IDENTIFICATION

Moza is first mentioned in the Bible as one of the cities of the tribe of Benjamin (Jos. 18:26). The identification of the site is important for establishing the location of the border between the territories of Judah and Benjamin in this area. One of the sons of Caleb is called Moza (1 Chr. 2:46); the name also appears in the genealogy of Zimri, one of the heads of the tribe of Benjamin (1 Chr. 8:36–37; 9:42). The meaning of the name is “water source.” Based on the similarity with the name of the Arab village Khirbet Mizza, the biblical settlement has been identified by a number of scholars with Moza; others have equated it with Khirbet Beit Mizza, located at Mevasseret Zion, a short distance to the north. The results of the latest excavations at the site, however, conclusively confirm the identification of the biblical site with Moza.

HISTORY OF THE SITE

A seal known to have been found near Moza published by E. Sukenik suggests that Moza was an area of vineyards and wine production during the Hasmonean–Early Roman period. Moza occurs in the Mishnah: “Below Jerusalem there is a place named Moza. [On the eve of Hoshanah Rabbah] they go down and cut willow shoots there to place at the sides of the altar” (Mishnah Suk. 4:5). After the destruction of the Second Temple, the Romans, by order of Vespasian, settled a colonia of 800 veterans in the district of Ammaus, about 30 stadia from Jerusalem (Josephus, War VII, 217). Some scholars have identified this Ammaus with the village called Emmaus in the New Testament (Luke 24:13), but this identification is disputed. Moza has been identified with Talmudic Kolonia (B.T. Suk. 45a; J.T. Suk. 54b). The name of the colony of Roman soldiers was apparently preserved in the name of the Arab village Qaluniya, abandoned in 1948.

The site of Moza extends over a large area that includes the western bank of

EXCAVATIONS

In 1887, C. Schick excavated a tomb decorated with frescoes from the third century CE on the bank of

At the beginning of the 1960s, O. Bar-Yosef and others conducted an archaeological survey at the site and discovered flint tools of the Neolithic period, mostly Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, dispersed over the area south of the present highway. In 1962, V. Sussman excavated shaft tombs containing Middle Bronze Age II remains in

| STRATIGRAPHY OF MOZA | Stratum | Period | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Ia | Ottoman | 16th–20th centuries CE |

| Ia | Post-Byzantine | post-7th century CE |

| II | Byzantine | 6th–7th centuries CE |

| III | Hellenistic | 2nd century BCE |

| IV | Iron IIC | 7th–beginning of the 6th centuries BCE |

| V | Iron IIB | 8th century BCE |

| VI | Iron IIA | 10th–9th centuries BCE |

| VII | Iron I/Iron IIA | 11th–10th centuries BCE |

| VIII | MB | 18th–17th centuries BCE |

| IX | EB IA | 35th–34th centuries BCE |

| X | Pottery Neolithic | 6th millenium BCE |

| Upper XI | Middle PPNB | 9,000–8,300 |

| Middle XI | Middle PPNB | 9,000–8,300 |

| Lower XI | Middle PPNB | 9,000–8,300 |

| Upper XII | Early PPNB | 9,400–9,000 |

| Middle XII | Early PPNB | 9,400–9,000 |

| Lower XII | Early PPNB | 9,400–9,000 |

ZVI GREENHUT, ALON DE GROOT

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE PREHISTORIC PERIODS. In five excavation areas opened along two agricultural terraces, prehistoric remains were uncovered in two sub-areas of area B, where excavations were extended beneath the Bronze Age remains down to bedrock. Three Neolithic strata were exposed, the lowest stratum from the early phase of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, the next from the middle phase of that period, and the upper equivalent to the Lod Culture of the Pottery Neolithic period (Jericho IX).

The Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period. The stratum dated to the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period is divided into four sub-phases exposed in two sub-areas. In the northern sub-area, the earliest phase is represented by remains of walls and fallen stones lying on bedrock, and of a structure with a bedrock floor covered in a thin plaster surface. In the southern sub-area, a massive curved wall (1.1 m thick) of a circular building apparently 8 m in diameter was uncovered; it was only partly cleared. The building’s floor was of packed earth. An adult burial lacking the skull had been dug into the floor.

The subsequent phase in the northern sub-area is represented by the remains of a rectangular structure composed of thick plaster floors and mud-brick walls. Only its foundations were preserved. The plaster floors reached the walls of the structure and in several spots rose to join walls that did not survive. In the eastern part of this area was a burial ground containing primary and secondary graves. Most of the burials were laid in plaster paste. The graves appear to have been marked by a tombstone or the jaw of a carnivore. Between the burial area in the east and the plaster floors in the west, a cache of 60 flint blades was found; these may have been placed inside a wooden or leather box and buried beneath the foundations of the rectangular building. Also attributed to this phase is a thick wall (1.2 m wide) in the southern sub-area. The wall crossed the excavated area in a north–south direction and may have served as a boundary wall. A living floor composed of small stones with a high concentration of flint and animal bones is associated with it.

