Kedesh, Tel (in Upper Galilee)

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

From 1997 to 2000, two exploratory and two full seasons of excavation were conducted at Tel Kedesh by an archaeological expedition under the direction of S. Herbert of the University of Michigan and A. Berlin of the University of Minnesota. Aside from a step trench in the southern end of the northern mound, the excavations were confined to the southern lower mound. In the first exploratory season of excavations, two small trenches, dug just below surface level, uncovered substantial Hellenistic remains of a house dating to the middle of the second century BCE and a portion of a large enclosing wall on the edge of the lower mound. In the second exploratory season, of one week’s duration, a magnetometric survey was conducted that revealed the outlines of several large building complexes as well as a fairly regular north–south village grid plan. One particularly impressive structure appeared in the southeastern quadrant of the mound, adjacent to the house uncovered in the 1997 probe. This building, referred to as the Hellenistic Administrative Building on the basis of its date and function, was systematically explored during the 1999 and 2000 seasons.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

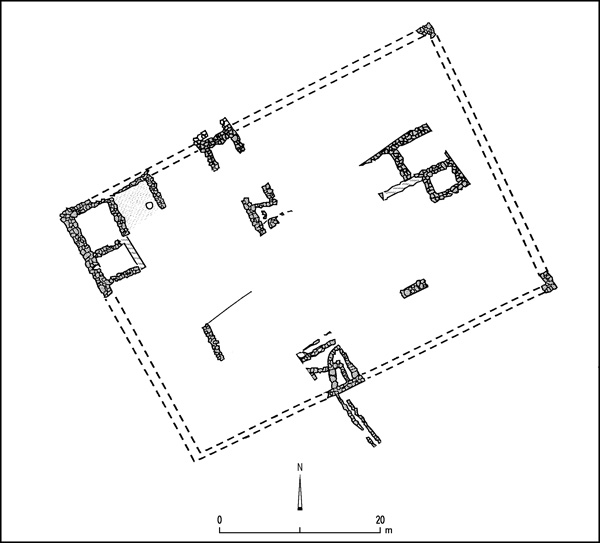

The Hellenistic Administrative Building was a large structure, 56 m (east–west) by 40 m (north–south), with an impressive entrance on the southern side leading to an off-center open courtyard (14 by 10 m). Single rows of rooms lying along the building’s northern and western sides were separated from the courtyard by a narrow corridor. The eastern half of the building contained a network of interconnecting rooms that probably served as the living quarters. A group of rooms in the northeastern corner of the courtyard appears to be a bathhouse similar to one found at nearby Tel Anafa. The rooms on the northern and western sides seem to have been administrative or ceremonial in nature. Both the size and the plan of this building are typical of official Persian and Hellenistic structures elsewhere in the Near East; it was clearly a public building. The finds in the building date, for the most part, to the first half of the second century BCE, making it contemporary with the house found in the 1997 probe. Nothing on or under the floors of the building dates to later than the middle of the second century BCE. There is also evidence of a Persian period predecessor.

The finds in the three rooms in the northwestern corner of the building enable the identification of some of its administrative functions and to some extent of the administrators themselves. In the room adjoining the corner, 14 enormous jars (2.6 m high) were found leaning against the walls. The analysis of the residue in two of the jars (carried out at the Pillsbury Research Labs in Minneapolis) revealed that their content was bread wheat. Two Rhodian wine amphorae were also found in the room. These vessels clearly show that the rooms served as storerooms for food and drink. The corner room west of the storeroom and the corridor to its south served as an archive, as can be inferred from the discovery of more than 2,000 thumbnail-sized clay sealings. These are tiny clay pellets (averaging 15 mm in length) that bore impressions of individuals’ seal rings and were commonly used to seal and notarize papyrus documents in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Early Roman periods. The sealings are all that remain of what must have been a sizeable archive. Most of the sealings bear images, 75 percent of them recognizable Greek gods and heroes, with the goddess Tyche being the most common. There are a considerable number of Seleucid imperial portraits, including several of the kings who ruled during the years that the building was in use (from the third to the mid-second century BCE). A small number of Phoenician seals were also found; some bear inscriptions that mention the city of Tyre, some are identical to images on Phoenician coins, and about 15 bear the image of the goddess Tanit alongside the inscription in Phoenician: “he who [rules] over the land.” This last group probably belongs to a local official, perhaps a Phoenician governor appointed by the Seleucid king to administer the combined territories of southern Phoenicia and northern Israel.

