Kafr Samir

IDENTIFICATION

The site of Kafr Samir is located to the south of the city of Haifa, about 1.5 km from the Mediterranean coast and at the foot of Mount Carmel. It covers an area of approximately 62 a. Kafr Samir had previously been identified with Castra of the Samaritans (Castra Samaritanorum) of the Byzantine period, mentioned by Antoninus of Piacenza (Itinerarium—c. 520

EXCAVATIONS

Kafr Samir was first noted by C. R. Conder in 1876, and surveyed by Y. Olami in 1965. A number of probes have been conducted in recent years, mainly by A. Siegelmann (1988) and S. Yankelevitch (1990). Extensive salvage excavations (over an area of c. 8 a.) were directed by Z. Yeivin and G. Finkielsztejn on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1993–1997, prior to construction of a tunnel through Mount Carmel. More limited explorations were subsequently undertaken by E. van den Brink in 1998 and Z. Yeivin in 1999. G. Finkielsztejn, with the assistance of H. Barbé, directed an additional extensive excavation to the southeast in 2000–2001, covering 0.6 a. The northern half of the excavated area was reburied, while all the other remains were dismantled down to bedrock.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE CHALCOLITHIC PERIOD. Two phases of the early Chalcolithic period were discerned in a natural cave situated below the buildings of the Byzantine city, to the south of the center of the settlement. The earlier phase included pits lined with slabs, probably of domestic use. In the Late Chalcolitic period, the cave was used for the burial of about 26 individuals in at least 8 ossuaries. The ossuary typology suggests a connection with the Peqi‘in culture of Upper Galilee.

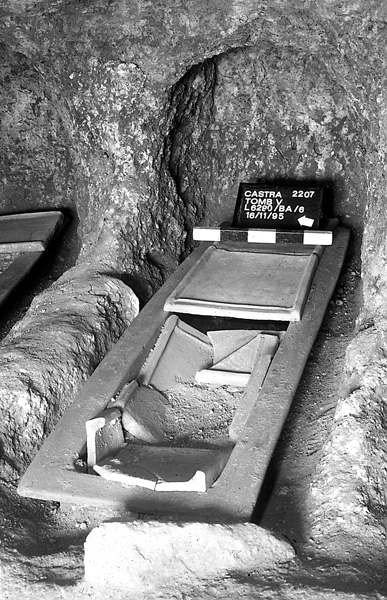

THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE. Four burial caves, one of which was fully preserved with a shaft and two chambers intact, were dated to the Middle Bronze Age I and II. Much of the material in these caves was recovered intact, despite disturbances from the overlying Byzantine occupation. In addition, several individual elongated rectangular tombs carved in the bedrock with a channel at the bottom (creating a transversal section in the form of a funnel) were detected by ground penetrating radar (GPS) after the discovery of two such examples during the excavation. The skeletons laid in the channels of these two tombs were not accompanied by grave goods. A tentative date in the Middle Bronze Age I is suggested by finds from this period recovered from the immediate vicinity.

THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD. To the east of the site, a winepress was abandoned in the late second–early first centuries BCE. At the bottom of the installation was a grinding stone, and retrieved from the fill were fragments of stamped Rhodian amphora handles and contemporary Phoenician jars. The vat and treading floor were carved in the bedrock and coated in simple plaster. In a nearby cave with a shaft, a burial of an adult accompanied by a child burial in a Koan amphora and a contemporary unguentarium were found. Another plastered winepress situated in the center of the site contained a fill of Byzantine material but may also be dated by comparison to the Hellenistic period.

THE ROMAN PERIOD. The first century CE is represented by a small quantity of pottery and some ten tombs. Remains of the settlement from the second and third centuries CE comprise debris in a quarry and under a few floors, as well as large amounts of pottery dumped in a cave. A lamp dating to the end of the third century CE was found in a mikveh sealed below a Byzantine house, evidence for a relatively limited, rural Jewish settlement at the site. A unique clay (bread?) stamp bearing the word “shvi‘it” was found in later debris and cannot be precisely dated. Its exact purpose is also unknown, although it definitely refers to the sabbatical (“seventh”) year. The primary remains of the second and third centuries CE are some 20 tombs with loculi (kokhim) in the necropolis situated downhill to the west of the Byzantine settlement. Most of the tombs (c. 50 in number) contained clay sarcophagi covered with roof tiles and a wealth of finds: glass vessels, bone pins and pendants, gold rings, and clay lamps. This is the southernmost limit of the distribution area of sarcophagi imported from Cyprus, the center of which was Acco, probably the port of entry of these items. Terracotta figurines of deities, stone incense burners in the shape of altars, and clay masks of Dionysos and Ariadne are evidence of a pagan population, perhaps Hellenized Phoenicians. One lamp may bear a Samaritan inscription in Greek: “Eulogia Oips(istos).” The size and importance of the necropolis would seem to indicate that it served a large area stretching to the south of the Carmel from as early as the Roman period. A hoard of 19 Antoniani coins dated to the third quarter of the third century CE was found in one tomb. Of 794 legible coins found at the site, only 54 date prior to the Byzantine period. Most of the tombs of the Roman period were no longer in use in the Byzantine period.

