Kebara Cave

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

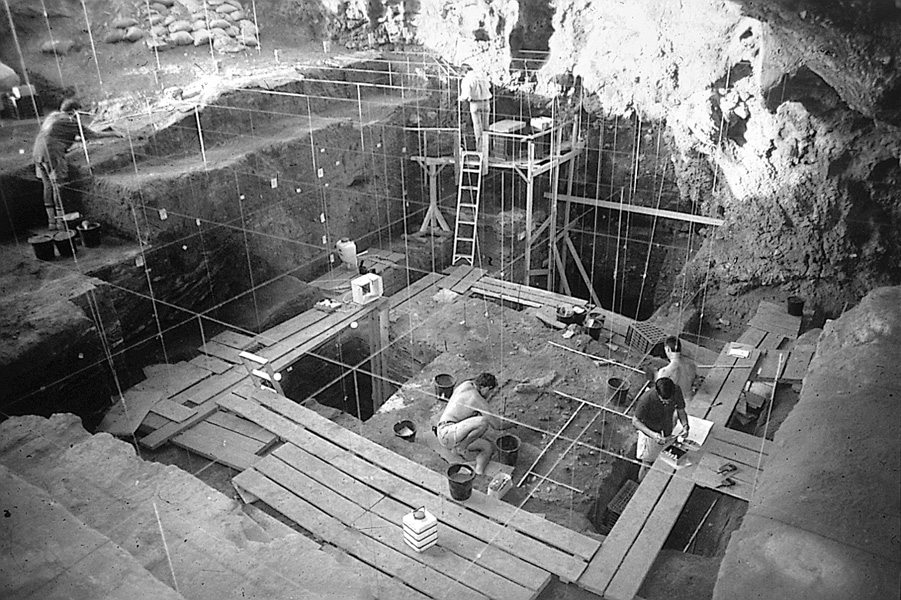

The new excavations at Kebara Cave (1982–1990) were aimed at establishing the chronological boundary between the deposits of the Middle and the Upper Paleolithic, as well as dating the Middle Paleolithic sequence. The excavations were conducted by O. Bar-Yosef on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and B. Vandermeersch of the University of Bordeaux I. The observable stratigraphy and the nature of the sediments as seen through micromorphology were the means for achieving the first aim. Thermoluminescence (TL) and electron spin resonance (ESR) were the radiometric techniques employed in dating the Mousterian deposits, while the Upper Paleolithic layers were dated by radiocarbon. The discovery of a Neanderthal burial during the second season (1983) and its preliminary publication motivated further dating. The obtained results indicated that the Middle Paleolithic sequence lasted from 64,000/59,000±3,500 to 48,300±3,500 years, while the Upper Paleolithic layers (as the younger ones were removed by F. Turville-Petre) date from 43,000/42,000–28,000

EXCAVATION RESULTS

The lowest deposits in the cave, namely units XVI through XIV, are predominantly natural accumulations, with virtually no anthropogenic contributions. Most of the overlying ashy sediments from units XIII through V result from the presence and activity of humans—the making and use of stone tools and hearths, the transport of fire wood, the utilization of plants for bedding and food, and the dumping of daily garbage. There is some evidence for infrequent denning by hyenas.

The new series of excavations confirmed the observation that, at the end of the Middle Paleolithic and during the early millennia of the Upper Paleolithic period, the cliff above the cave partially collapsed and large limestone blocks fell along the drip line. A few rolled into the chamber. In addition, all the sediments in the cave were tilted toward the unexposed sinkhole in the back of the cave. The process of tilting, which started toward the end of the Middle Paleolithic period (units VI–V), removed some of the older sediments and redeposited them by runoff from the cave entrance towards the rear wall. In this way, terra rossa silty clay from the exterior of the cave was washed in.

In the course of exposing the central area inside the cave, by continuing from the level left by M. Stekelis, it was found that what he considered to have been “hearths” were effectively concentrations of animal bones. But the major dumping zone of ash and the numerous flint artifacts and animal bones were along the northern cave wall. In the central zone, the distribution of bones was identified in three distinct areas continuing to a depth of at least 50 cm. This raised the question of whether the distribution of the bones reflects hominid activity or was simply the result of preservation conditions. The mineralogical analyses demonstrated that only the southernmost concentration was affected by dissolution, although these bone concentrations may originally have been the result of human activities. The almost complete skeleton of KHN 2, identified as a burial of an adult Neanderthal, was found at the edge of the well-preserved deposits. Only its left elbow region and the left femur showed signs of dissolution.

The work at Kebara proved that understanding the effects of diagenesis also has implications for the dating techniques of TL and ESR. Both are dependent in part on knowing the input of radiation from the sediments in which the flint artifact or tooth was buried. The radiation is derived mainly from small amounts of uranium and a radioactive isotope of potassium. The constant changes in the mineral assemblages alter the amounts of radiation affecting the dated item, making it almost impossible to obtain a reliable measurement. The published dates for Kebara took all these concerns into account.

