Judean Hiding Complexes

INTRODUCTION

One of the fascinating aspects of the Second Jewish (or Bar-Kokhba) Revolt against Rome is the extensive use of underground cavities and installations for hiding, escape, refuge, defense, and guerilla warfare. Two main types of caves can be distinguished—refuge caves and hiding complexes. The refuge caves are natural subterranean spaces found mainly in the Judean Desert, in the eastern slopes and cliffs of Judea overlooking the Dead Sea and the Jordan Valley (see Vol. 3, pp. 816–837). The artifacts found in them make it evident that they served as places of refuge for the inhabitants of the Judean Mountains and the Jordan Valley when they fled for their lives at the end of the Second Jewish Revolt. The archaeology of the caves has been studied and summarized by H. Eshel and D. Amit.

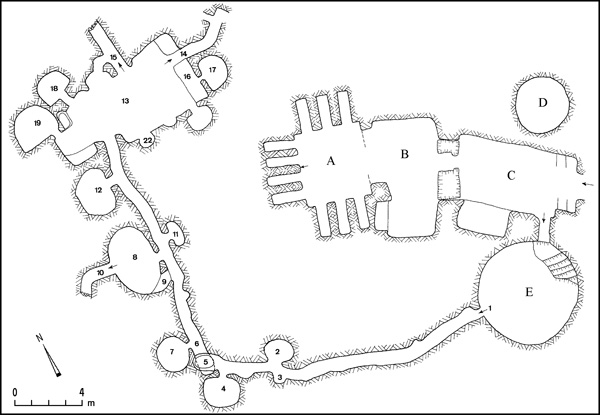

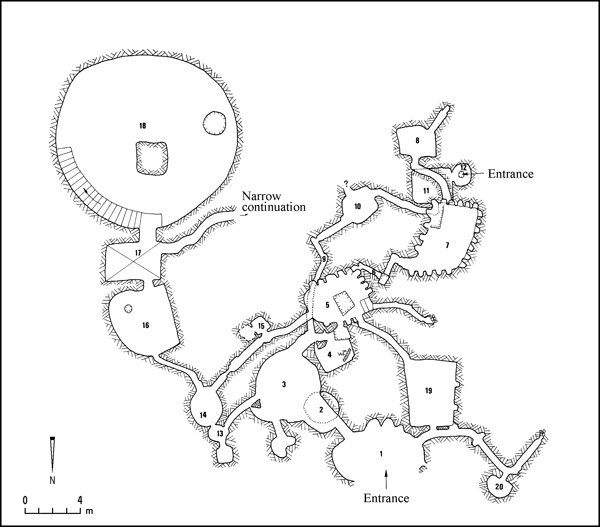

The hiding complexes, on the other hand, were artificial subterranean spaces, quarried under or near residential buildings in ancient settlements. They are found mainly in the Judean Shephelah, but also in the Hebron and Beth El Hills. They were usually cut out of the soft limestone, which is common in the Shephelah, but also out of the harder formations of limestone found in the mountainous regions. The majority of the complexes were completed prior to or during the Second Jewish Revolt. Recently, the dating of a few networks—mainly small, unsophisticated ones—has been moved up to the time preceding the First Jewish Revolt.

R. A. S. Macalister first documented complexes at Tel Azekah, Khirbet el-‘Ein, and Tel Gezer in the early twentieth century. The discovery and identification of hiding complexes in the 1970s was a breakthrough in the research of the Second Jewish Revolt. Those in the Judean Shephelah were first defined as such in 1978 by D. Alon. The phenomenon was investigated by teams led by A. Kloner and Y. Tepper, with the participation of the Israel Cave Research Center, and published in 1987. In the recent updating by B. Zissu in 2001, approximately 125 sites containing over 320 hiding complexes were identified, most of which contained typical indicators of Jewish presence such as stone vessels, mikvehs, and burial caves with ossuaries. It seems that the systems so far identified are but a small fraction of the original number. It can be estimated that on the eve of the Second Jewish Revolt, a total of c. 800–1000 Jewish sites, with one or more hiding complexes, existed in the Judean countryside. This number is consistent with the Roman historian Cassius Dio’s figure of 985 Jewish villages destroyed as a result of the revolt.

