Migdal, Ḥorvat

THE SITE AND ITS IDENTIFICATION

EXCAVATIONS

In the 1970s and 1980s brief surveys of the site and its vicinity were conducted by S. Dar, Z. Ilan, and D. Pringle. From 1987 to 1991, a systematic survey of agricultural and industrial installations was conducted by E. Ayalon on behalf of the Eretz-Israel Museum in Tel Aviv. During the years 1989–1994, five seasons of excavations were carried out at the site under the auspices of the Eretz-Israel Museum and the Texas Foundation for Archaeological and Historical Research, under the direction of E. Ayalon, W. Neidinger, and E. Matthews, with the participation of Y. Dray. The excavations were concentrated in the outskirts of the village to the east (area A) and south (areas B and C), and in the industrial area to its northwest (area D). In 2001, O. Sion and O. Marder, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, excavated prehistoric remains as well as agricultural and industrial installations in the center of the spur.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE EARLY PERIODS. The site was occupied to a limited extent in the Chalcolithic period, Early Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age II, and Late Bronze Age. It was expanded in the Iron Age, from the eleventh/tenth century BCE onward. Although no buildings from this period have been preserved, stone fills found in many areas, particularly area B, contained a large quantity of Iron Age sherds.

THE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD. The discovery in areas A and B of sherds of the Persian, Hellenistic, and Early Roman periods, including imported ware of the red-figure, black-figure, black-glazed, and terra sigillata types, and fragments of a polychrome fresco, indicates the presence on the site of wealthy residents. The early buildings, some of which were constructed of ashlars with marginal dressing, were destroyed in a great conflagration. On their floors lay smashed pottery and a coin of 68 CE, as well as a fragment of a krater made of soft limestone. This was probably a Jewish settlement that was destroyed in either the First or Second Jewish Revolts against the Romans. In area B, beneath the Byzantine monastery (see below), was a secret hideout consisting of a number of cisterns interconnected by openings cut in their walls and a narrow winding subterranean entrance corridor; the frame of a door (0.70 by 0.70 m) was hewn in the corridor. In area D, a first-century CE potter’s kiln was uncovered.

THE ROMAN PERIOD: THE SAMARITAN SETTLEMENT. Settlement at the site was renewed in the second–third centuries CE, apparently by Samaritans, as is evidenced by the “Samaritan” sarcophagi found in burial caves on the spur and the numerous Samaritan lamps recovered in the settlement. A bathhouse exposed in area A was almost completely destroyed in a later period. In area B, beneath the synagogue, were found well-planned and well-built structures, grouped in three rows. Some of the buildings were preserved to a height of 1.5 m.

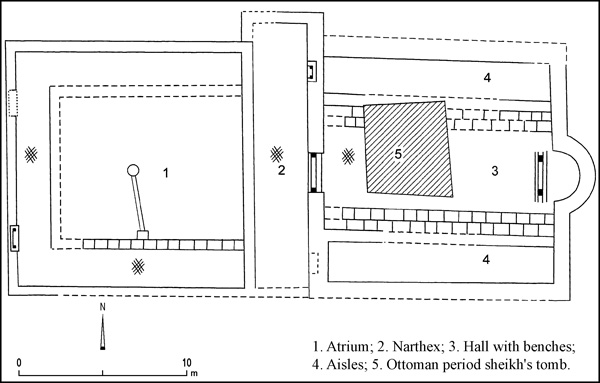

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. In area A, two rows of adjacent structures with cellars and various installations were uncovered along a 35-m stretch. A lane ran alongside the houses. In area B, on a spot commanding an unobstructed view, a synagogue was erected at the end of the fourth or beginning of the fifth century CE. The synagogue consisted of three components oriented west–east and facing Mount Gerizim: an atrium, a narthex, and a hall. The atrium (15 by 15 m), paved with crushed chalk, was entered from the west through two entrances approached by a wide staircase. A cistern was located in its center. The edges of the atrium were plastered and covered with a roof supported on limestone pillars. The narthex (16 by 3.2 m) was paved with a white mosaic. In the rectangular hall (internal measurements 13.5 by 7.5 m), carpeted in a fine multicolored mosaic, were two rows of ashlar benches along the walls. On the inside of the wide threshold was a mosaic medallion containing an incomplete inscription in flawed Greek: “Let them be remembered, the sons of the village of Antesion, Theotis and Julos, and…” The mosaic carpet was decorated on both sides of it with columns, pomegranates, and fine floral motifs. The main carpet of the hall was destroyed but its border survived; it consists of acanthus medallions enclosing fruits and plants in a style closely resembling the mosaic in the Samaritan synagogue at Khirbet Samara. The building had a tile roof that was probably constructed, among other species, with cedar beams that were found in secondary use in later buildings on the site. Next to the synagogue were two narrow, adjacent rooms. A mikveh north of the narthex, which was paved with a white mosaic, was probably used by visitors to the complex.

Exposed on a lower terrace to the west was an industrial olive-oil press with a crushing mill and two beam-and-screw presses. Alongside the press were two additional mikvehs, one partly paved with a multicolored mosaic. A similar olive-oil press was uncovered to the west (in area C). In the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century CE, changes were made in the synagogue hall, the major being the removal of the benches along the eastern wall and the construction of a small apse (3.5 m wide, 1.5 m deep) of excellent ashlar masonry. A limestone chancel screen with a carved guilloche decoration stood in front of the apse.