The next phase in the northern sub-area includes an arc-shaped structure with a burnished white plaster floor with traces of red paint surviving in several spots. A hearth and a section of a wall, not part of the arc-shaped structure, were also uncovered from this phase, along with a well-made yellowish plaster floor exposed in the eastern part of the area. The phase is represented in the southern sub-area by a long wall, 1 m wide, which crosses the area from north to south. In the center of the area were exposed three circular installations and one ovoid-shaped, all lined with small stones. Two of these appear to have been used for burning lime for the production of plaster. Between the installations was the grave of a young individual laid in a plaster paste. Uncovered in the eastern part of the area were the remains of walls, sections of a plaster floor reaching the walls, and two circular stones that apparently served as column bases.

The upper phase in the northern sub-area is comprised of the remains of two rectangular structures with thick, well-made plaster floors that reach the walls. An infant burial was found under the floor of one of the houses. Sections of walls, plaster floors, and hearths also belonged to this phase. A round pit in the northeastern part of the area contained the bones of two aurochs (Bos primigenius); many of the bones were still articulated. The upper phase of the southern sub-area contained sections of walls, installations, and hearths.

The flint assemblage from this stratum consisted of a large percentage of Helwan points along with Jericho points, sickle blades, and bifacial tools, some with tranchets. A rich assemblage of obsidian was also recovered, and includes all the main components of the industry—cores, flakes, blades, and tools. Faunal remains, including those of rodents and birds, were also found in abundance. Other finds were bone tools, a number of figurines, beads of green stone, and bracelets made of stone and shells.

The Middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period. The stratum from the middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period is divided into three phases that are separated from one another by a thin layer of gravel. The layers are not of uniform thicknesses. In the northern sub-area the remains were well preserved; those in the southern had been disturbed by Iron Age walls and Middle Bronze Age pits. Two rectangular structures from the early phase of this period were uncovered on a slope in the northern sub-area. The floors were made of beaten earth covered with yellowish-white plaster laid above a bedding of small stones. Beneath the floor of one of the structures was an infant burial that included the skull and upper limbs. In the southern sub-area, sections of very fragmentary walls were uncovered, as were parts of plastered floors, a hearth, and abundant faunal remains.

The subsequent phase in the northern sub-area is represented by two round installations, sections of fragmentary walls, and a layer of gravel. In the southern sub-area this phase consisted of a north–south wall, and to its north, a plastered floor on a gravel bedding. The upper phase of this stratum was represented on the eastern side of the northern sub-area by floor segments of earth and plaster, numerous gravel layers with charred stones, a round built installation, and a gravel pit. Between the gravel layers and the installations were found sections of fragmentary walls. In the southern sub-area, the upper phase consists of a yellowish plaster floor.

This stratum contained rich assemblages of flint implements and animal bones. Outstanding among the flint tools are arrowheads of the Byblos, ‘Amuq, and Jericho types. The sickle blades were formed on naviform blades and retouched with delicate inverse retouch. Among the bifacials, the axe is the most common tool. There was also an impressive assemblage of bone tools, a small amount of obsidian tools, and stone and shell jewelry. The flint assemblage is homogeneous and characteristic of the middle phase of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period (9000–8300

The Pottery Neolithic Period. The Pottery Neolithic period was only exposed in the northern sub-area. Sections of fragmentary walls were discovered; next to one wall was a row of three

HAMOUDI KHALAILY, ANNA EIRIKH-ROSE

THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES AND LATER PERIODS. Remains of the Bronze and Iron Ages and later periods were uncovered in five excavation areas along the two agricultural terraces, over a total area of about one-third of an acre. A sixth area, F, was opened on the eastern side of the spur, where the spur meets

The Early Bronze Age IA. A wall of the Early Bronze Age IA was found next to a rock-cut work surface with cupmarks. Two round installations (0.8 m and 1.3 m in diameter) paved with small stones were also found. Among the objects recovered on the hewn surface were sherds of a hole-mouth jar and an Early Bronze Age IA bowl. An elliptical pit was filled with a mixture of gravel and a large quantity of sherds from this period. The ceramic assemblage is similar to that uncovered in Eisenberg’s excavations in the area of the modern highway.

