Masada

EXCAVATIONS ON THE SUMMIT

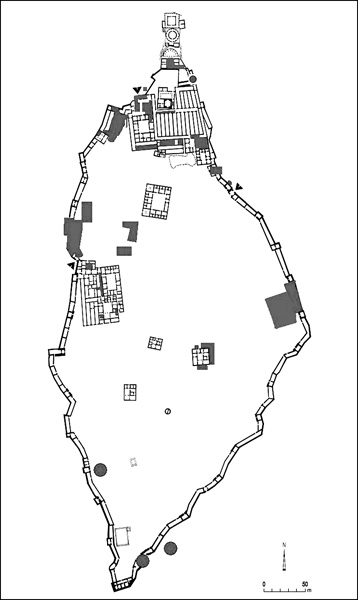

Supplementary excavations were conducted by E. Netzer and G. Stiebel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem upon the summit of Masada over several seasons spanning 1995–2000, as part of a development project undertaken by the Israel Ministry of Tourism and the Nature and Parks Authority. It followed a short season conducted by Netzer in 1989.

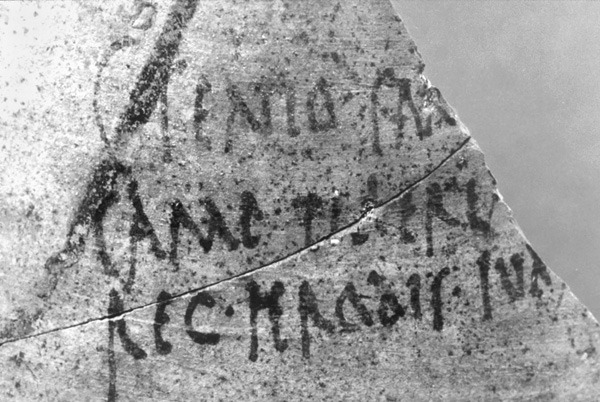

Main discoveries in the latest excavations at Masada are floors and assemblages datable to the Herodian period. The rich epigraphic finds include bilingual (Greek and Latin) inscriptions and ostraca from the time of the First Jewish Revolt. These may shed further light on the rebels’ communal life. New information has emerged concerning the entrances to the “acropolis” and on the area adjacent to the synagogue and cistern 1901.

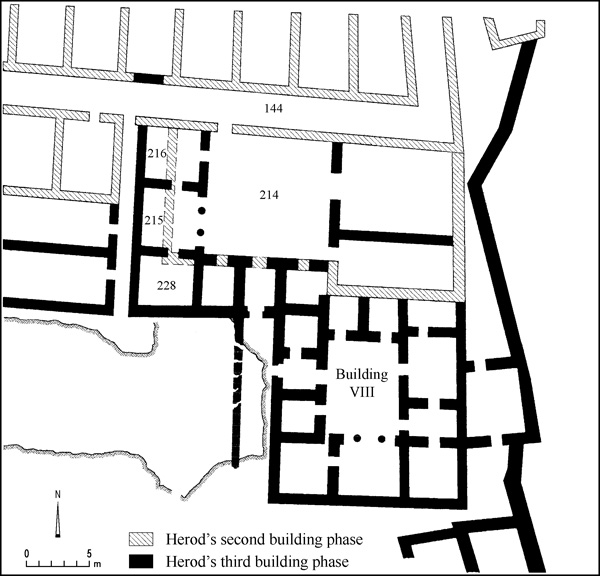

THE NORTHERN COMPLEX (“THE ACROPOLIS”). The excavation of the open area near the southeastern entrance to the northern complex, between building VIII (the commander’s house and his offices) and the main storeroom complex block (locus 214), was completed. It was found that this area had not yet been built during the second Herodian building phase, when the storeroom complex was constructed. During the third building phase, however, when building VIII was erected, a hall (10 by 8 m) was built on the area’s eastern side together with an elongated room, the function of which is unclear; apparently the hall was decorated with stucco. The hall would appear to have been used as the reception room by Masada’s commander; it stood perpendicular to the commander’s offices, rooms 228, 216, and 215, which were decorated with frescoes. The western part of locus 214 still served as the courtyard leading up to the northern complex through the corridors of the storeroom complex. A number of sections of corridor 144 and storehouse 121, which were not fully excavated in 1963–1965, were also exposed.

