Kefar ha-Ḥoresh

INTRODUCTION

Kefar

The site was discovered following deep plowing for forestation. Excavations have been conducted since 1991 under the direction of A. N. Goring-Morris, initially on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority and subsequently of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

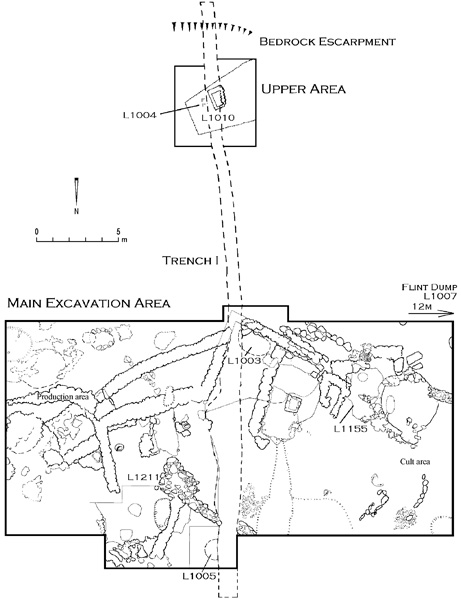

The excavated areas, totaling 425 sq m, include at least six distinct architectural levels that have been recognized through the 1.0–1.5-m-thick occupation. Radiocarbon dates and techno-typological characteristics of the lithic industry indicate that the site was occupied from the Early through the Late PPNB. Several low retaining and/or compound walls cross the site at right angles to the slope. Four main activity zones can be identified through most of the complex stratigraphy: (1) The central funerary area comprises numerous lime-plastered surfaces, low bounding and slope-breaking walls, cists, platforms, and associated features and installations, as well as human graves in three discrete clusters. (2) An adjacent cult area, on the western and northwestern side of the excavation, exhibits variously sized and shaped plastered surfaces and an array of installations and walls, including single or grouped monoliths and stelae. (3) The midden deposit extends mostly on the southern and western sides of the excavation area, spilling under, over, and around the previously mentioned areas; it is accompanied by hearths and roasting pits, with large quantities of fire-cracked stones (some perhaps representing potboilers), together with numerous animal bones and other refuse, perhaps resulting from feasting activities. (4) The production and maintenance area, on the eastern side of the site, includes kilns, hearths, platforms, items associated with the preparation and application of lime plaster in some quantity (axes, querns, and other groundstone tools, as well as hammerstones), and discrete knapping floors.

ARCHITECTURAL REMAINS. The numerous lime-plastered quadrilateral surfaces vary greatly in size. The plaster reaches thicknesses of 2–12 cm and was often laid in patches rather than as a single surface. Some surfaces are associated with stone-built “framing” walls, one to two courses high, mostly located on the upslope sides, or by low mud-brick or daub parapets. Many plastered surfaces overlie or are directly associated with graves and seem to represent funerary and cultic installations rather than habitations. There are also rectilinear cist, platform, and “wall” graves. No chronological patterning has been noted among the different grave types.

A few short “walls,” sometimes with a larger monolith or groups of orthostats, are found either as rounded blocks or slab stelae up to 1.2 m high. Some monoliths are integral to the funerary monuments, while others are located around the fringes of this area. The differential use of friable nari blocks, and harder, rounded limestone dolomite blocks and stones for construction and other purposes seems to be patterned. Post-sockets are present, sometimes molded within plastered surfaces or more commonly as separate stone-built sockets with circular slab bases. However, these do not appear to provide coherent patterns in terms of post supports for roofing; since some overlie graves, they could represent markers or totems. In other cases, small upright “tombstones” mark graves. Hearths and ovens of different shapes are either sunk within plastered surfaces or occur as more isolated features. They are either molded from plaster- or ceramic-type substances and are carefully slab-lined or more roughly lined with stones. The funerary and associated architectural features tend to display considerable spatial redundancy through the stratigraphic sequence. This indicates careful monitoring and planning of activities within the cemetery area.

GRAVES. Burials occur throughout the stratigraphic sequence. Over 60 individuals have been identified from the various grave contexts. One burial type comprises graves with an emphasis on postcranial remains. Most are located within shallow pits, sometimes under lime-plastered surfaces; they also occur under or within walls or cists, as well as in open areas. They include single and multiple burials, sometimes partially coeval and sometimes sequential, as well as combinations of the two; some graves have complex histories of reopening to add burials. While some burials are articulated, repeated reuse of graves and the insertion of later corpses can lead to disturbed primary contexts that superficially look similar to secondary burials. The fill within graves is sometimes ashy, while in others a patch of chalky, plaster-like material was sprinkled over the top of the grave, prior to more systematic plastering. In some graves the fill merely reflects the nature of the surrounding sediment.

Primary burials are supine, flexed, or tightly contracted, whether on the side or sitting, and some must have been bound or placed in sacks or mats. No obvious orientation of bodies has been noted. The nature of secondary burials is complex; within multiple graves seemingly random jumbles of bones, small discrete “packets,” and occasional articulated limb extremities were documented, as were more or less complete skeletons. Initially, several of the disarticulated remains were interpreted as secondary burials. In one large, kidney-shaped grave (L1003), two headless primary adult burials, one with a headless infant cradled in its arms and a few fetal bones in the pelvic region, lined the base of a grave. Above and around them numerous postcranial bones, some in partial articulation, and mandibles representing another 13 individuals were found in an oval arrangement around the periphery of the pit. While some may represent disturbed primary burials, others more plausibly represent genuine secondary burials.