FEATURES OF THE COMPLEXES

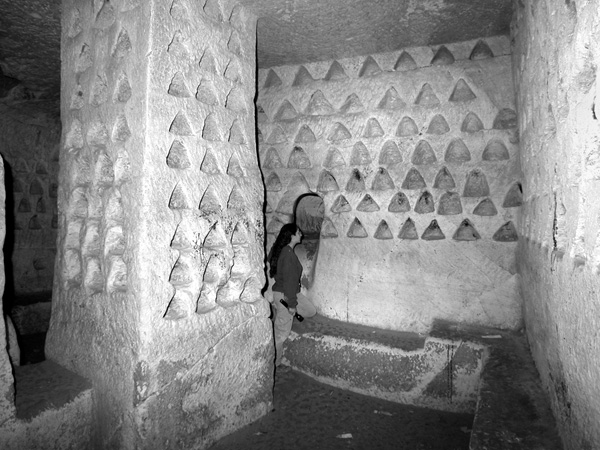

Most of the complexes were cut deep into the rock underneath residential buildings in ancient Jewish settlements; only a few were located outside settlements. In antiquity it was customary to hew underground chambers and installations underneath houses and in courtyards between houses for residents’ everyday use. These cavities, which formed part of the settlement’s infrastructure, were quite diversified in function, having been used as cisterns, ritual baths, olive-oil presses, storerooms, stables, columbaria, and underground quarries.

The creators of the hiding systems linked preexisting chambers by means of ramified networks of underground burrows. These burrows, a distinctive feature of the complexes, are narrow and low—requiring one to bend over or crawl—and winding, sometimes with 90-degree turns or changes in level by means of vertical shafts. Some of the burrows have mechanisms allowing them to be blocked from the inside. The purpose of the sharp turns, changes in level, labyrinthine layout, and blocking facilities was to hamper the enemy advance and render it vulnerable to attack. The narrow tunnels allowed only one enemy fighter to advance at a time and made it virtually impossible to use a weapon while holding a light source, putting the enemy at a distinct disadvantage vis-à-vis the defenders, who lay in wait. It thus neutralized the superiority of a military unit trained for face-to-face combat. The burrows also connect distant parts of the settlement and were sometimes used to flee the settlement.

Many of the underground complexes have standard features that suggest they were cut as part of a pre-planned military strategy used by the Jews against the Roman army. Extant underground facilities were exploited, their original openings sealed, and narrow shafts were carved and camouflaged in the floors of buildings and through the walls of underground installations, creating hidden shelters. Cisterns underwent similar processes: their upper, external openings were concealed, and the water was drawn through a burrow, from inside the hideout. Other spaces were created explicitly as hiding systems; these contain passages and small chambers and are not contiguous with earlier underground installations. The complexes as a group are quite varied in size and function, from small familial hiding facilities to intricate multi-branched complexes meant for public use. It is apparent that in many cases the systems were created as a last means of escape, as industrial installations were cancelled and cisterns and ritual baths were rendered unusable by passages cut through their walls, thus preventing the residents from continuing their routine economic life and daily activities.

DATING

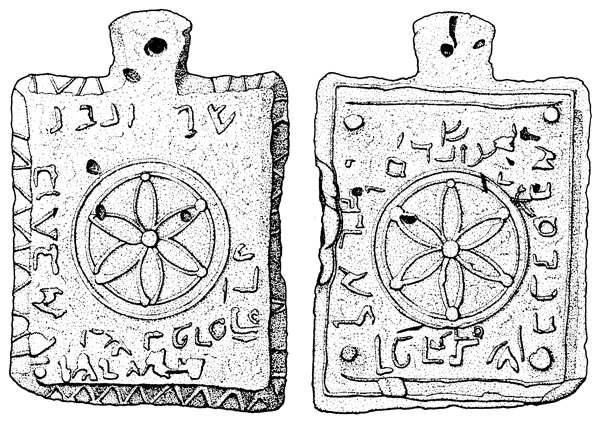

The dating of the hiding complexes is still unclear. The main obstacle is the near absence of data from controlled excavations. Most of the complexes had been broken into and looted before archaeological research was conducted in them, leaving few assemblages of finds to be recovered and published. Nevertheless, in the years since the publication of Kloner and Tepper’s research in 1987, extensive evidence has been found that the systems were indeed used during the Second Jewish Revolt. One of the most significant finds is a lead weight of the Bar-Kokhba administration found in the complex at

Historical sources also support dating the use of the hiding complexes to the time of the Second Jewish Revolt. The most important source is Cassius Dio, preserved in a later abstract, in which he reports that the rebels “…might meet together unobserved under ground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light.” The Church Father Jerome (fourth–fifth centuries

Some researchers have proposed dating the hiding complexes to the Hellenistic period, based on isolated pottery sherds from this period found in surface surveys and in a few hiding complexes. However, the actual finds were never published and their context is unclear. Early artifacts could have originated in preexisting facilities and cisterns that were included in the hiding systems, and therefore cannot be considered as evidence for an early date of the system, and certainly not of the entire phenomenon.