The detailed study of the hearth structures, both in the field and through thin sections, provided information concerning the repeated episodes of burning, clearly indicating the use of the same installation during successive occupations. The micromorphological analysis identified different related features, such as in-situ hearths exclusively of white ash, hearth rake-out, and ashy accumulations. The evidence for cleaning surfaces is supported by the striking accumulation of burned bones away from the hearths. Similarly, a thick lenticular accumulation of white ash, the result of constant sweeping, was identified in the northeastern corner of the cave. The conclusion that the Middle Paleolithic inhabitants of Kebara systematically cleared quantities of garbage from their central space is unavoidable. The hearths were used by the Mousterian inhabitants of the cave for heat, light, parching plant food, and possibly roasting meat.

The abundance of successive occupations at the site, evidenced in the relatively rapid build-up of overlapping hearths and associated refuse, makes it difficult to trace spatial activities away from a particular fireplace. The rapid accumulation indicates that over 1,000 lithic pieces (larger than 2 cm) were produced over about 3,000 years, which reflects an intensive use of the cave. This observation corroborates the paucity of microfauna, which generally results from the accumulation of barn owl pellets.

FLORAL ASSEMBLAGES. The phytolith (silica elements) analyses support the conclusion that wood ash is a major component of the sediments in the cave. Wood was the main fuel used for fires, although the phytolith compositions vary significantly in the different layers. Wood charcoal indicates that Tabor and common oak were most frequently employed for making fires.

The large collection of charred seeds retrieved through the use of floatation techniques represents human choices of mainly legumes, gathered in the vicinity of the cave during springtime, the season when gazelle and fallow deer, the common hunted species, were fat depleted. During the fall, humans collected acorns and pistachio nuts and hunted.

FAUNAL ASSEMBLAGES. The analysis of the large, well-preserved collection of animal bones is still underway, but the first comprehensive report showed that Neanderthals and the Upper Paleolithic humans hunted fallow deer, gazelle, wild boar, and aurochs, and collected tortoise. The hunters targeted adult males or females depending on which sex was in better physiological condition, as indicated by the seasonal evidence derived from the cementum analysis. The carcasses were dismembered and transported or discarded, based on their bulk and food utility. The archaeological investigation recorded a change over time, from episodic late spring and summer occupations early in units XII–XIII, to intensive use as a basecamp in winter and early spring during the middle part of the Middle Paleolithic (units XI to IX), when hunting became a prominent activity. In the uppermost Mousterian units, the inhabitants shifted back to episodic, spring/summer camping in the cave, and hunting played a reduced role. Hence, the main midden near the northern wall accumulated during the time of units XI–IX.

LITHIC INDUSTRIES. The lithic analysis of a large collection from every unit demonstrated that the latest industry is what is often called the Tabun B-type. It is characterized by blanks removed mainly from unipolar convergent Levallois cores. Typical products are broad-based Levallois points, commonly with the typical chapeau de gendarme striking platform, and often having the special Concorde tilted profile when viewed from the side. Blades do occur in this industry, and sometimes form up to 25 percent of the blanks. This type of lithic industry is currently known from Tabun, Kebara, Sefunim, ‘Amud,

The Upper Paleolithic lithic assemblages retrieved from the southern section are of two types. The early one from units IV–III falls under the general category of blade industry and would fit the description of what Turville-Petre designated as layer E. It contains a blade/bladelet industry with retouched blades and end scrapers. This type of assemblage was originally called “Early Antelian” by Garrod and may now be tentatively attributed to the Early Ahmarian. Units II–I contain an Aurignacian assemblage dominated by end scrapers on Aurignacian blades, carinated and nosed scrapers, and Aurignacian blades; and marked by a proliferation of bladelets. One split-base point was found in this context, supporting the notion that the Levantine Aurignacian is related to the same culture across Europe.

OFER BAR-YOSEF

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

The new excavations at Kebara Cave (1982–1990) were aimed at establishing the chronological boundary between the deposits of the Middle and the Upper Paleolithic, as well as dating the Middle Paleolithic sequence. The excavations were conducted by O. Bar-Yosef on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and B. Vandermeersch of the University of Bordeaux I. The observable stratigraphy and the nature of the sediments as seen through micromorphology were the means for achieving the first aim. Thermoluminescence (TL) and electron spin resonance (ESR) were the radiometric techniques employed in dating the Mousterian deposits, while the Upper Paleolithic layers were dated by radiocarbon. The discovery of a Neanderthal burial during the second season (1983) and its preliminary publication motivated further dating. The obtained results indicated that the Middle Paleolithic sequence lasted from 64,000/59,000±3,500 to 48,300±3,500 years, while the Upper Paleolithic layers (as the younger ones were removed by F. Turville-Petre) date from 43,000/42,000–28,000

EXCAVATION RESULTS

The lowest deposits in the cave, namely units XVI through XIV, are predominantly natural accumulations, with virtually no anthropogenic contributions. Most of the overlying ashy sediments from units XIII through V result from the presence and activity of humans—the making and use of stone tools and hearths, the transport of fire wood, the utilization of plants for bedding and food, and the dumping of daily garbage. There is some evidence for infrequent denning by hyenas.