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. The city was occupied continuously from the beginning of the Byzantine period to the eighth century CE. Due to erosion and later stone robbery, the vast majority of the buildings were preserved to a height of only one course, rarely more, founded directly on the bedrock. However, in the area excavated in 2000–2001 in the southeast of the site, located on the slope of Mount Carmel, the ground-floor walls were preserved up to 2.5–3.0 m. Most of the entrances were blocked and the rooms appeared to have been intentionally filled. This fact, together with clear signs of collapse and rebuilding of some walls, is evidence of an earthquake that occurred in the middle of the sixth century CE. The significant building remains provide the plan of most of the settlement and attest to a bustling small city, whose economic life was based on the industrial production of wine and oil, pilgrimage, and trade.

City Planning. Adapting to the sloping bedrock, the buildings were oriented roughly north–south and east–west. The two longer, wider streets uncovered were oriented east–west and linked the residential area occupying the eastern two-thirds of the city with the mainly industrial zone and the necropolis in the western third. The north–south streets were little more than lanes leading to houses. Only one of these streets, in the easternmost area, was longer, giving access to several houses on either side of it. The walls of the buildings were generally strong, having been constructed using a combination of techniques. Dwelling units, grouped in irregular insulae, were roughly rectangular, with rooms surrounding a paved courtyard. There were beaten-earth, stone-paved, and sometimes tessellated floors. Wine or olive-oil presses were incorporated into the urban network. To the north, a complex of at least two “villas” was connected to the northeastern church (see below).

Water Supply. A spring was located to the east of the city, and a vast c. 550-cu-m reservoir was hewn in the bedrock next to it. Another reservoir was partly uncovered to the north. In addition, several deep bell-shaped cisterns were scattered throughout the city. They exploited the sloping topography and the proximity of the outlet of a wadi to the east.

Churches. Two basilical churches were exposed in the excavations. The larger and earlier of the two was situated in the northeast of the settlement. The remains of its mosaic pavements have enabled reconstruction of the building phases of the church. These phases serve as the backbone for those of the entire city. The earliest phase may be dated to the end of the fourth or beginning of the fifth centuries CE, when the church was a rather modest building (16 by 16 m) with a nave and two aisles separated by columns, a narthex, probably a bema, but no evidence of an apse to the east. There were two chapels to the north. All of the floors were paved with white mosaics adorned with simple panels of blue geometric designs. The nave panel contained a centered polychrome rainbow pattern. This early phase seems to correspond with the founding of the settlement (between 333 and 451 CE, according to historical sources).

In about the middle of the fifth century, the entire complex was extended to the east (23 by 16 m), where an apse—probably comprising semicircular steps of a synthronon, with a throne or cathedra in its center—is clearly evident. Colorful mosaics were now laid in the aisles but probably not in the nave. A baptistery was built in the form of a Greek cross, contiguous to the southern pastophorium, outside the main hall. The volume of the immersion vat was eventually reduced when three of the branches of the cross were filled with ashlars. A stone-paved atrium (c. 16 by 16 m) was probably built in this phase, covering earlier buildings. This is the only area where two building levels could be discerned. Five of probably seven original steps of a monumental staircase were uncovered to the west of the atrium.

Following fire damage, evidenced by burnt mosaics, the surface of the entire building was covered in a thick plaster layer and paved with new mosaics, probably in the last quarter of the sixth century. The baptistery was overlaid by a large chapel paved with a mosaic containing a bilingual inscription in Greek and Syriac. A new chapel with a reliquary set below a low marble table was added to the south. Sometime in the seventh century another chapel was added to the southwest of the main hall. It was paved in a mosaic with two medallions: one in the center, with an inverted alpha-omega, the other near the entrance, depicting three pairs of sandals and a small cross. Finally, at the end of the seventh century, a small chapel of poor quality was added on the southern end of the narthex. The remains of a later floor made of broken marble slabs laid above the northwestern end of the church attest to a poor post-Byzantine occupation.

The western church (16 by 12 m), a basilica without a narthex, was built sometime in the second half of the fifth century, as evidenced by the style of its mosaics and similarities to those of the second phase of the main church. The construction of a second church would seem to indicate a period of prosperity, perhaps after the city became the see of a bishop. A single construction phase was discerned in the church. The southwestern corner was built over a large reservoir, covered with mosaics, and roofed, as attested by the bases of crossed arches. The mosaics were poorly preserved, except for those in the southern aisle and the apse. The pavement of the latter displays a large Latin cross emerging from an amphora. A chapel with a reliquary was added along the southern side of the church, probably at the end of the sixth century CE.