The sixth century CE saw major changes in the settlement and a significant reduction of its size, probably as a result of the Samaritan revolts against the Byzantines. In area A, all the buildings were abandoned and the area became a refuse dump into which an enormous number of vessels and sherds were discarded, including approximately 100 Samaritan lamps and a large iron plowshare fitted with ground-sweeps (“ears”). In area B, the synagogue no longer functioned as such. The mosaic pavements in the center of the hall and in the apse were systematically removed and replaced by a floor paved with stone slabs (including reused architectural elements from the synagogue), clay, and plaster. The nearby mikveh was turned into an industrial facility. The sides of the atrium were now paved with a simple colored mosaic bearing a cross design, laid on a pedestal or an anchor; and the staircase on the western side leading to the atrium was dismantled. On the lower terrace to the west, a large well-planned complex (at least 35 by 30 m), apparently a monastery, was constructed. It consisted of a central court (12 by 8 m) surrounded by cells, long rooms, and halls, probably storerooms in which various installations were built. Two or three phases of renovations and repairs were distinguished in the rooms. The courtyard was entered from the north (from a lane?) through a large threshold (2.6 m long) bearing worn traces of a carved geometrical design that was apparently the original lintel of the synagogue building. The olive-oil press remained in use but the two mikvehs adjoining it were discontinued and paved over. There was a chapel somewhere in the complex, perhaps in the synagogue, as is evidenced by the discovery in the debris of the later complex of three marble chancel posts with holes in the top, into which metal crosses were inserted. In one of the rooms that served as a storeroom were found a fragment of a round marble table and fragments of a basalt “donkey mill”; the upper grinding stone was decorated on both sides with an incised seven-branched menorah. It seems that the Samaritans originally operated the mill near the synagogue, and in a later period the upper millstone was reversed and the menorahs were turned upside down. In the northern edge of the courtyard, an impressive stepped entrance was installed leading into the Second Temple period secret hideout that was now turned into a storage area with side compartments. The rooms of the monastery yielded pottery vessels that were uniform in appearance, among them fine wine cups, cylindrical-shaped jugs (for oil?), and a lamp decorated with a palm tree and a cross.

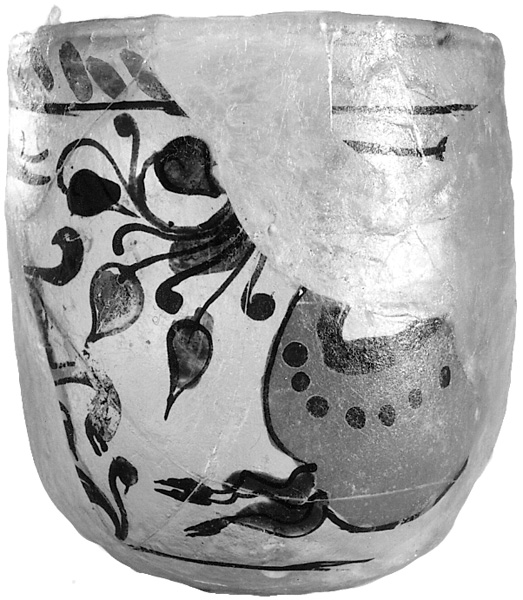

THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD. Area A was not inhabited and the synagogue and eastern wing of the monastery were no longer in use in the Early Islamic period. Only the western part of the monastery still functioned. Several rooms were vacated and their contents were thrown into the subterranean complex. On top of the disused Byzantine olive-oil press, a rectangular tower (13 by 11 m) was erected, consisting of a ground floor filled with earth and a second floor with four rooms, several of which had flagstone floors. In one of the rooms the foundations of a flight of stairs leading to the roof or to another story were uncovered. The tower apparently served as a guardroom and lookout post. To its east a small room with a mosaic pavement decorated with plain colored rhombuses may have been a dining or prayer room. South of the tower was a row of rooms resembling barracks, their floors plastered. The finds from all these components date to the seventh–eighth centuries CE. Among the contents of a small refuse pit were intact lamps, ivory objects, and a rare glass cup from the eighth century CE, decorated with floral and faunal designs in the luster technique. In area C, west of the tower, the olive-oil press continued in use until the eighth century CE; a cedar beam in secondary use was part of its structure. At some time during this century, the entire site was abandoned, only to be resettled in the Mameluke period. The sheikh’s tomb built above the synagogue hall in the Ottoman period and the graves dug around it caused considerable damage to the early structure.

SURVEY RESULTS. The systematic survey conducted on the spur in an area of about 3 by 1 km uncovered numerous remains of agricultural activity, such as fenced-in fields and terraces; stone quarries; lime kilns; hydraulic, agricultural, and industrial installations; burials; and paved roads from the Roman and Byzantine periods, including a section of the Sebaste–Apollonia road. At ‘En Dardar evidence was found of advanced irrigation farming. One hundred and twenty winepresses from all periods and 25 open-air olive-oil presses attest to the principal crops grown. The survey encountered similar groups of installations all over the spur; each consisted of a winepress, an olive-oil press, a cistern, and a tomb. In an area not damaged by development activities, about 30 groups of this type were identified; they apparently represent the division of the spur into separate family plots. In the industrial area (D), a round rock-cut columbarium was found, as were the remains of an extensive glass industry. Excavations at the site did recover large amounts of raw material for the production of glass vessels and fragments of glass objects, probably collected for recycling.

ETAN AYALON