Karkom, Mount

INTRODUCTION

The site of Mount Karkom was excavated by E. Anati during the 1990s. Its archaeological remains include Bronze Age altars and shrines on the mountain plateau and stone-built foundations of Bronze Age habitation sites at its foot. The site appears to have served as a cult place in the late fourth and third millennia BCE, and perhaps as early as the Paleolithic period. The cultic role of the mountain appears to have ceased during the second millennium BCE, a consequence of drought.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

SITE REMAINS. During the 1990 season, an early Upper Paleolithic site (HK 86B) was uncovered on Mount Karkom, including an area where several large flint boulders had been erected. Early man selected and brought to this spot 42 natural stones with vaguely anthropomorphic shapes. Only a few of these showed signs of having been worked by human hands. If indeed this impressive site had a social and cultic function, it may be the earliest shrine known in the Near East, probably over 30,000 years old. The lithic industry at this site, like that of seven other sites on the plateau, is characterized by an early blade industry with a strong persistence of Levallois flaking technique. It has been defined as belonging to the Karkomian industry, which is regarded as an initial phase of the Upper Paleolithic. Later Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic phases have thus far appeared only sporadically.

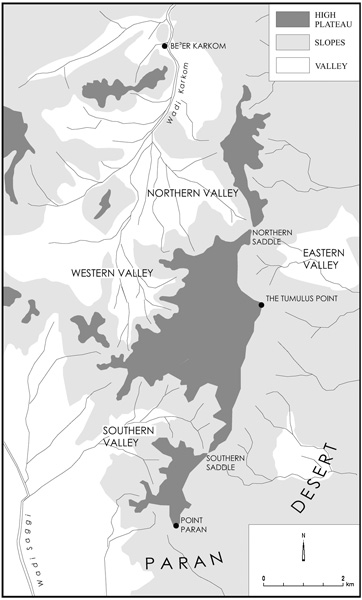

The next most prevalent period represented has been defined as the BAC, or Bronze Age Complex period; it includes the Chalcolithic period, the Early Bronze Age, and the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. Hamlets and remains of habitation and camp sites of the BAC period are located in the valleys surrounding the mountain, while the mountain plateau in that period appears to have been reserved for cultic structures. In the center of the plateau is a BAC structure with a platform or altar facing east, probably a small temple.

Several of the habitation sites include courtyard buildings, a typical site consisting of a large enclosure surrounded by smaller rooms. Another common type of site is called a “plaza site,” with stone foundations of huts built in a circle around a central plaza. Also recorded were a few hamlet sites, which are clusters of buildings surrounded by threshing floors; row-sites, so called because they consist of stone basements of small huts in a row; and campsites, likely to have served nomadic groups. The variable types of habitation sites present in the BAC period indicate that different ethnic groups were present in the area. Some of the sites were suitable for large family groups or clans with spacious living quarters; others are private habitations for groups of nuclear families.

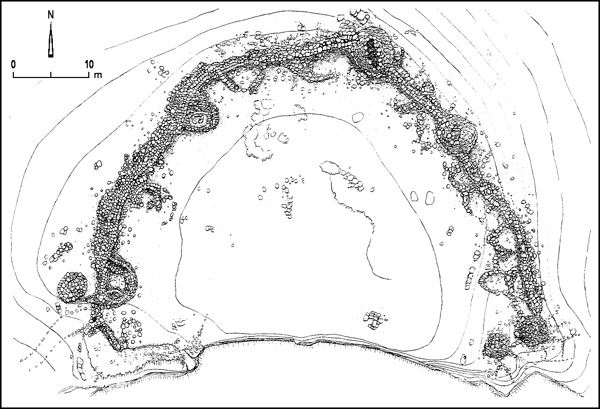

The presence on Mount Karkom of small shrines defined as “private shrines” and of “testimony tumuli” is a peculiar characteristic of the site. The private shrines, at least 18 in number, consist of one or more standing stones naturally anthropomorphic in shape—so-called “idols” or ceremonial pillars—encircled by smaller stones. Occasionally the standing stones were worked by human hands, with eyes or a mouth added. The testimony tumuli are heaps of stones which cover an altar or a standing stone. In a few cases, excavations revealed the presence of ash around such stones, below the heap. In one case, a heavy rectangular black stone was found to have been positioned on the base rock together with other smaller stones, forming a sort of platform. On top of it was a white stone intentionally cut in the shape of a half circle or half moon (length 60 cm, weight 44 kg). A flint tool, possibly used to cut this stone, was found near it. At the foot of the platform, the presence of ash and blackened stones indicates a conflagration there. The platform with the white moon on top was covered by a stone heap over 7 m in diameter and 2 m high. This testimony tumulus seems to have been built to commemorate or dedicate the site to the moon or the moon god. In all, over 60 tumuli were recorded; several of these may have simply been burials, but others are likely testimony tumuli. The ubiquity of such monuments on the mountain plateau suggests that it was an enormous cult site. Found at the foot of one of its slopes was a structure with the foundation of a rectangular bamah, next to which were a dozen

The BAC material culture is widespread in the Sinai Peninsula, the Negev, and the Arabah. It reflects a Chalcolithic tradition, characterized by an abundance of fan scrapers, points, and borers. It had a long duration, lasting until the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. Pottery is rare and mostly undecorated. Middle Bronze Age I metallic ware appears at a few sites.

