Nebi Samwil

INTRODUCTION

Nebi Samwil is located c. 7 km northwest of Jerusalem. It covers a total area of 5 a. and, at an elevation of 908 m, overlooks the main road from the Coastal Plain and western Samaria to Jerusalem. Its position has given it strategic importance since ancient times, and it has served as a military fortress and holy place for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Excavations were conducted at the site during the years 1992–2003 under the direction of Y. Magen, with the participation of M. Dadon, on behalf of the Staff Officer for Archaeology in Judea and Samaria.

IDENTIFICATION

The identification of the site of Nebi Samwil with biblical toponyms has been a matter of dispute. Medieval Jewish sources identified the site as Rama, the burial place of the Prophet Samuel (1 Sam. 25:1; 28:3); the tomb traditionally seen as the burial spot of Samuel is still shown to visitors to the site. Several scholars have identified Nebi Samwil with the bama in Gibeon (1 Kg. 3:4), while others have recognized it as Be’eroth, one of the cities of the Gibeonites (Jos. 9:17). In the 1930s, Albright identified the site with biblical Mizpah, which he had previously associated with Tell

HISTORY

Numerous Iron Age remains dated to the eighth to sixth centuries BCE were found at the site. There are no remains dated to Iron Age I, the period of Samuel, which creates a problem as regards identification of Nebi Samwil with Mizpah. The site was destroyed by fire at the end of the First Temple period, following the assassination of Gedaliahu son of Ahikam. Abundant Persian and Hellenistic remains indicate the importance of the site during those periods. It was abandoned at the end of the Hellenistic period.

Settlement was renewed at Nebi Samwil only during the Byzantine period. Procopius, a Christian historian of the sixth century CE, recounts that Justinian surrounded the Monastery of Samuel with a wall and dug a cistern. The geographer Muqaddasi and the historian al-Yaqut both refer to the Monastery of St. Samuel at the site. This evidence coincides with the archaeological evidence, as jar handles bearing an Arabic inscription reading deir samwil (Monastery of Samuel) were found during excavations. In the Crusader period, the site was called Mons Gaudii. During his visit to the Holy Land (1106–1107), the Abbot Daniel states that Christians would dismount from their horses and make the sign of the cross upon viewing the Holy City. The church of Mons Gaudii is mentioned in documents of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher of 1157; historical sources relate that the king of Jerusalem granted 1,000 gold coins to the Cistercian order to construct a monastery and fortress there for pilgrims. In 1187, subsequent to the conquest of Jerusalem by

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE IRON AGE AND PERSIAN PERIOD. All of the finds from both the Iron Age and Persian period were found in fills in the southern Hellenistic quarter. There are no walls or structures unequivocally attributable to these two periods, as part of the site was cleared to bedrock during the Hellenistic period and again during the Byzantine and Crusader periods. Numerous pottery sherds of the eighth–seventh centuries BCE, including those bearing lamelekh and rosette seal impressions, were retrieved; as were engraved inscriptions and marks, and a scarab seal dated to the Egyptian Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. Persian period finds include ceramics, seal impressions of the yhd type, seal impressions depicting lions, and silver coins.

THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD. Uncovered on the southern slopes of the site was a residential quarter covering nearly 1 a. and dated to the Hellenistic period. It was very densely built and its structures were preserved to a height of 4.5 m, sometimes up to the third story. The quarter was transected by a street running east–west, 55 m long and 3.5 m wide. Beneath the street was a drainage channel built of large ashlars, its walls covered by a thick layer of plaster. Several multi-storied structures measuring 24 by 20 m inhabited the quarter, some constructed around a central courtyard. In some of the buildings the ground floor was occupied by stables. On the basis of the pottery and coins, this quarter appears to have been constructed at the beginning of the second century BCE and was abandoned in the second half of that century. Coins included issues of Ptolemy II, Antiochus IV, John Hyrcanus I, and Hyrcanus’ son Alexander Jannaeus, during whose reign the site was abandoned. There was a brief presence at the site during the period surrounding the destruction of the Second Temple.

THE BYZANTINE AND EARLY ISLAMIC PERIODS. On the basis of numismatic evidence, Nebi Samwil appears to have been resettled during the fourth century CE. In the fifth, the Monastery of St. Samuel was constructed there. The monastery was abandoned around the time of the Arab conquest; it is poorly preserved as a result of intensive Crusader period construction. During the Umayyad and early Abbasid periods, the site became a center for pottery production, specializing in the manufacture of storage jars. Four Umayyad period pottery kilns, each c. 2 m in diameter, were uncovered. Near the kilns were found numerous wasters, primarily storage jars, and handles with seal impressions in Arabic, among which are inscribed deir samwil and deir samwil yusuf. Jars produced at Nebi Samwil have been found at Caesarea, Ramla, and Jerusalem. They appear to have been utilized for the export of olive oil eastward.