The renewed excavations included the complete exposure of square 174, at the northwestern entrance to the acropolis. During the third Herodian building phase this was a courtyard whose floor was entirely covered with plaster, partly hewn into bedrock, and partly laid upon a stone bedding. It is now clear that during the second building phase, when the courtyard was first built, there was a structure on its southeastern corner, adjacent to building VII. The use of this structure, which consisted of a room with a number of silos on the side, ceased during the third building phase, when the Water Gate was moved to this location and the rooms to the north and west of square 174 were rearranged. During the excavation of square 174, a number of ostraca were found (one bearing the name hqtfy), adding to the numerous ostraca found there in the past, particularly in the adjacent locus 113 (“Room of the Lots”). The source of the ostraca was apparently somewhere near the Water Gate (room 1802). The concentration of ostraca in this square would seem to indicate that this might have been the site of a field office from which the communal life of the rebels was administered.

Soundings were conducted under the floors of some of the rooms of building VII, mostly on the building’s northern and eastern sides. Parts of the building were found to have undergone a variety of changes during Herod’s lifetime. Thus, in the building’s northeastern corner (rooms 152, 153, and 173), floors at a number of levels were found, as well as changes in the positions of the doorways. Remnants of bathing installations were unearthed in one of the rooms (154).

South of building VII, storeroom 177 was excavated almost in its entirety. Two distinct stages were found: the original Herodian floor, partly hewn into bedrock, and above it floors and tiny residential structures with many finds from the First Jewish Revolt. The storeroom was found to have been connected via an opening to the adjacent storeroom (176), perhaps the original entrance into storeroom 177.

Additional soundings were conducted on the upper terrace of the Northern Palace, underneath its original floor. Remains of fresco decorations in the hall (80) at the center of the residential wing were unearthed. Vestiges of walls belonging to a building which predates the Northern Palace (in room 77) are among the more important finds there. These remnants may be related to the cancelled bathhouse found under the northeastern part of the central storeroom complex.

Following the new excavations, the character of the two entrances to the northern complex during the various building stages could be clarified. During the second Herodian building stage, the southeastern entrance served as the main gateway into the storehouses and the Northern Palace, whereas the second entrance on the northwestern side was used for purely administrative purposes. During the third Herodian building stage, the entrances were bestowed greater importance. The first (to which building VIII was now attached) served the commander’s office and the reception hall, and the second was now linked to the Water Gate, which had been moved to the grounds north of building VII.

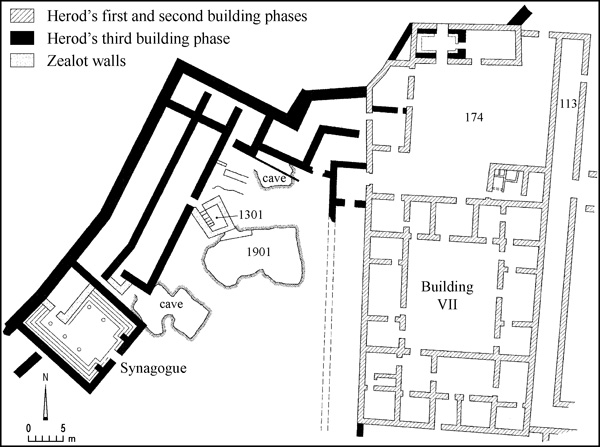

THE AREA BETWEEN THE SYNAGOGUE AND THE NORTHWESTERN ENTRANCE TO THE ACROPOLIS. A considerable part of the area between the synagogue and the northwestern entrance to the acropolis is occupied by water cistern 1901, whose roof collapsed prior to the Byzantine period. The cistern was excavated in its entirety. When the Zealots constructed ritual bath 1301 (now fully excavated) to the northwest of the cistern, a hole opened in the side of the cistern, necessitating the construction of a wall next to the damaged side of the cistern. The importance of cistern 1901 was that it could conveniently receive water brought up from the eight upper cisterns on the northwestern slope via a narrow channel that connected it to the Water Gate. Among the many finds not far above its floor is a three-line Aramaic letter having to do with bread.

