east, as well as the hilly central regions of the kingdom.

Following the excavations, Ussishkin and Woodhead suggested that Omri and Ahab, who according to the written sources had a large army, built the fortified enclosure at Jezreel as a central military base and a strategically located military fort. The chariotry and cavalry units of the Israelite army were probably garrisoned at the site. Various buildings likely stood inside the sizeable leveled enclosure, including perhaps a royal residence. As stated, it is reported that shortly before Jehu’s revolt in 842 BCE, King Joram and the dowager Queen Jezebel resided at Jezreel.

The enclosure was probably destroyed during the campaigns of Hazael, King of Aram, during the later part of the ninth century BCE, as suggested by N. Na’aman. Following the destruction of the enclosure, Jezreel lost its importance but settlement there continued through the ages, apparently without interruption until 1948. The settlement in the Byzantine period was large and prosperous, covering the entire site. A medieval village from the Crusader period existed in the northwestern part of the site, where the remains of a church and a tower or small fort still stand. Later, the Arab village of Zer‘in was built there.

DAVID USSISHKIN, JOHN WOODHEAD

INTRODUCTION

Tel Jezreel (Yizre’el) is situated on a ridge extending along the southern side of the eastern part of the Jezreel Valley. The site rests at the edge of the ridge, some 100 m above the valley bed, commanding over the ancient highway between Megiddo and Beth-Shean, which passed through the valley. The mound is roughly rectangular, covering an area of c. 15 a. The Arab village of Zer‘in was located in the northwestern part of the site, its graveyards extending onto the southeastern part. Presently, only the Ottoman tower or small fort and the medieval church still stand, while heaped ruins of the Arab village, destroyed in the 1948 War of Independence, cover the surface.

The site and its surroundings contain many rock-cut cisterns, some still open today. Although their date cannot be established, it seems that rainwater collected in cisterns was the main water source of the settlement in ancient times. A large spring, ‘En Jezreel, is located in the valley to the northeast of the site. However, since it is relatively far away and situated at a lower elevation, it seems unlikely that it was the main water source of the settlement on the tell.