“Villas.” Two large buildings were situated to the west of the northeastern church, on either side of a wide street leading to the stairs of the church atrium. Most of the rooms, including at least one triclinium, were paved with mosaics or stones of simple workmanship. The central panels of a number of the mosaics contain medallions with a cross or an inscription. A bath was constructed in the corner of one of the villas. To the south, stone fences attest to gardens or orchards. The view from the villas was open to the west, in the direction of the sea, recalling the villa maritima of the Roman period in Italy and elsewhere. This complex of villas may have been the residency of the bishop.

Presses. Ten winepresses with at least 16 vats and 9 olive-oil presses with 23 pressing units provide evidence for industrial production far beyond the needs of the town’s inhabitants. Construction phases in which facilities were enlarged or improved attest to increases in production and evolution of techniques. Winepresses were covered with white mosaics, sometimes decorated. One of them bore a dedicatory inscription and another had depictions of crosses, a chi-rho, and an alpha-omega. Steps were built in the vats. Experimental wine production was conducted in one of these presses by Y. Dray, demonstrating the function of the treading floors of the surrounding “secondary” units. The central and main surface was used for the circulation of people, the flow of the must, and secondary pressing. Tombs with loculi were hewn into the walls of two winepress and their vats were turned into dromoi.

In the olive-oil presses, the lever and two-weight system was by far the most common. Direct pressing of olive oil was quite rare. In one press, there was evidence for the upgrading to the lever and screw technique. The bottom of the cylindrical vats was paved in white mosaic.

The Necropolis. The necropolis is concentrated downslope to the west and southwest of the city. Over 50 tombs were excavated, the vast majority in use during the Roman and Byzantine periods. Some of the tombs contain individual burials in a single loculus (kokh), but most are family tombs comprising a stepped dromos, an entrance often blocked with a rolling stone, and one main chamber with loculi. Due to the soft, crumbly nature of the bedrock, most of the chambers were plastered, and the loculi were often built in a trough-like shape, sometimes with arcosolia. In one instance the remains of several hundred individuals were packed in one large stone sarcophagus, perhaps after some cataclysmic event, such as the earthquake that caused the collapse of some of the buildings mentioned above. Accompanying the burials were oil lamps, glass vessels, bronze and iron rings (some inscribed), and a few buckles. Bronze and bone cosmetic utensils, as well as dice and amulets, were also common, in accordance with burial practices in the Levant.

The Finds. A vast ceramic corpus was recovered, including Late Roman red slip vessels of various origins, jars of Levantine origin, and amphorae from most of the Mediterranean regions as well as the Black Sea coast, attesting to extensive trade contacts. Apart from the oil lamps, the pottery vessels were poorly preserved. Crosses are found on every category of finds, indicating the strong Christian affinities of the population of the site. Hundreds of glass vessels, mostly dating to the Middle Roman and Byzantine periods, were deposited in the tombs, providing evidence of prolific local production, specifically an active workshop in the vicinity of the site, as yet undiscovered. Of 731 legible coins of the fourth to eighth centuries CE (from both the settlement and the tombs), 81 percent are attributed to the fourth–sixth centuries (with over half minted in the fourth century), the remaining dated to the seventh–eighth centuries CE. The numismatic, ceramic, and glass finds confirm that the site was a major administrative center hastily abandoned after the Arab conquest.

THE ISLAMIC AND MAMELUKE PERIODS. Several “Byzanto-Arab” coins found in the fill of a winepress vat, as well as an intact, seventh-century CE glass vessel lying in an oil-press pit, are evidence for the abandonment of the site early in the Islamic period. A small amount of pottery and coins attest to a very limited occupation in the Islamic and Mameluke periods.

Pottery Kiln. To the west of the western church, a round pottery kiln (diameter c. 2.5 m) with a pillar in its center was exposed. A curving wall delimited a working area where ashes and fragments of roof tiles were found, although the relation between the working area and the kiln could not be ascertained. The kiln is of a later date than the church, and was perhaps in use during the late Byzantine or Early Islamic period.

Lime Kiln. In the southwestern necropolis, a rectangular, two-room structure (17 by 8 m) was built over a fill covering graves of the Roman and Byzantine periods. A conical lime kiln was installed in the northern room, which was connected to the southern room by a triangular opening in the wall. The latter, probably the working area, was accessed by a descending staircase. This well-preserved complex should be dated at the earliest to the Early Islamic period.

ZEEV YEIVIN, GERALD FINKIELSZTEJN

IDENTIFICATION

The site of Kafr Samir is located to the south of the city of Haifa, about 1.5 km from the Mediterranean coast and at the foot of Mount Carmel. It covers an area of approximately 62 a. Kafr Samir had previously been identified with Castra of the Samaritans (Castra Samaritanorum) of the Byzantine period, mentioned by Antoninus of Piacenza (Itinerarium—c. 520