Uncovered adjacent to the casemate wall and north of the cistern was a small cave that had been in use before the casemate wall was constructed. The cave was later blocked and the corridor leading to it filled with refuse, some of which dated to Herod’s reign. Among the many objects found in this cave are fragments of glass vessels, pieces of cloth, a whole woven basket, wooden implements, a sandal and other leather items, and botanical remains. Many ostraca were found in the front of the cave, as was a fragment of an amphora with an inscription mentioning “Herod king of Judea.” The inscription is similar to ones found on amphorae discovered by Y. Yadin, but more complete.

Another cave was excavated between cistern 1904 and the synagogue. The entrance to the cave had already been discovered during the 1963–1965 excavations. There is evidence in the cave for the existence of two floors, the lower of hydraulic plaster and the upper of earth. Dozens of identical, four-handled jars were set into depressions in the upper floor. The cave’s ceiling collapsed in the time of Herod, either in the wake of the earthquake of 31 BCE or during the construction of the casemate wall, crushing the jars. The cave also contained a number of rolling stones, evidence that at least some of those found on Masada date to Herodian times. The foundations of the structure that ultimately served as the Zealots’ synagogue (and apparently as a stable in Herod’s time) were subsequently built over the collapse.

The fill in room 1042, where Yadin found remnants of a genizah, was excavated in its entirety. The only find worthy of mention is a tiny scrap of blank papyrus. The floor beneath the fill appears to be contemporary to that of the adjacent cave.

THE SECTION OF CASEMATE WALL FACING THE ASSAULT RAMP. The wall tower (locus 1010) facing the assault ramp was excavated completely, as were casemate rooms 1009, 1008, 1007, and 1006. The tower and room 1009 were apparently largely dismantled when the wood-and-earth wall was built. The tops of the extant walls show signs of a violent conflagration. Among the finds discovered in this area are a complete wooden wheel (85 cm in diameter, perhaps a wagon wheel) found in room 1009 and an accumulation of sling and ballista stones, arrowheads, and an abandoned wooden beam, all found next to the rooms located south of the tower. In one of these rooms a complete wooden threshold survived. Among the material remains inside the rooms south of the tower was another pile of sling stones. North of the tower very little of the wall has remained, proof of the violent destruction wrought when the wall was breached by the Roman army.

SOUNDINGS IN THE WESTERN PALACE AND SMALL PALACES. Following the discovery of the twin Hasmonean palaces at Jericho, it was suggested that the Western Palace and the small palaces at Masada (as well as building VII, the swimming pool on the south side of Masada, and the columbarium towers) were first built during the Hasmonean period. The main purpose of the soundings conducted in 1989 was to try to establish whether or not this hypothesis is tenable. Pottery or other finds that might offer support were not found then, however, nor in further soundings conducted in 1995–2000. Whether parts of Masada were constructed during the Hasmonean period remains an open question; further excavation may someday provide a definitive answer.

EXAMINATION OF THE CISTERNS. Many of the cisterns at Masada were examined, producing no notable results. Included in this examination were the two cisterns that Y. Porath had found to be earlier than the others through analysis of their plaster (cistern 2006 on the south of the mountain and 2007 on the east). These cisterns may date to the Hasmonean period. Sedimentation pits were found next to these two cisterns, part of the rainwater collection system that fed the cisterns. The pit next to the eastern cistern is unusually large. Zealot buildings were discovered near that cistern, next to the casemate wall.