Another multiple grave complex (L1155) under a plastered surface had a complicated history of use. Analysis revealed that most burials in this complex were primary or disturbed primary burials, and included adults and children; there were also some secondary burials, including a skull cache with one plastered skull. Most strikingly, mostly human long bones, some still partially articulated, had been arranged towards the top of the grave to form a 1.5-m-long “depiction” of what appears to be an animal in profile. The head, foreleg, back, and tail seem to be indicated, while the belly and hindleg apparently had been disturbed by a later primary interment. It seems that this is not simply a fortuitous arrangement of disturbed primary burials.

A different grave class comprises isolated skulls, of which more than a dozen have been recovered. While post-mortem skull removal is, indeed, widespread at Kefar

Detailed study of the human remains indicates an unusual demographic profile in comparison with contemporary sites. While individuals of all ages from newborns through old individuals of both sexes are present, there is a significant peak in young mature adult males. A few of the skulls indicate in vivo deformation.

Obvious grave goods are, numerically, not common; nevertheless they are clearly present and do demonstrate patterns. Grave goods are associated with all of the burial classes described above, including not only adults, but, perhaps most significantly, children as well. Two classes of grave goods can be defined: items actually placed within graves; and what appear to be offerings placed near graves. They include more standardized chipped stone types, such as projectile points, axes, burins, borers, and blades; as well as stone beads, minerals, seashells, mother-of-pearl pendants, a lightly incised basalt slab, and “burnishing” stones within graves. These items are commonly complete. Co-associations of less obvious offerings are also found in or in close proximity to grave contexts. These include minute discoidal or flat polished pebbles of a variety of raw materials, 1–2 cm in diameter and very rarely incised.

Of particular interest are the clear associations of animal themes in several graves. In one lime-plastered pit (L1004), under a complex lime-plastered surface, a modeled human skull was found together with a headless gazelle (Gazella gazella) carcass. Beneath another plastered surface, a headless, contracted adult burial capped a pit (L1005) containing 360 bones of aurochs (Bos primigenius), some in partial articulation, representing portions of at least one adult bull, six female cows, and one immature calf, but virtually no cranial elements. There are one and, more probably, two instances of articulated fox (Vulpes sp.) remains in children’s graves. Half fox mandibles (pars per toto) also occur directly within graves. Artiodactyl horn cores were placed adjacent to one of the skull caches. Many of the above may represent talismans, charms, and tokens, perhaps pertaining to social, ritual, or other affiliations.

There are also various caches or items within the general funerary area, where the direct association with specific graves is less obvious. Thus, two caches of naviform flint implements, one of 16 and the other of 30 items, have been recovered close to isolated skulls. Most implements are unmodified blades, some conjoinable, though they also include single examples of complete tools: a projectile point, a sickle blade, a burin, a borer, and a notch. Other, often smaller caches of distinctive flint tools, groundstone tools, or seashells have also been recovered in this part of the site. Chalk platter and bowl fragments (intentionally broken?) were found immediately adjacent to and above some graves.

OTHER FINDS. Other symbolic or ritual items within the site include a variety of so-called “gameboards”—stones or slabs of various sizes with a series of regularly spaced drilled holes, some linked by incised lines. There are also palm-sized, sub-rectangular limestone or basalt slabs with multiple parallel incisions. A schematic human figurine carved from chalk was recovered, as were several small clay animal figurines, and some pottery. A few phallic representations, either natural or carved, were also found.

The faunal assemblage is especially abundant in the midden area, and includes mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella); goat, probably wild bezoar goat (Capra aegagrus); fallow deer (Dama mesopotamica); wild boar (Sus scrofa); wild cattle (aurochs) (Bos primigenius); red fox (Vulpes vulpes); hare (Lepus capensis); rodents; birds; reptiles, including tortoise (Testudo graeca); and rare fish. The goat remains may indicate incipient domestication.

The chipped stone assemblage is mostly ad hoc in nature, with many amorphous flake cores for making becs, coarse awls, and other less formal tools. There is also a distinctive component of naviform blade production for more standardized forms—sickle blades, projectile points, burins and chanfreins, and perforators. One small refuse pit yielded 120,000 items of debitage and debris, all deriving from naviform production, but few cores and virtually no tools. Bifacials, including axes, picks, massive borers, and tabular knives, represent a separate chaîne opératoire. Much of the assemblage is made of local raw materials, though some of the more standardized tool forms are of exotic flint, and some were heat treated. There are also obsidian artifacts.

Groundstone tools of limestone and basalt were common, including querns, bowls, mortars, and platters, as well as mullers, pestles, shaft-straighteners, and whetstones. Many of the items in the groundstone assemblage are associated with lime-plaster production and on-site application, others with funerary contexts. A typical bone tool assemblage has also been recovered. Ornamental and other non-local items include marine mollusks, especially Mediterranean Glycymeris violacescens and Cardium shells, together with some Red Sea and freshwater species. Beads and crayon “stubs” are also found, made from a variety of raw materials including turquoise and malachite.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the specific setting and contextual evidence of the finds at Kefar

A. NIGEL GORING-MORRIS

INTRODUCTION

Kefar

The site was discovered following deep plowing for forestation. Excavations have been conducted since 1991 under the direction of A. N. Goring-Morris, initially on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority and subsequently of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.