The Middle Bronze Age II. Part of a structure of the Middle Bronze Age II was found in area A. Two building phases were distinguished in the structure; a gray beaten-earth floor was attributed to the early phase and a floor paved with stone slabs to the later. The plan of the building could not be ascertained. In the northern sub-area of area B, above the remains of the wall from the Early Bronze Age, a hearth containing Middle Bronze Age II sherds was uncovered. Dating to the same period was a wall built of two rows of hewn fieldstones and severed by Iron Age construction. In the southern sub-area, disparate fragments of a wall were exposed and apparently date from this period.

The Late Bronze Age. Pottery of the Late Bronze Age, consisting mainly of sherds of Cypriot milk bowls and other decorated ware, were found in fills in areas B and D, providing evidence for occupation of the site in this period.

The Iron Age I–IIA. Remains of the Iron Age I–IIA were uncovered only in the southern sub-area of area B. These include a floor paved with stone slabs, above which were stone and pottery installations and a beaten earth floor. Both were buried under a thick conflagration layer. On the floors and under the conflagration layer were found a pyxis, cooking pot, and cooking jug characteristic of the eleventh–tenth centuries BCE, a date confirmed by 14C dates from this stratum. The destruction of the stratum may be related to Shishak’s campaign in this part of Canaan. A typical seal of the period depicting antithetic horned animals was also found.

The Iron Age IIA. Exposed above the conflagration layer in the southern sub-area was a room with a semicircular stone installation in one corner; and a row of three stone installations, two of them square and covered with yellow plaster and one round and unplastered, adjoining its eastern wall. The rooms and installations yielded pottery of the tenth–ninth centuries BCE. To this period were also attributed four silos in the northern part of area B, dug into the earlier fill of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages.

The Iron Age IIB–C. The majority of the finds discovered at the site belong to the period between the eighth century BCE and the destruction of the First Temple. These consist mainly of a group of 36 round and elliptical stone-lined silos dug into bedrock. The silos were uncovered in areas A and D in the middle of the site. The round silos vary in diameter (1–2 m); the elliptical ones are slightly larger (1.8–2.5 m long, 1.4–1.8 m wide) and appeared only in area D, the western part of the area with the silos. All were built of small fieldstones in dry construction; two also incorporated long, narrow stones. Some were paved with stones, a number were plastered on the bottom, and one was also plastered on the sides. The stone base of a wooden column that supported the roof was uncovered in many. Not all the silos were in use contemporaneously, and several phases of construction can be discerned, with a number of them having been dug into earlier silos and replacing them, indicating that the area was in use over a long period of time. They were later turned into rubbish pits, into which a large quantity of sherds, mostly of bowls, was discarded. Because the contents of the rubbish pits postdate the silos, it is difficult to establish the date of the silos. Nevertheless, since their abundant ceramic contents date to the ninth–eighth centuries BCE, it can be concluded that the silos were in use up to the eighth century BCE.

Also ascribed to this period is a structure on the lower terrace of area A, built against a bedrock terrace to its north. The building consisted of a main room (3.9 by 4.4 m) that probably served as a storeroom, as it contained a large amount of hole-mouth jars typical of the period. The jars lay shattered on the floor in a manner suggesting that they had been stored on shelves along the walls. In area B, walls and plaster floors associated with them were attributed to this period; alterations to these features indicate an extended period of use of the buildings in this phase. Eleven clay loom weights typical of the period were found on one of the floors.