THE CHURCH COURTYARD. The L-shaped courtyard to the north and east of the church was fully exposed during the latest excavations. A tiny service structure was found in the northwestern part of the courtyard. Among the more interesting finds there were a sundial, a Greek ostracon (a letter?), glass fragments from the apse window, and a large number of roof tile fragments.

EHUD NETZER, GUY STIEBEL

THE ROMAN SIEGE WORKS

The siege apparatus built by Flavius Silva as part of his campaign against the Masada rebels is one of the best preserved from ancient times. Its three main components (eight siege camps, circumvallation wall, and assault ramp) are still visible and well-preserved today, providing evidence for the Roman army’s methods of operation. The siege works indicate careful planning and adaptation to the region’s extreme climate and topography. The Roman army presumably arrived at the site during the more hospitable winter season. Upon their arrival, the eight siege camps were erected at strategic points around the fortress. A siege or circumvallation wall, 1.5 m wide and 4.6 km long, was then constructed, connecting the camps while encircling the entire outcrop of Masada. The northern and eastern portions of this array were strengthened by roughly 13 watchtowers to compensate for the flat terrain. The purpose of this wall was to isolate the fortress and give the Romans complete control over movements to and from the blockaded area. Access was provided by means of gateways in the wall just opposite camp C, and apparently also near the “engineering yard” west of the assault ramp.

Two symmetrical sectors of the siege works can be observed. The eastern sector consists of a relatively flat area, c. 400 m below the top of the fortress. This sector was enclosed by the circumvallation wall and towers extending from the main rift-line north of Masada, along the edge of the deeply furrowed marl plains and back to the rift-line southeast of the fortress. Three small siege camps (A, C, D) were built along this stretch of the circumvallation at key points, from which the paths descending from Masada and the riverbeds around it could be observed. A larger camp (B) was set up further back from the siege line, behind camp A. It probably served as the main command post and logistical center for the entire eastern sector.

The western sector consisted of the entire relatively high area located above the fault-line cliff, extending from above the northernmost point of the eastern sector, through the furrowed and undulating area west of Masada to the fault-line southeast of the fortress. On this side, the circumvallation occasionally rises to elevations higher than even Masada itself. In this spot, as in the eastern sector, four siege camps were erected. Three small camps (E, G, and H) connected by the circumvallation wall were located at key points from which necessary crossing points could be observed. Also in the western sector a fourth larger camp was built, at some distance to the rear of the circumvallation. This camp has commonly been identified as the command post of the Roman general Flavius Silva. The most prominent component of the siege installations in the western sector is the assault ramp. It appears as a whitish, earthen rise, broad at the bottom and narrowing as it rises at a uniform slope and ends c. 13 m below the top of Masada’s precipice. The assault ramp was a vital element in the Roman offensive.

Prominent studies of the Masada siege array have been conducted by R. E. Brünnow and A. von Domaszewski (1909), C. Hawkes (1929), A. Schulten (1933), I. A. Richmond (1962), S. Gutman (1965), and Y. Yadin (1966). Most of these are theoretical, historical, and comparative studies based on an analysis of general plans, measurements, and aerial photos, rather than on results of actual comprehensive and detailed archaeological research. Limited excavations of the siege installations were carried out by Gutman at camp A and Yadin at camp F. New survey and excavations of the siege array were initiated during the summer of 1995 by B. Arubas, H. Goldfus, and G. Foerster on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and by J. Magness on behalf of Tufts University. Excavations have thus far taken place at camp F and on the assault ramp.

CAMP F. Camp F is located to the northwest of Masada, on a slope descending eastward. It consists of a large, rhomboid-shaped camp (F1) of the “playing card” type, measuring 168 by 136 m; and a smaller camp (F2) built within the southwestern corner of the larger one. It is generally agreed that the large camp was where general Silva had his headquarters, while the smaller one served the Roman garrison that was stationed at the site, according to Josephus (War VII, 407), after the siege of 73–74 CE came to an end. Stones from parts of camp F1 were used in the construction of F2’s eastern and northern walls, as well as for the buildings inside the camp.