In a complex at ‘Ain ‘Arrub, excavated by Y. Tsafrir in 1973, a mixture of artifacts dated from the Persian through Ottoman periods was discovered. A rich assemblage of artifacts from the late Second Temple period to the Second Jewish Revolt comprised pottery sherds, fragments of glass vessels, and coins. The system had been looted over the years and its stratification disturbed. The exact date of the burrow linking two large, presumably preexisting underground chambers is difficult to determine.

Excavations conducted in 1999 by B. Zissu and A. Ganor at

A shekel from the second year of the First Jewish Revolt was found in an underground complex below the synagogue at Khirbet Susiya, suggesting that this chamber was hewn and used before the Second Jewish Revolt. A hoard containing 777 prutot from the second and third years of the First Jewish Revolt, found by Tepper and Kloner in a niche in the floor of a passageway leading out of a chamber in the Khirbet Zeita system, supports the assumption that parts of the hiding complexes and the hewn caves were used during this revolt.

G. Foerster has pointed out that at least some of the passages and burrows described by Josephus in his accounts of people hiding in caves in the Galilee during the First Jewish Revolt may be hiding complexes. Complexes in the Galilee with typological features similar to those in Judea have been surveyed, mainly by M. Aviam and Y. Shahar, although none have been found at any of the specific sites mentioned by Josephus. The few published archaeological finds from caves in the Galilee are not unequivocally dated to the Second Jewish Revolt. Indeed, no Bar-Kokhba coins have been found to date in the Galilee, and historical sources do not support the possibility that the Galilee took part in the revolt. Y. Shahar has recently pointed out that the archaeological findings from the Galilean systems can be dated to the Roman period, mainly to the second half of the first and the first half of the second centuries CE. He emphasizes that this dating cannot solve the question of whether the complexes were dug for the First or in preparation for the Second Jewish Revolts. We cannot exclude the latter possibility, even if the inhabitants of the Galilee ultimately did not participate in that revolt.

The phenomenon of the hiding complexes seems to have reached its peak of sophistication and geographical distribution between the two revolts. The largest complex at

DISTRIBUTION

The vast majority of the hiding complexes are located in the Judean Shephelah. Most are concentrated within the area bordered by

The absence of hiding complexes in central Benjamin (west of Ramallah and north of the Jerusalem–Emmaus line) may be due to its geology, namely that it contains strata of hard limestone that are difficult to cut through. However, surveys in the region have generally focused on major archaeological sites and not the inspection of every fissure and crevice, perhaps explaining the absence of data on hiding complexes in the area.

The distribution of hiding complexes coincides with that of Jewish settlements in Judea, as well as of coins from the Second Jewish Revolt. The main bloc of Jewish settlements in Judea seems to have extended from the area of Antipatris (Aphek in Sharon) in the northwest, eastward along

AMOS KLONER, BOAZ ZISSU

INTRODUCTION

One of the fascinating aspects of the Second Jewish (or Bar-Kokhba) Revolt against Rome is the extensive use of underground cavities and installations for hiding, escape, refuge, defense, and guerilla warfare. Two main types of caves can be distinguished—refuge caves and hiding complexes. The refuge caves are natural subterranean spaces found mainly in the Judean Desert, in the eastern slopes and cliffs of Judea overlooking the Dead Sea and the Jordan Valley (see Vol. 3, pp. 816–837). The artifacts found in them make it evident that they served as places of refuge for the inhabitants of the Judean Mountains and the Jordan Valley when they fled for their lives at the end of the Second Jewish Revolt. The archaeology of the caves has been studied and summarized by H. Eshel and D. Amit.

The hiding complexes, on the other hand, were artificial subterranean spaces, quarried under or near residential buildings in ancient settlements. They are found mainly in the Judean Shephelah, but also in the Hebron and Beth El Hills. They were usually cut out of the soft limestone, which is common in the Shephelah, but also out of the harder formations of limestone found in the mountainous regions. The majority of the complexes were completed prior to or during the Second Jewish Revolt. Recently, the dating of a few networks—mainly small, unsophisticated ones—has been moved up to the time preceding the First Jewish Revolt.