No Late Bronze Age site has yet been discovered in the survey. One Iron Age site, two Hellenistic sites, and more than 50 Nabatean, Roman, and Byzantine sites were recorded on and around the mountain. Most contained remains of stone-built hut foundations. The largest of these habitation sites belongs to the Hellenistic period and includes more than 100 building units. The Roman and Byzantine periods are characterized by the presence of terraced agricultural fields, stone-built animal enclosures, and other structures revealing a widespread agrarian use of the territory.

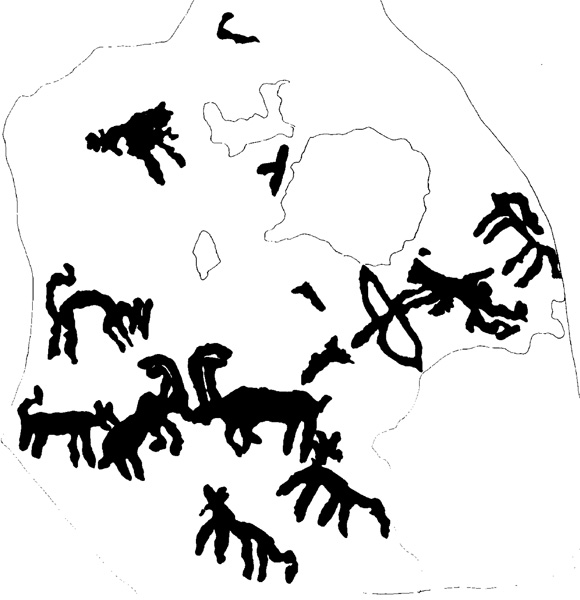

ROCK ENGRAVINGS. The mountain has a rich array of rock engravings, with thousands of engraved images in more than 150 groups. The periods represented range from pre-Neolithic to Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic. Style I, known from the site of Kilwa in Arabia, has large typically Upper Paleolithic animal figures. Style II, identified in earlier research in the Negev and Sinai Peninsula, is ascribed to the Neolithic period; it is characterized by elegantly stylized figures of wild animals, primarily antelopes. Style III displays scenes of antelope hunting. Hunters wear skins and use bows, and are accompanied by domesticated dogs. The style attests to the way of life of late hunters and is probably contemporary with the Chalcolithic period and part of the Early Bronze Age style IVA, in which domesticated animals are widespread for the first time. Style IVA is also the only style in which domesticated oxen are present, perhaps an indication of better climatic conditions during this period. Style IVB is unknown at the site but is common in the central Negev and well known from the “Chariot Cave” of Timna‘ in the Arabah Valley.

There seems to be a gap in rock art production during the second millennium BCE. Style IVC starts in the Iron Age and develops into the Hellenistic and Roman periods. It depicts individuals engaged in hunting, livestock rearing, and caravan trade, and is the first to depict domestic camels and horses. Pictures of the later phases of this style are accompanied by inscriptions in various Semitic scripts. The inscriptions probably do not mark the arrival of a new people, but indicate the spread of literacy among local tribes. Styles V and VI belong to the Roman–Byzantine and the beginning of the Early Islamic periods. Most of the Nabatean and Thamudic inscriptions are associated with images of this style. In the course of the periods corresponding to styles V and VI, a gradual schematization of the figures occurred, culminating in the wassum and tribal marks of style VII, which dates to the past few centuries.

GEOGLYPHS. Pebble drawings or geoglyphs have been discovered on the mountain and in the surrounding valleys. These are large figures portrayed by arranging stones on the ground or clearing them from parts of the ground surface to create a negative image. A few of these can be identified as representing animals, some over 40 m long; others are of animal and human figures together, or of geometric patterns. Such geoglyphs are more clearly visible from the air than the ground. They are considered to be symbolic offerings to a sky god. Some are associated with flint implements belonging to the Chalcolithic period and the Early Bronze Age. It is doubtful, however, that all of the geoglyphs belong to the same period. As a working hypothesis, they are attributed to an era ranging from the Neolithic period to the Early Bronze Age.

SUMMARY

The Upper Paleolithic sanctuary (HK 86B) at Mount Karkom indicates that the mountain was a place of worship from very ancient times. A few campsites and rock engravings from the Neolithic period have been found on the mountain. In the BAC period, the mountain was used as a ceremonial and cultic high place. Numerous rock engravings of religious significance were carved; and

EMMANUEL ANATI

INTRODUCTION

The site of Mount Karkom was excavated by E. Anati during the 1990s. Its archaeological remains include Bronze Age altars and shrines on the mountain plateau and stone-built foundations of Bronze Age habitation sites at its foot. The site appears to have served as a cult place in the late fourth and third millennia BCE, and perhaps as early as the Paleolithic period. The cultic role of the mountain appears to have ceased during the second millennium BCE, a consequence of drought.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

SITE REMAINS. During the 1990 season, an early Upper Paleolithic site (HK 86B) was uncovered on Mount Karkom, including an area where several large flint boulders had been erected. Early man selected and brought to this spot 42 natural stones with vaguely anthropomorphic shapes. Only a few of these showed signs of having been worked by human hands. If indeed this impressive site had a social and cultic function, it may be the earliest shrine known in the Near East, probably over 30,000 years old. The lithic industry at this site, like that of seven other sites on the plateau, is characterized by an early blade industry with a strong persistence of Levallois flaking technique. It has been defined as belonging to the Karkomian industry, which is regarded as an initial phase of the Upper Paleolithic. Later Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic phases have thus far appeared only sporadically.