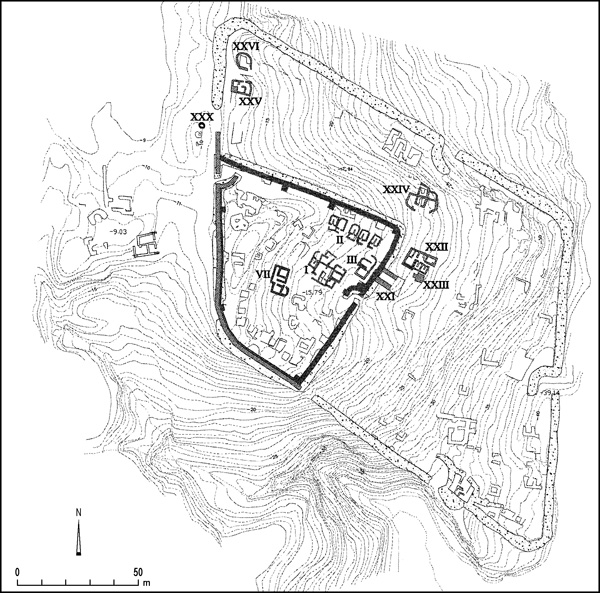

Camp F1 (The Large Camp). In addition to the structure excavated by Yadin adjacent to the south gate, four buildings (units XXI–XXIV) at the center of the camp have now been fully excavated; parts of two others in the camp’s northwestern corner (units XXV–XXVI) have also been excavated.

Unit XXI is a three-sided rectangular structure open to the east. It is located in the center of the camp, facing its eastern gate (porta praetoria). In front of it lies a paved open area from which a lane (via principalis) leads to the northern and southern gates of the camp. The structure was poorly preserved due to the construction of the eastern wall of the later camp, F2, which still covers the structure’s western wall. It has exceptionally thick walls, c. 2 m wide, and is commonly identified as the “commander’s tent” mentioned by Josephus. Its thick walls are regarded as the typical U-shaped couches of a triclinium. A similar structure stood at the center of camp B in the eastern sector.

Unit XXII is located next to and northeast of unit XXI. It was also damaged considerably due to its proximity to camp F2. It is rectangular in plan and divided into three parts: the northern wing was a service area with a number of installations and cooking facilities; the southern wing was residential, containing two triclinia; and the western wing was a broad room with a solidly built stone platform in its northern corner. A narrow corridor leading from the entrance to the western wing separated the southern and northern wings. Among the finds in the building were delicate glassware and painted Nabatean pottery. It is likely that the building served as the quarters of the legion’s senior officers.

Unit XXIII was unearthed near the southeastern corner of unit XXII. It is a solid, square platform, 3 by 3 m. Its box-like walls were of partially dressed fieldstones averaging 0.3 by 0.4 m. It was filled with fieldstones and gravel. Found attached to its western side were remnants of a built ramp ascending to its flat top. The structure has been identified as the tribunal, the stage on which the commander stood when addressing his troops. An identical structure was found in the center of camp B.

Immediately to the north of these buildings is Unit XXIV. The center of this structure consisted of two triclinia built back-to-back. From the corners of the triclinia extend semicircular stone fences forming courtyards around the rooms. The building is one of the prominent structures found throughout the camp that apparently served as quarters for infantry or cavalry officers. They are located in positions that would have stood at the ends of long rows of soldiers’ tents extending along the length and breadth of the camp. Another such structure is unit XXV, only partially excavated, located on high ground dominating the northwestern part of the camp. It stood at the western end of what were rows of soldiers’ tents, and was separated from them by a terrace wall that forms a high step in front of its entrance on its northern side. The structure, roughly 8 by 5 m, is divided into two main parts by an L-shaped wall in front of the entrance and a short wall to its right. An opening at the western end of the eastern part leads into an L-shaped tripartite space. A solid square stone platform in the southwestern corner of the building has square spaces to its left and right. This arrangement and the rich pottery finds, reminiscent of those in unit XXII, attest to the importance of the building. It may have also served as officers’ quarters for the unit occupying this part of the camp.