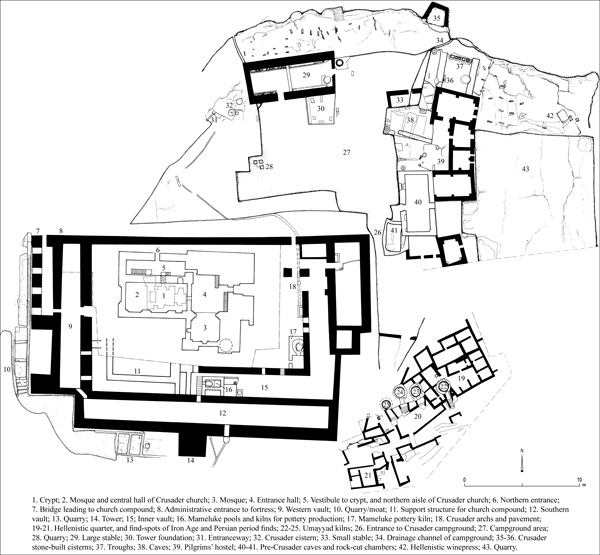

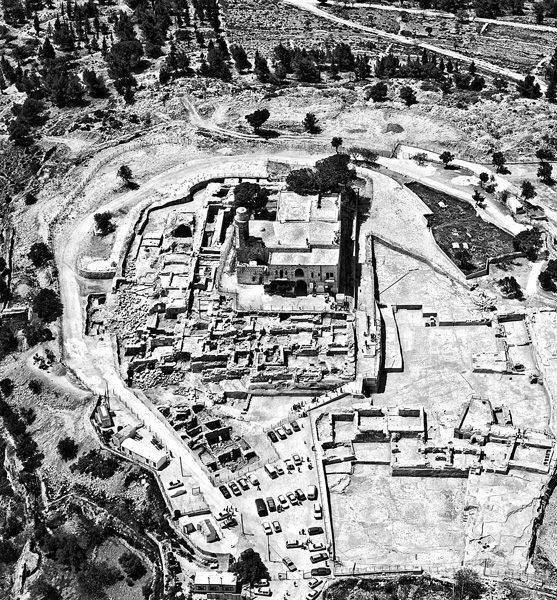

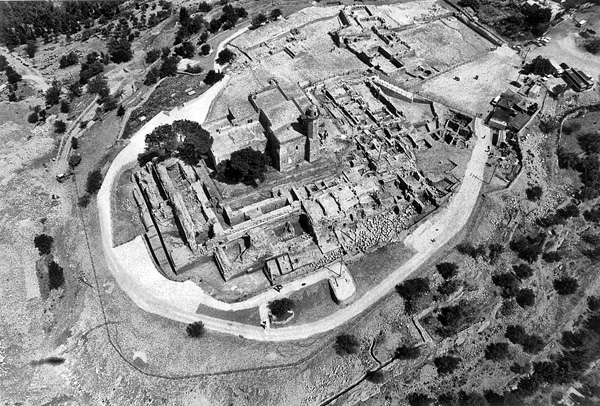

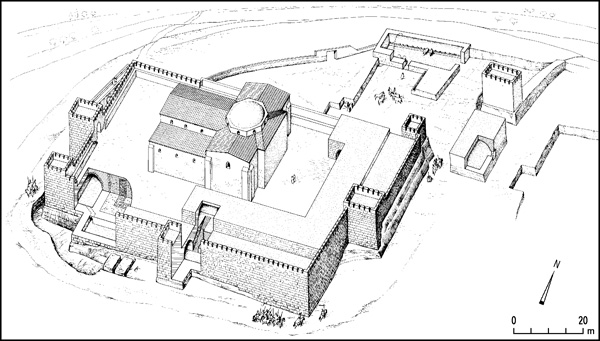

THE CRUSADER PERIOD. Jerusalem and numerous Crusader fortresses are visible from Nebi Samwil, which, as mentioned, controlled the main road from the Coastal Plain and Samaria to Jerusalem. The Crusader fortress built at the site is divided into several parts. At its center is a large church, which later became a mosque. A burial cave-crypt beneath the church is the traditional grave of the Prophet Samuel. Surrounding the church is a sturdy fortress surrounded by a moat. To the north are cisterns, stables, a tower, a pilgrims’ hostel, and large open spaces to accommodate pilgrims arriving to Jerusalem. A road rising towards the site from the west was apparently paved during the Crusader period.

The Crusader fortress is a rectangular structure, 100 by 67 m, on the southern flank of a dome-shaped hill. Massive retaining walls were constructed on the western and southern sides and barrel vaults were built to create a level, open area around the church. On the western and southern sides, a moat was started but never completed. Building materials were hewn on site and the quarries became an integral part of the fortress plan. The western wing measures 47 m in length and consists of a 42-by-10-m vault constructed on bedrock, which connects to the southern vault via a small postern. Its inner walls are of large ashlars. A 7-by-6-m tower stood in its southwestern corner, another in its northwestern, and a third—with a staircase—in its center. The entrance to the fortress was in the western wall; it consisted of a ramp built upon arches, some well-preserved. This north–south ramp is 28 m long and 2.6 m wide. The upper entrance to the fortress compound faced the entrance to the church. There was an additional entrance in the northern wall, leading to the rear of the church.