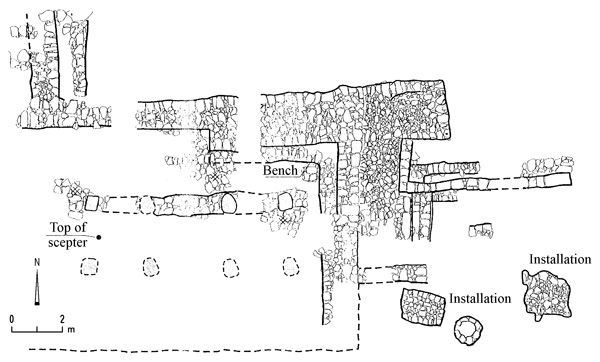

To the last phase of the Iron Age (seventh–sixth centuries BCE) is assigned a structure in the eastern part of the excavated area, on the upper slope of area A. It contained a long rectangular room (9.7 by 2.1 m) paved with stone slabs. West of this room was found the southern part of another room, and northeast and southwest of it were fragments of additional wall segments. In area B, on the upper terrace, another structure of this phase was exposed, the northern wall of which was a massive retaining wall (2 m wide) that formed an offset in its eastern façade. The structure was a columned building oriented east–west. Its entrance, facing east, was approached from a courtyard by a three-stepped staircase. The courtyard’s floor was made of crushed chalk and contained the remains of installations, including a rectangular surface (1.9 by 1.2 m) and round installation (0.6 m in diameter). On the floor was a stylobate that incorporated three column bases. If a fourth column is reconstructed, the columns would have been placed at equidistant intervals of 2.5 m. A second row of columns may have stood in the southern part of the room, where the floor was washed away due to its location on the slope. Similarly, the southern wall of the building may have had another offset. According to this proposed reconstruction, the plan of the building resembled a megaron, its interior divided into three equal long spaces. A bench was built against the wall in the northeastern corner. In a layer of ash on the floor of the building was found the top of a scepter made of Egyptian blue; it is in the form of a pomegranate on three rings, which surmount three rows of six overhanging petals. The raw material and the style of the scepter display a strong Phoenician-Syrian-Mesopotamian influence. South of the building lay a great heap of stone debris, probably the result of the building’s collapse after its abandonment. In the debris were found numerous sherds from the end of the Iron Age, noteworthy among which were two with inscriptions in ancient Hebrew script, one on the rim of a hole-mouth jar,

The finds uncovered in the excavations at Moza are typical of the Judahite material culture in the Iron Age. They include pottery zoomorphic and “pillar” figurines, common in Judah in this period; two jar handles with lamelekh seal impressions; six jar handles incised with a concentric circle design; and four rosette seal impressions, one on the handle of a decanter and the others on jar handles. Also retrieved were a scaraboid clay seal with a palmette design characteristic of Hebrew Iron Age II seals, a scaraboid seal impression of a sphinx, and numerous handles of cooking pots incised with potters’ marks.

Moza was an important site and held a unique position in the Iron Age, when it served as an administrative center of the Judahite kingdom in the Jerusalem region. After the destruction of the Temple, occupation on the Moza spur came to an end, and the center of the area’s settlement moved elsewhere.

The Later Periods. Uncovered in the southern sub-area of area A was part of a room carved out of bedrock, apparently belonging to a freestanding structure. It contained fragments of red plaster and sherds of the Byzantine period. South of the room half of a round lime kiln (about 2.5 m in diameter) was excavated; it blocked the entrance to the Byzantine period rock-cut room and therefore postdates it. Judging from sherds recovered in the fill under the walls, the kiln may have been contemporaneous with terrace walls that are dated to post-Byzantine times, perhaps the Ottoman period. In area F, located in the Sorek Valley east of the site, a spring issuing from a tunnel carved out of the rock face was rediscovered. In front of the spring and rock was a network of plastered pools separated by walls. Also uncovered was a plastered channel that carried water to one of the pools. This network of pools, the channel, and walls belong to a single period of construction that took place during the Crusader or Ayyubid periods, based upon 14C dates. The entire complex underwent alterations, including the building of walls, the blocking of one of the pools, the addition of a plastered floor, and the laying of a clay water pipe to convey water from the spring to the area north of the spring.

ZVI GREENHUT, ALON DE GROOT

IDENTIFICATION

Moza is first mentioned in the Bible as one of the cities of the tribe of Benjamin (Jos. 18:26). The identification of the site is important for establishing the location of the border between the territories of Judah and Benjamin in this area. One of the sons of Caleb is called Moza (1 Chr. 2:46); the name also appears in the genealogy of Zimri, one of the heads of the tribe of Benjamin (1 Chr. 8:36–37; 9:42). The meaning of the name is “water source.” Based on the similarity with the name of the Arab village Khirbet Mizza, the biblical settlement has been identified by a number of scholars with Moza; others have equated it with Khirbet Beit Mizza, located at Mevasseret Zion, a short distance to the north. The results of the latest excavations at the site, however, conclusively confirm the identification of the biblical site with Moza.

HISTORY OF THE SITE

A seal known to have been found near Moza published by E. Sukenik suggests that Moza was an area of vineyards and wine production during the Hasmonean–Early Roman period. Moza occurs in the Mishnah: “Below Jerusalem there is a place named Moza. [On the eve of Hoshanah Rabbah] they go down and cut willow shoots there to place at the sides of the altar” (Mishnah Suk. 4:5). After the destruction of the Second Temple, the Romans, by order of Vespasian, settled a colonia of 800 veterans in the district of Ammaus, about 30 stadia from Jerusalem (Josephus, War VII, 217). Some scholars have identified this Ammaus with the village called Emmaus in the New Testament (Luke 24:13), but this identification is disputed. Moza has been identified with Talmudic Kolonia (B.T. Suk. 45a; J.T. Suk. 54b). The name of the colony of Roman soldiers was apparently preserved in the name of the Arab village Qaluniya, abandoned in 1948.