Unit XXVI, immediately to the north of unit XXV and at a lower level, was also only partially excavated. It is located at the curved juncture of the northern and western intervallum in the northwestern corner of the camp. The structure is unusual in having a rounded external wall with an opening to the south. Clearance of massive debris revealed a rectangular stone-paved interior space surrounded by benches. The function of the building has not yet been determined.

Camp F2 (The Small Camp). As mentioned above, camp F2 was constructed inside camp F1 and occupies its southwestern part. Some 30 structures with roughly built stone walls were clearly visible in the camp. Most of these were relatively small structures measuring roughly 5 by 3 m and composed of two compartments: a living space fronted by a service area. They were probably substructures underlying tents arranged in a continuous peripheral line along the camp wall. The open central space of the camp was dominated by a few larger central structures. Four architectural units (units I–III and VIII) were excavated; they join the roughly 16 units previously excavated by Yadin’s expedition along the southern section of the camp. One structure was come upon (unit XXX) outside both camps.

The camp’s walls were also surveyed and examined. Parts of camp F1’s western and southern walls were incorporated into camp F2. The eastern and northern walls of camp F2 had to be constructed de novo, using materials from nearby structures and parts of walls belonging to the earlier camp. All walls were reinforced with towers and gangways. The camp possessed two clavicle-type gates: one in the middle of the eastern wall; and the other, once camp F2’s western gate, in the northwestern corner.

Unit I, an unusually large (15 by 13 m) and complex building with 10 rooms, is located in the central open space just in front of the eastern gate of the camp. It was excavated nearly in its entirety. Its rooms yielded a very large amount of collapsed stone and attest to two building phases. The building has a central square nucleus (c. 8 by 8 m) consisting of two elongated rooms with benches, an anteroom on the southwestern corner, annexes, and storerooms. It is possible that structural elements dating from the construction of the large camp were integrated into the building. The rich finds include jars, cooking pots, a few luxury vessels such as Nabatean bowls and glassware, and some coins. One of the annexes was outfitted with a triclinium. The unique features of this building allow it to be identified as the garrison’s headquarters.

Unit II is located immediately to the north of Unit I or the headquarters building, between it and the camp’s northern wall. It is a complex of six similar buildings arranged in a row and facing the interior of the camp, each consisting of an anteroom and a main triclinium-shaped room. Most of the anterooms contained cooking areas with much pottery, whereas only meager finds were recovered from the triclinia. Metal objects associated with cavalry were among the finds.

Unit III is to the east of the headquarters building, in close proximity to the camp’s eastern wall, near the corner of the wall and the clavicle of the east gate. The building appears to have had two stages. Its first stage consisted of a square chamber sunken into the ground and entered from its northeastern corner. The structure’s meticulously planned construction is unusual in the context of the entire siege works, its solid walls heavily coated on both sides in whitish plaster. It seems very likely to be coeval with the large camp, having thus formed part of its praetorium compound or camp headquarters, since it lay just 2 m from the back side of the “commander’s tent,” unit XXI. It was later intentionally filled with stone debris and packed earth, virtually devoid of finds, and its floor level was raised. Also during this second stage, a room and an anteroom were added to the north. Abundant pottery was found amid the remains of the second stage.

West of unit I and in the center of the camp is unit VII. The second largest building (12 by 6 m) in the camp, it was obviously of considerable importance. Its entrance, on the eastern side of the building, leads to a service corridor with cooking hearths. The corridor divides the building into two wings: the southern wing is a single square room, and the northern an antechamber in front of another square room. To the left of the entrance is an opening to a small oval cell that probably served as a storage room. The building may have housed some of the garrison’s functionaries.

Unit XXX consists of three piles of stones visible on a small knoll immediately outside the camp’s northwestern corner, c. 5 m west of the western wall of the camp. The piles are arranged in a north–south row. The ground surrounding them is black, apparently the result of a thick concentration of ash and rubbish. The northernmost pile of stones was excavated, revealing an underground oval installation paved with stone slabs. Its incurving walls indicate that it had a dome-like shape. It was evidently one of three ovens serving the main kitchen of the large camp or the garrison.