The datable evidence indicates an abrupt, though temporary, abandonment of the Hellenistic Administrative Building shortly after the middle of the second century BCE. This date is supported by the two Rhodian amphorae in the storeroom, one dating to 146 BCE and the other to 180–145 BCE. Dated sealings from the archive include three from 164–163 BCE and one from 148–147 BCE. The later dates are very close to the year of the battle between Jonathan and Demetrius in the plain of Hazor, reported in 1 Maccabees (11:63–74) and in Josephus (Antiq. XIII, 154–162). It seems likely that the Greek defeat in this battle and the subsequent retreat and loss of life in their camp near Kedesh was the reason for the building’s abrupt abandonment. Other evidence, however, suggests that the building’s abandonment was not permanent. In all the excavated areas, only the archive room was found to have been destroyed in a conflagration. In this fire, which destroyed the papyrus archive (and baked the clay sealings), only a few of the more than 50 pottery vessels found on the floor of the room were burned. The vessels had been covered with a thin layer of soil that apparently protected them from burning, suggesting that the room had been abandoned, perhaps for a period of several years, and only later set on fire. Thus, it appears that the building suffered at least two catastrophes during the third quarter of the second century BCE, the first being the hasty abandonment of the building itself and the house to its west, and the second being the deliberate setting on fire of the corner archive room.

These events were followed by a reoccupation, dated by coins, amphora handles, and pottery to the last third of the second century BCE. The new settlement appears to have been quite prosperous, with the inhabitants acquiring imported and regional luxury tableware (primarily Eastern sigillata A ware, as well as Cypriot and Egyptian vessels). The building clearly no longer functioned as an integrated administrative center and its use as a residence ended by the early first century BCE. Surprisingly, despite the Roman temple nearby, there is no evidence of occupation of the area in the Roman period.

In addition to the excavation of the above building, exploratory trenches were also opened in the center and highest point of the southern mound, where the southern end of an apsidal mortuary chapel of Byzantine date was uncovered. A white mosaic floor lay outside the chapel to the west. Stratigraphy was also examined between the modern village on the upper northern mound and the classical remains on the lower southern mound via a step trench on the southern slope of the upper mound, as well as by three soundings made in the saddle between the mounds. These examinations provided a sample of the occupation layers from medieval times through the Ottoman period but no continuum was found, the building remains dropping precipitously from the Abbasid period to the Middle Bronze Age. The northern mound was apparently unoccupied from the Classical period through Byzantine times. Judging from the fourth-century BCE Phoenician sarcophagi uncovered in the saddle, it may have been used as a necropolis during these periods.

ANDREA BERLIN, SHARON HERBERT

Color Plates

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

From 1997 to 2000, two exploratory and two full seasons of excavation were conducted at Tel Kedesh by an archaeological expedition under the direction of S. Herbert of the University of Michigan and A. Berlin of the University of Minnesota. Aside from a step trench in the southern end of the northern mound, the excavations were confined to the southern lower mound. In the first exploratory season of excavations, two small trenches, dug just below surface level, uncovered substantial Hellenistic remains of a house dating to the middle of the second century BCE and a portion of a large enclosing wall on the edge of the lower mound. In the second exploratory season, of one week’s duration, a magnetometric survey was conducted that revealed the outlines of several large building complexes as well as a fairly regular north–south village grid plan. One particularly impressive structure appeared in the southeastern quadrant of the mound, adjacent to the house uncovered in the 1997 probe. This building, referred to as the Hellenistic Administrative Building on the basis of its date and function, was systematically explored during the 1999 and 2000 seasons.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

The Hellenistic Administrative Building was a large structure, 56 m (east–west) by 40 m (north–south), with an impressive entrance on the southern side leading to an off-center open courtyard (14 by 10 m). Single rows of rooms lying along the building’s northern and western sides were separated from the courtyard by a narrow corridor. The eastern half of the building contained a network of interconnecting rooms that probably served as the living quarters. A group of rooms in the northeastern corner of the courtyard appears to be a bathhouse similar to one found at nearby Tel Anafa. The rooms on the northern and western sides seem to have been administrative or ceremonial in nature. Both the size and the plan of this building are typical of official Persian and Hellenistic structures elsewhere in the Near East; it was clearly a public building. The finds in the building date, for the most part, to the first half of the second century BCE, making it contemporary with the house found in the 1997 probe. Nothing on or under the floors of the building dates to later than the middle of the second century BCE. There is also evidence of a Persian period predecessor.