The southern wing, constructed of particularly large ashlars, rose to a height of c. 10 m. It was roofed by a single barrel vault, 72 m long and 8 m wide. Its external wall is c. 2 m thick, at its center a projecting tower, 6 by 6 m. A large segment of the eastern part of the southern wall collapsed in its entirety, its stones unearthed lying as they fell. This segment of the fortification appears to have been destroyed intentionally, perhaps by the soldiers of

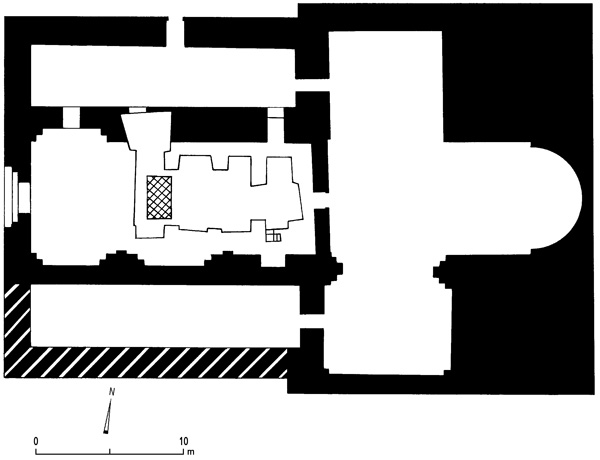

The Crusader church at the center of the site, its highest point, is the most prominent structure of Nebi Samwil. It measures 39 by 29 m and was built upon high man-made terraces. The church consisted of a central nave, functioning today as a mosque, and two aisles. Its tomb/crypt is a vaulted structure measuring 11.5 by 5 m, with two niches next to its western side. At the western end of the vault is the traditional tomb of the Prophet Samuel. While today one enters the crypt via openings in the northern aisle, in the Crusader period entrance was from the nave of the church, via a staircase into the southeastern corner of the cave. The southern aisle and apse of the church are not preserved. The bottom part of the main entrance of the church was found in the western wall of the nave; it was blocked during the Islamic period, when the entrance was moved from the western to the eastern side of the church.

On the northern side of the precinct was a large campground, entered from the south and measuring 47 by 37 m. Previous quarrying activity in this space left a high wall on its eastern side, eliminating the need to construct fortification walls there. Within the area were two large stables. The northern measures 27 by 11 m and was roofed with a barrel vault; preserved within it are rock-hewn food and water troughs and next to it was a large rock-cut cistern or well, and a square rock mass that appears to have been the base of a tower. On the eastern side was another stable, again with rock-hewn food and water troughs. A large vaulted structure, partly rock-cut and oriented north–south, stood on the southern side of the fortress; other structures were erected next to it, and to its north was a Crusader period cistern. The complex appears to have been a large pilgrims’ hostel. East of this area was another large quarry.

Northwest of the site is an abundant spring known as Ma‘ayan Shmu’el. From the natural cave where the spring is located, channels were cut to the spring outlet to increase the flow of water. East of the site is another spring known as Ma‘ayan

THE MAMELUKE PERIOD. During the Mameluke period, as in the Umayyad period, the abandoned fortress became once again a complex for the production of pottery vessels. Large kilns were constructed for the firing of pottery. Many fragments of wasters were found, as were materials used in pottery manufacture. The workshop relied on abundant water sources and raw materials found near the site. Soft limestone building stones were likely ground and utilized as temper. The widespread commercial activity at the site is evidenced by numerous coins.

After the Crusader period, the site became a place of Jewish prayer and pilgrimage. Its reputation as the burial site of Samuel spread following the withdrawal of the Crusaders. Travelers’ descriptions tell of the existence of a synagogue at the site. It is not known how the pottery factory and kilns co-existed with the Jewish holy site.

THE FINDS. Finds from the Iron Age until recent times include pottery, glassware, metal, and numerous coins. A shofar and a torah pointer bearing a Hebrew inscription date to the period in which the site was a Jewish holy place. Use of the site as a battlefield during World War I is attested to by hundreds of mortar shells, hand grenades, pistols, rifles, and bayonets.

YITZHAK MAGEN

INTRODUCTION

Nebi Samwil is located c. 7 km northwest of Jerusalem. It covers a total area of 5 a. and, at an elevation of 908 m, overlooks the main road from the Coastal Plain and western Samaria to Jerusalem. Its position has given it strategic importance since ancient times, and it has served as a military fortress and holy place for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Excavations were conducted at the site during the years 1992–2003 under the direction of Y. Magen, with the participation of M. Dadon, on behalf of the Staff Officer for Archaeology in Judea and Samaria.

IDENTIFICATION

The identification of the site of Nebi Samwil with biblical toponyms has been a matter of dispute. Medieval Jewish sources identified the site as Rama, the burial place of the Prophet Samuel (1 Sam. 25:1; 28:3); the tomb traditionally seen as the burial spot of Samuel is still shown to visitors to the site. Several scholars have identified Nebi Samwil with the bama in Gibeon (1 Kg. 3:4), while others have recognized it as Be’eroth, one of the cities of the Gibeonites (Jos. 9:17). In the 1930s, Albright identified the site with biblical Mizpah, which he had previously associated with Tell