The finds discovered in the buildings of camp F2 have made chronological differentiation between the two camps possible. R. Bar-Nathan’s preliminary analysis of the pottery found during Y. Yadin’s excavations in the small camp has shown that it is identical to pottery from a number of loci on Masada ascribed to the Roman garrison. Some of the types were in use up to the beginning of the second century CE. Coins from the same period were also found, ranging from 106 to 113 CE; another group of coins dated to 73/74 CE represents the end of the First Jewish Revolt. While it is almost impossible based upon archaeological evidence to prove or disprove the presence of the garrison stationed by Silva immediately after the fall of Masada, it is feasible that a garrison was posted at camp F2, as well as atop Masada, between 106 to 113 CE. The circumstances of such a short presence may have been related to events in the period, beginning with the annexation of the Nabatean kingdom to the Roman Empire in 106 CE and lasting until Trajan’s preparations for the Parthian War in 113/114 CE.

THE ASSAULT RAMP (AREA R). In order to examine the infrastructure, composition, and construction of the assault ramp, two probes were conducted on the ramp’s northern and southern slopes. Due to logistical difficulties, neither reached bedrock. However, a careful examination of the topography and morphology of the area around the ramp, combined with Josephus’ description, provide good indication of what the Romans coped with in planning the final stage of the siege.

The ramp is located at the easternmost end of a ridge that is the watershed between

Local building materials were utilized in the construction of the ramp. Tamarisk branches and date palms found growing in the area were used, though neither extensively nor consistently, and mostly in the ramp’s lower part. Construction relied on branches and short pieces of wood, sometimes placed transversely to pack the stones and soil together, while most of the ramp structure was found to consist of irregular chalky blocks quarried from the natural knoll next to the bottom of the ramp. The base of this knoll became part of the lower, western portion of the ramp.

Archaeological evidence for Josephus’ description of the final stages of the Roman assault operation remains inconclusive. According to Josephus, an enormous assault tower (60 cubits high) was built on a large stone-built platform (50 cubits wide and 50 cubits high). Out of this ironclad tower the Romans attacked the walls of Masada with missiles and ballistae before finally breaching the walls with a battering ram. No sign of such a platform was found atop the ramp, nor were there indications of a conflagration or artifacts associated with assault operations such as the arrowheads, missiles, or ballista balls found at Gamala, Yodfat, Lachish, and Apollonia-Arsuf. The absence of a large segment of the casemate wall above the ramp extending to the western gate (including the gate itself), commonly interpreted as evidence of the Roman breach, could be a result of later building activity, as this was the central area of the Byzantine laura. Moreover, it is generally agreed that the assault ramp in its present state would not have been adequate to achieve its final goal. A common explanation for this is that heavy erosion has reduced the ramp to a third of its original size. Yet, if such were the case, other components of the siege works should have been more severely damaged. Geomorphological and climatic conditions of the region also do not support these claims of massive erosion. Rather, it is believed that this ramp has endured only minor change since it was constructed by the Romans and was never operational.

BENNY ARUBAS, HAIM GOLDFUS

The Coins

The Epigraphic Finds

Historical Studies

EXCAVATIONS ON THE SUMMIT

Supplementary excavations were conducted by E. Netzer and G. Stiebel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem upon the summit of Masada over several seasons spanning 1995–2000, as part of a development project undertaken by the Israel Ministry of Tourism and the Nature and Parks Authority. It followed a short season conducted by Netzer in 1989.

Main discoveries in the latest excavations at Masada are floors and assemblages datable to the Herodian period. The rich epigraphic finds include bilingual (Greek and Latin) inscriptions and ostraca from the time of the First Jewish Revolt. These may shed further light on the rebels’ communal life. New information has emerged concerning the entrances to the “acropolis” and on the area adjacent to the synagogue and cistern 1901.